Published online Dec 28, 2009. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.6126

Revised: August 25, 2009

Accepted: September 1, 2009

Published online: December 28, 2009

Pancreaticobiliary maljunction (PBM) is frequently associated with biliary cancer due to reflux of pancreatic enzymes into the choledochus, and even after surgery to correct the PBM such patients still have a risk of residual bile duct cancer. Here, we report the case of a 59-year-old female with carcinoma of the papilla of Vater which developed 2.5 years after choledochoduodenostomy for PBM. During the postoperative follow-up period, computed tomography obtained 2 years after the first operation demonstrated a tumor in the distal end of the choledochus, although she did not have jaundice and laboratory tests showed no abnormalities caused by the previous operation. As a result, carcinoma of the papilla of Vater was diagnosed at an early stage, followed by surgical cure. For early detection of periampullary cancer in patients undergoing surgery for PBM, careful long-term follow-up is needed.

- Citation: Watanabe M, Midorikawa Y, Yamano T, Mushiake H, Fukuda N, Kirita T, Mizuguchi K, Sugiyama Y. Carcinoma of the papilla of Vater following treatment of pancreaticobiliary maljunction. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15(48): 6126-6128

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v15/i48/6126.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.15.6126

Pancreaticobiliary maljunction (PBM) is a congenital anomaly defined as a union of the pancreatic and biliary ducts outside the duodenal wall[1]. Due to the loss of control by the sphincter of Oddi, pancreatic enzymes reflux into the choledochus, especially in the C-P type of maljunction, in which the common bile duct joins the main pancreatic duct[1]. Consequently, PBM is frequently associated with choledochal cyst and sometimes biliary cancer; a large survey showed that the rate of developing biliary cancer was 10.6% and 37.9% in PBM with and without choledochal dilation, respectively[2].

Once PBM is diagnosed, the development of cancer should be prevented by removal of the entire extrahepatic bile duct, even in patients without biliary dilation[3]. However, it has been reported that residual bile duct cancer could be found during the long-term follow-up period, even after termination of pancreatic enzyme reflux[4-6], and Watanabe et al[6] reported that 23 (0.7%) of 1291 patients developed residual bile duct cancer after cyst excision. Besides residual bile duct cancer, other periampullary carcinomas have been reported, but they are very rare[7,8].

In this paper, we report a case of carcinoma of the papilla of Vater that developed following treatment of PBM with choledochal dilation by choledochoduodenostomy. This is the first report of such a case, and particular attention is paid to the incidence, differential diagnosis, and treatment of periampullary neoplasms after treatment for PBM.

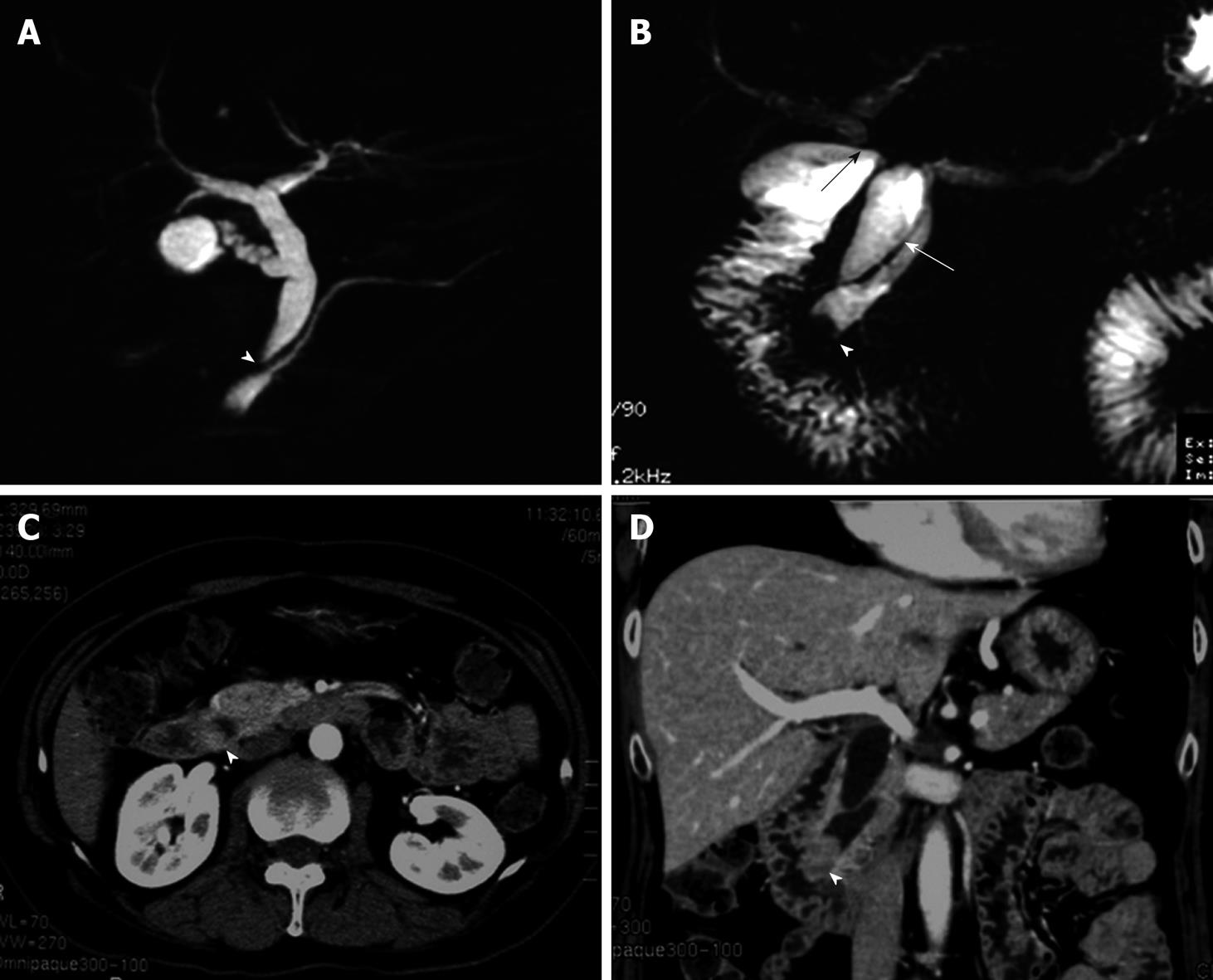

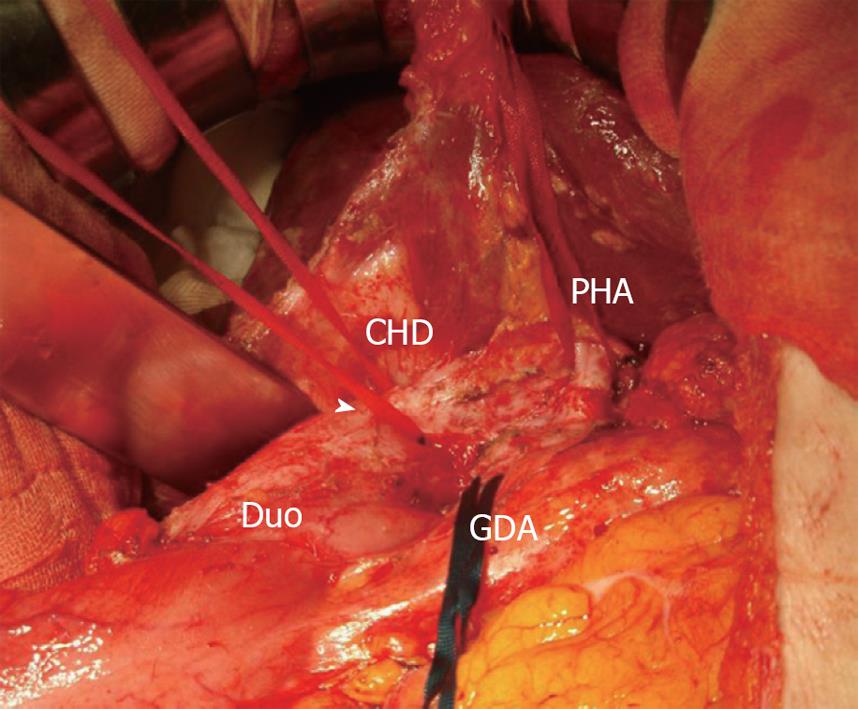

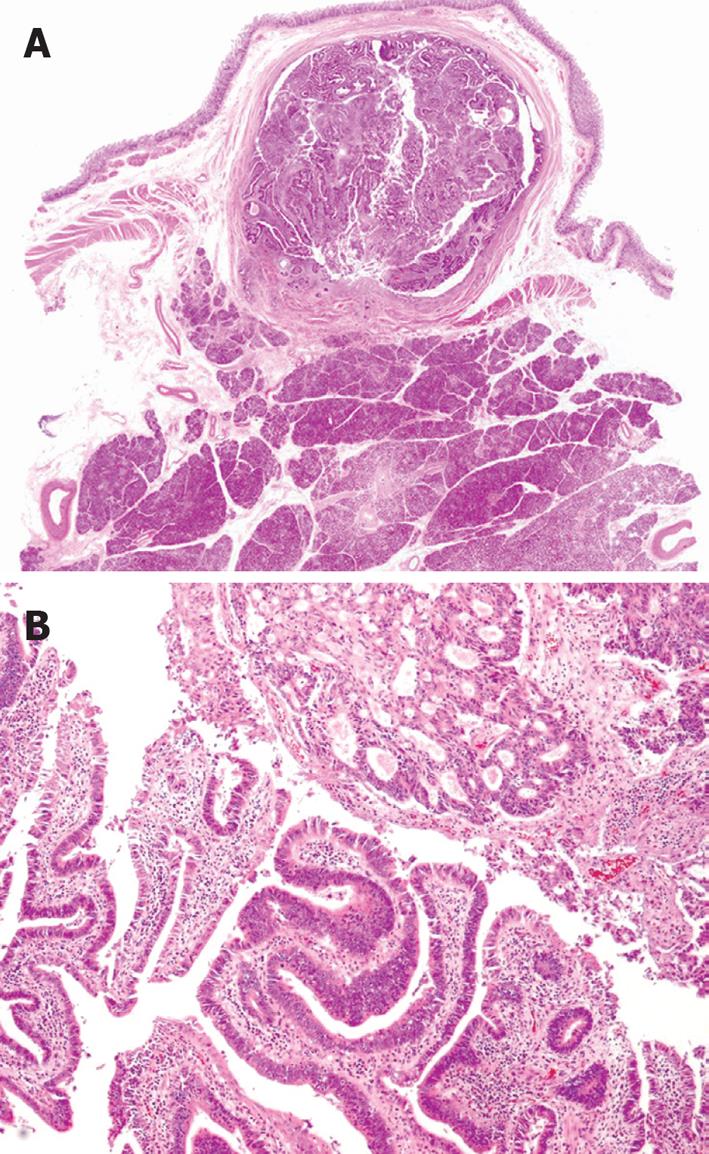

A 59-year-old female was referred to our hospital. She had undergone choledochoduodenostomy and cholecystectomy at another hospital 2.5 years earlier after diagnosis of PBM. Although imaging modalities obtained before surgery showed choledochal dilation, the minimally invasive operation was performed without excision of a choledochal cyst because the patient rejected blood transfusion preoperatively (Figure 1A). During the postoperative follow-up period, magnetic resonance choledochopancreatography demonstrated a tumor in the main pancreatic duct and in the anastomotic site of the choledochus and duodenum from the first operation (Figure 1B). Computed tomography also showed a tumor in the distal end of the residual choledochus, which had not been observed before the first operation despite bile diversion (Figure 1C and D). Endoscopic retrograde pancreatography was then performed, and a 2-cm-diameter filling defect was demonstrated at the papilla of Vater, which was shown to be adenocarcinoma on cytology. Regardless of these findings, the patient did not complain of any symptoms such as jaundice or abdominal pain, and laboratory tests, including hepatobiliary enzymes and tumor markers, showed no abnormalities. With a diagnosis of carcinoma of the papilla of Vater after choledochoduodenostomy for PBM, the patient underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy. Despite moderate adhesions due to the previous operation, we were able to find common hepatic duct which was anastomosed to the duodenum (Figure 2). After Kocher maneuver, residual extrapancreatic choledochus was easily identified behind the anastomotic region and all the residual choledochus could be removed. Because the cancerous lesion was not found at the first operation or at preoperative examination, resection of all the residual bile duct was thought to be sufficient for curative surgery. On pathology of the resected specimen, the tumor was found to be well-to-moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma of the papilla of Vater, with metastasis to the lymph nodes behind the head of the pancreas (Figure 3). The patient’s postoperative course was uneventful, and there has been no cancer recurrence 1 year after the second surgery.

Even after surgery that stops reflux of pancreatic enzymes into the choledochus and prevents the development of biliary cancer, patients with PBM still have a risk of developing residual bile duct carcinoma, both in the proximal duct and the distal end[6]. In the present case, carcinoma of the papilla of Vater was diagnosed 2 years after choledochoduodenostomy by computed tomography. In addition to complete excision of a choledochal cyst, careful long-term follow-up is necessary; the interval between excision of a choledochal cyst and cancer detection ranges from 1 to 19 years in several reports[6].

Compared with other periampullary carcinomas, including those of the duodenum, bile duct, and pancreas, survival and resectability rates of carcinoma of the papilla of Vater are relatively high[9,10]. In addition to the fact that the rate of resection is one of the predictive factors for survival[9], early detection is of great importance to provide benefit for patients with carcinoma of the papilla of Vater[11]. One of the most common manifestations at presentation in patients with carcinoma of the papilla of Vater is jaundice, as in the other periampullary carcinomas. However, jaundice is not usually observed in patients undergoing a diversion operation of the bile duct, as in the present case. Therefore, unless careful postoperative examinations of the periampullary region are performed, physicians may miss the chance to cure carcinoma of the papilla of Vater.

Compared to bile duct cancer, other residual biliary tree neoplasms are rare but can develop postoperatively. For example, a bile duct Schwannoma that developed 15 years after bypass operation and diversion of bile from a choledochal cyst has been reported[8]. Carcinoma of the papilla of Vater after choledochoduodenostomy for PBM is also very rare and has never been previously reported. Though PBM is not a risk factor for carcinoma of the papilla of Vater[12,13], which was detected only about 2 years after diversion of bile in the present case, inflammation due to the mixture of pancreatic enzymes with bile may have caused the carcinoma of the papilla of Vater in this case.

In summary, a case of carcinoma of the papilla of Vater that developed after choledochoduodenostomy for PBM was reported. In this present case, the lesion was detected at an early stage, and curative resection was performed, suggesting that careful, long-term follow-up of patients following surgery to treat PBM is necessary.

Peer reviewer: Hiroaki Nagano, MD, PhD, Associate Professor, Division of Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic Surgery and Transplantation, Department of Surgery, Graduate School of Medicine, Osaka University, 2-2 Yamadaoka E-2, Suita 565-0871 Osaka, Japan

S- Editor Li LF L- Editor Logan S E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | The Japanese Study Group on Pancreaticobiliary Maljunction (JSPBM), The Committee of JSPBM for Diagnostic Criteria. Diagnostic criteria of pancreaticobiliary maljunction. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 1994;1:219-221. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Tashiro S, Imaizumi T, Ohkawa H, Okada A, Katoh T, Kawaharada Y, Shimada H, Takamatsu H, Miyake H, Todani T. Pancreaticobiliary maljunction: retrospective and nationwide survey in Japan. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2003;10:345-351. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Todani T, Watanabe Y, Urushihara N, Morotomi Y, Maeba T. Choledochal cyst, pancreatobiliary malunion, and cancer. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 1994;1:247-251. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Ishibashi T, Kasahara K, Yasuda Y, Nagai H, Makino S, Kanazawa K. Malignant change in the biliary tract after excision of choledochal cyst. Br J Surg. 1997;84:1687-1691. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Kobayashi S, Asano T, Yamasaki M, Kenmochi T, Nakagohri T, Ochiai T. Risk of bile duct carcinogenesis after excision of extrahepatic bile ducts in pancreaticobiliary maljunction. Surgery. 1999;126:939-944. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Watanabe Y, Toki A, Todani T. Bile duct cancer developed after cyst excision for choledochal cyst. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 1999;6:207-212. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Kuga H, Yamaguchi K, Shimizu S, Yokohata K, Chijiiwa K, Tanaka M. Carcinoma of the pancreas associated with anomalous junction of pancreaticobiliary tracts: report of two cases and review of the literature. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 1998;5:113-116. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | Otani T, Shioiri T, Mishima H, Ishihara A, Maeshiro T, Matsuo A, Umekita N, Warabi M. Bile duct schwannoma developed in the remnant choledochal cyst-a case associated with total agenesis of the dorsal pancreas. Dig Liver Dis. 2005;37:705-708. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | Howe JR, Klimstra DS, Moccia RD, Conlon KC, Brennan MF. Factors predictive of survival in ampullary carcinoma. Ann Surg. 1998;228:87-94. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Qiao QL, Zhao YG, Ye ML, Yang YM, Zhao JX, Huang YT, Wan YL. Carcinoma of the ampulla of Vater: factors influencing long-term survival of 127 patients with resection. World J Surg. 2007;31:137-143; discussion 144-146. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Yokoyama N, Shirai Y, Wakai T, Nagakura S, Akazawa K, Hatakeyama K. Jaundice at presentation heralds advanced disease and poor prognosis in patients with ampullary carcinoma. World J Surg. 2005;29:519-523. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 12. | Kimura W, Futakawa N, Zhao B. Neoplastic diseases of the papilla of Vater. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2004;11:223-231. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 13. | Miyazaki M, Takada T, Miyakawa S, Tsukada K, Nagino M, Kondo S, Furuse J, Saito H, Tsuyuguchi T, Chijiiwa K. Risk factors for biliary tract and ampullary carcinomas and prophylactic surgery for these factors. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2008;15:15-24. [Cited in This Article: ] |