Published online Jul 7, 2009. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.3183

Revised: May 20, 2009

Accepted: May 27, 2009

Published online: July 7, 2009

AIM: To compare postoperative quality of life (QOL) in patients with gastric cancer treated by esophagogastrostomy reconstruction after proximal gastrectomy.

METHODS: QOL assessments that included functional outcomes (a 24-item survey about treatment-specific symptoms) and health perception (Spitzer QOL Index) were performed in 149 patients with gastric cancer in the upper third of the stomach, who had received proximal gastrectomy with additional esophagogastrostomy.

RESULTS: Fifty-four patients underwent reconstruction by esophagogastric anterior wall end-to-side anastomosis combined with pyloroplasty (EA group); 45 patients had reconstruction by esophagogastric posterior wall end-to-side anastomosis (EP group); and 50 patients had reconstruction by esophagogastric end-to-end anastomosis (EE group). The EA group showed the best postoperative QOL, such as recovery of body weight, less discomfort after meals, and less heart burn or belching at 6 and 24 mo postoperatively. However, the survival rates, surgical results and Spitzer QOL index were similar among the three groups.

CONCLUSION: Postoperative QOL was better in the EA than EP or EE group. To improve QOL after proximal gastrectomy for upper third gastric cancer, the EA procedure using a stapler is safe and feasible for esophagogastrostomy.

- Citation: Zhang H, Sun Z, Xu HM, Shan JX, Wang SB, Chen JQ. Improved quality of life in patients with gastric cancer after esophagogastrostomy reconstruction. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15(25): 3183-3190

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v15/i25/3183.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.15.3183

Although the incidence of gastric carcinoma has been decreasing continuously during the past decade, gastric cancer remains the second most common cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide. Given equivalent results with regards to survival, the impact of anastomotic methods on quality of life (QOL) becomes even more important. It has been reported that QOL is the main outcome for judging the efficacy of treatment modalities when no overall survival differences are demonstrated[1]. There is still no consensus on how to choose a reconstruction method for proximal gastrectomy in patients with upper third gastric cancer[2]. This study was designed to compare in detail different types of esophagogastrostomy.

Proximal gastrectomy impacts severely on physical and mental health, and has highly negative consequences for QOL at 6 and 24 mo. Although postoperative QOL has been shown to be important in the surgical literature[3], there have only been a few studies on QOL in patients after proximal gastrectomy. For patients undergoing oncological surgery, QOL is generally accepted as an important outcome parameter, in addition to long-term survival, mortality, and complication rates. In order to provide patients with improved postoperative QOL, many surgeons seek the optimal surgical methods. Compared with total gastrectomy, the advantages of proximal gastrectomy were shorter operation times, less blood loss and convenience of procedure[4]. No previous studies have assessed different types of esophagogastrostomy in terms of QOL.

The aim of this study was to assess outcome in terms of QOL in patients after proximal gastrectomy, by comparing three types of esophagogastrostomy, in order to find the optimal reconstruction method that offers the optimal postoperative QOL at 6 and 24 mo.

Between January 2002 and December 2005, 195 patients with proximal gastric cancer were treated at the Department of Surgical Oncology, First Affiliated Hospital of China Medical University, Shenyang, China. Only 149 patients who were in the present prospective randomized study met the following study criteria: (1) underwent curative resection with lymph node dissection; (2) had no history of other organ malignancies; and (3) had more than 15 lymph nodes retrieved and confirmed by a specialist pathologist. The exclusion criteria included: (1) age > 80 years; (2) renal, pulmonary, or heart failure; (3) undergoing palliative surgery; (4) tumor recurrence during the survey; (5) preoperative or postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy; and (6) albumin level < 3.5 g/dL and a lymphocyte count lower than 1000 lymphocytes/mm3 in peripheral blood.

The standard surgical procedure and extent of lymph node dissection were defined according to the recommendations of the Japanese Research Society for the Study of Gastric Cancer[5]. All patients were treated with stapler suture for digestive tract reconstruction after malignancy removal during the primary surgical procedure. Esophagogastrostomy was performed by using a mechanical stapler (Ethicon Endo-Surgery, USA). In addition, a row of external seromuscular sutures with interrupted absorbable stitches was also performed.

All patients underwent esophagogastrostomy with curative intent and were randomized using a table of random numbers into three groups. To perform esophagogastric anterior wall end-to-side anastomosis combined with pyloroplasty (EA procedure), the anastomosis should be 2-3 cm under the gastric incision line, to guarantee the blood supply of the anastomosis. The stapler inserted into the remnant stomach through the gastric antrum and the center rod of the circular stapler was pierced through the center of the anterior wall, and during this stapling, an ischemic area is not created at all. The esophagus was then anastomosed to the anterior wall in the center of the remnant stomach. A 3-4 mm wide serosal surface of the anterior wall of the remnant stomach strapped the esophagus circularly. After completion of esophagogastrostomy, the left end of the gastric stump was fixed to the diaphragm. Furthermore, the pyloroplasty was done in the standard manner with interrupted sutures[6–8]. To perform esophagogastric posterior wall end-to-side anastomosis (EP procedure), the stapler that was inserted into the remnant stomach through the anterior wall, and the center rod of the circular stapler was pierced through the center of the posterior wall. To perform esophagogastric end-to-end anastomosis (EE procedure), the center rod of the circular stapler was pierced through the left end of the staple line of the stomach.

Functional outcome was assessed using a 24-item survey designed to assess treatment-specific symptoms, largely gastrointestinal function[9]. The questions were scaled according to the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group[10]. The Spitzer QOL index, which reflects the patient’s postoperative health perception[11], is a global health assessment with a valid questionnaire that includes five items rated on a three-point scale: activity, daily living, health, support of family and friends, and outlook. The answers were analyzed in a quantitative fashion using a scoring system: the scores ranged from 0 (unsatisfactory result with severe symptoms) to 2 (excellent result with no symptoms); low scores reflected more symptoms. Questionnaires were administered at 6 and 24 mo postoperatively and annually thereafter until tumor recurrence. Average scores were calculated for each question. The Ethics Committee approved the study protocol and informed consent was obtained from each patient. Patients were closely followed after surgery until December 2007. The median follow-up duration was 42.5 mo (range, 9-67 mo). At the time of the last follow-up, 115 patients (77.2%) were alive, no patient was lost to follow-up, and 34 (22.8%) had died from recurrence or other causes.

All statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Package for Social Science software for Windows version 13.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Data were expressed as mean ± SD. Categorical data were compared using the Kruskal-Wallis test, Mann-Whitney U test, analysis of variance and χ2 test. P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. For calculation of survival rate, the Kaplan-Meier method was used, and compared using the log-rank test.

Table 1 summarizes clinicopathological factors in relation to the three groups. There were 95 (65%) male and 54 (35%) female patients, with a mean age of 61.5 ± 6.5 years. There were no significant differences in the clinicopathological features such as sex, age, tumor size, histological type, Lauren’s classification, lymph node status, or lymphovascular invasion among the three groups.

| Clinicopathological factors | EA group (54) | EP group (45) | EE group (50) | P |

| Age (yr) | 62.5 ± 5.4 | 56.6 ± 7.6 | 65.1 ± 8.6 | 0.668 |

| Gender | 0.775 | |||

| Male | 36 | 29 | 30 | |

| Female | 18 | 16 | 20 | |

| Tumor size (cm) | 4.6 ± 1.6 | 5.0 ± 1.7 | 4.8 ± 1.3 | 0.963 |

| Histological type | 0.993 | |||

| Well-differentiated | 18 | 15 | 17 | |

| Moderately differentiated | 20 | 17 | 19 | |

| Poorly differentiated | 10 | 9 | 8 | |

| Signet ring cell type | 6 | 4 | 6 | |

| Lauren’s classification | 0.978 | |||

| Intestinal | 30 | 24 | 27 | |

| Diffuse | 18 | 16 | 17 | |

| Mixed | 6 | 5 | 6 | |

| Lymph node status | 0.989 | |||

| Negative | 38 | 34 | 36 | |

| Positive | 16 | 11 | 14 | |

| Lymphovascular invasion | 0.989 | |||

| Negative | 45 | 38 | 42 | |

| Positive | 9 | 7 | 8 | |

| Stage | 0.788 | |||

| I | 17 | 16 | 18 | |

| II | 21 | 17 | 20 | |

| IIIa | 11 | 7 | 9 | |

| IIIb | 5 | 5 | 3 |

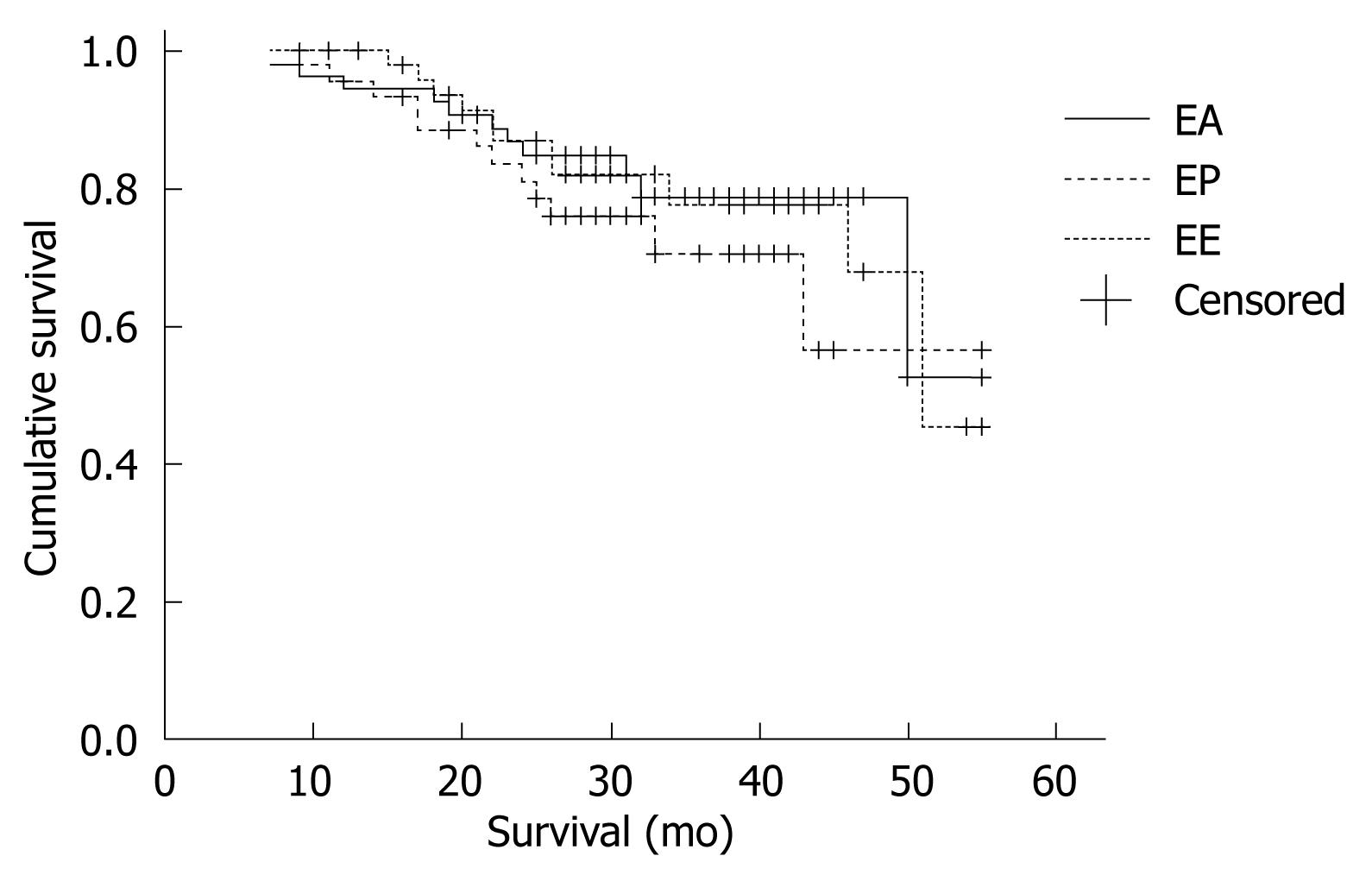

The survival time was defined as the time from diagnosis until last contact, date of death, or the date used as a cutoff for the follow-up database, in which case the survival information was censored. The 2-year survival rate was 79.6%, 73.3% and 78.0% for the EA, EP and the EE group, respectively. The survival rates were similar in all treatment groups (P = 0.713, Figure 1). The surgical results did not differ among the three groups (Table 2).

| Surgical factors | EA group | EP group | P | EA group | EE group | P | EP group | EE group | P |

| Additional organ resection | 0.609 | 0.831 | 0.766 | ||||||

| Splenectomy | 8 | 7 | 0.919 | 8 | 7 | 0.906 | 7 | 7 | 0.832 |

| Splenopancreatectomy | 1 | 2 | 0.456 | 1 | 2 | 0.515 | 2 | 2 | 0.915 |

| Transverse mesocolectomy | 2 | 2 | 0.853 | 2 | 3 | 0.586 | 2 | 3 | 0.736 |

| Wedge liver resection | 1 | 1 | 0.897 | 1 | 2 | 0.515 | 1 | 2 | 0.623 |

| Margin status | 0.670 | 0.938 | 0.623 | ||||||

| Negative | 52 | 44 | 52 | 48 | 44 | 48 | |||

| Positive | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | |||

| Lymph node dissection | 0.902 | 0.804 | 0.721 | ||||||

| D1 | 15 | 12 | 15 | 14 | 12 | 14 | |||

| ≥ D2 | 39 | 33 | 39 | 36 | 33 | 36 | |||

| No. of lymph nodes | 29.6 ± 7.6 | 28.5 ± 6.8 | 0.524 | 29.6 ± 7.6 | 30.1 ± 7.2 | 0.857 | 28.5 ± 6.8 | 30.1 ± 7.2 | 0.657 |

| Operating time (min) | 166.3 ± 47.5 | 156.8 ± 53.1 | 0.758 | 166.3 ± 47.5 | 149.7 ± 61.2 | 0.564 | 156.8 ± 53.1 | 149.7 ± 61.2 | 0.265 |

| Blood loss (mL) | 263.4 ± 112.6 | 267.3 ± 121.6 | 0.273 | 263.4 ± 112.6 | 276.9 ± 135.5 | 0.647 | 267.3 ± 121.6 | 276.9 ± 135.5 | 0.798 |

| Postoperative stay (d) | 18.0 ± 5.7 | 20.9 ± 7.8 | 0.874 | 18.0 ± 5.7 | 19.0 ± 5.7 | 0.953 | 20.9 ± 7.8 | 19.0 ± 5.7 | 0.849 |

| Postoperative complications | 12 | 11 | 0.795 | 12 | 13 | 0.654 | 11 | 13 | 0.862 |

| Mortality | 0 | 1 | 0.273 | 0 | 1 | 0.299 | 1 | 1 | 0.940 |

The evaluation scores for eating time were 1.83, 1.58 and 1.42 in EA, EP and the EE groups, respectively. The EA group had a significantly shorter eating time than the EP group (1.83 vs 1.58, P = 0.005) and the EE group (1.83 vs 1.42, P = 0.000).

The evaluation scores for dietary volume were 1.20, 0.60 and 0.58 in the EA, EP and the EE groups, respectively. The EA group had a significantly better dietary volume than the EP group (1.20 vs 0.60, P = 0.000) and the EE group (1.20 vs 0.58, P = 0.000).

The evaluation scores for heartburn or belching were 1.37, 0.73 and 0.80 in the EA, EP and the EE groups, respectively. The EA group had significantly less heartburn or belching than the EP group (1.37 vs 0.73, P = 0.000) and the EE group (1.37 vs 0.80, P = 0.000) (Table 3).

| Question | EA group | EP group | P | EA group | EE group | P | EP group | EE group | P |

| Frequency of eating | 0.76 ± 0.799 | 0.80 ± 0.968 | 0.957 | 0.76 ± 0.799 | 0.78 ± 0.616 | 0.664 | 0.80 ± 0.968 | 0.78 ± 0.616 | 0.698 |

| Eating time | 1.83 ± 0.376 | 1.58 ± 0.499 | 0.005a | 1.83 ± 0.376 | 1.42 ± 0.642 | 0.000a | 1.58 ± 0.499 | 1.42 ± 0.642 | 0.287 |

| Consistency of food | 0.76 ± 0.845 | 0.71 ± 0.815 | 0.803 | 0.76 ± 0.845 | 0.84 ± 0.792 | 0.543 | 0.71 ± 0.815 | 0.84 ± 0.792 | 0.391 |

| Volume of food | 1.20 ± 0.810 | 0.60 ± 0.780 | 0.000a | 1.20 ± 0.810 | 0.58 ± 0.702 | 0.000a | 0.60 ± 0.780 | 0.58 ± 0.702 | 0.950 |

| Body weight | 0.80 ± 0.711 | 0.78 ± 0.636 | 0.969 | 0.80 ± 0.711 | 0.66 ± 0.848 | 0.221 | 0.78 ± 0.636 | 0.66 ± 0.848 | 0.225 |

| Appetite | 1.13 ± 0.674 | 0.87 ± 0.968 | 0.120 | 1.13 ± 0.674 | 1.16 ± 0.817 | 0.724 | 0.87 ± 0.968 | 1.16 ± 0.817 | 0.118 |

| Difficulty swallowing | 1.56 ± 0.664 | 1.42 ± 0.723 | 0.333 | 1.56 ± 0.664 | 1.54 ± 0.734 | 0.898 | 1.42 ± 0.723 | 1.54 ± 0.734 | 0.308 |

| Diarrhea | 1.83 ± 0.376 | 1.69 ± 0.733 | 0.843 | 1.83 ± 0.376 | 1.78 ± 0.582 | 0.852 | 1.69 ± 0.733 | 1.78 ± 0.582 | 0.734 |

| Heartburn or belch | 1.37 ± 0.708 | 0.73 ± 0.863 | 0.000a | 1.37 ± 0.708 | 0.80 ± 0.756 | 0.000a | 0.73 ± 0.863 | 0.80 ± 0.756 | 0.547 |

| Postprandial discomfort | 1.46 ± 0.693 | 1.24 ± 0.957 | 0.433 | 1.46 ± 0.693 | 1.52 ± 0.677 | 0.646 | 1.24 ± 0.957 | 1.52 ± 0.677 | 0.267 |

| Abdominal pain | 1.54 ± 0.770 | 1.49 ± 0.787 | 0.721 | 1.54 ± 0.770 | 1.60 ± 0.495 | 0.698 | 1.49 ± 0.787 | 1.60 ± 0.495 | 0.965 |

| Vomiting | 1.48 ± 0.771 | 1.49 ± 0.757 | 0.993 | 1.48 ± 0.771 | 1.68 ± 0.471 | 0.368 | 1.49 ± 0.757 | 1.68 ± 0.471 | 0.389 |

| General fatigue | 1.80 ± 0.528 | 1.82 ± 0.387 | 0.792 | 1.80 ± 0.528 | 1.92 ± 0.274 | 0.250 | 1.82 ± 0.387 | 1.92 ± 0.274 | 0.154 |

| Dizziness | 1.80 ± 0.562 | 1.89 ± 0.318 | 0.687 | 1.80 ± 0.562 | 1.74 ± 0.600 | 0.507 | 1.89 ± 0.318 | 1.74 ± 0.600 | 0.289 |

| Intestinal obstruction | 1.65 ± 0.555 | 1.56 ± 0.693 | 0.669 | 1.65 ± 0.555 | 1.66 ± 0.519 | 0.997 | 1.56 ± 0.693 | 1.66 ± 0.519 | 0.667 |

| Performance status | 1.54 ± 0.719 | 1.64 ± 0.743 | 0.240 | 1.54 ± 0.719 | 1.58 ± 0.642 | 0.910 | 1.64 ± 0.743 | 1.58 ± 0.642 | 0.269 |

| Early dumping syndrome | 1.54 ± 0.665 | 1.40 ± 0.720 | 0.319 | 1.54 ± 0.665 | 1.42 ± 0.673 | 0.307 | 1.40 ± 0.720 | 1.42 ± 0.673 | 0.970 |

| Late dumping syndrome | 1.78 ± 0.502 | 1.73 ± 0.688 | 0.669 | 1.78 ± 0.502 | 1.86 ± 0.452 | 0.241 | 1.73 ± 0.688 | 1.86 ± 0.452 | 0.532 |

| Physical condition | 1.67 ± 0.673 | 1.80 ± 0.548 | 0.258 | 1.67 ± 0.673 | 1.76 ± 0.517 | 0.661 | 1.80 ± 0.548 | 1.76 ± 0.517 | 0.450 |

| Wound pain, present | 1.57 ± 0.690 | 1.53 ± 0.815 | 0.874 | 1.57 ± 0.690 | 1.62 ± 0.490 | 0.809 | 1.53 ± 0.815 | 1.62 ± 0.490 | 0.704 |

| Wound pain, postoperative | 1.07 ± 0.866 | 1.18 ± 0.716 | 0.600 | 1.07 ± 0.866 | 1.22 ± 0.764 | 0.413 | 1.18 ± 0.716 | 1.22 ± 0.764 | 0.727 |

| Satisfaction with operation | 1.57 ± 0.690 | 1.69 ± 0.557 | 0.495 | 1.57 ± 0.690 | 1.66 ± 0.688 | 0.357 | 1.69 ± 0.557 | 1.66 ± 0.688 | 0.784 |

| Recommendation to others | 1.41 ± 0.714 | 1.29 ± 0.787 | 0.484 | 1.41 ± 0.714 | 1.46 ± 0.706 | 0.680 | 1.29 ± 0.787 | 1.46 ± 0.706 | 0.290 |

| Mood or feeling | 1.67 ± 0.673 | 1.67 ± 0.707 | 0.859 | 1.67 ± 0.673 | 1.70 ± 0.463 | 0.610 | 1.67 ± 0.707 | 1.70 ± 0.463 | 0.507 |

| Total | 1.45 ± 0.748 | 1.36 ± 0.825 | 0.059 | 1.45 ± 0.748 | 1.42 ± 0.743 | 0.147 | 1.36 ± 0.825 | 1.42 ± 0.743 | 0.389 |

Most parameters tended to be normalized sooner after surgery in the EA group.

The evaluation scores for body weight were 1.48, 1.13 and 1.14 in the EA, EP and the EE groups, respectively. The EA group had significantly better body weight recovery than the EP group (1.48 vs 1.13, P = 0.005) and the EE group (1.48 vs 1.14, P = 0.030).

The evaluation scores for heartburn or belching were 1.78, 1.73 and 1.38 in the EA, EP and the EE groups, respectively. The EA group (1.78 vs 1.38, P = 0.005) and the EP group (1.73 vs 1.38, P = 0.023) had significantly less heartburn or belching than the EE group.

The evaluation scores for postprandial discomfort were 1.69, 1.07 and 1.22 in the EA, EP and the EE groups, respectively. The EA group showed less postprandial discomfort than the EP group (1.69 vs 1.07, P = 0.000) and the EE group (1.69 vs 1.22, P = 0.001) (Table 4).

| Question | EA group | EP group | P | EA group | EE group | P | EP group | EE group | P |

| Frequency of eating | 1.67 ± 0.583 | 1.62 ± 0.614 | 0.711 | 1.67 ± 0.583 | 1.70 ± 0.580 | 0.693 | 1.62 ± 0.614 | 1.70 ± 0.580 | 0.461 |

| Eating time | 1.85 ± 0.359 | 1.78 ± 0.471 | 0.472 | 1.85 ± 0.359 | 1.88 ± 0.328 | 0.676 | 1.78 ± 0.471 | 1.88 ± 0.328 | 0.273 |

| Consistency of food | 1.65 ± 0.619 | 1.73 ± 0.618 | 0.306 | 1.65 ± 0.619 | 1.80 ± 0.535 | 0.105 | 1.73 ± 0.618 | 1.80 ± 0.535 | 0.601 |

| Volume of food | 1.69 ± 0.639 | 1.62 ± 0.684 | 0.613 | 1.69 ± 0.639 | 1.70 ± 0.580 | 0.915 | 1.62 ± 0.684 | 1.70 ± 0.580 | 0.680 |

| Body weight | 1.48 ± 0.637 | 1.13 ± 0.625 | 0.005a | 1.48 ± 0.637 | 1.14 ± 0.047 | 0.030a | 1.13 ± 0.625 | 1.14 ± 0.047 | 0.837 |

| Appetite | 1.57 ± 0.662 | 1.78 ± 0.560 | 0.056 | 1.57 ± 0.662 | 1.70 ± 0.580 | 0.290 | 1.78 ± 0.560 | 1.70 ± 0.580 | 0.349 |

| Difficulty swallowing | 1.52 ± 0.720 | 1.49 ± 0.787 | 0.116 | 1.52 ± 0.720 | 1.74 ± 0.600 | 0.059 | 1.49 ± 0.787 | 1.74 ± 0.600 | 0.136 |

| Diarrhea | 1.87 ± 0.339 | 1.80 ± 0.505 | 0.654 | 1.87 ± 0.339 | 1.82 ± 0.523 | 0.977 | 1.80 ± 0.505 | 1.82 ± 0.523 | 0.658 |

| Heartburn or belch | 1.78 ± 0.502 | 1.73 ± 0.539 | 0.651 | 1.78 ± 0.502 | 1.38 ± 0.805 | 0.005a | 1.73 ± 0.539 | 1.38 ± 0.805 | 0.023a |

| Postprandial discomfort | 1.69 ± 0.609 | 1.07 ± 0.915 | 0.000a | 1.69 ± 0.609 | 1.22 ± 0.790 | 0.001a | 1.07 ± 0.915 | 1.22 ± 0.790 | 0.445 |

| Abdominal pain | 1.65 ± 0.649 | 1.60 ± 0.720 | 0.848 | 1.65 ± 0.649 | 1.70 ± 0.505 | 0.968 | 1.60 ± 0.720 | 1.70 ± 0.505 | 0.841 |

| Vomiting | 1.69 ± 0.577 | 1.67 ± 0.674 | 0.814 | 1.69 ± 0.577 | 1.70 ± 0.463 | 0.786 | 1.67 ± 0.674 | 1.70 ± 0.463 | 0.628 |

| General fatigue | 1.76 ± 0.581 | 1.78 ± 0.420 | 0.626 | 1.76 ± 0.581 | 1.84 ± 0.370 | 0.800 | 1.78 ± 0.420 | 1.84 ± 0.370 | 0.442 |

| Dizziness | 1.83 ± 0.505 | 1.93 ± 0.252 | 0.410 | 1.83 ± 0.505 | 1.80 ± 0.535 | 0.671 | 1.93 ± 0.252 | 1.80 ± 0.535 | 0.223 |

| Intestinal obstruction | 1.78 ± 0.502 | 1.64 ± 0.679 | 0.396 | 1.78 ± 0.502 | 1.68 ± 0.513 | 0.204 | 1.64 ± 0.679 | 1.68 ± 0.513 | 0.771 |

| Performance status | 1.63 ± 0.653 | 1.71 ± 0.661 | 0.322 | 1.63 ± 0.653 | 1.70 ± 0.463 | 0.951 | 1.71 ± 0.661 | 1.70 ± 0.463 | 0.318 |

| Early dumping syndrome | 1.70 ± 0.603 | 1.62 ± 0.650 | 0.465 | 1.70 ± 0.603 | 1.60 ± 0.728 | 0.560 | 1.62 ± 0.650 | 1.60 ± 0.728 | 0.901 |

| Late dumping syndrome | 1.70 ± 0.537 | 1.73 ± 0.580 | 0.567 | 1.70 ± 0.537 | 1.72 ± 0.479 | 0.966 | 1.73 ± 0.580 | 1.72 ± 0.479 | 0.594 |

| Physical condition | 1.72 ± 0.627 | 1.64 ± 0.712 | 0.616 | 1.72 ± 0.627 | 1.76 ± 0.476 | 0.820 | 1.64 ± 0.712 | 1.76 ± 0.476 | 0.753 |

| Wound pain, present | 1.83 ± 0.423 | 1.73 ± 0.580 | 0.450 | 1.83 ± 0.423 | 1.78 ± 0.465 | 0.494 | 1.73 ± 0.580 | 1.78 ± 0.465 | 0.910 |

| Wound pain, postoperative | 1.07 ± 0.866 | 1.18 ± 0.716 | 0.600 | 1.07 ± 0.866 | 1.22 ± 0.764 | 0.413 | 1.18 ± 0.716 | 1.22 ± 0.764 | 0.727 |

| Satisfaction with operation | 1.72 ± 0.596 | 1.76 ± 0.484 | 0.937 | 1.72 ± 0.596 | 1.72 ± 0536 | 0.746 | 1.76 ± 0.484 | 1.72 ± 0.536 | 0.807 |

| Recommendation to others | 1.59 ± 0.567 | 1.42 ± 0.690 | 0.239 | 1.59 ± 0.567 | 1.54 ± 0.646 | 0.795 | 1.42 ± 0.690 | 1.54 ± 0.646 | 0.382 |

| Mood or feeling | 1.63 ± 0.708 | 1.71 ± 0.695 | 0.371 | 1.63 ± 0.708 | 1.66 ± 0.519 | 0.634 | 1.71 ± 0.695 | 1.66 ± 0.519 | 0.162 |

| Total | 1.67 ± 0.612 | 1.61 ± 0.663 | 0.116 | 1.67 ± 0.612 | 1.65 ± 0.609 | 0.150 | 1.61 ± 0.663 | 1.65 ± 0.609 | 0.532 |

When the QOL scores between 6 and 24 mo were compared in the same group, the frequency of eating, food consistency, food volume, body weight, appetite, and heartburn or belching at 24 mo were all improved significantly in each group compared with at 6 mo. The eating time at 24 mo was significantly shorter than at 6 mo in the EP and EE group (EP, P = 0.031 and EE, P = 0.000). The postprandial discomfort at 6 mo was significantly less than at 24 mo in the EE group (P = 0.048). Wound pain at 24 mo was significantly less than at 6 mo in the EA group (P = 0.031).

It can be seen that, as postoperative time progresses, most symptoms improved, especially in terms eating frequency, food consistency, food volume, body weight, appetite, and heartburn or belching, and the total scores at 24 mo were all improved significantly compared with at 6 mo in the EA (P = 0.015), EP (P = 0.007) and EE (P = 0.011) groups (Table 5).

| Question | EA group | P | EP group | P | EE group | P | |||

| 6 mo | 24 mo | 6 mo | 24 mo | 6 mo | 24 mo | ||||

| Frequency of eating | 0.76 ± 0.799 | 1.67 ± 0.583 | 0.000a | 0.80 ± 0.968 | 1.62 ± 0.614 | 0.000a | 0.78 ± 0.616 | 1.70 ± 0.580 | 0.000a |

| Eating time | 1.83 ± 0.376 | 1.85 ± 0.359 | 0.793 | 1.58 ± 0.499 | 1.78 ± 0.471 | 0.031a | 1.42 ± 0.642 | 1.88 ± 0.328 | 0.000a |

| Consistency of food | 0.76 ± 0.845 | 1.65 ± 0.619 | 0.000a | 0.71 ± 0.815 | 1.73 ± 0.618 | 0.000a | 0.84 ± 0.792 | 1.80 ± 0.535 | 0.000a |

| Volume of food | 1.20 ± 0.810 | 1.69 ± 0.639 | 0.001a | 0.60 ± 0.780 | 1.62 ± 0.684 | 0.000a | 0.58 ± 0.702 | 1.70 ± 0.580 | 0.000a |

| Body weight | 0.80 ± 0.711 | 1.48 ± 0.637 | 0.000a | 0.78 ± 0.636 | 1.13 ± 0.625 | 0.010a | 0.66 ± 0.848 | 1.14 ± 0.047 | 0.004a |

| Appetite | 1.13 ± 0.674 | 1.57 ± 0.662 | 0.000a | 0.87 ± 0.968 | 1.78 ± 0.560 | 0.000a | 1.16 ± 0.817 | 1.70 ± 0.580 | 0.000a |

| Difficulty swallowing | 1.56 ± 0.664 | 1.52 ± 0.720 | 0.890 | 1.42 ± 0.723 | 1.49 ± 0.787 | 0.431 | 1.54 ± 0.734 | 1.74 ± 0.600 | 0.112 |

| Diarrhea | 1.83 ± 0.376 | 1.87 ± 0.339 | 0.590 | 1.69 ± 0.733 | 1.80 ± 0.505 | 0.823 | 1.78 ± 0.582 | 1.82 ± 0.523 | 0.754 |

| Heartburn or belch | 1.37 ± 0.708 | 1.78 ± 0.502 | 0.001a | 0.73 ± 0.863 | 1.73 ± 0.539 | 0.000a | 0.80 ± 0.756 | 1.38 ± 0.805 | 0.000a |

| Postprandial discomfort | 1.46 ± 0.693 | 1.69 ± 0.609 | 0.052 | 1.24 ± 0.957 | 1.07 ± 0.915 | 0.321 | 1.52 ± 0.677 | 1.22 ± 0.790 | 0.048a |

| Abdominal pain | 1.54 ± 0.770 | 1.65 ± 0.649 | 0.547 | 1.49 ± 0.787 | 1.60 ± 0.720 | 0.481 | 1.60 ± 0.495 | 1.70 ± 0.505 | 0.241 |

| Vomiting | 1.48 ± 0.771 | 1.69 ± 0.577 | 0.199 | 1.49 ± 0.757 | 1.67 ± 0.674 | 0.188 | 1.68 ± 0.471 | 1.70 ± 0.463 | 0.830 |

| General fatigue | 1.80 ± 0.528 | 1.76 ± 0.581 | 0.775 | 1.82 ± 0.387 | 1.78 ± 0.420 | 0.600 | 1.92 ± 0.274 | 1.84 ± 0.370 | 0.221 |

| Dizziness | 1.80 ± 0.562 | 1.83 ± 0.505 | 0.757 | 1.89 ± 0.318 | 1.93 ± 0.252 | 0.461 | 1.74 ± 0.600 | 1.80 ± 0.535 | 0.585 |

| Intestinal obstruction | 1.65 ± 0.555 | 1.78 ± 0.502 | 0.138 | 1.56 ± 0.693 | 1.64 ± 0.679 | 0.417 | 1.66 ± 0.519 | 1.68 ± 0.513 | 0.834 |

| Performance status | 1.54 ± 0.719 | 1.63 ± 0.653 | 0.502 | 1.64 ± 0.743 | 1.71 ± 0.661 | 0.740 | 1.58 ± 0.642 | 1.70 ± 0.463 | 0.498 |

| Early dumping syndrome | 1.54 ± 0.665 | 1.70 ± 0.603 | 0.114 | 1.40 ± 0.720 | 1.62 ± 0.650 | 0.097 | 1.42 ± 0.673 | 1.60 ± 0.728 | 0.072 |

| Late dumping syndrome | 1.78 ± 0.502 | 1.70 ± 0.537 | 0.377 | 1.73 ± 0.688 | 1.73 ± 0.580 | 0.538 | 1.86 ± 0.452 | 1.72 ± 0.479 | 0.050 |

| Physical condition | 1.67 ± 0.673 | 1.72 ± 0.627 | 0.637 | 1.80 ± 0.548 | 1.64 ± 0.712 | 0.259 | 1.76 ± 0.517 | 1.76 ± 0.476 | 0.853 |

| Wound pain, present | 1.57 ± 0.690 | 1.83 ± 0.423 | 0.031a | 1.53 ± 0.815 | 1.73 ± 0.580 | 0.326 | 1.62 ± 0.490 | 1.78 ± 0.465 | 0.059 |

| Wound pain, postoperative | 1.07 ± 0.866 | 1.07 ± 0.866 | 1.000 | 1.18 ± 0.716 | 1.18 ± 0.716 | 1.000 | 1.22 ± 0.764 | 1.22 ± 0.764 | 1.000 |

| Satisfaction with operation | 1.57 ± 0.690 | 1.72 ± 0.596 | 0.197 | 1.69 ± 0.557 | 1.76 ± 0.484 | 0.597 | 1.66 ± 0.688 | 1.72 ± 0536 | 0.599 |

| Recommendation to others | 1.41 ± 0.714 | 1.59 ± 0.567 | 0.206 | 1.29 ± 0.787 | 1.42 ± 0.690 | 0.467 | 1.46 ± 0.706 | 1.54 ± 0.646 | 0.606 |

| Mood or feeling | 1.67 ± 0.673 | 1.63 ± 0.708 | 0.802 | 1.67 ± 0.707 | 1.71 ± 0.695 | 0.636 | 1.70 ± 0.463 | 1.66 ± 0.519 | 0.780 |

| Total | 1.45 ± 0.748 | 1.67 ± 0.612 | 0.015a | 1.36 ± 0.825 | 1.61 ± 0.663 | 0.007a | 1.42 ± 0.743 | 1.65 ± 0.609 | 0.011a |

The data from the Spitzer index (Tables 6 and 7) showed that after all the postoperative and oncological problems were solved, proximal gastrectomy was quite compatible with normal life. From the results of Spitzer index evaluation, we also concluded that patients after proximal gastrectomy may have a nearly normal life with activity and daily living at 6 and 24 mo.

| Factors | EA group | EP group | P | EA group | EE group | P | EP group | EE group | P |

| 6 mo | |||||||||

| Activity | 1.74 ± 0.556 | 1.80 ± 0.548 | 0.403 | 1.74 ± 0.556 | 1.76 ± 0.476 | 0.920 | 1.80 ± 0.548 | 1.76 ± 0.476 | 0.347 |

| Daily living | 1.85 ± 0.359 | 1.78 ± 0.420 | 0.344 | 1.85 ± 0.359 | 1.84 ± 0.422 | 0.940 | 1.78 ± 0.420 | 1.84 ± 0.422 | 0.326 |

| Health | 1.65 ± 0.588 | 1.62 ± 0.535 | 0.630 | 1.65 ± 0.588 | 1.76 ± 0.517 | 0.266 | 1.62 ± 0.535 | 1.76 ± 0.517 | 0.115 |

| Support | 1.78 ± 0.462 | 1.71 ± 0.506 | 0.467 | 1.78 ± 0.462 | 1.74 ± 0.487 | 0.661 | 1.71 ± 0.506 | 1.74 ± 0.487 | 0.767 |

| Outlook | 1.76 ± 0.473 | 1.73 ± 0.539 | 0.946 | 1.76 ± 0.473 | 1.78 ± 0.465 | 0.790 | 1.73 ± 0.539 | 1.78 ± 0.465 | 0.752 |

| 24 mo | |||||||||

| Activity | 1.72 ± 0.492 | 1.71 ± 0.506 | 0.835 | 1.72 ± 0.492 | 1.82 ± 0.388 | 0.674 | 1.71 ± 0.506 | 1.82 ± 0.388 | 0.802 |

| Daily living | 1.87 ± 0.339 | 1.84 ± 0.367 | 0.714 | 1.87 ± 0.339 | 1.90 ± 0.364 | 0.724 | 1.84 ± 0.367 | 1.90 ± 0.364 | 0.273 |

| Health | 1.76 ± 0.473 | 1.76 ± 0.484 | 0.352 | 1.76 ± 0.473 | 1.90 ± 0.303 | 0.557 | 1.76 ± 0.484 | 1.90 ± 0.303 | 0.947 |

| Support | 1.80 ± 0.451 | 1.80 ± 0.457 | 0.367 | 1.80 ± 0.451 | 1.84 ± 0.370 | 0.839 | 1.80 ± 0.457 | 1.84 ± 0.370 | 0.583 |

| Outlook | 1.83 ± 0.376 | 1.76 ± 0.529 | 0.892 | 1.83 ± 0.376 | 1.70 ± 0.614 | 0.692 | 1.76 ± 0.529 | 1.70 ± 0.614 | 0.793 |

| Factors | EA group | P | EP group | P | EE group | P | |||

| 6 mo | 24 mo | 6 mo | 24 mo | 6 mo | 24 mo | ||||

| Activity | 1.74 ± 0.556 | 1.72 ± 0.492 | 0.583 | 1.80 ± 0.548 | 1.71 ± 0.506 | 0.164 | 1.76 ± 0.476 | 1.82 ± 0.388 | 0.588 |

| Daily living | 1.85 ± 0.359 | 1.87 ± 0.339 | 0.782 | 1.78 ± 0.420 | 1.84 ± 0.367 | 0.422 | 1.84 ± 0.422 | 1.90 ± 0.364 | 0.350 |

| Health | 1.65 ± 0.588 | 1.76 ± 0.473 | 0.342 | 1.62 ± 0.535 | 1.76 ± 0.484 | 0.177 | 1.76 ± 0.517 | 1.90 ± 0.303 | 0.148 |

| Support | 1.78 ± 0.462 | 1.80 ± 0.451 | 0.813 | 1.71 ± 0.506 | 1.80 ± 0.457 | 0.325 | 1.74 ± 0.487 | 1.84 ± 0.370 | 0.301 |

| Outlook | 1.76 ± 0.473 | 1.83 ± 0.376 | 0.444 | 1.73 ± 0.539 | 1.76 ± 0.529 | 0.807 | 1.78 ± 0.465 | 1.70 ± 0.614 | 0.701 |

The choice of reconstruction method after proximal gastrectomy remains a controversial issue. Previously, several studies have found no difference in the 5-year survival among patients with proximal gastrectomy and those with total gastrectomy[67]. Proximal gastrectomy for early gastric cancer in the upper third of the stomach is an appropriate operation in terms of radical treatment and safety. Proximal gastrectomy was introduced to improve performance status of patients and minimize late postoperative complications such as reflux esophagitis[812–15].

It is well known that moderate malnutrition is often associated with gastric cancer surgery[16], and that esophagogastrostomy reconstruction is more favorable to the natural food passage of the duodenum than esophagojejunostomy. It has been shown that independent prognostic factors such as ensuring radical cure, maintaining food passage in the duodenum, and less excision of the stomach, are very important for postoperative QOL[1718]. A high incidence of reflux symptoms after simple esophagogastrostomy has prompted the development of several novel reconstructions to prevent reflux[1219–21]. Previous reports have shown that proximal gastrectomy is more likely to produce complications such as heartburn and poor appetite, and worsen nutritional status compared to other types of gastrectomy[22]. To prevent or minimize postgastrectomy complications, proximal gastrectomy with an interposed jejunal pouch has been advocated as an organ-preserving strategy to improve QOL[1323–25]. However, there some studies have shown that patients with an interposed jejunal pouch need a second operation because of food stasis or disordered gastric emptying, and the length of the jejunal pouch is still under discussion[26–28].

To avoid postoperative symptoms, there is no consensus on the need for pyloroplasty after proximal gastrectomy. Our study suggested that pyloroplasty improved gastric emptying and decreased stomach stasis. Other studies have shown that pyloroplasty might significantly relieve gastric distention and speed up gastric emptying[2930]. Our data showed that most patients suffered from heartburn and postprandial abdominal fullness after proximal gastrectomy. However, patients in the EA group showed significantly less heartburn and postprandial abdominal fullness compared to the other groups. Pyloroplasty as a draining procedure helps the patient have fewer complications such as gastric distention, nausea and vomiting, and promotes faster gastric emptying[31]. Patients with pyloroplasty may recover 80% of the dietary volume in the short term after surgery. In addition, our study found that pyloroplasty also helped to recover or improve body weight in the long term, postoperatively. Our study suggested that patients treated with an EA procedure had a better QOL than the other groups, however, this was correlated with pyloroplasty and promoted gastric emptying to some extent.

The EA procedure decreased the postoperative reflux symptoms in the long term. This simple and safe technique does not result in postgastrectomy syndrome. The mortality rate was zero and the absence of early postoperative complications highlighted the safety of this procedure. Thus, proximal gastrectomy reconstruction by EA provided excellent clinical results in patients with proximal gastric cancer.

After proximal gastrectomy, body weight decreased (approximately 5-10 kg) below baseline after the first few postoperative months, and later, the weight stabilized if there were no tumor recurrence, and recovered slowly almost to baseline. Our study showed that even 2 years postoperatively, the EA group showed a significantly better recovered or improved body weight than the other groups. Seven patients in the EA group recovered 100%, and more than two-thirds of patients maintained at least 85% of baseline weight 2 years after surgery. In summary, the EA procedure benefited the patients with upper third gastric cancer in terms of body weight.

Some patients after proximal gastrectomy suffered from reduced meal size, due to microgastria. To avoid microgastria, the esophagogastrostomy performed by the EE procedure may help to maintain the longest distance from the pylorus to the anastomotic stoma. The center rod of the circular stapler is pierced through the left end of the staple line of the stomach. The longest distance from the pylorus to the esophagogastrostomy site can be found in this position. The longer distance will reduce microgastria and also decrease the tension of the stoma.

There were some limitations in our study. Firstly, the patients were not at the same stage in terms of their gastric cancer; 32.2% were early stage patients. Although QOL in the EA group was better than in the other two groups, whether QOL in the EA group is better than that for other reconstruction methods, or if it reaches the threshold of normal QOL requires further study. Whether QOL in the EA group will remain improved after long-term follow-up (5-year or longer) requires further research.

The clinical implications of this study showed that the EA procedure seems to confer clinical benefit in terms of postoperative QOL, especially in the form of improved meal intake, reduced gastroesophageal reflux, and improved body weight, however, overall survival rate and surgical results are the same using all three procedures. Our data suggest that, to avoid gastroesophageal reflux and improve QOL in patients with upper third gastric cancer after proximal gastrectomy, the EA procedure for reconstruction using a stapler is safe and feasible for esophagogastrostomy. However, better reconstruction methods are still required to decrease postoperative symptoms in the future.

Given equivalent results with regards to survival, the impact of anastomotic methods on quality of life (QOL) becomes even more important. QOL is the main outcome for judging the efficacy of treatment modalities when no overall survival differences are demonstrated.

There is still no consensus on how to choose a reconstruction method for proximal gastrectomy in patients with upper third gastric cancer. This study was designed to compare in detail different methods of esophagogastrostomy.

No previous studies have assessed different methods of esophagogastrostomy in terms of QOL. The aim of this study was to assess outcome in terms of QOL in patients after proximal gastrectomy, by comparing three methods of esophagogastrostomy, in order to find the optimal reconstruction method that offers the optimal postoperative QOL.

The clinical implications of this study showed that the anterior wall end-to-side anastomosis combined with pyloroplasty (EA) procedure seems to confer clinical benefit in terms of postoperative QOL, especially in the form of improved meal intake, reduced gastroesophageal reflux, and improved body weight.

The Spitzer QOL Index, which reflects the patient’s postoperative status of health perception, is a global health assessment with a valid questionnaire, which includes five items: activity, daily living, health, support of family and friends, and outlook.

The authors evaluated postoperative QOL in patients with upper third gastric cancer, who received proximal gastrectomy with additional esophagogastrostomy. The results suggest that to avoid gastroesophageal reflux and improve QOL for patients with upper third gastric cancer after proximal gastrectomy, the EA procedure of reconstruction using a stapler is safe and feasible for esophagogastrostomy.

| 1. | Beitz J, Gnecco C, Justice R. Quality-of-life end points in cancer clinical trials: the U.S. Food and Drug Administration perspective. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 1996;7-9. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Horváth OP, Kalmár K, Cseke L, Pótó L, Zámbó K. Nutritional and life-quality consequences of aboral pouch construction after total gastrectomy: a randomized, controlled study. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2001;27:558-563. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Velanovich V. The quality of quality of life studies in general surgical journals. J Am Coll Surg. 2001;193:288-296. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Ichikawa D, Ueshima Y, Shirono K, Kan K, Shioaki Y, Lee CJ, Hamashima T, Deguchi E, Ikeda E, Mutoh F. Esophagogastrostomy reconstruction after limited proximal gastrectomy. Hepatogastroenterology. 2001;48:1797-1801. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma - 2nd English Edition -. Gastric Cancer. 1998;1:10-24. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Harrison LE, Karpeh MS, Brennan MF. Total gastrectomy is not necessary for proximal gastric cancer. Surgery. 1998;123:127-130. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Kitamura K, Yamaguchi T, Nishida S, Yamamoto K, Ichikawa D, Okamoto K, Taniguchi H, Hagiwara A, Sawai K, Takahashi T. The operative indications for proximal gastrectomy in patients with gastric cancer in the upper third of the stomach. Surg Today. 1997;27:993-998. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | Malý T, Zonca P, Neoral C, Jurytko A. [Post-gastrectomy reconstruction]. Rozhl Chir. 2008;87:367-368, 370-375. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | Adachi Y, Suematsu T, Shiraishi N, Katsuta T, Morimoto A, Kitano S, Akazawa K. Quality of life after laparoscopy-assisted Billroth I gastrectomy. Ann Surg. 1999;229:49-54. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Skeel RT. Systemic assessment of the patients with cancer. Manual of cancer chemotherapy. 1st ed. Little Brown: Cleveland 1982; 13-21. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Spitzer WO, Dobson AJ, Hall J, Chesterman E, Levi J, Shepherd R, Battista RN, Catchlove BR. Measuring the quality of life of cancer patients: a concise QL-index for use by physicians. J Chronic Dis. 1981;34:585-597. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 12. | Kameyama J, Ishida H, Yasaku Y, Suzuki A, Kuzu H, Tsukamoto M. Proximal gastrectomy reconstructed by interposition of a jejunal pouch. Surgical technique. Eur J Surg. 1993;159:491-493. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 13. | Takeshita K, Saito N, Saeki I, Honda T, Tani M, Kando F, Endo M. Proximal gastrectomy and jejunal pouch interposition for the treatment of early cancer in the upper third of the stomach: surgical techniques and evaluation of postoperative function. Surgery. 1997;121:278-286. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 14. | Adachi Y, Inoue T, Hagino Y, Shiraishi N, Shimoda K, Kitano S. Surgical results of proximal gastrectomy for early-stage gastric cancer: jejunal interposition and gastric tube reconstruction. Gastric Cancer. 1999;2:40-45. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 15. | Adachi Y, Katsuta T, Aramaki M, Morimoto A, Shiraishi N, Kitano S. Proximal gastrectomy and gastric tube reconstruction for early cancer of the gastric cardia. Dig Surg. 1999;16:468-470. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 16. | Svedlund J, Sullivan M, Liedman B, Lundell L. Long term consequences of gastrectomy for patient's quality of life: the impact of reconstructive techniques. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:438-445. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 17. | Takase M, Sumiyama Y, Nagao J. Quantitative evaluation of reconstruction methods after gastrectomy using a new type of examination: digestion and absorption test with stable isotope 13C-labeled lipid compound. Gastric Cancer. 2003;6:134-141. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 18. | Ogoshi K, Okamoto Y, Nabeshima K, Morita M, Nakamura K, Iwata K, Soeda J, Kondoh Y, Makuuchi H. Focus on the conditions of resection and reconstruction in gastric cancer. What extent of resection and what kind of reconstruction provide the best outcomes for gastric cancer patients? Digestion. 2005;71:213-224. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 19. | Matsushiro T, Hariu T, Nagashima H, Yamamoto K, Imaoka Y, Yamagata R, Okuyama S, Mishina H. Valvuloplasty plus fundoplasty to prevent esophageal regurgitation in esophagogastrostomy after proximal gastrectomy. Am J Surg. 1986;152:314-319. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 20. | Merendino KA, Dillard DH. The concept of sphincter substitution by an interposed jejunal segment for anatomic and physiologic abnormalities at the esophagogastric junction; with special reference to reflux esophagitis, cardiospasm and esophageal varices. Ann Surg. 1955;142:486-506. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 21. | Hoshikawa T, Denno R, Ura H, Yamaguchi K, Hirata K. Proximal gastrectomy and jejunal pouch interposition: evaluation of postoperative symptoms and gastrointestinal hormone secretion. Oncol Rep. 2001;8:1293-1299. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 22. | Buhl K, Schlag P, Herfarth C. Quality of life and functional results following different types of resection for gastric carcinoma. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1990;16:404-409. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 23. | Nomura E, Shinohara H, Mabuchi H, Sang-Woong L, Sonoda T, Tanigawa N. Postoperative evaluation of the jejunal pouch reconstruction following proximal and distal gastrectomy for cancer. Hepatogastroenterology. 2004;51:1561-1566. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 24. | Paimela H, Ketola S, Iivonen M, Tomminen T, Könönen E, Oksala N, Mustonen H. Long-term results after surgery for gastric cancer with or without jejunal reservoir: results of surgery for gastric cancer in Kanta-Häme central hospital in two consecutive periods without or with jejunal pouch reconstruction in 1985-1998. Int J Gastrointest Cancer. 2005;36:147-153. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 25. | Iwata T, Kurita N, Ikemoto T, Nishioka M, Andoh T, Shimada M. Evaluation of reconstruction after proximal gastrectomy: prospective comparative study of jejunal interposition and jejunal pouch interposition. Hepatogastroenterology. 2006;53:301-303. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 26. | Nishimura M, Honda I, Watanabe S, Nagata M, Souda H, Miyazaki M. Recurrence in jejunal pouch after proximal gastrectomy for early upper gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2003;6:197-201. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 27. | Katsube T, Konno S, Hamaguchi K, Shimakawa T, Naritaka Y, Ogawa K. Complications after proximal gastrectomy with jejunal pouch interposition: report of a case. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2005;31:1036-1038. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 28. | Tokunaga M, Ohyama S, Hiki N, Hoshino E, Nunobe S, Fukunaga T, Seto Y, Yamaguchi T. Endoscopic evaluation of reflux esophagitis after proximal gastrectomy: comparison between esophagogastric anastomosis and jejunal interposition. World J Surg. 2008;32:1473-1477. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 29. | Khan OA, Manners J, Rengarajan A, Dunning J. Does pyloroplasty following esophagectomy improve early clinical outcomes? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2007;6:247-250. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 30. | Masqusi S, Velanovich V. Pyloroplasty with fundoplication in the treatment of combined gastroesophageal reflux disease and bloating. World J Surg. 2007;31:332-336. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 31. | Nakane Y, Michiura T, Inoue K, Sato M, Nakai K, Ioka M, Yamamichi K. Role of pyloroplasty after proximal gastrectomy for cancer. Hepatogastroenterology. 2004;51:1867-1871. [Cited in This Article: ] |