Published online Mar 28, 2008. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.1946

Revised: December 7, 2007

Published online: March 28, 2008

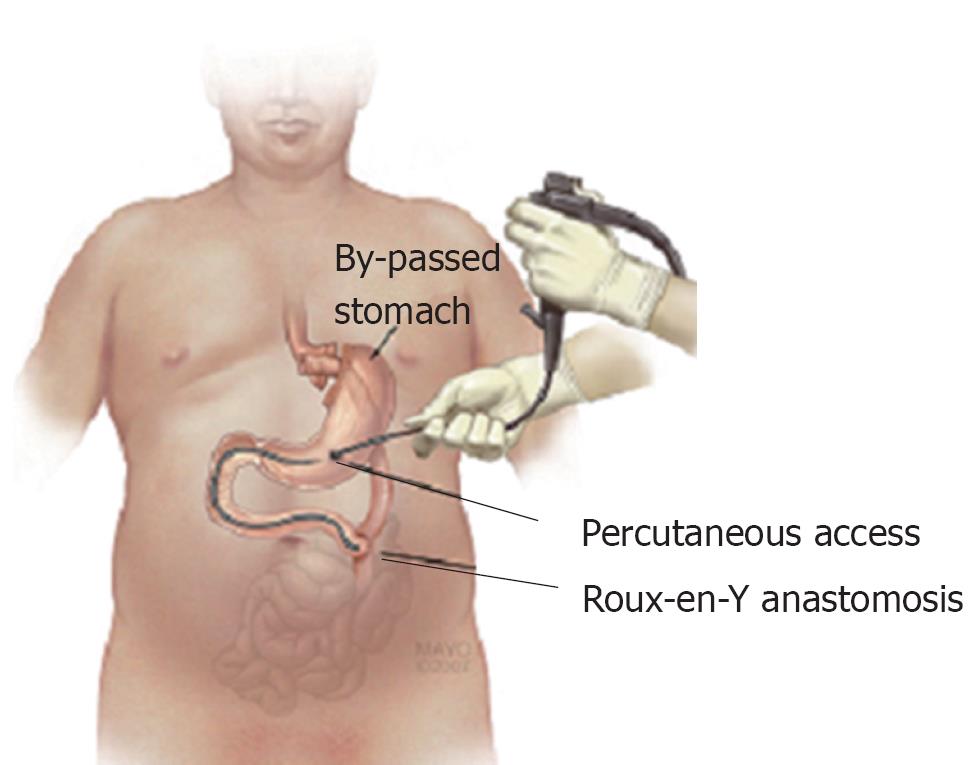

Accessing the bypassed portion of the stomach via conventional endoscopy is difficult following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. However, endoscopic examination of the stomach and small bowel is possible through percutaneous access into the bypassed stomach (BS) with a combined radiologic and endoscopic technique. We present a case of obscure overt gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding where the source of bleeding was thought to be from the BS. After conventional endoscopic methods failed to examine the BS, percutaneous endoscopy (PE) was used as an alternative to surgical exploration.

- Citation: Gill KR, McKinney JM, Stark ME, Bouras EP. Investigation of the excluded stomach after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: The role of percutaneous endoscopy. World J Gastroenterol 2008; 14(12): 1946-1948

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v14/i12/1946.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.14.1946

Bleeding from the bypassed stomach (BS) in patients following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery (GBS) is uncommon and can be a challenging diagnostic and therapeutic task. When the BS is not reachable by conventional approaches or more novel methods (e.g, double balloon endoscopy), surgical exploration may provide the only access to the BS and small bowel. Percutaneous endoscopy (PE) provides an opportunity to examine the BS and bowel and could be considered a practical alternative to surgical exploration.

A 66-year-old man status post Roux-en-Y GBS for morbid obesity 6 years prior presented to an outside institution with melena and hemodynamic instability. His hemoglobin (Hgb) was 10 gm, a drop from baseline Hgb of 15 gm. The patient was taking aspirin 81 mg daily. Upper endoscopy revealed expected post-surgical changes, and colonoscopy showed diverticulosis with no bleeding. A tagged RBC scan revealed a focus of activity in the right upper quadrant. Aspirin medication was stopped and the patient was discharged following cessation of clinical bleeding and a stable Hgb. He was readmitted 5 d later with recurrent melena and an Hgb of 8.5 gm. Repeat bleeding scan was negative, but CE revealed bleeding at 4 h into the recording (suspected jejunum). The Roux-en-Y anastomosis was not identified.

The patient was transferred to our institution for DBE, but the Roux-en-Y anastomosis was not reached, and no proximal source of bleeding was identified. Based on the suspicion that bleeding was coming from the BS, diagnostic and therapeutic alternatives including open or laparoscopic surgical exploration with gastroscopy and possible gastrectomy were considered. Surgery was considered high risk because of patient’s obesity and other comorbid conditions. As an alternative to surgical exploration, we endeavored to examine the BS using a combined approach with interventional radiology and endoscopy.

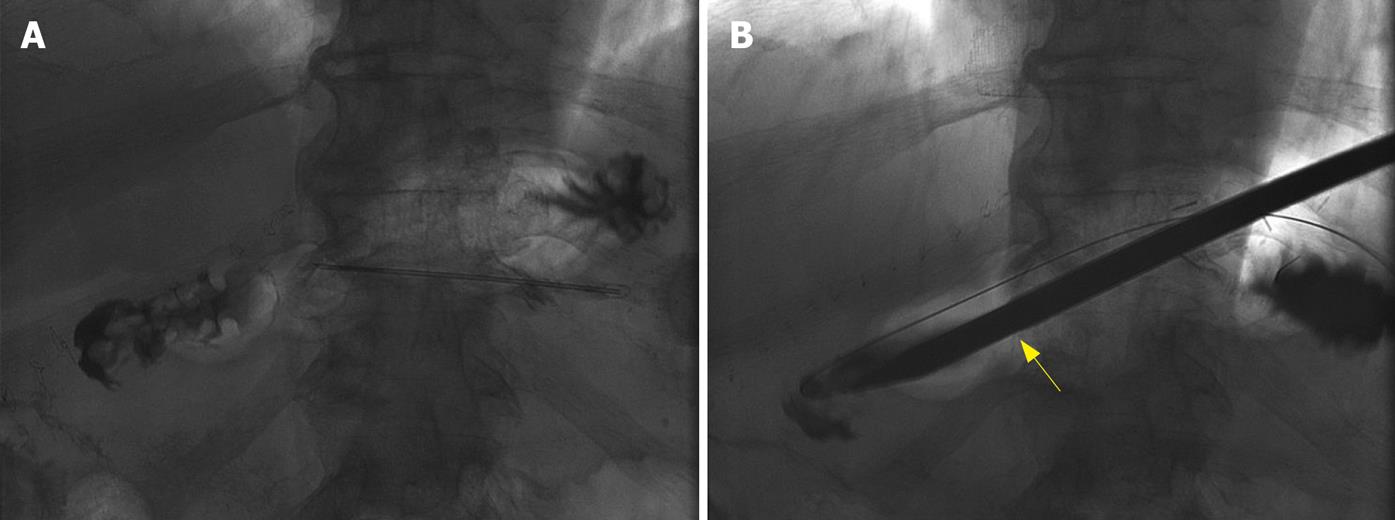

After a thorough discussion of potential risks and benefits, informed consent was obtained. One milligram of intravenous glucagon was administered to prevent gastric peristalsis. Once the BS was identified with real-time transabdominal ultrasonography, a 19-gauge needle was passed into the collapsed lumen of the BS under sterile conditions. The stomach was then inflated with air while progress was monitored with fluoroscopy (Figure 1A).

Three gastric anchors were inserted into the central portion of the BS, pulling the gastric wall to the abdominal wall. A trochar was inserted, the tract was dilated, and a 30 French sheath was placed under fluoroscopic guidance (Figure 1B).

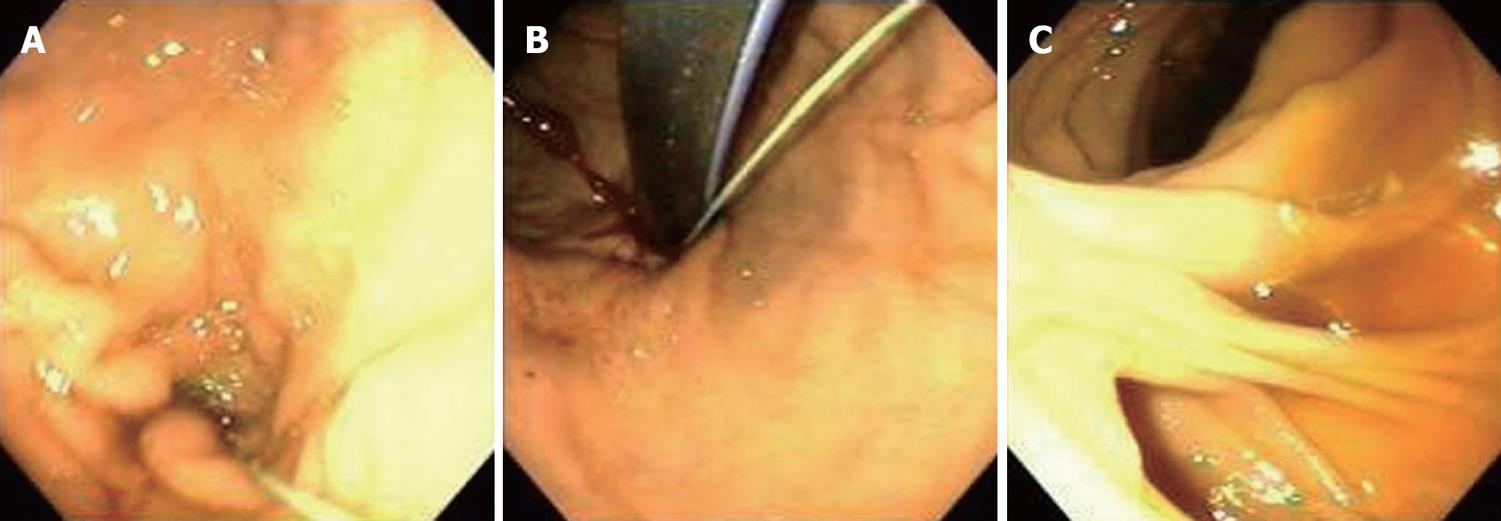

Through the sheath, a standard Olympus endoscope was introduced into the BS and examination was performed in antegrade and retrograde fashion (Figure 2A and B). The endoscope was advanced through the stomach and small bowel to the Roux-en-Y (Figure 3) anastomosis, where the two additional limbs of small bowel were examined for a distance of approximately 10 cm (Figure 2C). No source of bleeding was identified. After completion of the endoscopy, a 22 French gastrostomy tube (PEG) was placed in the BS for future access in the event of rebleeding. The patient experienced no clinical bleeding and had a stable Hgb, so he was discharged with the PEG (later changed to a button PEG) in place. As no bleeding occurred after 3 mo, the gastrostomy tube was removed.

The prevalence of obesity in the United States is reaching epidemic proportions. An estimated 30% of individuals met the criteria for obesity in 1999-2002[12]. The increasing numbers of obese individuals have led to intensified interest in GBS. The estimated numbers of bariatric surgical procedures in United States have increased from 13 365 in 1998 to 72 177 in 2002[3]. GBS is an effective and safe procedure; however, gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding after GBS can occur with an incidence of 0.8% to 4.4%[45].

Bleeding after GBS has been classified as early (< 48 h) and late (> 48 h)[6]. Late bleeding usually indicates luminal bleeding, whereas early bleeding may apply to bleeding intraluminally or into the abdominal cavity. The most common etiology of bleeding from BS is peptic ulcer disease (PUD), but the true incidence of bleeding from the BS is not known. One series reported only 8 of 3000 (0.26%) patients experienced GI bleeding from PUD involving the BS[7].

Endoscopic examination of the BS is a challenge in this patient population as it is difficult to reach the BS with conventional endoscopy. Flickinger and colleagues described the use of a pediatric colonoscope in 1985. In that series of 78 procedures, 68% of the attempts to pass through the jejunostomy for retrograde evaluation of duodenum and BS were successful[7]. Later, Sinar et al evaluated the BS by retrograde endoscopy and reported a successful procedure in 65% (33/51) of their patients[8].

Percutaneous examination of the BS with contrast was first described by McNeely et al in 1987[9]. In a series of 14 patients (11 nausea/pain, 3 GI bleeding), the radiocontrast examination was successful in 13/14 patients. However, the specificity of the findings was low as only 20% (1/5) of the patients had confirmation of the suspected diagnosis. Endoscopic examination through percutaneous access with a bronchoscope was first reported in 1998[10]. Since then, only a few case reports have been published utilizing PE to evaluate suspected pathology in the BS[1112].

New noninvasive techniques like virtual endoscopy have been evaluated for examination of BS in a small series[13]. However, more studies are needed to define the utility of the technique. Recently a case series utilizing DBE reported successful examination of the BS in 83.3% (5/6) of the cases[14]. The BDE technique enjoys several advantages over the more invasive percutaneous approach, but examination with DBE may be limited by difficult access, as with our patient, necessitating alternative approaches.

In this case no identifiable source of bleeding was found and hence the gastrostomy tube was left in place for future access. This is an advantage of the percutaneous approach as the stomach can be flushed and assessed in the event of bleeding. The access also allows a portal for endoscopy (requiring standard equipment and no special training). Fortunately, our patient had no further bleeding, so the gastrostomy tube was removed after 3 mo of observation.

In conclusion, this case highlights the value of PE to examine the BS after Roux-en-Y GBS. Advantages of this technique include direct access to the BS and the ability to leave an access point in the event of recurrent bleeding. Moreover, less endoscopic expertise is required compared to DBE, and the procedure is less invasive than surgery particularly in patients with multiple comorbidities.

| 1. | Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Johnson CL. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999-2000. JAMA. 2002;288:1723-1727. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Hedley AA, Ogden CL, Johnson CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, Flegal KM. Prevalence of overweight and obesity among US children, adolescents, and adults, 1999-2002. JAMA. 2004;291:2847-2850. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Santry HP, Gillen DL, Lauderdale DS. Trends in bariatric surgical procedures. JAMA. 2005;294:1909-1917. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Maggard MA, Shugarman LR, Suttorp M, Maglione M, Sugerman HJ, Livingston EH, Nguyen NT, Li Z, Mojica WA, Hilton L. Meta-analysis: surgical treatment of obesity. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:547-559. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Nguyen NT, Longoria M, Chalifoux S, Wilson SE. Gastrointestinal hemorrhage after laparoscopic gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2004;14:1308-1312. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Printen KJ, LeFavre J, Alden J. Bleeding from the bypassed stomach following gastric bypass. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1983;156:65-66. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Flickinger EG, Sinar DR, Pories WJ, Sloss RR, Park HK, Gibson JH. The bypassed stomach. Am J Surg. 1985;149:151-156. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | Sinar DR, Flickinger EG, Park HK, Sloss RR. Retrograde endoscopy of the bypassed stomach segment after gastric bypass surgery: unexpected lesions. South Med J. 1985;78:255-258. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | McNeely GF, Kinard RE, Macgregor AM, Kniffen JC. Percutaneous contrast examination of the stomach after gastric bypass. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1987;149:928-930. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Fobi MA, Chicola K, Lee H. Access to the bypassed stomach after gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 1998;8:289-295. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Shahriari A, Hinder RA, Stark ME, Williams HJ, Lange SM. Recurrent severe gastrointestinal bleeding complicating treatment of morbid obesity. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2000;31:19-22. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 12. | Sundbom M, Nyman R, Hedenstrom H, Gustavsson S. Investigation of the excluded stomach after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2001;11:25-27. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 13. | Silecchia G, Catalano C, Gentileschi P, Elmore U, Restuccia A, Gagner M, Basso N. Virtual gastroduodenoscopy: a new look at the bypassed stomach and duodenum after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for morbid obesity. Obes Surg. 2002;12:39-48. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 14. | Sakai P, Kuga R, Safatle-Ribeiro AV, Faintuch J, Gama-Rodrigues JJ, Ishida RK, Furuya CK Jr, Yamamoto H, Ishioka S. Is it feasible to reach the bypassed stomach after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for morbid obesity? The use of the double-balloon enteroscope. Endoscopy. 2005;37:566-569. [Cited in This Article: ] |