Published online Aug 21, 2012. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i31.4228

Revised: April 17, 2012

Accepted: April 20, 2012

Published online: August 21, 2012

We present three cases of autoimmune pancreatitis (AIP) complicated by gastric varices. Case 1: A 57-year-old man was diagnosed with AIP complicated by gastric varices and splenic vein obstruction. Splenomegaly was not detected at the time of the diagnosis. The AIP improved using steroid therapy, the splenic vein was reperfused, and the gastric varices disappeared; case 2: A 55-year-old man was diagnosed with AIP complicated by gastric varices, splenic vein obstruction, and splenomegaly. Although the AIP improved using steroid therapy, the gastric varices and splenic vein obstruction did not resolve; case 3: A 68-year-old man was diagnosed with AIP complicated by gastric varices, splenic vein obstruction, and splenomegaly. The gastric varices, splenic vein obstruction, and AIP did not improve using steroid therapy. These three cases suggest that gastric varices or splenic vein obstruction without splenomegaly may be an indication for steroid therapy in patients with AIP because the complications will likely become irreversible over time.

- Citation: Goto N, Mimura J, Itani T, Hayashi M, Shimada Y, Matsumori T. Autoimmune pancreatitis complicated by gastric varices: A report of 3 cases. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18(31): 4228-4232

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v18/i31/4228.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v18.i31.4228

Autoimmune pancreatitis (AIP) is accepted worldwide as a distinctive type of pancreatitis, and the number of patients with AIP is increasing[1-5]. However, there are few reports of AIP complicated by gastric varices, and the effect of steroid therapy on the gastric varices is unknown. We present three cases of autoimmune pancreatitis complicated by gastric varices.

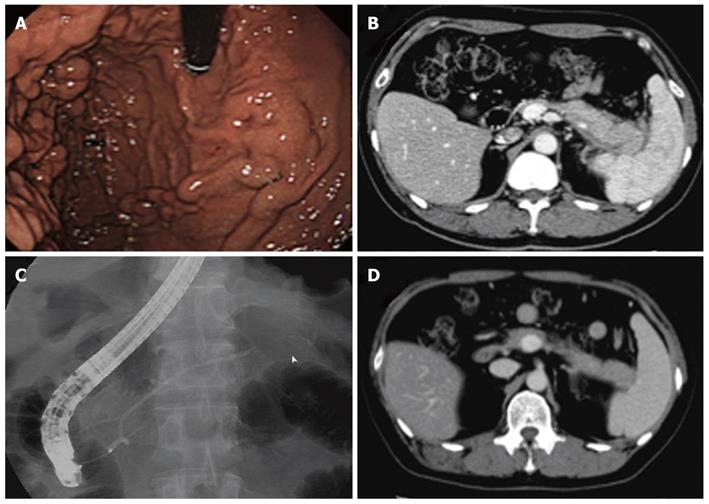

A 57-year-old man was admitted to the hospital due to back pain and jaundice. He had a history of diabetes mellitus and no history of habitual alcohol consumption. Laboratory studies revealed liver dysfunction (total bilirubin 3.1 mg/dL, aspartate aminotransferase 275 IU/L, alanine aminotransferase 557 IU/L, and alkaline phosphatase 2822 IU/L), hyperglycemia (236 mg/dL), elevated hemoglobin A1c (7.9%), and elevated IgG4 (176.4 mg/dL). Tumor markers, a complete blood count, electrolyte plasma levels, coagulation tests, amylase levels, lipase levels, and kidney function were all within the normal limits. Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen revealed a diffusely enlarged pancreas with a capsule-like rim, an obstructed splenic vein, and a dilated common bile duct (Figure 1A). Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) revealed irregular narrowing of the main pancreatic duct and stricture of the lower common bile duct. Esophagogastoroduodenoscopy (EGD) revealed gastric varices in the fundus of the stomach (Figure 1B).

According to the 2006 Clinical Diagnostic Criteria of The Japan Pancreas Society, the patient was diagnosed with AIP complicated by splenic vein obstruction and gastric varices. Endoscopic biliary drainage by stent placement was performed to alleviate the obstructive jaundice, followed by the oral administration of 30 mg/d prednisolone for 2 wk. The dose was tapered by 5 mg every 2 wk to a maintenance dose of 5 mg/d. Two weeks after the initial treatment, a CT scan showed that the enlarged pancreas had improved and that the splenic vein was reperfused (Figure 1C). Six mo after the initial therapy, EGD showed that the gastric varices had disappeared (Figure 1D). Twenty-one mo after admission to the hospital, the patient was followed in the clinic with a maintenance dose of 5 mg/d prednisolone.

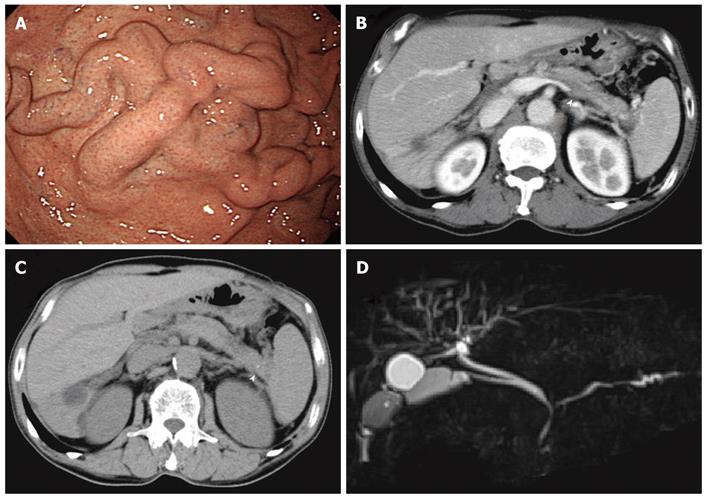

A 55-year-old man was admitted to the hospital following the incidental detection of gastric fundal varices on EGD during a complete physical examination (Figure 2A). He had no previous illnesses and no history of habitual alcohol consumption. The patient was asymptomatic, and nothing abnormal was detected on physical examination. A CT scan revealed a locally enlarged pancreatic tail with a capsule-like rim around the lesion, an obstructed splenic vein, and splenomegaly (Figure 2B). ERCP was performed, revealing irregular narrowing of the main pancreatic duct in the pancreatic tail (Figure 2C). Laboratory studies showed an elevated IgG4 (239.1 mg/dL). Tumor markers, a complete blood count, electrolyte plasma levels, coagulation tests, amylase levels, lipase levels, and kidney and liver functions were all within the normal limits.

According to the 2006 Clinical Diagnostic Criteria, the patient was diagnosed with AIP complicated by splenic vein obstruction, gastric varices, and splenomegaly. Oral administration of 30 mg/d prednisolone for 4 wk was used to induce remission, and the dose was tapered by 5 mg every 2 wk to a maintenance dose of 5 mg/d. Two weeks after the initial treatment, a CT scan showed that the enlarged pancreas tail had improved and that the capsule-like rim had disappeared (Figure 2D). However, the splenic vein was not reperfused. Ten mo after the initial therapy, EGD showed no improvement of the gastric varices. One year after hospital admission, the patient was followed in the clinic with a maintenance dose of 5 mg/d prednisolone.

A 68-year-old man was admitted to the hospital due to hematemesis. An emergency EGD was performed, revealing gastric ulcer bleeding at the gastric notch and incidentally detected gastric varices in the fundus of the stomach (Figure 3A). The gastric ulcer was successfully treated with endoscopic coagulation and administration of a proton pump inhibitor. Additional investigations were performed to ascertain the cause of the gastric varices. The patient had a past history of diabetes mellitus and no history of habitual alcohol consumption. A CT scan revealed a slightly enlarged pancreas with a capsule-like rim around the lesion, a pancreatic stone in the pancreatic tail, an obstructed splenic vein, and splenomegaly (Figure 3B and C). Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) revealed irregular narrowing of the main pancreatic duct in the pancreatic head and body, slight dilation of the main pancreatic duct in the pancreatic tail, stricture of the hilar bile duct and lower bile duct, and dilation of the right intra-hepatic bile duct (Figure 3D). ERCP showed the same findings as MRCP. Laboratory studies revealed elevated levels of IgG4 (186 mg/dL), hemoglobin A1c (8.0%), carcinoembryonic antigen (8.2 ng/mL), CA19-9 (38.7 U/mL), and alkaline phosphatase (345 IU/L). The complete blood count, electrolyte plasma levels, coagulation tests, amylase levels, lipase levels, and kidney function were all within the normal limits.

Although the slight dilation of the distal main pancreatic duct was atypical of AIP, the slightly enlarged pancreas, the irregular narrowing of the main pancreatic duct in the pancreatic head and body, and the elevated levels of IgG4 met the 2006 Clinical Diagnostic Criteria. The patient was diagnosed with AIP complicated by splenic vein obstruction, gastric varices, splenomegaly, and sclerosing cholangitis. Oral administration of 30 mg/d prednisolone for 4 wk was used to induce remission, and the dose was tapered by 5 mg every 2 wk to a maintenance dose of 5 mg/d. However, a CT scan showed no improvement of the pancreatic lesion, and EGD showed no improvement of the gastric varices. Because steroid therapy was not effective, maintenance therapy was discontinued 5 mo after the initial treatment. One year after hospital admission, the patient was followed in the clinic without treatment.

There are few reports of autoimmune pancreatitis complicated by gastric varices. The effects of steroid therapy on the varices is unknown[6]. However, the reported 8%[7] frequency of splenic vein obstruction in patients with chronic pancreatitis indicates that it is not a rare complication. Splenic vein obstruction causes a localized form of portal hypertension, known as sinistral portal hypertension, which leads to the formation of gastric varices along the fundus and the greater curvature of the stomach due to increased blood flow through the short gastric veins or the gastroepiploic vein[8]. From 1999 to 2011, our hospital treated 20 consecutive patients with AIP who fulfilled either the 2006 Clinical Diagnostic Criteria of The Japan Pancreas Society or the Asia diagnostic criteria. Splenic vein obstruction was confirmed in 4 of the patients (20%) using CT, and 3 of the 4 patients (15%) had gastric varices.

The clinical course of these three cases varied depending on the presence of splenomegaly. In case 1, splenomegaly was not detected at the time of diagnosis. Gastric varices disappeared as the AIP improved using steroid therapy; In case 2, splenomegaly was detected at the time of diagnosis. The gastric varices did not improve, although the AIP improved using steroid therapy; In case 3, splenomegaly was detected at the time of diagnosis. Neither the gastric varices nor the AIP improved with steroid therapy. These three cases suggest that gastric varices complicating AIP without splenomegaly may improve using steroid therapy.

The pathogenetic hypothesis of splenic vein obstruction has been related to many factors: compression by a pseudocyst or an enlarged pancreatic parenchyma and secondary involvement of the vein by surrounding edema, cellular infiltration, and the fibroinflammatory process[9]. Whether the splenic vein obstruction is formed by mechanical force or inflammatory infiltration, the obstruction will become an irreversible thrombosis over time. Although the AIP improved in case 2, the splenic vein obstruction, which had likely progressed into a thrombosis, was irreversible. A gastrorenal shunt or other collateral veins that drain into the systemic circulation were not detected on CT scans in any of the three cases. Development of congestive splenomegaly may have been dependent on the length of time the patients had been affected with sinistral portal hypertension. These three cases indicate the need to reperfuse the obstructed splenic vein before the development of splenomegaly, otherwise the obstruction becomes irreversible. According to a nationwide survey by the Research Committee of Intractable Pancreatic Diseases conducted by the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan, the remission rate of steroid-treated AIP is 98%[10]. However, rare cases of steroid-refractory AIP can occur. Kamisawa et al[11] reported the development of pancreatic atrophy in 5 out of 23 patients with AIP. Takayama et al[12] reported that AIP has the potential to be a progressive disease with pancreatic stones. These reports suggest that recurrent cases of AIP can turn into chronic pancreatitis-like lesions during long-term follow-up and become refractory to steroid therapy. In case 3, the AIP was refractory to steroid therapy. Because the enlargement of the pancreas was not prominent and a pancreatic stone was detected, the lesion was likely the result of recurrent inflammation of AIP.

The role of a prophylactic splenectomy in asymptomatic patients with splenic vein obstruction and gastric varices remains controversial. Badley concluded that the benefit of preventing possible bleeding of the varices outweighs the risk of postsplenectomy sepsis[13], although Bernades et al[7] reported that the risk of variceal bleeding is lower than previously reported. In cases 2 and 3, we did not perform a prophylactic splenectomy or partial splenic embolization because the patients opted for a watchful waiting approach.

The indications for steroid therapy in patients with AIP are symptoms such as obstructive jaundice, abdominal pain, back pain and the presence of symptomatic extrapancreatic lesions[1]. However, some patients with AIP improve spontaneously[1,14]. The treatment of asymptomatic patients with AIP remains controversial. Based on the potential risk and benefits, these three cases suggest that patients with AIP and gastric varices or splenic vein obstruction without splenomegaly should be treated with steroids before pancreatic lesions or splenic vein obstructions become irreversible. Because this study only included three cases, it is necessary to collect data on more patients with AIP complicated by gastric varices to effectively evaluate this hypothesis.

In conclusion, we treated 3 cases of autoimmune pancreatitis complicated with gastric varices. Gastric varices or splenic vein obstruction without splenomegaly may be an indication for steroid therapy in patients with AIP.

Peer reviewers: Dr. Terumi Kamisawa, Department of Internal Medicine, Tokyo Metropolitan Komagome Hospital, Honkomagome, Bunkyo-ku 31822, Tokyo; Kazuichi Okazaki, Professor, The Third Department of Internal Medicine, Kansai Medical University, 2-3-1 Shinmachi, Hirakata, Osaka 573-1191, Japan

S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor A E- Editor Zhang DN

| 1. | Kamisawa T, Okazaki K, Kawa S, Shimosegawa T, Tanaka M. Japanese consensus guidelines for management of autoimmune pancreatitis: III. Treatment and prognosis of AIP. J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:471-477. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 192] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 204] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Yoshida K, Toki F, Takeuchi T, Watanabe S, Shiratori K, Hayashi N. Chronic pancreatitis caused by an autoimmune abnormality. Proposal of the concept of autoimmune pancreatitis. Dig Dis Sci. 1995;40:1561-1568. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1044] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 891] [Article Influence: 30.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Okazaki K, Chiba T. Autoimmune related pancreatitis. Gut. 2002;51:1-4. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 276] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 305] [Article Influence: 13.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Pickartz T, Mayerle J, Lerch MM. Autoimmune pancreatitis. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;4:314-323. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 81] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Gardner TB, Chari ST. Autoimmune pancreatitis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2008;37:439-60, vii. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 57] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Fuke H, Shimizu A, Shiraki K. Gastric varix associated with autoimmune pancreatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:xxxii. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bernades P, Baetz A, Lévy P, Belghiti J, Menu Y, Fékété F. Splenic and portal venous obstruction in chronic pancreatitis. A prospective longitudinal study of a medical-surgical series of 266 patients. Dig Dis Sci. 1992;37:340-346. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 129] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sakorafas GH, Tsiotou AG. Splenic-vein thrombosis complicating chronic pancreatitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1999;34:1171-1177. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 12] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lillemoe KD, Yeo CJ. Management of complications of pancreatitis. Curr Probl Surg. 1998;35:1-98. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Nishimori I, Okazaki K, Kawa S, Otsuki M. Treatment for autoimmune pancreatitis. J Biliary Tract Pancreas. 2007;28:961-966. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Kamisawa T, Yoshiike M, Egawa N, Nakajima H, Tsuruta K, Okamoto A. Treating patients with autoimmune pancreatitis: results from a long-term follow-up study. Pancreatology. 2005;5:234-238; discussion 238-240. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 112] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Takayama M, Hamano H, Ochi Y, Saegusa H, Komatsu K, Muraki T, Arakura N, Imai Y, Hasebe O, Kawa S. Recurrent attacks of autoimmune pancreatitis result in pancreatic stone formation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:932-937. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 140] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Bradley EL. The natural history of splenic vein thrombosis due to chronic pancreatitis: indications for surgery. Int J Pancreatol. 1987;2:87-92. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |