Published online May 14, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i18.2835

Revised: March 11, 2013

Accepted: March 13, 2013

Published online: May 14, 2013

Two cases of gastroendoscopy-associated Acinetobacter baumannii (A. baumannii) bacteremia were discovered at the study hospital. The first case was a 66-year-old woman who underwent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and endoscopic retrograde papillotomy, and then A. baumannii bacteremia occurred. The second case was a 70-year-old female who underwent endoscopic retrograde biliary drainage due to obstruction of intra-hepatic ducts, and bacteremia occurred due to polymicrobes (Escherichia coli, viridans streptococcus, and A. baumannii). After a literature review, we suggest that correct gastroendoscopy technique and skill in drainage procedures, as well as antibiotic prophylaxis, are of paramount importance in minimizing the risk of gastroendoscopy-associated bacteremia.

Core tip: After a literature review, we suggest that correct gastroendoscopy technique and skill in drainage procedures, as well as antibiotic prophylaxis, are of paramount importance in minimizing the risk of gastroendoscopy-associated bacteremia. Gastroenterologists should give more attention to gastroendoscopy-related infections, and increased clinical alertness may be the best way to reduce the impact from these types of infections.

-

Citation: Chen CH, Wu SS, Huang CC. Two case reports of gastroendoscopy-associated

Acinetobacter baumannii bacteremia. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(18): 2835-2840 - URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i18/2835.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i18.2835

Gastroendoscopy is a commonly used procedure for diagnosis and therapy, such as in endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). Infection is one of the most common morbidity complications of gastroendoscopy. Septic complications of ERCP include ascending cholangitis, liver abscess, acute cholecystitis, infected pancreatic pseudocyst, infection following perforation of a viscus, and, less commonly, endocarditis and endovasculitis[1]. Bacteria can enter the biliary tract by hematogenous or, more frequently, by a retrograde route, and the most common organisms transmitted by ERCP are Escherichia coli, Klebsiella species, and Enterobacter species[2]. Here we report two interesting cases of gastroendoscopy-associated Acinetobacter baumannii (A. baumannii)(GEaAb) bacteremia.

The patient was a 66-year-old woman who visited a gastroenterologist for complaints of right upper quadrant pain and hunger pain. The initial impression was of a gall bladder stone. An ERCP was performed, and it showed a common bile duct of 16.1 mm in diameter and several filling defects in the gall bladder; therefore, an endoscopic retrograde papillotomy (EPT) was executed over the proximal portion of the bile duct, after which a gallstone was removed. The course of the procedure went smoothly. She again began to feel right quadrant pain and fever the next day, so she was admitted for further evaluation and management. At admission, vital sign measurements were: blood pressure, 100/90 mmHg; temperature, 38 °C; pulse rate, 110 beats/min; and respiratory rate, 20 breaths/min. The patient appeared acutely ill. The abdomen was distended and ovoid. There was radiation pain and tenderness to her back, and abdominal fullness over the right quadrant area (positive Murphy’s sign), but no rebounding pain. Admission laboratory results revealed the following: white blood cell count, 12700/mm3; blood creatinine level, 0.8 mg/dL; serum amylase, 815 IU/L; serum bilirubin, 0.88 mg/dL; aspartate transaminase, 55 U/L; and alanine transaminase, 140 U/L. Abdominal echography revealed peri-pancreatic fluid accumulation. On the first day of admission, the patient was treated with antibiotics (cefazolin 1 g every 8 h plus gentamicin 60 mg every 12 h) and adequate fluid hydration, after initially remaining nil per os (NPO). A blood culture revealed A. baumannii on the 4th admission day, and the antibiotic treatment was switched to imipenem-cilastatin 500 mg every 6 h according to the antibiotics susceptibility test. Clinically, the source of A. baumannii was from the biliary tract, and it could be related to the previous invasive procedure. Because of persistent fever, an abdominal computed tomography was performed and showed a pancreatic abscess; consequently, an echo-guided aspiration was performed on the 5th admission day. The fever gradually subsided and follow-up laboratory data showed improvement. The total duration of parenteral imipenem-cilastatin usage was 21 d, after which antibiotic therapy was switched to oral levofloxacin 500 mg per os daily. The patient was discharged on the 44th admission day and was followed in the out-patient department (OPD). She has recovered quite well.

This patient was a 70-year-old female with liver cirrhosis related to hepatitis C virus infection. At initial presentation, laboratory test results were as follows: serum bilirubin, 0.52 mg/dL; aspartate transaminase, 42 U/L; alfa-fetoprotein, < 20 ng/mL; and hepatitis C virus-antibody titer, positive. The abdominal computed tomography scan showed multiple nodular hypervascular tumor stains in both lobes of the liver, especially in the right lobe. Hepatocellular carcinoma was highly suspected. Transarterial chemo-embolization (TACE) of both sides of the liver was performed, and she was regularly followed in the OPD while she received TACE 6 times over the course of 20 mo. Her follow-up laboratory tests showed a serum bilirubin of 8.6 mg/dL, an aspartate transaminase of 72 U/L, and an alkaline phosphatase of 371 U/L. An abdominal echography exam revealed focal dilated intra-hepatic ducts. Hence, an endoscopic retrograde biliary drainage (ERBD) procedure was performed accordingly, at which time a stent (11 Fr) was inserted into the intra-hepatic ducts through the common bile duct. She began to feel right quadrant pain and fever three days later, and she was admitted under the impression of cholangitis. At admission, vital signs included a blood pressure of 100/90 mmHg, a temperature of 38 °C, a pulse rate of 110 beats/min, and a respiratory rate of 20 breaths/min. Murphy’s sign was positive. Admission laboratory results revealed the following: white blood cell, 5600/mm3; serum total bilirubin, 27.65 mg/dL; serum direct bilirubin, 19.2 mg/dL; aspartate transaminase, 60 U/L; and alanine transaminase, 140 U/L. The abdominal echography showed left intra-hepatic duct dilatation. On the first day of admission, the patient was treated with antibiotics (cefazolin 1 g every 8 h plus gentamicin 60 mg every 12 h) and adequate fluid hydration after initially being NPO. Echo-guided percutaneous transhepatic cholangeal drainage was performed. Blood culture revealed polymicrobes (Escherichia coli, viridans streptococcus, and A. baumannii) on the 4th admission day, and treatment was changed to imipenem-cilastatin 500 mg every 6 h according to the antibiotics susceptibility test. The fever gradually subsided. Clinically, the source of A. baumannii was from the biliary tract, and it could be related to the previous invasive procedure. Follow-up laboratory data did not, however, seem much improved. This patient expired due to severe hepatic failure with multiple organ failure.

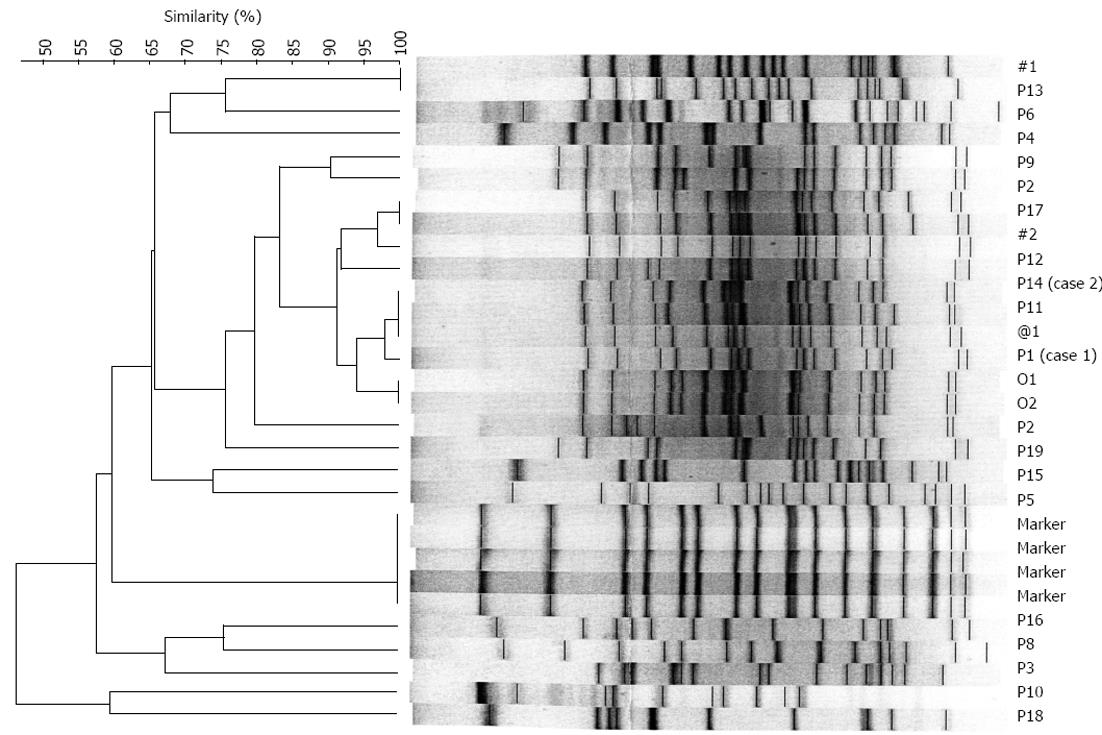

After noting those two GEaAb cases in our institute, we conducted an evidence-based literature review (Table 1)[3-7]. Norfleet’s study showed that 6% of patients who received upper gastrointestinal endoscopic examinations developed bacteremia, but only one of 447 patients acquired Acinetobacter bacteremia[4]. Maulaz’s study described that the bacteremia incidence in cirrhotic patients who received variceal ligation was 2.5%, and only one Acinetobacter lwoffii infection was disclosed[5]. Only two case reports described post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography-associated Acinetobacter infection in the United States National Library of Medicine National Institutes of Health[6,7]. Additionally, we performed a retrospective cross-sectional epidemiological study in our institute to identify GEaAb bacteremia cases and elucidate the possible sources of infection for a further five years from the year of identifying these two patients. During this period of five years, we disclosed 45 A. baumannii bacteremia cases. Most of them resulted from hospital-acquired pulmonary infection. We focused on biliary tract infections and gastroendoscopy-associated A. baumannii, but neither a case of biliary tract infection nor a case of GEaAb were disclosed among hospital-acquired infection patients. So, we excluded those hospital-acquired A. baumannii patients, and the results were 19 patients with documented non-hospital-acquired A. baumannii bacteremia. We focused on these 19 patients (the demographics and clinical presentations are listed in Table 2). We also performed a pulse-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) analysis according to Seifert’s method[8], and the results are shown in Figure 1. Patients 1, 11 and 14 appeared to have had similar fingerprint patterns according to a dendrogram and PFGE (Figure 1). In the analysis of 5 biliary sepsis cases, risk factors included one patient with common bile duct stone, one with diabetes mellitus, one with cholangiocarcinoma, one with liver cirrhosis, and one with hepatocellular carcinoma. In addition, 3 patients had received invasive diagnostic or therapeutic procedures: one had an EPT, one underwent percutaneous transhepatic cholangeal drainage, and one had ERBD (Table 2). Two of 5 biliary sepsis cases developed A. baumannii bacteremia. All of those patients received prophylactic antibiotics before the invasive medical procedures.

| Ref. | Country | Evaluation | Risk factors | Microbiology | Treatment | Outcome |

| Norfleet et al[3], 1981 | United States | 447 patients have been evaluated, of which 6% had bacteremia after upper gastrointestinal endoscopy | Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy | One case with Acinetobacter sp infection | NM | NM |

| Maulaz et al[4], 2003 | Brazil | The bacteremia incidence in cirrhotic patients submitted to variceal ligation was 2.5%, showing no difference from the control groups | Endoscopic variceal ligation or esophagogastroduodenoscopy only | One case with Acinetobacter lwoffii infection | NM | One case with Acinetobacter lwoffii infection is survived |

| Oh et al[5], 2007 | South Korea | A total of 364 patients who underwent PTC were included in the study | Cholangitis and bacteremia were associated with percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage and tract dilation, catheter migration and blockage with tract maturation, and bile duct injury with PTC | NM | NM | NM |

| Lai et al[6], 2008 | Taiwan | Case report | Endoscopic procedure | Initial, polymicrobes (Acinetobacter baumannii, Klebsiella pneumoniae and Enterococcus Faecalis), then became Acinetobacter genomic species 13TU at day 14 | Ceftazidime and ampicillin-sulbactam, then intravenous gentamicin and ciprofloxacin (parenteral antibiotics for 4 wk) then followed by oral ciprofloxacin and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (for another 13 d) , antibiotics used for 61 d in total | Survived |

| de la Tabla Ducasse et al[7], 2008 | Spain | Case report | Post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography | Acinetobacter ursingii infection | Cefotaxime | Survived |

| No. | Age (yr) | Sex | Chief complaint (d) | Previous admission | Initial diagnosis of infection | Underlying disease | Fever/shock | Route of entry1 | Treatment (d) | Outcome |

| P1 | 67 | F | RUQ pain (1) | 0 | Pancreatic abscess | CBD stone | Y/N | Biliary tract1 | Cefazoline+gentamicin (5), imipenem-cilastatin (12), levofloxacin (8) | S |

| P2 | 76 | F | Conscious disturbance (3) | 3 | Liver abscess | DM | Y/N | Biliary tract | Cefmetazole (3), imipenem-cilastatin (7), levofloxacin (7) | S |

| P3 | 79 | M | SOB (7) | 3 | Pneumonia | Esophageal cancer | Y/N | Respiratory tract | Co-trimoxazole (4) | S |

| P4 | 40 | F | SOB (3) | 2 | Sepsis | Breast cancer | Y/N | Primary2 | Cefazoline+gentamicin (5), levofloxacin (7) | S |

| P5 | 74 | M | Deafness (4) | 0 | Sepsis, sudden deafness | Nil | Y/N | Primary | Cefazoline + gentamicin (1) | S |

| P6 | 24 | F | Fever, right flank pain (1) | 2 | Acute pyelonephritis | Pelvic cancer | Y/N | Urinary tract | ampicillin-sulbactam (7), co-trimoxazole (3) | S |

| P7 | 76 | F | Chest pain (1) | 0 | Sepsis | AMI | N/Y | Primary | Cefmetazole (4), imipenem-cilastatin (7) | S |

| P8 | 80 | F | SOB (1) | 1 | Urinary tract infection | Right renal stone | Y/N | Urinary tract | Cefazoline (5), amikacin (7) | S |

| P9 | 82 | M | Hematuria (1) | 1 | Urinary tract infection | Old CVA | Y/N | Urinary tract | Nil | S |

| P10 | 1 | M | Fever (1) | 0 | Neonetal infection | Nil | Y/N | Primary | Ampicillin (5) | S |

| P11 | 33 | F | SOB (3) | 1 | Sepsis | Cholangiocarcinoma | Y/N | Primary3 | Cefmetazole (1), imipenem-cilastatin (7) | S |

| P12 | 64 | M | Abdominal pain (3) | 2 | Cholangitis | Liver cirrhosis, uremia, AF | N/Y | Biliary tract | Cefazoline (5), gentamicin (14) | E |

| P13 | 73 | F | Epigastric pain (1) | 0 | Urosepsis | DM | Y/N | Urinary tract | Imipenem-cilastatin (14) | S |

| P14 | 70 | M | RUQ pain (1) | 2 | Cholangitis | HCC, HCV | N/N | Biliary tract4 | Cefamet (5), imipenem-cilastatin (9) | E |

| P15 | 79 | M | Loss of consciousness (1) | 1 | Sepsis | DM | N/N | Primary | Cefazoline (7) | S |

| P16 | 79 | F | Fever (1) | 4 | Lung abscess | DKA | Y/Y | Respiratory tract | Cefuroxime (2) | E |

| P17 | 80 | M | Dysuria (7) | 1 | Urinary tract infection | DM, urethral stricture HBV | Y/N | Urinary tract | imipenem-cilastatin (14) | S |

| P18 | 51 | F | Right limb weakness (2) | 4 | Pneumonia | Chf | N/N | Respiratory tract | Cefazoline (7), co-trimoxazole (7) | S |

| P19 | 80 | F | Hematuria (3) | 1 | Urinary tract infection | Left hydronephrosis, right urethral stone | N/N | Urinary tract | Cefazoline (3), urotactin (11) | S |

This is the first serial study and case reports of GEaAb bacteremia in Taiwan. In our study, this infection was seen in one patient after an EPT, and in one patient who underwent ERBD. Both diagnostic and therapeutic gastroendoscopy can lead to bacteremia, and gastroendoscopy-associated infection rates up to 27% have been associated with therapeutic procedures[9-11].

Concerning the mechanisms of gastroendoscopy-associated infections, bacteria can enter the biliary tract by a hematogenous or, more frequently, a retrograde route. Estimates of the incidence of clinically significant cholangitis have ranged from 0.4% to more than 10% (mean, 1.4%), depending upon the study population[12]. Entrance into the blood stream is presumably through minor trauma by the endoscope[13]. Another factor influencing the rate of cholangitis is the use of prophylactic antibiotics[14]. Results from these studies were similar to the results in our study.

The most frequent organisms responsible for cholangitis and biliary sepsis are enteric bacteria, such as Escherichia coli, Klebsiella species, and Enterobacter species[2]. A. baumannii, which was reported in this study, is rare, so we performed a molecular epidemiological study. Patients 1, 11 and 14 appeared to have had similar fingerprint patterns according to a dendrogram and PFGE (Figure 1), and those 3 patients had experienced invasive gastrointestinal endoscopic procedures. Although we suspect the relationship, we still cannot prove the causal association between the procedure and infection in this study. We lacked direct microbiological evidence as well as estimates of the infection rate in the gastroendoscopy room. Also, there was no significant evidence of endemic A. baumannii infection at Changhua County.

In conclusion, we believe that accurate gastroendoscopy techniques and skill in drainage procedures are of paramount importance for minimizing the risk of GEaAb bacteremia. Antibiotic prophylaxis is also widely considered to be indicated in selected patients. Gastroenterologists should give more attention to gastroendoscopy-related infections, and increased clinical alertness may be the best way to reduce the impact from these types of infections.

The authors thank Changhua Christian Hospital for the kind gift of the clinical A. baumannii strains. The authors thank the Gastroendoscopy Room of Changhua Christian Hospital for surveillance cooperation. The authors thank Choiu CS and Laiu JC of the Central Branch Office, Center for Disease Control, Taichung for the PFGE assistance.

P- Reviewer Lindén S S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor Logan S E- Editor Li JY

| 1. | Subhani JM, Kibbler C, Dooley JS. Review article: antibiotic prophylaxis for endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13:103-116. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 41] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lin GM, Lin JC, Chen PJ, Siu LK, Huang LY, Chang FY. Pan-drug resistant Acinetobacter baumannii bacteremia following endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:498-499. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Norfleet RG, Mitchell PD, Mulholland DD, Philo J. Does bacteremia follow upper gastrointestinal endoscopy? Am J Gastroenterol. 1981;76:420-422. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Maulaz EB, de Mattos AA, Pereira-Lima J, Dietz J. Bacteremia in cirrhotic patients submitted to endoscopic band ligation of esophageal varices. Arq Gastroenterol. 2003;40:166-172. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 11] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Oh HC, Lee SK, Lee TY, Kwon S, Lee SS, Seo DW, Kim MH. Analysis of percutaneous transhepatic cholangioscopy-related complications and the risk factors for those complications. Endoscopy. 2007;39:731-736. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 111] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lai YH, Chen TL, Chen CP, Tsai CC. Nosocomial acinetobacter genomic species 13 TU endocarditis following an endoscopic procedure. Intern Med. 2008;47:799-802. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 17] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | de la Tabla Ducasse VO, González CM, Sáez-Nieto JA, Gutiérrez F. First case of post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography bacteraemia caused by Acinetobacter ursingii in a patient with choledocholithiasis and cholangitis. J Med Microbiol. 2008;57:1170-1171. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Seifert H, Schulze A, Baginski R, Pulverer G. Comparison of four different methods for epidemiologic typing of Acinetobacter baumannii. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1816-1819. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | Kullman E, Borch K, Lindström E, Anséhn S, Ihse I, Anderberg B. Bacteremia following diagnostic and therapeutic ERCP. Gastrointest Endosc. 1992;38:444-449. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 46] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Sauter G, Grabein B, Huber G, Mannes GA, Ruckdeschel G, Sauerbruch T. Antibiotic prophylaxis of infectious complications with endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. A randomized controlled study. Endoscopy. 1990;22:164-167. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 67] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Niederau C, Pohlmann U, Lübke H, Thomas L. Prophylactic antibiotic treatment in therapeutic or complicated diagnostic ERCP: results of a randomized controlled clinical study. Gastrointest Endosc. 1994;40:533-537. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 63] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Barthet M, Lesavre N, Desjeux A, Gasmi M, Berthezene P, Berdah S, Viviand X, Grimaud JC. Complications of endoscopic sphincterotomy: results from a single tertiary referral center. Endoscopy. 2002;34:991-997. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 95] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Mani V, Cartwright K, Dooley J, Swarbrick E, Fairclough P, Oakley C. Antibiotic prophylaxis in gastrointestinal endoscopy: a report by a Working Party for the British Society of Gastroenterology Endoscopy Committee. Endoscopy. 1997;29:114-119. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 35] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Loperfido S, Angelini G, Benedetti G, Chilovi F, Costan F, De Berardinis F, De Bernardin M, Ederle A, Fina P, Fratton A. Major early complications from diagnostic and therapeutic ERCP: a prospective multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;48:1-10. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 801] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 746] [Article Influence: 28.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |