Published online Nov 14, 2005. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i42.6587

Revised: May 9, 2005

Accepted: May 12, 2005

Published online: November 14, 2005

AIM: To study the clinical significance of minimal ascites, which was only defined by the CT and whose nature was not determined preoperatively, in the relationship with the peritoneal carcinomatosis.

METHODS: The medical records and the dynamic CT films of 118 patients with gastric cancer were reviewed. Factors associated with peritoneal carcinomatosis were analyzed in 40 patients who had CT-defined ascites of which the nature was surgically confirmed.

RESULTS: Only 12.5-25% of the CT-defined minimal ascites, whose volume was estimated to be less than 50 mL, were associated with peritoneal carcinomatosis. When the estimated CT-defined ascitic volume was 50 mL or more, peritoneal carcinomatosis was identified in 75–100%. When CT-defined lymph node enlargements were not found beyond the regional gastric area, perigastric invasions were not suspected, and the size of tumor was less than 3 cm, peritoneal carcinomatosis seemed significantly less accompanied at the univariate analysis. However, except for the minimal volume of CT-defined ascites in comparison with the mild or more, other factors were not confirmed multivariately.

CONCLUSION: In the patients with gastric cancer, CT-defined minimal ascites alone is rarely associated with peritoneal carcinomatosis, if it does not accompany other signs suggestive of malignant seeding. Therefore, consideration of active curative resection should not be hesitated, if CT-defined minimal ascites is the only delusive sign.

- Citation: Chang DK, Kim JW, Kim BK, Lee KL, Song CS, Han JK, Song IS. Clinical significance of CT-defined minimal ascites in patients with gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2005; 11(42): 6587-6592

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v11/i42/6587.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v11.i42.6587

Gastric cancer, quite uncommon in the developed countries, is still the second leading cause of cancer death in the world[1]. Surgical resection is the only effective therapy to secure curability of this fatal disease. Therefore, overestimation of the stage to render surgery being given up is critically hazardous, as it could deprive a patient of a chance for cure.

The two most frequent conditions in which gastric cancer is regarded incurable are when distant metastasis and malignant peritoneal seeding are demonstrated[2]. Dynamic CT is an excellent modality in clinical staging for gastric cancer and reliably detects metastasis to distant organs such as liver or lung[3,4]. However, the accuracy of dynamic CT in assessing malignant peritoneal involvement is somewhat questionable[4]. The presence of ascites, intestinal wall thickening, contrast-enhanced density in peritoneal adipose tissues, or implanted peritoneal, mesenteric or omental nodules are commonly stated CT findings suggestive of peritoneal carcinomatosis[5,6]. Among these, ascites is assumed to be the most frequently occurring clue for malignant seeding[5].

The nature of ascites is easily disclosed by aspiration cytology as long as the quantity of intra-abdominal fluid enables paracentesis[7,8]. Even small amount of ascites could be recovered for analysis by ultrasonography-guided needle aspiration[9,10]. However, dynamic CT has now become extremely sensitive and may occasionally detect subtle and equivocal amount of ascites in the pelvis, too little for preoperative aspiration-based examination. Without a cytological study or other strong evidences of peritoneal carcinomatosis, the significance of CT-defined minimal ascites might be ambiguous.

In clinical practice, some degree of hesitation is unavoidable in proceeding to surgery, when peritoneal seeding is equivocally suspected. The aim of this study is to make obvious whether the minimal ascites, which was only defined by CT and whose nature was not practically feasible to characterize preoperatively, is related to genuine peritoneal carcinomatosis. We intend to draw a reasonable perception about ‘minimal’ ascites in view of clinical significance.

Between January 2002 and December 2002, 118 consecutive patients were diagnosed for gastric cancer based on the histological examination of a gastroscopic biopsy and were also examined by dynamic CT at Boramae hospital. Their medical records and CT films were retrospectively reviewed. Out of these, 11 patients did not complete all necessary diagnostic and therapeutic procedures and were excluded from the study. One patient with massive ascites caused by decompensated hepatic cirrhosis was also excluded. Finally, a total of 106 patients remained for an initial analysis (BRM02) for overall frequency of ascites, peritoneal carcinomatosis, and distant metastasis.

The nature of ascites was often unexplored in the patients with metastatic diseases, because curative surgery was not indicated for them and thus characterization of ascites was practically unnecessary. Therefore, when analyzing the clinical implications of CT-defined ascites, we excluded 17 metastatic cases. In the remaining 89 cases (BRM02-NoMeta), the relationships between CT-defined ascites, surgery- or aspiration-recovered ascites, and peritoneal carcinomatosis were analyzed.

Thereafter, we tried to find factors predicting the absence of peritoneal carcinomatosis in the patients with CT-defined ascites, whose nature could not be evaluated preoperatively. To obtain sufficient number of cases for statistical analysis, we extended the study subjects to the cases of Boramae Hospital and of Seoul National University Hospital during the periods between March 1998 and December 2002. We reviewed 2 365 CT reports of the cases who had undergone open abdominal surgery, so whose ascitic natures were confirmed. In this screening step based on the reports, we collected 40 operated cases in which the patients had CT-defined ascites of undetermined nature at preoperative phase and had no definite evidence of distant metastasis or apparent peritoneal seeding (BRM-SNU group). Their medical records and CT films were reviewed in detail.

Dynamic CT studies were performed with Somatom plus-4 scanner (Siemens Medical System, Erlangen, Germany). The abdomen and pelvis were scanned with helical technique and the image was reconstructed at 1-cm-thick sections. Patients were asked not to drink or eat anything for 8 h before CT examination. A total of 500-1 000 mL of tap water was given by mouth, immediately before scanning. A total of 80-120 mL of iopromide contrast medium (Ultravist370®, Schering, Berlin, Germany) was administrated by Mark V dedicated CT injector (Medrad, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) at a flow rate of 3 mL/s, through 18-gauge angiographic catheter placed in the antecubital vein.

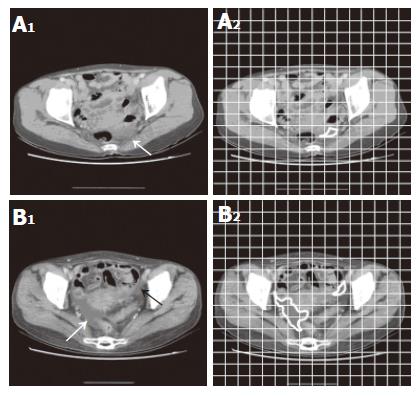

Ascites was defined at CT images by at least two experienced radiologists, when the reasonably low radiologic density of 10 or less Hounsfield number was found within the pelvic cavity outside intra-abdominal or pelvic organs. Volume of ascites was estimated by the ruler grids applied on CT images. For example, the area of ascites was measured about 3.5 cm2 in Figure 1A and 16 cm2 in Figure 1B and these respectively corresponded with the estimated volumes of 3.5 mL (3.5 cm2×1 cm) and 16 mL (16 cm2×1 cm), because the interval between the serial images obtained in the study was 1 cm. When fluid densities were detected in more than one image, the volumes at each image were added up.

‘Minimal’ ascites was defined, when the volume of ascites was estimated to be less than 50 mL, and ascites of 50-300 mL was defined as ‘mild’. Because we focused on the small amount of ascites which could not be easily evaluated by conventional measures at the preoperative stage, definition about moderate to severe ascites was not considered.

Obliteration of a fat plane between the stomach and adjacent organs or apparent infiltration shown in the CT images was regarded as tumor invasion. Lymph nodes were considered significantly enlarged, when the long diameter was more than 1 cm. The lymph nodes were classified as ‘regional’ when they were located along the lesser or the greater curvatures of stomach, or at the left gastric, common hepatic, celiac, or splenic arteries. Other intra-abdominal nodes beyond these regions, such as the hepatoduodenal, retropancreatic, mesenteric, or para-aortic area, were defined as distant lymph nodes.

Data were analyzed by SPSS (11.5th version) software. Chi-square test was used for categorical data analysis, and the univariate analysis and the multivariate logistic regression modeling were employed for assessing the predictive factors for the absence of peritoneal carcinomatosis in patients with CT-defined ascites.

One hundred and six patients committed to the initial analysis consisted of 70 men and 36 women with a mean age of 63.3 years. The stage of gastric cancer at diagnosis was stage I, 23.6%; stage II, 7.5%; stage III, 34.0%; and stage IV, 34.9%. Patients with early gastric cancers were 27.4%.

Of the BRM02 patients, 22 (20.7%) had ascites defined by CT images. Based on the estimated volume of ascites, 12 patients belonged to the category of minimal ascites and 10 patients had mild or more ascites (11.3% and 9.4% of all patients, respectively).

Twenty patients out of the 106 BRM02 group (18.9%) were found to have peritoneal carcinomatosis that was confirmed by preoperative aspiration cytology or laparotomy no matter, whether they had CT-defined ascites or not. Seventeen patients (16%) had metastatic diseases to distant organs. Among these, four patients (3.8%) were confirmed to have both distant metastasis and malignant peritoneal seeding (Table 1).

| Peritoneal carcinomatosis | ||||

| Distant metastasis | Negative | Positive | Unknown | Total |

| Negative | 73 (67/6/0)1 | 11 (6/2/3) | 0 | 84 (73/8/3) |

| Positive | 5 (4/1/0) | 4 (1/0/3) | 8 (5/3/0) | 17 (10/4/3) |

| Unknown | 0 | 5 (1/0/4) | 0 | 5 (1/0/4) |

| Total | 78 (71/7/0) | 20 (8/2/10) | 8 (5/3/0) | 106 (84/12/10) |

Out of the remaining 89 patients (BRM02-NoMeta) after excluding those with metastatic diseases, 8 had minimal ascites, and 7 had mild ascites. There were no patients having ascites greater than mild category in the metastasis-free group. The nature of ascites was explored by surgery, in all 8 cases with minimal ascites, and in 5 out of 7 cases with mild ascites. The remaining two patients’ ascites were proven malignant by aspiration cytology, and surgery was not performed.

Ascites defined by CT images were not always identified as peritoneal fluid on surgery. As for the CT-defined minimal ascites, ascitic fluid was recovered at the surgical field in only one (12.5%) of the cases. However, as CT-estimated ascitic volume was higher, surgical correlation improved. In the cases of ‘mild’ ascites which had more volume than ‘minimal’, the concordance rate between CT-defined ascites and surgery- or aspiration-recovered ascites was as high as 85.7% (6 out of 7). On the other hand, 5 (6.8%) out of 74 patients who had no CT-identified ascites preoperatively demonstrated ascites at the time of surgery (Table 2).

| Surgery- or aspiration-recovered ascites | ||||

| CT-defined ascites | Negative (%) | Positive (%) | Unknown (%) | Total (%) |

| No | 68 (91.9) | 5 (6.8) | 1 (1.4) | 74 (100) |

| Minimal | 7 (87.5) | 1 (12.5) | 0 (0.0) | 8 (100) |

| Mild | 0 (0.0) | 6 (85.7) | 1 (14.3) | 7 (100) |

| Total | 75 | 12 | 2 | 89 |

The relationship between CT-defined ascites and peritoneal carcinomatosis was analyzed (Table 3). Among the patients who did not show ascites at the CT images, seven (9.5%) had peritoneal carcinomatosis on surgery. Seven out of sixteen (43.8%) patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis did not demonstrate radiological signs of ascites at the preoperative CT. In the patients with CT-defined ‘minimal’ ascites, only 25% were concluded by surgery to have peritoneal carcinomatosis. This was contrast to the cases with CT-defined ‘mild’ ascites, in which all of the CT-defined ascites turned out to have occurred in the association with peritoneal carcinomatosis.

| Peritoneal carcinomatosis | |||

| CT-defined ascites | Negative (%) | Positive (%) | Total (%) |

| No | 67 (90.5) | 7 (9.5) | 74 (100) |

| Minimal | 6 (75.0) | 2 (25.0) | 8 (100) |

| Mild | 0 (0.0) | 7 (100) | 7 (100) |

| Total | 73 | 16 | 89 |

The presence of surgery- or aspiration-recovered ascites was not always accompanied with malignant peritoneal seeding, too. Four out of twelve patients (33.3%) with surgically or cytologically recovered ascites did not accompany peritoneal carcinomatosis, and 8% of ascites-free patients were actually positive for malignant peritoneal seeding (Table 4).

| Peritoneal carcinomatosis | |||

| Surgery- or aspiration-Recovered ascites | Negative (%) | Positive (%) | Total (%) |

| Negative | 69 (92.0) | 6 (8.0) | 75 (100) |

| Positive | 4 (33.3) | 8 (66.7) | 12 (100) |

| Unknown | 0 (0.0) | 21 (100) | 2 (100) |

| Total | 73 | 16 | 89 |

Factors favoring absence of peritoneal carcinomatosis in the patients with CT-defined ascites which was not yet determined whether malignant or not.

We tried to search factors favoring absence of peritoneal carcinomatosis in the gastric cancer patients with CT-defined ascites in the larger number of cases. The sex and age distributions in these 40 patients (BRM-SNU) were not statistically different from those of the initial 106 gastric cancer patients (BRM02).

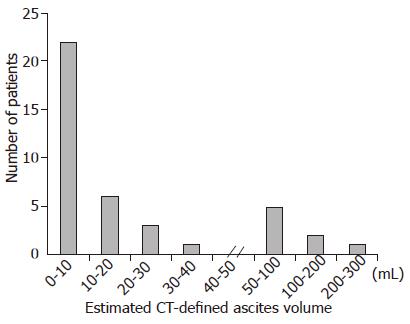

Majority of CT-defined ascites, of which the na-ture could not be preoperatively characterized, had vo-lumes of less than 10 mL with a left-skewed pattern (Skewness = 2.768, Figure 2). The range of volume was 1-300 mL; the mean was 34.8 mL and the median was 9.9 mL. Thirty-two cases were categorized as ‘minimal’ ascites and the rest eight were ‘mild’ ascites. Age and sex were not related to the volume of CT-defined ascites (data not shown), but the stage of cancer seemed lower in the patients with minimal ascites than those with mild ascites (Table 5).

| Stage | Minimal ascites (%) | Mild ascites (%) |

| 1 | 9 (28.1) | 0 (0) |

| 2 | 4 (12.5) | 1 (12.5) |

| 3 | 5 (15.6) | 1 (12.5) |

| 4 | 14 (43.8) | 6 (75.0) |

| Total | 32 (100) | 8 (100) |

The CT-defined ‘minimal’ ascites were associated with peritoneal carcinomatosis in only 12.5% and demonstrated surgically recovered ascites in only 9.4% (Table 6). These data confirmatively reproduced the results obtained from the fewer cases in BRM02 (Table 2, Table 3, Table 4). Contrary to the CT-defined ‘minimal’ ascites, the CT-defined ‘mild’ ascites were accompanied with peritoneal carcinomatosis in as high as 75%, and were proved to have genuine fluid collection in 62.5%.

In addition to the ascitic volume, several other factors suggestive of negative peritoneal carcinomatosis were tested by the univariate analysis in the patients with CT-defined minimal or mild ascites (Table 7). When enlargement of peritoneal lymph nodes were absent or confined to the regional perigastric area at the CT images, the negative predictive value for peritoneal carcinomatosis was 88.9%. Free of CT-defined perigastric invasion also negatively predicted peritoneal carcinomatosis in 90.9%. None of the patients with tumors with less than 3 cm were accompanied with malignant peritoneal seeding. However, except for the CT-defined ‘minimal’ ascites in comparison with the more abundant ascites, none of the above factors obtained statistical significance by multivariate analysis as an independent predictor for absence of malignant seeding.

| Peritoneal carcinomatosis Significance Predictive value | ||||

| Negative | Positive | |||

| CT-defined enlarged lymph node (L/N) | ||||

| None or Regional L/N | 24 | 3 | NPV: 88.9%1 | |

| Distant L/N | 6 | 7 | P<0.01 | |

| CT-defined perigastric invasion | ||||

| Negative | 20 | 2 | NPV: 90.9% | |

| Positive | 10 | 8 | P<0.05 | |

| Tumor size defined by endoscopy or UGIS | ||||

| <3 cm | 10 | 0 | NPV: 100% | |

| 3-10 cm | 16 | 6 | ||

| >10 cm | 4 | 4 | P<0.05 | |

| EGC vs AGC2 | ||||

| EGC | 7 | 0 | NPV: 100% | |

| AGC | 23 | 10 | NS | |

CT has been established as the most popular staging modality in gastric cancer although conventional or endoscopic ultrasonography, or laparoscopy can also be used[3,4,10-14]. The role of CT in detecting distant metastasis has been particularly well recognized; overall sensitivity for assessing liver metastasis reached about 62-89%[4,13,14].

However, CT is less reliable in identifying ascites or peritoneal carcinomatosis; the sensitivity was merely 36-46.7% for ascites and was 13-30% for malignant peritoneal seeding[4,12,14,15]. While the full blown peritoneal carcinomatosis demonstrating all the relevant radiologic features is diagnosed unambiguously, early and tiny malignant implantation cannot be easily decided. Although ascites has been regarded an important sign suggesting peritoneal carcinomatosis[5], the meaning of ascites may become ambiguous, as the dynamic CT detects subtle amounts of peritoneal fluid collection with increased sensitivity.

Then, what is the clinical significance of minimal ascites found in the CT image? Our data showed that minimal amounts of suspicious ascites defined by the dynamic CT were associated by peritoneal carcinomatosis in only 12.5-25%. This data may suggest that the patients need not hesitate to go through surgery, if the CT-defined minimal ascites is the only delusive clue for peritoneal seeding.

In the past, these amounts of minimal ascites might have never been detected by the CT and, therefore, might have never become a clinical issue. It may be argued whether the CT-defined minimal ascites is true or false-positive. However, this kind of question seems clinically out of point. Confirmation of real ascites may hardly be possible. Even surgery cannot be a gold standard in judging the presence of ascites because some blood or irrigated saline might be inevitably mixed with minimal, if any, ascites during surgery. Moreover, peritoneal cavity physiologically contains small amount of serous fluid which has been produced by permeable mesothelium[16], although this disperses diffusely in the peritoneal cavity and is not usually detected by the CT. It remains uncertain, if our CT-defined ‘minimal’ ascites is exaggerated physiologic fluid, or pathologic ascites.

On the other hand, high index of suspicion may have rendered observers to detect phantom radiologic ascites in the cancer patients. However, an article by Chen et al[17] also reported that small amounts of ascites were detected at the perigastric area in 39% of patients with gastric cancers by endoscopic ultrasonography and they were not significantly correlated with macroscopic peritoneal carcinomatosis. Revealing the mechanism in the development of minimal ascites may be beyond the scope of this study.

No matter whether CT-defined minimal ascites is true or false, the apparent existence of minimal ascites reasonably defined by the dynamic CT may confuse a physician in determining the patient’s operability. This may be particularly critical in the patients with marginally poor condition. It is possible that, for example, elderly patients may give up radical surgery, when they are imprudently suggested the worse prognosis, because of the suspicious ascites. Adoption of laparoscopic staging in patients with CT-defined minimal ascites is another issue. Although laparoscopic examination may reveal the nature of minimal ascites more clearly[12], this procedure is not always routinely available at every hospital. In the most common practice setting, a physician cannot help but judge the operability according to the CT finding and other clinical manifestations.

If CT-defined minimal ascites has just low probability of peritoneal carcinomatosis, what additional factors could enhance the possibility of free peritoneum? Of course, it should be explored first whether peritoneal nodules, fat strands, pleated soft tissue, thickening of omental, mesentery and/or bowel wall, or other radiologic clues for malignant seeding were accompanied with or not. As our data suggested, when CT-defined lymph node enlargements were not found beyond the regional gastric area, CT-defined perigastric invasions were not detected, and the size of tumor was less than 3 cm, the probability of true peritoneal carcinomatosis may be very low, at least based on the univariate analysis.

In conclusion, majority of malignancy-undetermined CT-defined minimal ascites that was estimated to be less than 50 mL at the preoperative phase are not significantly related to the peritoneal carcinomatosis. Therefore, if the peritoneal carcinomatosis was not definitely established, passive therapeutic strategy should not be applied to those patients simply because ascites is suspected. Definite meaning of CT-defined minimal ascites may need to be reinterpreted by the final effect on survival after long-term follow-up, and this study is under way.

We thank Dr. Yaron Niv for helpful discussion and critical reading of the manuscript; and Dr. Ajay Goel for editing the manuscript.

Science Editor Pravda J and Guo SY Language Editor Elsevier HK

| 1. | Plummer M, Franceschi S, Muñoz N. Epidemiology of gastric cancer. IARC Sci Publ. 2004;157:311-326. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Adachi Y, Kitano S, Sugimachi K. Surgery for gastric cancer: 10-year experience worldwide. Gastric Cancer. 2001;4:166-174. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 38] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Paramo JC, Gomez G. Dynamic CT in the preoperative evaluation of patients with gastric cancer: correlation with surgical findings and pathology. Ann Surg Oncol. 1999;6:379-384. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 13] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | D'Elia F, Zingarelli A, Palli D, Grani M. Hydro-dynamic CT preoperative staging of gastric cancer: correlation with pathological findings. A prospective study of 107 cases. Eur Radiol. 2000;10:1877-1885. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 98] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Yoshikawa T, Kanari M, Tsuburaya A, Kobayashi O, Sairenji M, Motohashi H. Clinical and diagnostic significance of abdominal CT for peritoneal metastases in patients with primary gastric cancer. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 2002;29:1925-1928. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Villanueva A, Pérez C, Sabaté JM, Llauger J, Giménez A, Sanchis E, García T, Moreno A. Peritoneal carcinomatosis. Review of CT findings in 107 cases. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 1995;87:707-714. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Nakajima T, Harashima S, Hirata M, Kajitani T. Prognostic and therapeutic values of peritoneal cytology in gastric cancer. Acta Cytol. 1978;22:225-229. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | Kodera Y, Nakanishi H, Yamamura Y, Shimizu Y, Torii A, Hirai T, Yasui K, Morimoto T, Kato T, Kito T. Prognostic value and clinical implication of disseminated cancer cells in the peritoneal cavity detected by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction and cytology. Int. J. Cancer. 1998;79:429-433. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Doust BD. The use of ultrasound in the diagnosis of gastroenterological disease. Gastroenterology. 1976;70:602-610. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Habermann CR, Weiss F, Riecken R, Honarpisheh H, Bohnacker S, Staedtler C, Dieckmann C, Schoder V, Adam G. Preoperative staging of gastric adenocarcinoma: comparison of helical CT and endoscopic US. Radiology. 2004;230:465-471. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 190] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 204] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lavonius MI, Gullichsen R, Salo S, Sonninen P, Ovaska J. Staging of gastric cancer: a study with spiral computed tomography, ultrasonography, laparoscopy, and laparoscopic ultrasonography. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2002;12:77-81. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 18] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Stell DA, Carter CR, Stewart I, Anderson JR. Prospective comparison of laparoscopy, ultrasonography and computed tomography in the staging of gastric cancer. Br J Surg. 1996;83:1260-1262. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 82] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Adachi Y, Sakino I, Matsumata T, Iso Y, Yoh R, Kitano S, Okudaira Y. Preoperative assessment of advanced gastric carcinoma using computed tomography. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:872-875. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 14. | Kayaalp C, Arda K, Orug T, Ozcay N. Value of computed tomography in addition to ultrasound for preoperative staging of gastric cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2002;28:540-543. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 30] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Nozoe T, Matsumata T, Sugimachi K. Usefulness of preoperative transvaginal ultrasonography for women with advanced gastric carcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:2509-2512. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 6] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Nance FC. Diseases of the peritoneum, retroperitoneum, mesentery, and omentum. Bockus Gastroenterology. 5th ed. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders 1995; 3061-3096. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 17. | Chen CH, Yang CC, Yeh YH. Preoperative staging of gastric cancer by endoscopic ultrasound: the prognostic usefulness of ascites detected by endoscopic ultrasound. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;35:321-327. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 42] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |