Published online Aug 7, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i29.4836

Revised: June 4, 2013

Accepted: July 17, 2013

Published online: August 7, 2013

Idiopathic chronic ulcerative enteritis (ICUE) is a distinct entity without a defined etiology and is rarely seen in the clinic. Patients with ICUE mainly present with insidious abdominal symptoms such as chronic abdominal pain and intermittent gastrointestinal hemorrhage and symptoms of malnourishment in the early stages of the disease. ICUE is always difficult to diagnose. However, as the disease progresses, patients have a variety of acute abdominal complications such as hemorrhage, perforation, or ileus. Surgical intervention is always needed, and the condition can recur and require repeat laparotomy. When diffuse ulceration of the small bowel is present in the absence of recognizable causes, it is classified as nonspecific or idiopathic. The histological examination always demonstrates an acute, chronic inflammatory infiltration without giant cells, granulomas, or villous atrophy. The etiology of ICUE has not been identified, and its pathogenesis is poorly understood; therefore, radical surgical resection is considered the best available treatment. Here, we report a case of ICUE characterized by nonspecific, multiple, small intestinal ulcers resulting in perforation and recurrent bleeding. The differential diagnosis and the treatment are also discussed.

Core tip: This is a case report of idiopathic chronic ulcerative enteritis (ICUE) with perforation and recurrent bleeding. Complete clinical material of the patient is presented in this case report. We also provide several images, including colonoscopy, radiography, computed tomography, and pathology. All of this material reflected the clinical characteristics of ICUE. When patients present with multiple, nonspecific, small intestinal ulcers without a defined etiology, a diagnosis of ICUE should be considered. This case report will help diagnose and treat patients with similar clinical symptoms.

- Citation: Gao X, Wang ZJ. Idiopathic chronic ulcerative enteritis with perforation and recurrent bleeding: A case report. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(29): 4836-4840

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i29/4836.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i29.4836

Idiopathic chronic ulcerative enteritis (ICUE) is uncommon. It was first described by Nyman in 1949 as a kind of ulcerous jejunoileitis[1]. Since then, numerous descriptive terms have been used, including ulcerative jejunitis[2], chronic ulcerative jejunoileitis[3], nongranulomatous ulcerative jejunoileitis[4], and chronic nonspecific ulcerative duodenojejunoileitis[5]. These terms all attempt to describe a type of small bowel ulcerative disorder in the absence of a recognizable cause. Patients with ICUE present with hemorrhage, perforation, or obstruction and often need emergency surgical intervention. The pathogenesis of ICUE is not clear, and it is associated with a high mortality rate[6], therefore, surgical treatment remains a major challenge in clinical practice. Thus far, radical surgical resection is considered the best available treatment[7].

Here, we report a rare case of ICUE characterized by nonspecific, multiple, small intestinal ulcers resulting in perforation and recurrent bleeding, and discuss the differential diagnostic considerations and treatment.

A 78-year-old man was admitted to the hospital with intermittent dull pain in the upper quadrant of his abdomen of > 2 mo duration. The pain occurred irregularly and had no obvious relationship with meals. He reported experiencing nausea, vomiting, heartburn, diarrhea, melena, anorexia, fatigue, and weight loss of 12.5 kg. No hematemesis, hematochezia, tenesmus, or stools with mucus or pus were reported. The patient had a history of intestinal resection after trauma 10 years before. His mother had died of bladder cancer. Gastroscopy showed reflux esophagitis, duodenitis, and superficial gastritis throughout the stomach. No abnormality was noted on colonoscopy. On admission, his temperature (37 °C) and pulse (78 beats/min and regular) were normal. However, his blood pressure was a little lower than average (90/45 mmHg). Physical examination revealed tenderness in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen, without rebound tenderness or guarding. The bowel sounds were normal. Several enlarged lymph nodes could be palpated bilaterally in the neck and axilla. The lymph nodes were hard, stationary, and painless.

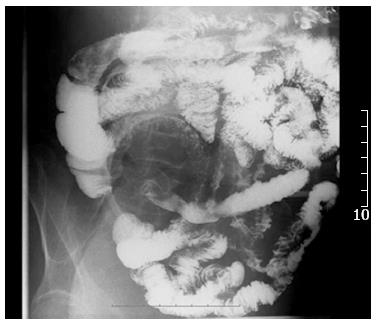

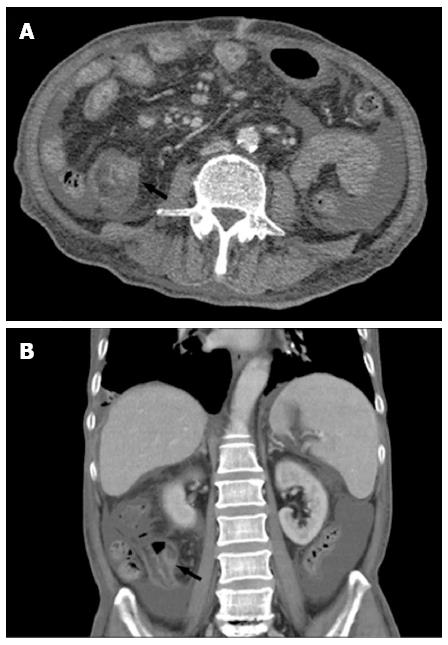

After admission, the patient had intermittent diarrhea, recurrent subxiphoid pain, abdominal distension, and anorexia. Screening for markers of viral hepatitis (A-E), cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, herpes simplex virus, and varicella zoster virus was negative. Stool cultures for the pathogens Shigella, Salmonella, Vibrio cholerae, Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Clostridium difficile (C. difficile), and C. difficile toxin A were negative. Stool culture was positive for intestinal Escherichia coli and enterococci, which accounted for 90% and 10% of normal intestinal flora, respectively. Multiple ulcers with a segmented pattern were noted in the terminal ileum on review of the colonoscopy (Figure 1). From the transverse to the sigmoid colon, the mucosa was rough and had erosive patches. The histopathology of biopsy specimens demonstrated acute and chronic nonspecific inflammation in the mucosa and submucosa, with a large quantity of plasma cell infiltration in the wall of the ileum, forming focal erosion and ulcers. The vasculature of the lamina propria was dilated and edematous. Radiographs of the whole digestive tract showed thickening of the terminal ileum mucosa, and peristalsis was poor (Figure 2), but the emptying function was normal. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) showed mild intestinal dilatation and wall thickening in the terminal ileum, and moderate ascites in the abdominal cavity (Figure 3). The mesenteric vasculature was normal, and the mesenteric lymph nodes were considered to have reactive hyperplasia. The proton pump inhibitor omeprazole was given to suppress acid production and protect the gastric mucosa, alleviating symptoms caused by the gastrointestinal tract ulceration. Meanwhile, the patient was given nutritional support to improve his nutritional status, probiotics to regulate intestinal flora, and an infusion of albumin combined with diuretic therapy to relieve edema. One month later, hemafecia occurred and worsened. Moreover, the patient’s general condition worsened, with anemia and hypoalbuminemia. On day 36 of hospitalization, his intermittent transient abdominal pain suddenly worsened. Symptoms of peritoneal irritation and severe distention of the entire abdomen emerged, with a rapid pulse and low blood pressure. The patient was diagnosed with diffuse peritonitis and septic shock. Emergency laparotomy and intraoperative endoscopy revealed multiple bleeding ulcers scattered in the ileum and perforation at the side of mesenteric margin. About 120 cm of the ileum had multiple bleeding ulcers, and the ulcerative perforation was resected. Although it had some superficial ulcers, the preserved proximal small intestine was not bleeding. Management was aimed at avoiding postoperative short bowel syndrome. The edematous small intestinal wall and poor nutritional status could have led to anastomotic leakage, therefore, a proximal and distal ileum double-lumen enterostomy was performed in the right lower quadrant of the abdomen.

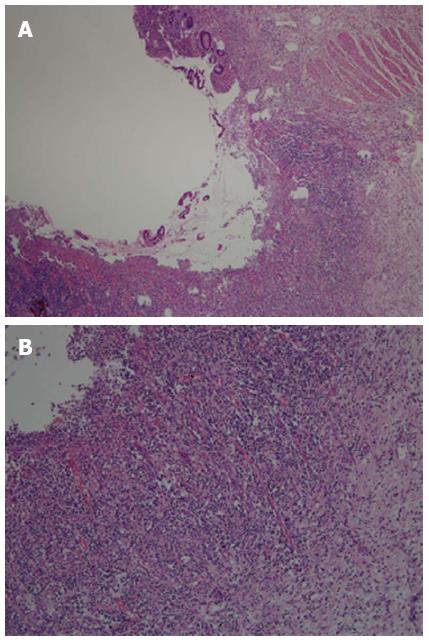

Gross pathological examination was performed after the intestinal specimen was cut longitudinally. The intestinal ulcers were round or oval with a diameter of 0.3-1.5 cm. In some ulcers, the long axis was parallel to the intestinal long axis (Figure 4). A perforated ulcer could be seen at the side of the mesenteric margin. The mesentery was thick and edematous, with enlarged mesenteric lymph nodes. Postoperative histological examination demonstrated partial intestinal villous atrophy and multiple nonspecific ulcers in the terminal ileum (Figure 5A). The examination also showed chronic inflammatory infiltration, with extensive small lymphocytes and plasma cells in the lamina propria, submucosa, and serosa (Figure 5B). The mesenteric lymph nodes had histiocytes, which contained lymphocytes and plasma cells in the dilated sinuses. Phagocytosis similar to that of Rosai-Dorfman disease was noted. After surgery, the patient’s vital signs were normal. However, on day 4, a large amount of bloody fluid began to leak from the ileal stoma. A blood transfusion and intravenous infusion did not alleviate symptoms of hemorrhagic shock. Bedside enteroscopy through the stoma showed multiple intestinal hemorrhages. Old and new ulcers were bleeding along 30 cm of the proximal intestine. Iced saline with norepinephrine and thrombin were used alternatively to irrigate the surface of the ulcers under enteroscopic guidance. The hemorrhage of the intestinal ulcers was controlled, but it recurred a few days later. Conservative treatment was continued. The patient’s general condition gradually deteriorated due to recurrent bleeding. Ultimately, the patient died of pneumonia and respiratory functional failure.

A variety of clinical conditions can lead to small intestinal ulcerations. Common causes include ischemia, trauma, nutritional disturbance, immune disorders, infection, drugs, and hormones. However, these causes can be easily excluded through medical history and laboratory test results. Therefore, most patients with small bowel ulcers have recognizable pathology. After a wide differential diagnosis, only those without an underlying disorder can be diagnosed as having ICUE.

The symptoms of small intestinal ulcers are nonspecific and insidious in the early stages. Patients with small intestinal ulcers usually present with chronic abdominal pain, diarrhea, a positive fecal occult blood test, intermittent hemafecia or melena, and a variety of types of malnutrition, including iron deficiency anemia, hypoalbuminemia, and weight loss. The diagnosis is often delayed or overlooked because the small intestine is the part of the alimentary canal most remote from both the mouth and the anus. Consequently, it is the most difficult to investigate. Patients typically experience exacerbations and complications such as intestinal hemorrhage, perforation, or obstruction, which always require emergency surgical intervention. With development of medical techniques such as gastrointestinal radiography, double-balloon enteroscopy[8], and capsule endoscopy[9], small intestinal ulcers can be diagnosed more accurately before surgery.

The patient complained chiefly of chronic abdominal pain for 2 mo, with many nonspecific gastrointestinal symptoms and increasing malnutrition. Later, symptoms of small intestinal ulcer bleeding and perforation emerged. We ruled out infective, ischemic, and tumor-related diseases. According to the laboratory results, we first excluded bacterial infection. With no history of atherosclerosis, hyperlipidemia, congestive heart failure, or arrhythmia, combined with normal findings on enhanced CT and ultrasonography of mesenteric vessels, we also ruled out mesenteric ischemia. Although the superficial and abdominal lymph nodes were enlarged, we obtained biopsy specimens from multiple sites during endoscopy and bone marrow biopsy and conducted a marrow chromosome examination to rule out lymphoma.

We needed to differentiate ICUE from diseases such as Crohn’s disease, Behcet’s disease, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID)-induced enteropathy, and cryptogenic multifocal ulcerous stenosing enteritis (CMUSE) because they also may cause multiple small intestinal ulcers.

During surgery, we found that the multiple intestinal ulcers mainly diffused in the terminal ileum. The ulcers were sharply demarcated with a round or oval shape, and the intervening mucosa was normal. The diameter of the ulcers ranged from 0.3 to 1.5 cm, with varying depths. The superficial ulcers were limited to mucosa or submucosa, while the deep ones can reach the serosa and even form a transmural perforation. The lesions were different from those seen in Crohn’s disease, which are generally longitudinal, with a cobblestone appearance and fistulas.

ICUE can also be differentiated to the intestinal involvement of Behcet’s disease. In Behcet’s disease, ulcers are usually found from terminal ileum to the cecum, with transmural inflammation extending to the serous membrane and crater-shaped ulcer margins. In addition, Behcet’s disease usually has a triad of symptoms consisting of aphthous stomatitis, genital ulcers, and ocular symptoms, which this patient did not have.

Since 1960, it has been recognized that NSAIDs can cause small intestinal ulcers. The macroscopic lesions of NSAID-induced enteropathy are characterized by multiple circumferential ulcers with severe concentric stenosis, referred to as “diaphragm disease”[10]. The different pathological characteristics in the patient and no history of NSAID use excluded NSAID-induced enteropathy.

CMUSE also can cause nonspecific multiple intestinal ulcers. Perlemuter et al[11] summarized the clinicopathological features of CMUSE as unexplained small intestinal strictures, superficial ulceration of the mucosa and submucosa, no biological signs of systemic inflammatory reaction, a chronic or recurrent clinical course even after surgery, and a positive response to use of corticosteroids. For our patient, the syndrome was characterized by recurrent intestinal bleeding and perforation, ulcers that were not limited to the submucosa, and no ulcerative stenosis or obstruction. Therefore, we excluded the diagnosis of CMUSE.

The etiology of ICUE is unknown, and symptoms of the disease are nonspecific and insidious. In the early stages, patients usually present with chronic abdominal pain and symptoms of malabsorption that do not respond to conservative treatments such as a gluten-free diet or adrenocorticosteroids. The clinical course could be severe and rapidly fatal due to complications such as hemorrhage, perforation, sepsis, and cachexia[12]. Surgical treatment is always required, after which the condition may recur and require repeat laparotomy. In many reports, ICUE was diagnosed after several operations and exclusion of other underlying disorders. The diagnosis was confirmed by histological features characterized by the diffuse nongranulomatous ulcerations called multiple nonspecific small intestinal ulcers. Some patients survive after radical, aggressive surgical resection[7]. In the present case, considering the advanced age and poor nutritional status of the patient and the risk of short bowel syndrome, part of the affected segment was preserved. Nevertheless, the conserved superficial ulcers deteriorated, and multiple new ulcers emerged; both were bleeding after surgery. Corticosteroid therapy is not effective in ICUE[13], and it is never used in patients with gastrointestinal hemorrhage, therefore, we avoided corticosteroid therapy. The ulcers were deep and transmural, thus, we believed that multiple intestinal perforations would emerge as the disease progressed. Postoperative aggravation of the ulcerative injury in the small intestine precluded reoperation and led to patient’s debility and death.

In conclusion, early diagnosis and treatment are important in ICUE. Radical surgical resection is considered the best available treatment for patients presenting with abdominal ulcerative complications such as hemorrhage, perforation, and obstruction, although the true etiology of ICUE is unknown. When patients present with multiple, nonspecific, small intestinal ulcers in the absence of well-documented causes, a diagnosis of ICUE should be considered. However, patients of advanced age with compromised nutritional status and severe complications cannot undergo aggressive surgery. In these patients, the prognosis is usually guarded.

P- Reviewer Loffroy R S- Editor Wen LL L- Editor A E- Editor Zhang DN

| 1. | Nyman E. Ulcerous jejuno-ileitis with symptomatic sprue. Acta Med Scand. 1949;134:275-283. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 22] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Goulston KJ, Skyring AP, Mcgovern VJ. Ulcerative jejunitis associated with malabsorption. Australas Ann Med. 1965;14:57-64. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Karz S, Guth PH, Polonsky L. Chronic ulcerative jejunoileitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1971;56:61-67. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Corlin RF, Pops MA. Nongranulomatous ulcerative jejunoileitis with hypogammaglobulinemia. Clinical remission after treatment with -globulin. Gastroenterology. 1972;62:473-478. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Modigliani R, Poitras P, Galian A, Messing B, Guyet-Rousset P, Libeskind M, Piel-Desruisseaux JL, Rambaud JC. Chronic non-specific ulcerative duodenojejunoileitis: report of four cases. Gut. 1979;20:318-328. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 21] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Boydstun JS, Gaffey TA, Bartholomew LG. Clinicopathologic study of nonspecific ulcers of the small intestine. Dig Dis Sci. 1981;26:911-916. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 37] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Sutton CD, White SA, Marshall LJ, Dennison AR, Thomas WM. Idiopathic chronic ulcerative enteritis--the role of radical surgical resection. Dig Surg. 2002;19:406-408. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Zhi FC, Yue H, Jiang B, Xu ZM, Bai Y, Xiao B, Zhou DY. Diagnostic value of double balloon enteroscopy for small-intestinal disease: experience from China. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:S19-S21. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 24] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Chen Y, Ma WQ, Chen JM, Cai JT. Multiple chronic non-specific ulcer of small intestine characterized by anemia and hypoalbuminemia. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:782-784. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 4] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lang J, Price AB, Levi AJ, Burke M, Gumpel JM, Bjarnason I. Diaphragm disease: pathology of disease of the small intestine induced by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. J Clin Pathol. 1988;41:516-526. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 230] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 210] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Perlemuter G, Guillevin L, Legman P, Weiss L, Couturier D, Chaussade S. Cryptogenetic multifocal ulcerous stenosing enteritis: an atypical type of vasculitis or a disease mimicking vasculitis. Gut. 2001;48:333-338. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 70] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lawrason FD, Alpert E, Mohr FL, Mcmahon FG. Ulcerative-obstructive lesions of the small intestine. JAMA. 1965;191:641-644. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 67] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Karnam US, Rosen CM, Raskin JB. Small Bowel Ulcers. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2001;4:15-21. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 10] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |