Published online Apr 14, 2006. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i14.2201

Revised: October 1, 2005

Accepted: October 26, 2005

Published online: April 14, 2006

AIM: To report our experience with the use of granulocytapheresis (GCAP) in 14 patients with active steroid-refractory inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in order to evaluate its efficacy in achieving remission and maintaining a long lasting symptom-free period.

METHODS: The activity of the disease was evaluated by clinical activity index (CAI) and endoscopic index (EI) in ulcerative colitis (UC), while by Crohn’s disease activity index (CDAI) in Crohn's disease (CD). The patients were treated using the AdacolumnTM system, an adsorption column which selectively binds to granulocytes and monocytes. One session/week of GCAP was performed for 5 wk. Steroids were stopped during apheresis.

RESULTS: All the patients completed the five-week course showing no complications. At the end of the last session, 93% of patients showed a clinical remission of the disease that persisted for 6 mo. Nine months after the end of the treatment, 60% of the cases maintained remission, while 23% of the patients were still in clinical remission after 12 mo.

CONCLUSION: Even if the number of our patients with steroid-refractory IBDs was not big, we can assert that GCAP is well tolerated and effective, especially in the first six months after the treatment, in a significant percentage of cases. The rate of sustained response drops slightly after 6 mo and significantly after 12 mo, however the absence of severe side effects can be a stimulus for further evaluating new schedules of treatment.

- Citation: Giampaolo B, Giuseppe P, Michele B, Alessandro M, Fabrizio S, Alfonso C. Treatment of active steroid-refractory inflammatory bowel diseases with granulocytapheresis: Our experience with a prospective study. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12(14): 2201-2204

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v12/i14/2201.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v12.i14.2201

The term “inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)” usually means two similar but distinct chronic diseases of the gut: ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD) characterised by episodes of remission and exacerbation with systemic complications[1-4].

During the last 20 years the treatment of IBD has been greatly improved although it is still empirical due to its unknown aetiology[5-8]. It seems that both ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease are multifactorial in origin. However, regardless of the cause, the final pathway of tissue damage in IBD is mediated by the cellular immune response through white blood cells in the intestinal mucosa. Corticosteroids are a mainstay of acute therapy for moderate to severe ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease. However, up to 40% of patients do not respond to the high-dose steroid therapy. So, new therapeutic approaches are needed to improve the clinical outcome of active steroid-refractory IBD.

Classic immunosuppressant drugs like azathioprine or mercaptopurine need some weeks to exert their full activity, so they are useless during the acute phases of the disease. Moreover, newer immunosuppressants like cyclosporine A have shown only a temporary benefit and often serious side effects.

In recent years some trials have suggested that leukocytapheresis can be a useful and safe way to induce clinical remission in patients with IBD[9-11,15]. Subsequent trials have proved that granulocytapheresis (GCAP), a technique that sequestrates much selectively granulocyte and monocyte subpopulations, is equally effective in patients with active IBD[16,17].

Even if with a limited casuistry, we aimed at bulking the published data by referring our experience with GCAP. We analyzed the clinical, endoscopic and laboratory parameters of patients with active, steroid-refractory IBDs, before and after the completion of GCAP during a follow-up period of 12 mo. This work was to get more information about the real effectiveness of GCAP in achieving remission and possibly in maintaining it.

All the patients with UC or CD treated with GCAP in our department because of steroid-resistant IBD were followed up by monitoring clinical, laboratory and endoscopic parameters for UC.

Before admitted for GCAP, all patients signed an informed consent and underwent routine laboratory tests and basal ECG. Moreover, they were visited by a cardiologist in order to exclude serious cardiovascular diseases.

All patients received a 5-session (1 session/wk) treatment with GCAP. This was an extracorporeal procedure in which 1.8 L of blood was filtered through an AdacolumnTM (JIMRO, Takasaki, Japan). AdacolumnTM is a 335 mL capacity column filled with 35 000 cellulose diacetate beads (2 mm in diameter) that bind to granulocytes and monocytes via the CR3 receptors present on these cells. Each apheresis procedure required the addition of 1500 UI of sodium heparin as an anticoagulant. Blood was obtained by antecubital vein puncture. Methylprednisolone daily dose was progressively reduced until discontinuation in a 6-wk period (one week after the last apheresis procedure). Concomitant treatment with aminosalicylates was maintained during the treatment and follow-up at the same dosage.

In ulcerative colitis patients, the activity of the disease was evaluated by clinical activity index (CAI): Clinical remission was defined if less than 6 and endoscopic index (EI): endoscopic remission was defined if less than 4. In the subjects with Crohn’s disease, the activity was measured by Crohn's disease activity index (CDAI): clinical remission was defined if less than 150.

After the end of the five-week course of granulocytapheresis and every 3 mo, each patient was visited for a clinical and endoscopic assessment, paying particular attention to the activity indices. The subjects who achieved clinical remission were followed up for 12 mo by the last session of GCAP.

Relapse was defined as an increase of clinical and endoscopic scores (CAI, EI, CDAI) more than 6, 4 or 150 respectively. Patients who were on 5-aminosalicylic acid continued this medication but no additional treatment.

Hemograms, biochemistry and coagulation were recorded during the apheresis treatment.

Data were expressed as mean ± SD if required. Student’s t test for paired variables was performed. Statisticcal analyses were analysed with SPSS 11.5 (®SPSS inc. 2002).

We treated and followed up 14 patients (8 with ulcerative colitis and 6 with ileal Crohn’s disease).

Baseline characteristics of the 8 UC patients were mean age: 35.2±7.4 years; female/male ratio: 3:5; mean time of disease history: 7.8±3 years. All patients had an active pancolitis with a mean CAI of 10.0±3.4 at baseline and a mean endoscopic index (EI) score of 10.5±2.5 (Table 1). All the patients showed an active disease and were treated with 0.8-1 mg/kg pre d of i.v. or i.m. methylprednisolone and 2.4 g/d of oral mesalazine during the 8 wk period prior to GCAP initiation, without achieving response. None of the patients was under inmuno-supressor therapy at baseline but all of them were on mesalazine at 2.4 g/d.

| Female/Male | 3/5 |

| Age (yr) | 35.2±7.4 |

| Colonic involvement | All PanUC |

| Disease duration (yr) | 7.8±3.0 |

| Basal CAI | 10.0±3.4 |

| Basal EI | 10.5±2.5 |

Baseline characteristics of the 6 CD patients were mean age: 37.8±2.5 years; female/male ratio: 3:3; mean time of disease history: 7.1±3.2 years. All patients had an active ileal CD with a mean basal CDAI of 213.3±32.0 (Table 2).

| Female/Male | 3/3 |

| Age (yr) | 37.8±2.5 |

| Disease location | All ileal CD |

| Disease duration (yr) | 7.1±3.2 |

| Basal CDAI | 213.3±32.0 |

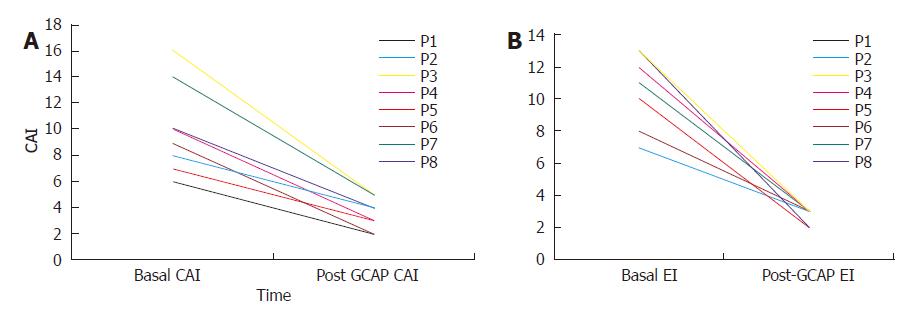

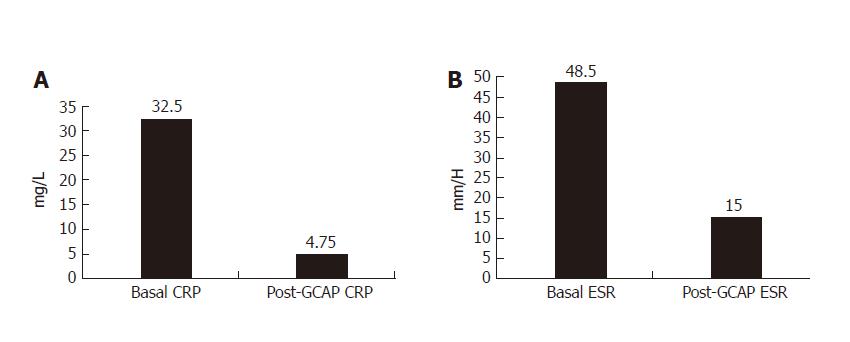

One week after GCAP treatment, all UC patients achieved remission (Figures 1A and 1B) and stopped methylprednisolone treatment. The mean CAI decreased from 10.0 ± 3.4 to 3.5 ± 1.2 (P < 0.001). Also EI decreased from 10.5±2.2 to 2.6 ± 0.5 (P < 0.001). The mean values of CRP and ESR decreased from 32.5 ± 11.2 to 4.5 ± 4.7 mg/L (P < 0.001) and 48.5 ± 8.6 to 15.0 ± 2.3 mm/h respectively (P < 0.001) (Figures 3A and 2B).

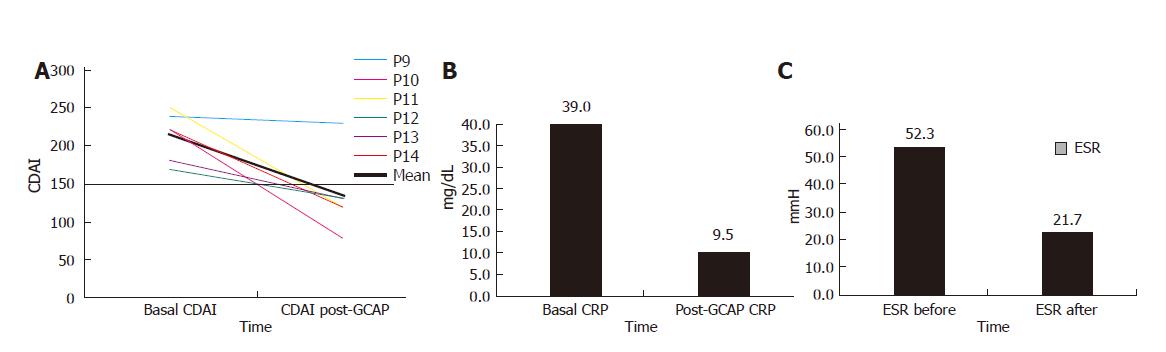

One week after GCAP treatment, 5 out of 6 patients achieved remission (Figure 3A) and stopped methylprednisolone treatment. The mean CDAI decreased from 213.3 ± 32.0 to 135 ± 50 (P < 0.015). The mean CRP values decreased from 39.0 ± 12.6 to 9.5 ± 9.1 mg/L (P < 0.01) and ESR values from 52.3 ± 9.8 to 21.7 ± 18.0 mm/h (P < 0.05) (Figures 3B and 3C).

All the patients completed GCAP without severe side effects. Only a transient mild headache was recorded in two patients during the procedure.

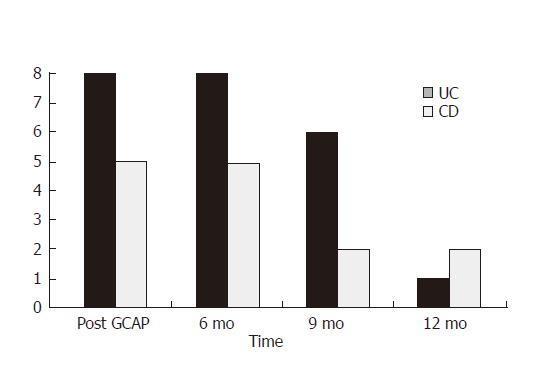

All the patients were followed up for 12 mo after GCAP treatment and no additional treatment was added. Clinical remission persisted for 6 mo in all the patients and was achieved early after apheresis (93%). At the 9th mo of follow-up, 6 of 8 UC patients and 2 of 5 CD patients were still in clinical remission. At the 12th mo of follow-up, only 1 of 8 UC patients and 2 of 5 CD patients were in remission (Figure 4).

Currently, the use of steroid drugs is a common strategy for the treatment of acute inflammatory bowel disease. However, large doses of steroids are often necessary to control active diseases and some patients do not respond to this conventional treatment. Colectomy rate varies from 10% to 40% in these patients[12]. The treatment with cyclosporin in these patients can avoid acute colectomy in 57% of cases, but after a 6-mo follow-up period 73% of patients undergo surgery[13]. Azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine has been reported to be beneficial for steroid resistant cases, but their use requires several weeks to get full effects[14].

Recent data from literature have pointed out that granulocytapheresis, which acts on specific subpopulations of leukocytes involved in the inflammatory process, can represent a useful and probably much safe treatment for patients with ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease[16,17].

In fact it is well known that inflammatory bowel disease is associated with elevated circulating and tissue levels of leukocytes. Granulocytes are the first cells mobilizing to inflammation sites and interact with lymphocytes to orchestrate the inflammatory response. For these reasons the removal of granulocytes may be a logical therapeutic manoeuvre. Moreover, the good results obtained so far by granulocytapheresis have been attributed not only to the removal of granulocytes and monocytes, but also to its immunomodulatory effect[10,11,15,16].

The goal of this study was to assess the safety and efficacy of GCAP in patients with active inflammatory bowel disease that was refractory to conventional drug therapy. In our small casuistry, the procedure was well tolerated and 93% of cases showed remission at the end of a five-week course of GCAP. No serious side effects were recorded and clinical/endoscopic remission lasted for six months in all the patients, achieved at the end of the therapeutic course (“responders”). Nine months after GCAP treatment, about 60% of responders were still in remission, without any significant difference between UC and CD patients. The remission rate dropped dramatically at the 12th mo, with slightly better outcome in CD patients.

In conclusion, this new approach to active steroid-refractory IBD seems an important innovation and a useful therapy after the failure of conventional treatments. GCAP is able to achieve clinical remission in a large proportion of “difficult” IBD patients. This new technique is virtually free of severe side effects and could be repeated more times if necessary.

We hope that our data could represent a stimulus for further trials aimed to evaluate the real usefulness of apheresis in IBD, to clarify the optimal length of treatment and to know which patients could get most benefit from it.

S- Editor Wang J L- Editor Wang XL E- Editor Liu WF

| 1. | SLOAN WP, BARGEN JA, GAGE RP. Life histories of patients with chronic ulcerative colitis: a review of 2,000 cases. Gastroenterology. 1950;16:25-38. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Mekhjian HS, Switz DM, Melnyk CS, Rankin GB, Brooks RK. Clinical features and natural history of Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 1979;77:898-906. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Farmer RG, Whelan G, Fazio VW. Long-term follow-up of patients with Crohn's disease. Relationship between the clinical pattern and prognosis. Gastroenterology. 1985;88:1818-1825. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Bresci G, Parisi G, Gambardella L, Banti S, Bertoni M, Rindi G, Capria A. Evaluation of clinical patterns in ulcerative colitis: a long-term follow-up. Int J Clin Pharmacol Res. 1997;17:17-22. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Bresci G, Parisi G, Bertoni M, Capria A. Long-term maintenance treatment in ulcerative colitis: a 10-year follow-up. Dig Liver Dis. 2002;34:419-423. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 21] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Summers RW, Switz DM, Sessions JT, Becktel JM, Best WR, Kern F, Singleton JW. National Cooperative Crohn's Disease Study: results of drug treatment. Gastroenterology. 1979;77:847-869. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Riis P, Anthonisen P, Wulff HR, Folkenborg O, Bonnevie O, Binder V. The prophylactic effect of salazosulphapyridine in ulcerative colitis during long-term treatment. A double-blind trial on patients asymptomatic for one year. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1973;8:71-74. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | Ardizzone S, Petrillo M, Imbesi V, Cerutti R, Bollani S, Bianchi Porro G. Is maintenance therapy always necessary for patients with ulcerative colitis in remission. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13:373-379. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 63] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Yamaji K, Fukunaga K, Yamane S, Sueoka A, Nosé Y. Current therapeutic apheresis technologies for inflammatory bowel disease. Ther Apher. 1998;2:105-108. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 6] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kawamura A, Saitoh M, Yonekawa M, Horie T, Ohizumi H, Tamaki T, Kukita K, Meguro J. New technique of leukocytapheresis by the use of nonwoven polyester fiber filter for inflammatory bowel disease. Ther Apher. 1999;3:334-337. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 19] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kohgo Y, Ashida T, Maemoto A, Ayabe T. Leukocytapheresis for treatment of IBD. J Gastroenterol. 2003;38 Suppl 15:51-54. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 12. | Kjeldsen J. Treatment of ulcerative colitis with high doses of oral prednisolone. The rate of remission, the need for surgery, and the effect of prolonging the treatment. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1993;28:821-826. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 23] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kozarek R, Bedard C, Patterson D, Justus P, Sandford R, Greene M, Gelfand M, Bredfeldt J, Brentnall T, Putnam W. Cyclosporin use in the precolectomy chronic ulcerative colitis patient: a community experience and its relationship to prospective and controlled clinical trials. Pacific Northwest Gastroenterology Society. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:2093-2096. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 14. | Su C, Lichtenstein GR. Treatment of inflammatory bowel disease with azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2004;33:209-34, viii. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 48] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Sawada K, Muto T, Shimoyama T, Satomi M, Sawada T, Nagawa H, Hiwatashi N, Asakura H, Hibi T. Multicenter randomized controlled trial for the treatment of ulcerative colitis with a leukocytapheresis column. Curr Pharm Des. 2003;9:307-321. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 146] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Saniabadi AR, Hanai H, Takeuchi K, Umemura K, Nakashima M, Adachi T, Shima C, Bjarnason I, Lofberg R. Adacolumn, an adsorptive carrier based granulocyte and monocyte apheresis device for the treatment of inflammatory and refractory diseases associated with leukocytes. Ther Apher Dial. 2003;7:48-59. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 198] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 202] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Suzuki Y, Yoshimura N, Saniabadi AR, Saito Y. Selective granulocyte and monocyte adsorptive apheresis as a first-line treatment for steroid naïve patients with active ulcerative colitis: a prospective uncontrolled study. Dig Dis Sci. 2004;49:565-571. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 115] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |