Published online Apr 28, 2006. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i16.2588

Revised: February 5, 2006

Accepted: February 10, 2006

Published online: April 28, 2006

AIM: To identify patients with a high-risk of having a synchronous cancer among gastric cancer patients.

METHODS: We retrospectively analyzed the prospective gastric cancer database at the National Cancer Center, Korea from December 2000 to December 2004. The clinicopathological characteristics of patients with synchronous cancers and those of patients without synchronous cancers were compared. Multivariate analysis was performed to identify the risk factors for the presence of a synchronous cancer in gastric cancer patients.

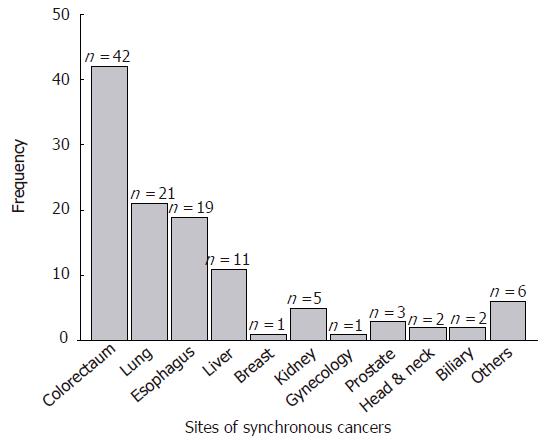

RESULTS: 111 of 3 291 gastric cancer patients (3.4%) registered in the database had a synchronous cancer. Among these 111 patients, 109 had a single synchronous cancer and 2 patients had two synchronous cancers. The most common form of synchronous cancer was colorectal cancer (42 patients, 37.2%) followed by lung cancer (21 patients, 18.6%). Multivariate analyses revealed that elderly patients with differentiated early gastric cancer have a higher probability of a synchronous cancer.

CONCLUSION: Synchronous cancers in gastric cancer patients are not infrequent. The physicians should try to find synchronous cancers in gastric cancer patients, especially in the elderly with a differentiated early gastric cancer.

- Citation: Lee JH, Bae JS, Ryu KW, Lee JS, Park SR, Kim CG, Kook MC, Choi IJ, Kim YW, Park JG, Bae JM. Gastric cancer patients at high-risk of having synchronous cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12(16): 2588-2592

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v12/i16/2588.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v12.i16.2588

Gastric cancer is the most common form of cancer in Korea[1]. The overall age-standardized incidence rates of gastric cancer in 2002 were 69.6 per 100 000 among males and 26.8 per 100 000 among females. Despite the improved prognosis of gastric cancer resulting from early diagnosis, radical operations, and the development of adjuvant therapy, gastric cancer remains the second most common cause of cancer death worldwide[2,3]. In 1995, early gastric cancer (EGC) accounted over 30% of patients who underwent gastric cancer surgery in Korea and this percentage continues to increase[4]. As the prognosis of patients with EGC is excellent and age at diagnosis for gastric cancer is increasing, there is a greater risk that patients will also have a second primary cancer[5,6].

Second primary cancer influences the prognosis of gastric cancer patients, and because primary or secondary prevention is the best way to cure cancer, some investigators have focused on the characteristics of second primary cancers in gastric cancer patients[7-10]. However, few studies have been performed in this regard, and most of these studies are limited to metachronous cancers or the treatment-related second primary malignancies of gastric cancer patients[11,12]. The detection of synchronous cancers gives us the opportunity to treat both cancers simultaneously using less invasive techniques and thus to beneficially influence the prognosis and quality of life of these patients.

The aim of this study was to find a means of identifying gastric cancer patients at risk of having a synchronous cancer.

We retrospectively analyzed the prospective gastric cancer database at the National Cancer Center (NCC), Korea from December 2000 to December 2004. A total of 3291 gastric cancer patients were registered (the registered patients were consecutive patients who had ever visited out patient clinic in the Center for Gastric Cancer with a diagnosis of gastric cancer or who were diagnosed as having gastric cancer at our center) during the study period. Gastric and synchronous cancers were all pathologically confirmed.

Synchronous cancers were defined as cancers detected in organs other than the stomach, which were diagnosed at the time of or within 6 mo of the first cancer diagnosis[13]. For each synchronous cancer we ruled out of the possibility that synchronous cancer represented metastasis of gastric cancer by histologic examination. Clinicopathological characteristics including age, sex, histological classification, a preoperative diagnosis of early or advanced gastric cancer, and multiplicity of gastric cancer were compared for patients with and without synchronous cancers. As for histological classifications, tubular carcinoma and papillary adenocarcinoma were classified as differentiated types, whereas poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma, mucinous adenocarcinoma, and signet ring cell carcinoma were classified as undifferentiated types[14]. The characteristics of synchronous cancers including operability and when they were diagnosed were separately analyzed.

All statistical analyses were performed using the statistical software ‘Statistical Package for Social Sciences’ (SPSS) version 10.0 for Windows (SPSS, Inc, Chicago, IL). Inter-group (for patients with and without synchronous cancer) comparisons of clinicopathological variables were made using the Student t-test for continuous variables and using the two-tailed Chi-square test for discrete variables.

Risk factors influencing synchronous cancers were determined by logistic regression analysis. Hazard ratio as determined by multivariate analysis, was defined as the ratio of the probability that an event (with synchronous cancer or not) would occur to the probability that it would not occur. The predicting powers of covariates were expressed by calculating hazard ratios with a 95% confidence interval. The accepted level of significance was P < 0.05.

Among the 3291 gastric cancer patients, 111 patients

(3.4 %) had a synchronous cancer other than in the stomach; 2 patients (2/111 patients, 1.7%) had three cancers and the others had a single synchronous cancer. The mean age of patients with a synchronous cancer was higher than that of patients without (64.6 ± 9.5 vs 59.4 ±12.5, t = -0.453, P < 0.001) and male patients were more common among those with synchronous cancers (χ2=9.81, P = 0.002). Differentiated type and early gastric cancer were more common among patients with synchronous cancers (χ2=73.97, P < 0.001, χ2=19.65, P < 0.001 respectively, Table 1).

| Synchronous | Synchronous cancer With n (%) | Characteristics cancer Without n (%) | P value |

| Age (yr, mean±SD) | 64.6 ± 9.5 | 59.4 ± 12.5 | < 0.001 |

| Sex | 0.002 | ||

| Male | 90 (81.1) | 2144 (67.4) | |

| Female | 21 (18.9) | 1036 (32.6) | |

| Multiplicity | 0.009 | ||

| Single | 106 (95.5) | 3146 (98.9) | |

| Multiple | 5 (4.5) | 34 (1.1) | |

| Preoperative Stage | < 0.001 | ||

| Early gastric cancer | 62 (55.4) | 1135 (35.7) | |

| Advanced gastric cancer | 50 (44.6) | 2045 (64.3) | |

| Differentiation | < 0.001 | ||

| Differentiated | 94 (84.7) | 1383 (43.4) | |

| Undifferentiated | 17 (15.3) | 1797 (56.6) |

The most common synchronous cancer was colorectal cancer (42 cases, 37.2%), followed by the lung (21 cases, 18.6%), esophagus (19 cases, 16.8%), and liver cancer (11cases, 9.7%) (Figure 1, Table 2). Gastric cancer was the most common form of cancer among colorectal cancer patients with a synchronous cancer. Of the 2 triple cancer patients, one patient had esophageal cancer and prostate cancer and the other patient had lung cancer and colorectal cancer. Forty-three patients (38.1%) were diagnosed with gastric cancer and synchronous cancer simultaneously and 45 patients (39.8%) were diagnosed with synchronous cancers before gastric cancer, and 25 cases (21.1%) were diagnosed after receiving a diagnosis of gastric cancer.

| Location | Time interval between the diagnoses of synchronous and gastric cancers | |||

| 6 mo ~(n=45) | Simultaneos(n=43) | ~ 6 mo(n=25) | Total(n=1131, %) | |

| Colorectal | 28 | 6 | 8 | 42 (37.2) |

| Lung | 3 | 11 | 7 | 21 (18.6) |

| Esophagus | 8 | 11 | 0 | 19 (16.8) |

| Liver | 2 | 8 | 1 | 11 (9.7) |

| Breast | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (0.9) |

| Kidney | 0 | 2 | 3 | 5 (4.4) |

| Gynecologic | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 (0.9) |

| Prostate | 1 | 0 | 2 | 3 (2.7) |

| Head and neck | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 (1.8) |

| GB, bile duct | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 (1.8) |

| Others | 2 | 1 | 3 | 6 (5.3) |

Of the 111 patients with synchronous gastric cancers, 73 (64.6%) underwent gastric cancer surgery. Despite having a potentially resectable gastric cancer, 38 patients (34.2%) were treated non-surgically because of advanced synchronous cancer (19 patients, 50.0%), an advanced gastric cancer (6 patients, 15.8%), or patient refusal (11 patients, 28.9%), and other causes (2 patients).

Logistic regression analysis identified age at gastric cancer diagnosis, differentiation, and early or advanced gastric cancer as independent risk factors of synchronous gastric cancer. The incidence of synchronous cancer in elderly patients (≥60 years) with differentiated early gastric cancer was 9.3% (43/418 patients), while that in other patients was 2.4% (68/2 830 patients). Moreover, the incidence of colon cancer in elderly patients (≥60 years) with differentiated early gastric cancer was 3.5% (15/418 patients, Table 3).

| Covariate | β | SE | RR (95% CI) | P value |

| Age, yr (< 62 vs≥ 62) | 0.471 | 0.223 | 1.601 (1.035-2.477) | 0.035 |

| Sex (Male vs Female) | -0.430 | 0.250 | 0.650 (0.398-1.061) | 0.085 |

| Histology (Diff. vs Undiff.) | - 1.691 | 0.276 | 0.184 (0.107-0.316) | < 0.001 |

| Multiplicity (Single vs Multiple) | 0.288 | 0.412 | 1.334 (0.595-2.994) | 0.484 |

| Stage (EGC vs AGC) | -0.431 | 0.202 | 0.650 (0.437-0.966) | 0.033 |

The main findings of this study are; 1) That synchronous cancer has an incidence of 3.4% (111/3 291 patients) in gastric cancer patients; 2) That the most common type of synchronous cancer in gastric cancer patients is colorectal cancer (42 patients, 37.2%), followed by lung cancer (21 patients, 18.6%); and 3) That age at diagnosis, a differentiated gastric cancer, and early gastric cancer are risk factors of synchronous cancer in gastric cancer patients. The incidence of synchronous cancer has been reported to vary from 0.7% to 3.5%[7-12]. Reasons for these wide ranges of incidence are attributed to different study populations and methods. The lowest incidence of synchronous cancers in gastric cancer patients reported was 0.7%, and this study was a population-based study, whereas, the other studies were institution-based, like the present study. The relatively high incidence of synchronous cancer in our study (3.4%), despite the inclusion of patients with EGC and AGC, may be due to time. Most studies were performed before 2000, whereas the patients included in this study were diagnosed as having gastric and synchronous cancer from 2001. Thus, radiologic diagnostic tools, such as, computed tomography (CT) and positron emission tomography (PET) were considerably developed and diagnostic accuracy improved over the intervening period[15,16]. Another possible explanation might be that this study was conducted as a retrospective analysis of a prospective database, and that our institution is a cancer center and as such diagnostic efforts are more focused on the detection of cancers.

In the present study, colorectal cancer was the most common cancer among gastric cancer patients with a synchronous cancer. On the contrary, gastric cancer was the most common form of cancer among colorectal cancer patients with a synchronous cancer. This association between colorectal cancer and gastric cancer may be incidental; however, there is some basis to support the existence of such a relation. It is well known that gastric cancer is the second most common extra-colonic malignancy associated with hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) syndrome[17]. Moreover, a defect in the mismatch repair system has been suggested to play a role in the development of multiple cancers, but mechanistic basis for the development of synchronous cancers is unclear[18]. Preoperative endoscopy is a routine procedure in the Center for Colorectal Cancer in NCC for the patients with a colorectal cancer.

Most patients with synchronous colorectal cancers in this study were diagnosed within one month prior to receiving a diagnosis of gastric cancer, or were diagnosed while gastric cancer diagnosis. Patients with colorectal cancer frequently have symptoms of obstruction or bleeding, whereas the symptoms of gastric cancer patients are rare and vague[19,20]. In addition, esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) in colorectal cancer patients is one of our institutional policies. Thus, it is frequently the cases that the stages of gastric cancer and associated colorectal cancer are early and advanced, respectively. The incidences of most cancers are higher in men than in women and tend to increase with age, and patients with synchronous cancer in this study were more commonly elderly males. These findings are consistent with those of previous studies and might be associated with recent trends in gastric cancer epidemiology in Korea and characteristics of gastric cancer[1,2,4]. The high incidence of synchronous cancers found among early gastric cancer patients in the present study might be associated with the increasing incidence of early gastric cancer in Korea, and the fact that patient diagnosed as having colorectal cancer undergo routine gastroscopy. However, the reason for the higher incidence of differentiated type in gastric cancer patients with synchronous cancer is unclear, and requires further investigation.

The incidence of synchronous cancer in those with multiple gastric cancers tended to be higher than for those with a single gastric cancer. Thus, genetic instability such as microsatellite instability might be involved in the development of synchronous cancer and multiple gastric cancers. However, the multiplicity of gastric cancer proved not to be a risk factor of synchronous cancer by multivariate analysis.

Regardless of the fact that they had potentially curable gastric cancer, 38 (35.4%) patients did not undergo an operation, and the presence of an advanced synchronous cancer was a principal reason. The major factor influencing treatment plans was cancer stage. Therefore, urgent efforts should be made to identify those at high-risk of having a synchronous cancer.

Multivariate analysis showed that age at gastric cancer diagnosis of, tumor differentiation, and preoperative stage are risk factors for the presence of synchronous cancer in gastric cancer patients. Elderly patients (≥60 years) with differentiated type of early gastric cancer had a synchronous cancer incidence of 9.3% and a synchronous colon cancer incidence of 3.5%. This result suggests that elderly patients with differentiated type of early gastric cancer should be assessed for the presence of a synchronous cancer. Most synchronous cancers, such as, colorectal, lung, esophageal, and liver cancers can be discovered during routine preoperative staging work up using EGD and radiologic examinations, such as, chest X-ray or abdomino-pelvic CT. However, the early detection of colorectal cancer, which proved to be the most common synchronous cancer type, requires colonoscopy.

Despite the fact that this study was conducted based on an analysis of a prospective database, not all patient information was recorded, because almost one third of the patients were not treated at our institution. Therefore, the preoperative stage was not always the same as the pathological stage. However, considering that the accuracy of preoperative staging for EGC or AGC is > 80%, we believe that our results would have been comparatively unchanged had we adopted pathological stage[21].

Colonoscopy is not routinely performed at our center in gastric cancer patients scheduled to undergo an operation or endoscopic mucosal resection. Because the indications for endoscopic mucosal resection are a differentiated cancer of < 2cm in diameter, those patients that undergo EMR present a group at high-risk of having a synchronous cancer. Moreover, it is likely that the incidence of synchronous colon cancer may have been higher if we had performed routine colonoscopy in these patients. We now plan to perform a routine colonoscopic examination on those determined by this study to be at high-risk.

In conclusion, synchronous cancers in gastric cancer patients are not infrequent. Considering the trend that the peak age of gastric cancer patients and the incidence of early gastric cancer are increasing, the present study cautions that physicians should try to find synchronous cancers in gastric cancer patients at risk, such as, in elderly patients with differentiated early gastric cancer.

S- Editor Pan BR L- Editor Zhang JZ E- Editor Bai SH

| 1. | Lee JH, Kim J, Cheong JH, Hyung WJ, Choi SH, Noh SH. Gastric cancer surgery in cirrhotic patients: result of gastrectomy with D2 lymph node dissection. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:4623-4627. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Hartgrink HH, van de Velde CJ, Putter H, Bonenkamp JJ, Klein Kranenbarg E, Songun I, Welvaart K, van Krieken JH, Meijer S, Plukker JT. Extended lymph node dissection for gastric cancer: who may benefit Final results of the randomized Dutch gastric cancer group trial. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2069-2077. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 647] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 633] [Article Influence: 31.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Yoo CH, Noh SH, Shin DW, Choi SH, Min JS. Recurrence following curative resection for gastric carcinoma. Br J Surg. 2000;87:236-242. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 523] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 531] [Article Influence: 22.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Yang HK; Information Committee of Korean Gastric Cancer Association. Nationwide survey of the database system on gastric cancer patients. J Korean Gastric Cancer Assoc. 2004;4:15-26. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Moertel CG. Multiple primary malignant neoplasms: historical perspectives. Cancer. 1977;40:1786-1792. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Urano Y, Itoyama S, Fukushima T, Kitamura S, Mori H, Baba K, Aizawa S. Multiple primary cancers in autopsy cases of Tokyo University Hospital (1883-1982) and in Japan Autopsy Annuals (1974-1982). Jpn J Clin Oncol. 1985;15 Suppl 1:271-279. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Ikeda Y, Saku M, Kawanaka H, Nonaka M, Yoshida K. Features of second primary cancer in patients with gastric cancer. Oncology. 2003;65:113-117. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 67] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Yoshino K, Asanuma F, Hanatani Y, Otani Y, Kumai K, Ishibiki K. Multiple primary cancers in the stomach and another organ: frequency and the effects on prognosis. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 1985;15 Suppl 1:183-190. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | Prior P, Waterhouse JA. Multiple primary cancers of breast and cervix uteri: an epidemiological approach to analysis. Br J Cancer. 1981;43:623-631. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 42] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Vrabec DP. Multiple primary malignancies of the upper aerodigestive system. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1979;88:846-854. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Lundegårdh G, Hansson LE, Nyrén O, Adami HO, Krusemo UB. The risk of gastrointestinal and other primary malignant diseases following gastric cancer. Acta Oncol. 1991;30:1-6. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 24] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kato I, Kito T, Nakazato H, Tominaga S. Second malignancy in stomach cancer patients and its possible risk factors. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 1986;16:373-381. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 13. | Adachi Y, Yasuda K, Inomata M, Sato K, Shiraishi N, Kitano S. Pathology and prognosis of gastric carcinoma: well versus poorly differentiated type. Cancer. 2000;89:1418-1424. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kim HS, Han HY, Choi JA, Park CM, Cha IH, Chung KB, Mok YJ. Preoperative evaluation of gastric cancer: value of spiral CT during gastric arteriography (CTGA). Abdom Imaging. 2001;26:123-130. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 38] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Chen J, Cheong JH, Yun MJ, Kim J, Lim JS, Hyung WJ, Noh SH. Improvement in preoperative staging of gastric adenocarcinoma with positron emission tomography. Cancer. 2005;103:2383-2390. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 168] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Herring JA, Shivangi U, Hall CC, Mihas AA, Lynch C, Vijay-Munshi N, Hall TJ. Multiple synchronous primaries of the gastrointestinal tract: a molecular case report. Cancer Lett. 1996;110:1-9. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 4] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Miyoshi E, Haruma K, Hiyama T, Tanaka S, Yoshihara M, Shimamoto F, Chayama K. Microsatellite instability is a genetic marker for the development of multiple gastric cancers. Int J Cancer. 2001;95:350-353. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Schoenfeld P, Cash B, Flood A, Dobhan R, Eastone J, Coyle W, Kikendall JW, Kim HM, Weiss DG, Emory T. Colonoscopic screening of average-risk women for colorectal neoplasia. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2061-2068. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 341] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 375] [Article Influence: 19.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Fuchs CS, Mayer RJ. Gastric carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:32-41. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 489] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 518] [Article Influence: 17.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Habermann CR, Weiss F, Riecken R, Honarpisheh H, Bohnacker S, Staedtler C, Dieckmann C, Schoder V, Adam G. Preoperative staging of gastric adenocarcinoma: comparison of helical CT and endoscopic US. Radiology. 2004;230:465-471. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 190] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 204] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Soetikno R, Kaltenbach T, Yeh R, Gotoda T. Endoscopic mucosal resection for early cancers of the upper gastrointestinal tract. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:4490-4498. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 408] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 443] [Article Influence: 23.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |