Published online Mar 21, 2011. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i11.1480

Revised: December 11, 2010

Accepted: December 18, 2010

Published online: March 21, 2011

AIM: To investigate the predictors of success in step-down of proton pump inhibitor and to assess the quality of life (QOL).

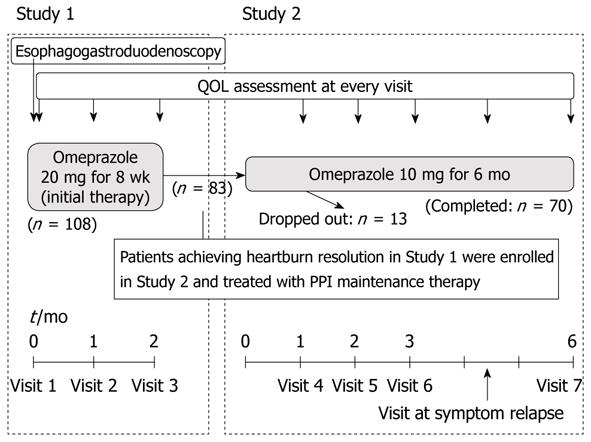

METHODS: Patients who had heartburn twice a week or more were treated with 20 mg omeprazole (OPZ) once daily for 8 wk as an initial therapy (study 1). Patients whose heartburn decreased to once a week or less at the end of the initial therapy were enrolled in study 2 and treated with 10 mg OPZ as maintenance therapy for an additional 6 mo (study 2). QOL was investigated using the gastrointestinal symptom rating scale (GSRS) before initial therapy, after both 4 and 8 wk of initial therapy, and at 1, 2, 3, and 6 mo after starting maintenance therapy.

RESULTS: In study 1, 108 patients were analyzed. Their characteristics were as follows; median age: 63 (range: 20-88) years, sex: 46 women and 62 men. The success rate of the initial therapy was 76%. In the patients with successful initial therapy, abdominal pain, indigestion and reflux GSRS scores were improved. In study 2, 83 patients were analyzed. Seventy of 83 patients completed the study 2 protocol. In the per-protocol analysis, 80% of 70 patients were successful for step-down. On multivariate analysis of baseline demographic data and clinical information, no previous treatment for gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) [odds ratio (OR) 0.255, 95% CI: 0.06-0.98] and a lower indigestion score in GSRS at the beginning of step-down therapy (OR 0.214, 95% CI: 0.06-0.73) were found to be the predictors of successful step-down therapy. The improved GSRS scores by initial therapy were maintained through the step-down therapy.

CONCLUSION: OPZ was effective for most GERD patients. However, those who have had previous treatment for GERD and experience dyspepsia before step-down require particular monitoring for relapse.

- Citation: Tsuzuki T, Okada H, Kawahara Y, Takenaka R, Nasu J, Ishioka H, Fujiwara A, Yoshinaga F, Yamamoto K. Proton pump inhibitor step-down therapy for GERD: A multi-center study in Japan. World J Gastroenterol 2011; 17(11): 1480-1487

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v17/i11/1480.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v17.i11.1480

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is defined as the reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus; it may lead to esophagitis, reflux symptoms sufficient to impair quality of life (QOL), and/or long-term complications[1]. In Japan, GERD was, in the past, considered to be a rare disease, but is now one of the most common chronic disorders. One systematic review of Japan[2] reported that 15.4% (725) of 4723 patients had heartburn twice or more per week; 42.2% had symptoms of heartburn, including those who had heartburn once or less per week; and 16.7% (602) of 3608 patients had reflux esophagitis. Some papers have suggested that the increasing prevalence of GERD is a result of rising acid secretion in the general Japanese population, caused by the westernization of lifestyle and diet (to include dairy products) and decline in Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection[3].

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) provide the highest levels of symptom relief, healing of esophagitis, and prevention of relapse and complications[4]. They are the first choice for therapy in most GERD patients with or without esophageal mucosal injury[5,6]. However, PPIs cost more than do other acid-inhibiting agents. Some papers suggest that long-term PPI therapy, particularly at high doses, is associated with increased risks of community-acquired pneumonia[7] and hip fracture[8]. Therefore, if possible, PPIs should be administered at the lower dose. Full-dose PPI first “step-down” therapy is superior, both to administering histamine-2-receptor antagonist (H2RA) first and low-dose PPI first “step-up” strategy, with regard to both efficacy and cost-effectiveness[9,10]. However, some patients experience a recurrence after step-down[11,12].

On the other hand, there is increasing interest in evaluating the QOL of patients with GERD. It is widely accepted that patients with GERD have a decreased QOL compared with the general population[13-15], similar to that seen in patients with other chronic diseases[16]. Consequently, patient-reported symptoms and QOL are important in assessing treatment outcome.

In this article, we describe 2 series of studies devised to investigate the predictors of success in step-down PPI therapy and to assess symptom-related QOL as determined by a questionnaire administered during GERD therapy.

Subjects: This multicenter trial was conducted at Okayama University Hospital and 20 affiliated hospitals in Japan. The study protocol was approved by the local institutional review boards of Okayama University Hospital and of each of the affiliated hospitals. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient before their enrollment in this study.

The major eligibility criteria were the following: heartburn that occurs twice a week or more; age 20 years or older; and either erosive esophagitis (EE) or non-erosive reflux disease. The exclusion criteria were as follows: use of PPIs within 1 mo of the start of the study; open gastric or duodenal ulcer; malignant neoplasm; serious systemic disease; and pregnancy, signs of pregnancy, or occurrence during a lactation period.

Study design: Patients who met the above-mentioned inclusion criteria were asked to complete the Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale (GSRS) to assess gastrointestinal symptom-related QOL. Additional information, including demographic data, height and weight measurements used to assess body mass index (BMI), comorbid conditions, concurrent medication use, history of GERD symptoms, and previous GERD medication, was collected at the initial visit. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was performed to assess hiatus hernia, esophagitis, and upper gastrointestinal disorders before treatment.

PPI therapy was performed according to the following strategy (Figure 1): Patients were treated with 20 mg of omeprazole (OPZ) once daily for 8 wk as an initial therapy. GSRS results were evaluated before the initial therapy and after both 4 and 8 wk of treatment.

The primary analysis was to investigate the rate of success of initial PPI therapy. Success was defined as having heartburn once a week or less at the end of the initial therapy. Secondary analyses examined changes in QOL during the initial treatment of PPI.

Subjects: Patients whose incidence of heartburn decreased to once a week or less at the end of study 1 (the initial therapy) were enrolled in this study. Study 2 subjects included patients who achieved complete remission and those who achieved partial remission of GERD symptoms.

Study design: Patients received PPI step-down therapy: namely, 10 mg of OPZ once daily for 6 mo (Figure 1). QOL related to gastrointestinal symptoms was evaluated at 1, 2, 3, and 6 mo after the beginning of maintenance therapy. If heartburn recurred twice a week or more during maintenance therapy, the treatment was stopped and the QOL at that time was evaluated.

The primary analysis was designed to identify predictors of subjects who were successful in PPI step-down therapy-defined as having no recurrence of heartburn 6 mo after PPI step-down. Secondary analyses examined changes in QOL during the maintenance treatment of PPI.

The severity of esophagitis was established by endoscopic examination using the modified Los Angeles (LA) classification of Grade A to D, with Grade M and N[17]. This adds an additional grade N (defined as no apparent mucosal change) and grade M (defined as minimal changes in the mucosa, such as erythema and/or whitish turbidity). The modified LA system has recently become widely used in Japan[18]. A diagnosis of hiatus hernia was made when the retroflexed endoscope, under the condition of gastric inflation, showed gaping esophageal lumen allowing the squamous epithelium to be viewed below[19]. Atrophic gastritis was diagnosed by endoscopy using the Kimura-Takemoto endoscopic classification[20], in which atrophic gastritis was divided largely into closed type (C-type) and open type (O-type) by the location of an atrophic border detected by endoscopy. C-type means that the atrophic border remains on the lesser curvature of the stomach, while O-type means that the atrophic border no longer exists on the lesser curvature but extends along the anterior and posterior walls of the stomach. In this study, atrophic gastritis was defined as only the O-type of the Kimura-Takemoto classification: the endoscopic diagnosis of C-type atrophic gastritis may be unreliable because of interobserver variation.

Symptom-related QOL was assessed using the GSRS. The GSRS is a disease-specific 15-item questionnaire developed, based on reviews of gastrointestinal symptoms and clinical experience, to evaluate common symptoms of gastrointestinal disorders[21,22]. Patients are asked to numerically score their subjective symptoms on a Likert-type scale of 1-7. The sum of the scores for all 15 items is regarded as the total GSRS score. Because each of the 15 questions can be scored from 1 to 7, the minimum total score obtainable is 15, and the maximum total score is 105. This total is then divided by 15 to obtain the overall GSRS score, from a minimum of 1 to a maximum overall score of 7. Furthermore, the scores for the 5 symptom categories (reflux, abdominal pain, dyspepsia, diarrhea, and constipation) are obtained by calculating the means of the scores on the items for each symptom category. The higher the overall score, the more severe the symptoms[23].

All categorical variables were analyzed using chi-square or Fisher’s exact test.

Analyses of efficacy parameters were performed on 2 populations: the intention-to-treat (ITT) and the per-protocol (PP) populations.

The time to first symptom relapse after PPI step-down was assessed by Kaplan-Meier analysis. To determine the predictors of successful step-down, univariate and multivariable logistic regression analyses were planned. Variables found in the univariate analysis to be significantly associated with successful step-down were included in a multivariable logistic regression analysis. Changes in QOL were analyzed with paired t tests. An overall significance level of 5% was used in all tests. Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS version 11.0 using Windows.

Between April 2004 and March 2007, 108 eligible patients were entered into study 1. For reasons that were apparently not causally related to the medication, 21 out of 108 patients dropped out of the study. The demographic characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1. In the ITT analysis, 83 (76%) of 108 patients completed the 8 wk of initial therapy successfully. In the PP analysis, 83 (95.4%) of 87 patients were successful. The reasons for failure of the 4 patients in initial therapy were insufficiency of GERD symptoms in 2 patients and side effects of PPI in the other 2. The adverse reactions were diarrhea (one patient) and tinnitus (one patient). The reasons for dropout of 21 patients in study 1 were as follows: one patient withdrew her consent before the initial therapy, 12 patients never came to the hospital after the initial visit without excuse, 8 patients never came to the hospital after the second visit without excuse (3 of them still had symptoms of reflux at that time), the others got relief of reflux symptoms.

| Characteristic | ITT population(n = 108) |

| Gender | |

| Male/female | 62 (57.4)/46 (42.6) |

| Age (yr) | |

| Range | 20-88 |

| Median | 63 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | |

| ≤ 24.9 (normal or below normal) | 77 (71.3) |

| 25-29.9 (overweight) | 28 (25.9) |

| ≥ 30 (obese) | 3 (2.8) |

| Previous treatment for GERD | 38 (35.2) |

| Duration of GERD symptoms before initial treatment (mo) | |

| < 1 | 21 (19.4) |

| 1-11 | 47 (43.5) |

| ≥ 12 | 40 (37.0) |

| Tobacco use | 24 (22.2) |

| Alcohol use | 44 (40.7) |

| Helicobacter pylori infection | 31 (28.7) |

| The modified Los Angeles Classification | |

| N/M | 20 (18.5)/17 (15.7) |

| A/B | 32 (29.6)/32 (29.6) |

| C/D | 5 (4.6)/2 (1.9) |

| Atrophic gastritis1 | 18 (16.7) |

| Hiatus hernia | 57 (52.8) |

| Ischemic heart disease | 9 (8.3) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 11 (10.2) |

| Bronchial asthma | 4 (3.7) |

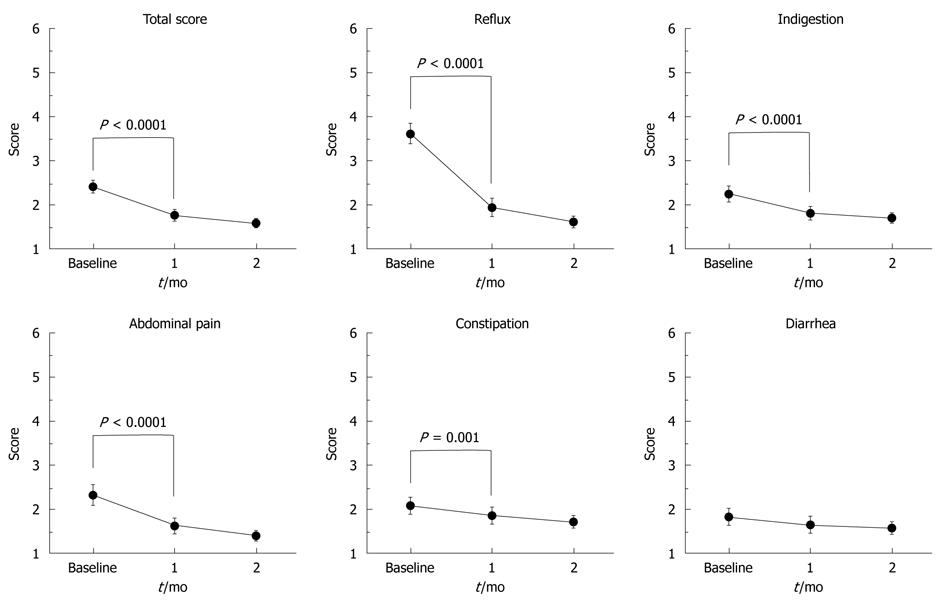

Symptom-related QOL analysis was performed for subjects who successfully completed the initial therapy. The changes in QOL during therapy are shown in Figure 2. The GSRS total score significantly improved from the baseline after 4-wk treatment (P < 0.0001). Of the 83 patients who had heartburn once a week or less at the end of the initial therapy, 55 patients (66%) had a reflux score of one, indicating no symptoms, 23 patients (28%) had a score of two, and the others had a score of three. In other words, 78 (94%) of 83 patients having heartburn once a week or less complained of little or no symptoms of reflux at the end of the initial therapy. Not only the GSRS reflux scores but also the abdominal pain, indigestion, and constipation scores showed significant improvements (P < 0.0001).

Eighty three eligible patients who had heartburn resolution after the initial 8 wk of therapy were recruited for study 2-step-down treatment as maintenance therapy. Thirteen patients dropped out during the maintenance therapy without recurrence or adverse reactions; 70 patients completed the study 2 protocol. Of 13 dropout patients, one patient experienced exaggerated symptoms of reflux before dropout, nine experienced complete resolution of reflux symptoms before dropout, and the others never came to the hospital after starting the step-down therapy.

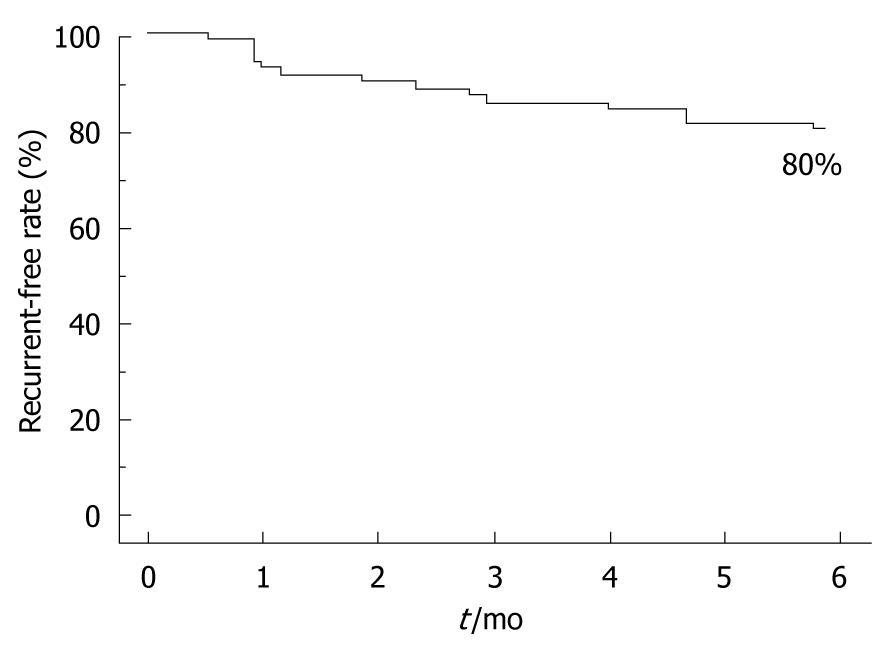

Demographic and baseline characteristics of the study 2 population are summarized in Table 2. In the ITT analysis, 56 (67.5%) of 83 patients did not suffer a recurrence during maintenance therapy. In the PP analysis, 56 (80%) of 70 patients were successful in step-down therapy (Figure 3). Of 14 failures, 10 occurred within the first 3 mo of maintenance therapy. The mean time to failure was 56 d (range, 16-180 d).

| Characteristic | ITT population(n = 83) |

| Gender | |

| Male/female | 50 (60.2)/33 (39.8) |

| Age (yr) | |

| Range | 25-88 |

| Median | 64 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | |

| ≤ 24.9 (normal or below normal) | 60 (72.3) |

| 25-29.9 (overweight) | 20 (24.1) |

| ≥ 30 (obese) | 3 (3.6) |

| Previous treatment for GERD | 27 (32.5) |

| Duration of GERD symptoms before initial treatment (mo) | |

| < 1 | 14 (16.9) |

| 1-11 | 42 (50.6) |

| ≥ 12 | 27 (32.5) |

| Tobacco use | 21 (25.3) |

| Alcohol use | 39 (47.0) |

| Helicobacter pylori infection | 27 (32.5) |

| The modified Los Angeles Classification | |

| N/M | 15 (18.1)/9 (10.8) |

| A/B | 24 (28.9)/30 (36.1) |

| C/D | 3 (3.6)/2 (2.4) |

| Atrophic gastritis1 | 15 (18.1) |

| Hiatus hernia | 44 (53.0) |

| Ischemic heart disease | 8 (9.6) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 7 (8.4) |

| Bronchial asthma | 3 (3.6) |

| GERD symptom before step-down | |

| Complete remission | 55 (66.3) |

| Partial remission | 28 (33.7) |

In the univariate analysis of the ITT population, there were no significant predictors for successful step-down. In the univariate analysis of the PP population (n = 70), the significant predictors for successful step-down were: complete remission of GERD symptoms before step-down (P = 0.042), no past history of GERD (P = 0.019), no H2RA use at baseline (P = 0.023), and better GSRS total (P = 0.045) and indigestion (P = 0.011) scores at the beginning of step-down (Table 3). In a multivariate analysis of the PP population, no past history of GERD (P = 0.047) and a better GSRS indigestion score at the beginning of step-down (P = 0.014) were predictive factors for successful step-down (Table 4).

| Variable | ITT population(n = 83) | PP population(n = 70) | ||

| OR | P | OR | P | |

| Age | 0.984 | 0.428 | 0.965 | 0.212 |

| BMI | 3.667 | 0.073 | 2.108 | 0.251 |

| Past history of treatment for GERD | 0.497 | 0.161 | 0.228 | 0.019 |

| Duration of GERD symptoms | 1.004 | 0.416 | 1.199 | 0.536 |

| Alcohol use | 1.182 | 0.732 | 1.486 | 0.487 |

| Tobacco use | 1.125 | 0.834 | 0.692 | 0.531 |

| Helicobacter pylori infection | 0.963 | 0.942 | 1.500 | 0.577 |

| Erosive esophagitis | 2.599 | 0.062 | 1.402 | 0.620 |

| LA classification | 1.431 | 0.070 | 1.238 | 0.360 |

| Atrophic gastritis | 0.930 | 0.906 | 0.568 | 0.411 |

| Hiatus hernia | 1.333 | 0.566 | 1.476 | 0.545 |

| complete remission of GERD symptoms before step-down | 1.355 | 0.539 | 3.676 | 0.042 |

| GSRS total score (at the beginning of step-down) | 0.771 | 0.647 | 0.208 | 0.045 |

| Reflux score in GSRS (at the beginning of step-down) | 0.917 | 0.803 | 0.477 | 0.072 |

| Indigestion score in GSRS (at the beginning of step-down) | 0.594 | 0.209 | 0.218 | 0.011 |

| Variable | OR | 95% CI | P |

| Past history of treatment for GERD | 0.255 | 0.066-0.980 | 0.047 |

| Indigestion score in GSRS (at the beginning of step down) | 0.214 | 0.063-0.731 | 0.014 |

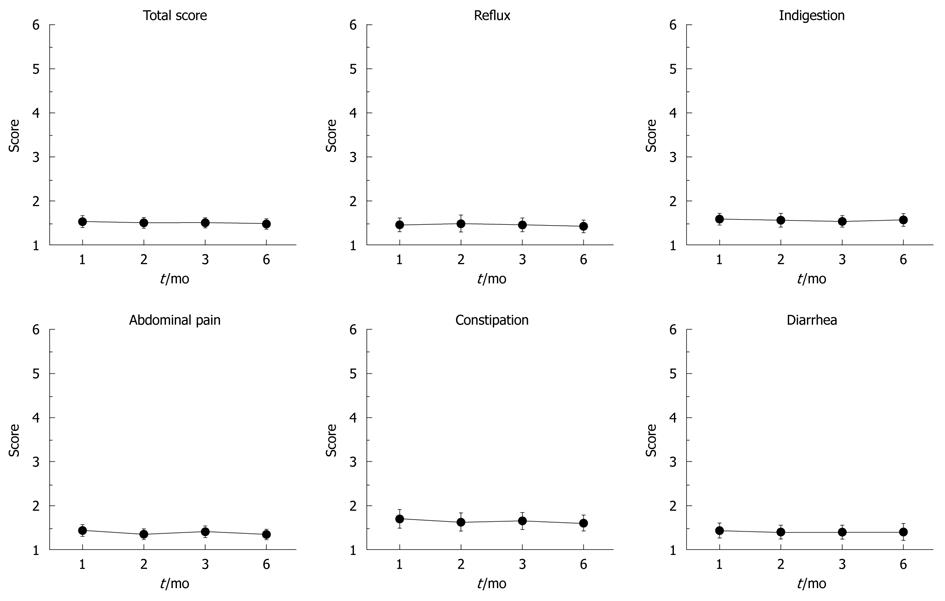

Symptom-related QOL analysis was performed on subjects for whom maintenance therapy was successful. The changes in QOL during therapy are shown in Figure 3. The improved GSRS scores of initial therapy were maintained throughout step-down therapy (Figure 4).

In study 1, we investigated the effectiveness of OPZ (20 mg) for the initial treatment of GERD and changes in symptom-related QOL during the initial therapy. Previous studies of patients with GERD using PPIs showed that 64%-88% of patients with typical reflux symptoms respond to PPI therapy[24-26]. The heartburn resolution rate of the present study (95.4%) was higher than that of previous studies. It is reasonable to assume that a less rigorous end-point of the present study, namely having heartburn once a week or less, would have resulted in a higher rate of symptom response.

The assessment of symptom-related QOL in study 1 demonstrated that PPI therapy for GERD produced an improvement not only in reflux symptoms but also in other symptoms, such as abdominal pain and symptoms of indigestion. We could not exclude other factors possibly related to improvement of those symptoms in addition to the drug effect, for instance, regression toward mean, the nature of symptom fluctuation, Hawthorn effect, etc. This result confirms that most GERD patients have other gastrointestinal symptoms (dyspepsia and abdominal pain), which, if they are related to acid reflux, are improved by acid suppressants[27-29].

In study 2, we determined the characteristics of GERD patients whose heartburn relief achieved by the initial therapy could be sustained through maintenance therapy with a half-dose of PPI therapy. The results showed that 80% of subjects whose symptoms were controlled with full-dose PPI could be successfully managed with a lower dose of PPI for 6 mo. The success of step-down was predicted only by no previous treatment for GERD and a better GSRS indigestion score at the beginning of step-down. Inadomi et al. showed that the success of step-down was predicted only by the duration of PPI use before the study[30]. This result is similar to that of the present study in that both studies suggest that the other baseline patient factors likely to influence the efficacy of step-down therapy, such as BMI, H. pylori infection, LA classification and erosive esophagitis in endoscopic findings, and hiatus hernia were not predictors of successful step-down. There was no significant difference in the therapeutic outcome according to LA classification, probably because there were a few patients with severe esophagitis; i.e. grade C or D, in the present study.

It is interesting that the indigestion score after initial therapy is associated with the success of step-down. This result means that patients who are in remission from GERD symptoms, but have dyspeptic symptoms after initial therapy, need stronger acid-suppression than do those who have no symptoms after a standard dose of PPI therapy. The patients with PPI non-responsive dyspepsia may have delayed gastric emptying, which could increase the frequency of transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxation and stimulate gastric acid secretion[31,32]. This is probably the reason why stronger acid-suppression is necessary for heartburn control. These results demonstrate that physicians who treat GERD should ask patients about several conditions in addition to reflux.

There are several limitations to the present study. First, there were a relatively large number of dropouts during maintenance therapy. So, when analysis regarded dropouts as failures on the basis of the ITT principle, there were no predictors for successful step-down. When the pursuit period of study 2 was shortened from 6 mo to 3 mo, ITT analysis showed several statistically significant differences. In a univariate analysis, significant predictors for successful step-down were no H2RA use at baseline (P = 0.05) and a better GSRS indigestion score at the beginning of step-down (P = 0.009). In a multivariate analysis, only the better GSRS indigestion scores at the beginning of step-down (P = 0.016) were predictive factors for successful step-down. In the present study, most patients had mild esophagitis, which would probably benefit from the mild treatment or even by non-drug therapy, for instance, light and early dinner, inclined bed, and straight posture[33]. This may explain why many patients dropped out. Indeed, most patients discontinued therapy because they had no further symptoms. Furthermore, it cannot be denied that some patients with successful step-down may have had good control of their GERD symptoms by non-drug therapy because we did not take into account the recommended life-style and dietary changes in our study protocol.

Second, in this study, many patients (75% of patients who received 8 wk of initial therapy) did not have the post-treatment endoscopic assessment. Some patients in clinical remission after the initial therapy did not have endoscopic remission. If all subjects underwent post-treatment endoscopy, the endoscopic findings could be the candidate predictor of successful step-down.

Third, cytochrome P450 2C19 genotypic differences, which are related to the cure rates for GERD with PPIs (OPZ and lansoprazole)[11,34,35], are not considered in this study. This factor could also be the candidate predictor[11,36]. The analysis of these factors may provide more information for GERD treatment.

In conclusion, our study revealed that the majority of patients whose heartburn decreased to once a week or less on full-dose OPZ therapy can be successfully stepped-down to a half-dose of PPI. The predictors of successful step-down are no previous treatment for GERD and a better indigestion score in the GSRS at the beginning of step-down. Improvement of symptom-related QOL was maintained throughout the step-down therapy.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is one of the most common disorders not only in the Western world but also in Japan, with increasing prevalence and incidence in the last decades. Typical GERD symptoms include heartburn, acid regurgitation into the pharynx, and dysphagia. The GERD patients sometimes suffer from chest pain, dyspepsia, and other atypical symptoms including coughing, wheezing, hoarseness, etc.

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are the first choice of therapy for most GERD patients with or without esophageal mucosal injury. Full dose PPI-first “step-down” therapy is superior to histamin-2-receptor antagonist (H2RA) or low dose PPI-first “step-up” strategy with regard to both efficacy and cost-effectiveness. However, there is no clear consensus regarding the predictors for successful step-down. Treatment of GERD aims not only at healing esophagitis but also at managing the symptoms of GERD associated with decreased quality of life (QOL). In this study, we investigated the predictors of success in step-down PPI therapy and assessed the symptom-related QOL.

Many studies evaluating the efficacy of PPI in terms of the symptoms of GERD patients in the Western world did not evaluate the grade of esophagitis with endoscopy. Recently, many studies in Japan have focused mainly on non-erosive reflux disease (NERD) patients. The data of this study originated from GERD patients (both erosive gastritis and NERD) who were diagnosed with endoscopy. Therefore, the results may reflect those of the GERD patients in the Japanese general population and can be considered useful for GERD treatment in the clinical practice.

By considering the clinical features of GERD patients with recurrence during the step-down therapy, this study’s findings may suggest new strategies for additional PPI dose reduction including every-other-day administration, on-demand therapy, step-down to H2RA, and drug-free management.

The authors investigated the effect of omeprazole and subsequent step-down maintenance therapy in patients with GERD. This study must be a very interesting topic for readers in view of the rarity of PPI outcome studies in the Asia pacific region.

Peer reviewers: Josep M Bordas, MD, Department of Gastroenterology IMD, Hospital Clinic”, Llusanes 11-13 at, Barcelona 08022, Spain; Myung-Gyu Choi, MD, Professor of Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Internal Medicine, Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital, The Catholic University of Korea, 505, Banpo-Dong, Seocho-Gu, Seoul 137-040, South Korea

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor O’Neill M E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | Dent J, Armstrong D, Delaney B, Moayyedi P, Talley NJ, Vakil N. Symptom evaluation in reflux disease: workshop background, processes, terminology, recommendations, and discussion outputs. Gut. 2004;53 Suppl 4:iv1-i24. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Kouzu T, Hishikawa E, Watanabe Y, Inoue M, Satou T. [Epidemiology of GERD in Japan]. Nippon Rinsho. 2007;65:791-794. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Furukawa N, Iwakiri R, Koyama T, Okamoto K, Yoshida T, Kashiwagi Y, Ohyama T, Noda T, Sakata H, Fujimoto K. Proportion of reflux esophagitis in 6010 Japanese adults: prospective evaluation by endoscopy. J Gastroenterol. 1999;34:441-444. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Klinkenberg-Knol EC, Nelis F, Dent J, Snel P, Mitchell B, Prichard P, Lloyd D, Havu N, Frame MH, Romàn J. Long-term omeprazole treatment in resistant gastroesophageal reflux disease: efficacy, safety, and influence on gastric mucosa. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:661-669. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Savarino V, Dulbecco P. Optimizing symptom relief and preventing complications in adults with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Digestion. 2004;69 Suppl 1:9-16. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | DeVault KR, Castell DO. Updated guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:190-200. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Laheij RJ, Sturkenboom MC, Hassing RJ, Dieleman J, Stricker BH, Jansen JB. Risk of community-acquired pneumonia and use of gastric acid-suppressive drugs. JAMA. 2004;292:1955-1960. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | Yang YX, Lewis JD, Epstein S, Metz DC. Long-term proton pump inhibitor therapy and risk of hip fracture. JAMA. 2006;296:2947-53. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | Habu Y, Maeda K, Kusuda T, Yoshino T, Shio S, Yamazaki M, Hayakumo T, Hayashi K, Watanabe Y, Kawai K. "Proton-pump inhibitor-first" strategy versus "step-up" strategy for the acute treatment of reflux esophagitis: a cost-effectiveness analysis in Japan. J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:1029-1035. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Mine S, Iida T, Tabata T, Kishikawa H, Tanaka Y. Management of symptoms in step-down therapy of gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20:1365-1370. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Furuta T, Sugimoto M, Kodaira C, Nishino M, Yamade M, Ikuma M, Shirai N, Watanabe H, Umemura K, Kimura M. CYP2C19 genotype is associated with symptomatic recurrence of GERD during maintenance therapy with low-dose lansoprazole. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;65:693-698. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 12. | Lauritsen K, Devière J, Bigard MA, Bayerdörffer E, Mózsik G, Murray F, Kristjánsdóttir S, Savarino V, Vetvik K, De Freitas D. Esomeprazole 20 mg and lansoprazole 15 mg in maintaining healed reflux oesophagitis: Metropole study results. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:333-341. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 13. | Revicki DA, Wood M, Maton PN, Sorensen S. The impact of gastroesophageal reflux disease on health-related quality of life. Am J Med. 1998;104:252-258. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 14. | Prasad M, Rentz AM, Revicki DA. The impact of treatment for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease on health-related quality of life: a literature review. Pharmacoeconomics. 2003;21:769-790. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 15. | Pace F, Negrini C, Wiklund I, Rossi C, Savarino V. Quality of life in acute and maintenance treatment of non-erosive and mild erosive gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:349-356. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 16. | Kulig M, Leodolter A, Vieth M, Schulte E, Jaspersen D, Labenz J, Lind T, Meyer-Sabellek W, Malfertheiner P, Stolte M. Quality of life in relation to symptoms in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease-- an analysis based on the ProGERD initiative. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18:767-776. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 17. | Lundell LR, Dent J, Bennett JR, Blum AL, Armstrong D, Galmiche JP, Johnson F, Hongo M, Richter JE, Spechler SJ. Endoscopic assessment of oesophagitis: clinical and functional correlates and further validation of the Los Angeles classification. Gut. 1999;45:172-180. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 18. | Miwa H, Yokoyama T, Hori K, Sakagami T, Oshima T, Tomita T, Fujiwara Y, Saita H, Itou T, Ogawa H. Interobserver agreement in endoscopic evaluation of reflux esophagitis using a modified Los Angeles classification incorporating grades N and M: a validation study in a cohort of Japanese endoscopists. Dis Esophagus. 2008;21:355-363. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 19. | Kinoshita Y, Adachi K. Hiatal hernia and gastroesophageal flap valve as diagnostic indicators in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:720-721. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 20. | Kimura K, Takemoto T. An endoscopic recognition of the atrophic border and its significance in chronic gastritis. Endoscopy. 1969;1:87-97. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 21. | Svedlund J, Sjödin I, Dotevall G. GSRS--a clinical rating scale for gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome and peptic ulcer disease. Dig Dis Sci. 1988;33:129-134. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 22. | Revicki DA, Wood M, Wiklund I, Crawley J. Reliability and validity of the Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Qual Life Res. 1998;7:75-83. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 23. | Suzuki H, Masaoka T, Sakai G, Ishii H, Hibi T. Improvement of gastrointestinal quality of life scores in cases of Helicobacter pylori-positive functional dyspepsia after successful eradication therapy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20:1652-1660. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 24. | Chiba N, De Gara CJ, Wilkinson JM, Hunt RH. Speed of healing and symptom relief in grade II to IV gastroesophageal reflux disease: a meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1798-1810. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 25. | Armstrong D, Paré P, Pericak D, Pyzyk M. Symptom relief in gastroesophageal reflux disease: a randomized, controlled comparison of pantoprazole and nizatidine in a mixed patient population with erosive esophagitis or endoscopy-negative reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2849-2857. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 26. | Fennerty MB, Johanson JF, Hwang C, Sostek M. Efficacy of esomeprazole 40 mg vs. lansoprazole 30 mg for healing moderate to severe erosive oesophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21:455-463. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 27. | Kusano M, Shimoyama Y, Kawamura O, Maeda M, Kuribayashi S, Nagoshi A, Zai H, Moki F, Horikoshi T, Toki M. Proton pump inhibitors improve acid-related dyspepsia in gastroesophageal reflux disease patients. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:1673-1677. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 28. | Quigley EM. Functional dyspepsia (FD) and non-erosive reflux disease (NERD): overlapping or discrete entities? Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;18:695-706. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 29. | Neumann H, Monkemuller K, Kandulski A, Malfertheiner P. Dyspepsia and IBS symptoms in patients with NERD, ERD and Barrett's esophagus. Dig Dis. 2008;26:243-247. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 30. | Inadomi JM, McIntyre L, Bernard L, Fendrick AM. Step-down from multiple- to single-dose proton pump inhibitors (PPIs): a prospective study of patients with heartburn or acid regurgitation completely relieved with PPIs. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1940-1944. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 31. | Holloway RH, Hongo M, Berger K, McCallum RW. Gastric distention: a mechanism for postprandial gastroesophageal reflux. Gastroenterology. 1985;89:779-784. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 32. | Kahrilas PJ, Shi G, Manka M, Joehl RJ. Increased frequency of transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxation induced by gastric distention in reflux patients with hiatal hernia. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:688-695. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 33. | Kaltenbach T, Crockett S, Gerson LB. Are lifestyle measures effective in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease? An evidence-based approach. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:965-971. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 34. | Furuta T, Ohashi K, Kosuge K, Zhao XJ, Takashima M, Kimura M, Nishimoto M, Hanai H, Kaneko E, Ishizaki T. CYP2C19 genotype status and effect of omeprazole on intragastric pH in humans. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1999;65:552-561. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 35. | Furuta T, Shirai N, Watanabe F, Honda S, Takeuchi K, Iida T, Sato Y, Kajimura M, Futami H, Takayanagi S. Effect of cytochrome P4502C19 genotypic differences on cure rates for gastroesophageal reflux disease by lansoprazole. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2002;72:453-460. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 36. | Saitoh T, Otsuka H, Kawasaki T, Endo H, Iga D, Tomimatsu M, Fukushima Y, Katsube T, Ogawa K, Otsuka K. Influences of CYP2C19 polymorphism on recurrence of reflux esophagitis during proton pump inhibitor maintenance therapy. Hepatogastroenterology. 2009;56:703-706. [Cited in This Article: ] |