DEFINITION AND HISTORY

The term bezoar refers to an intraluminal mass in the gastrointestinal system caused by the accumulation of indigestible ingested materials, such as vegetables, fruits, and hair[1,2]. Called “panzehr” in Arabic and “padzhar” in Persian, the term means antidote[3]. Although there is written evidence of bezoars identified in animal and human gastrointestinal systems in the 10th century AD, the first scientific definition was made by Baudmant[1,2] with the publication of a case of trichobezoar in 1779. In 1854, Quain named the mass of intragastric food residue found at autopsy a “bezoar”. The first preoperative trichobezoar case was reported by Stelzner[4] in 1894.

Bezoars are named according to the material they are made of: a trichobezoar consists of hair; a phytobezoar of vegetable and fruit residues; a lactobezoar is formed from dairy products; a pharmacobezoar is caused by medications; and a polybezoar is caused by ingested foreign bodies[3,4]. In addition, Chintamani et al[5] identified biliary bezoars caused by bile stasis following hepatobiliary or gastric diversion surgery. The most common type of bezoar is the phytobezoar, which consists of indigestible food residue, such as cellulose and hemicellulose.

Trichobezoars are generally seen in individuals with trichophagia, a psychiatric disorder that usually occurs during childhood and in young adults. Trichobezoars are generally located in the stomach. However, if trichophagia is not noticed by the parents and if it becomes prolonged, then a condition called Rapunzel Syndrome can develop; it starts with hair in the stomach and the bezoar extends into the small intestine[3,4]. Since a psychiatric disorder underlies trichobezoar, recurrence is inevitable if insufficient psychiatric support is provided after surgical treatment[6]. Pharmacobezoars are usually caused by Kayexalate (sodium polystyrene sulfonate), cholestyramine, and antacid medications[7]. Lactobezoars generally occur in low-birth-weight newborns as a result of concentrated baby formulas[4].

CAUSES OF BEZOAR FORMATION

Bezoars are responsible for 0.4%-4% of cases of mechanical intestinal obstruction, although the true incidence is not known[8-10].

Previous gastric surgery

Gastric motility disorders and hypoacidity after gastric surgery are the basis of bezoar formation. Bezoars located in the stomach can pass through the small intestines easily and cause symptoms of intestinal obstruction, especially in patients with pyloric dysfunction after a pyloroplasty or wide gastrojejunostomy, resulting in a wide gastric outlet[3,11-13]. In a study of 42 diseases, Kement et al[14] reported that previous gastric surgery was the most important factor predisposing to bezoar formation, with a rate of 48%. In their series, Krausz et al[15] and Bowden et al[16] reported rates of 20% to 93%. Bezoar-associated ileus is more common in cases undergoing surgery for ulcer treatment, although this has become more rare with the introduction of proton pump inhibitors[16].

In patients who have had surgery for ulcer treatment, a vagotomy accompanied by a partial gastrectomy is the most important factor predisposing to bezoar formation[9-17]. A vagotomy and partial gastrectomy reduce gastric acidity, negatively affecting peptic activity. Furthermore, the antrum has an important role in the mechanical digestion of ingested food. The pylorus also prevents ingested food from passing through the small intestine as bolus, contributing to digestion. In this regard, the risk of bezoar formation was higher in patients who had a pyloroplasty and antrectomy[14,15]. The time taken for a bezoar to form after gastric surgery ranges from 9 mo to 30 years[15].

Bezoars can also form primarily in the small intestine when a mechanical factor alters the small intestinal passage, such as a diverticulum, stricture, or tumor[14,17]. Primary bezoars of the small intestine almost always cause intestinal obstruction. The most common location of obstruction is the terminal ileum[18].

High-fiber diet

High-fiber foods such as celery, pumpkins, grape skins, prunes, and especially persimmons are a risk factor for bezoar formation[14,15]. Persimmons, which means the “God of fruits” in Greek, are the fruit of plants in the genus Diospyros. Immature persimmons contain tannins, which form an adhesive-like substance when they encounter acids and hold other food residues, causing bezoar formation[14]. Krausz et al[15] and Erzurumlu et al[9] reported that 17% to 91% of bezoars in their series were caused by persimmons.

Other factors

Other factors predisposing to bezoar formation include systemic diseases such as hypothyroidism causing impaired gastrointestinal motility, postoperative adhesions, diabetes mellitus, Guillain-Barré syndrome, and myotonic dystrophy. Personal factors such as swallowing a large amount of food without sufficient chewing due to dental problems, especially in the elderly, the use of medications slowing gastrointestinal motility, and renal failure are also predisposing factors[4,19-21]. Erzurumlu et al[9] suggested that bezoar formation could occur without any predisposing factors.

CLINICAL FINDINGS

The clinical findings of bezoar-induced ileus do not differ from those of mechanical intestinal obstruction due to other causes. Almost all patients have poorly localized abdominal pain that is similar to ischemic pain. Other symptoms include abdominal distention, vomiting, nausea, a sense of satiety, dysphagia, anorexia, weight loss, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, and constipation[22,23].

It is generally difficult to determine whether bezoars are the clinical cause of ileus. The great majority of patients have a history of abdominal surgery, and adhesions following previous surgery are often responsible for ileus[24,25]. To reduce mortality and morbidity, it is important to consider bezoars in patients with a history of gastric surgery because the treatment of intestinal obstruction suspected of being induced by bezoars is mostly surgical. Prompt treatment can minimize the complications that might develop during medical follow-up.

DIAGNOSTIC METHODS

Recent advances in imaging methods have facilitated the diagnosis of ileus[24-27]. The air-fluid levels associated with mechanical intestinal obstruction can be seen on plain X-rays in most patients, but plain radiographs are not useful for differentiating other causes of ileus[27].

The appearance and localization of bezoars can be established with barium studies, which are effective for differentiating diverticular disease, intraluminal adenomas, primary malignancies of the small intestine causing mechanical obstruction, and bezoars[27,28]. However, these studies are not applicability in an emergency setting, can exacerbate peritonitis in the presence of perforation, and increase symptoms in complete obstruction[28].

Ultrasonography can detect the cause in 88%-93% of bezoar-induced ileus[28,29]. Typically, bezoars create hyperechoic acoustic shading on ultrasonography. However, the place of ultrasonography is controversial, since the examination is operator-dependent and requires experience. Furthermore, the air-fluid levels in the obstructed intestines block the view and ultrasonography has low sensitivity when there are multiple bezoars[30].

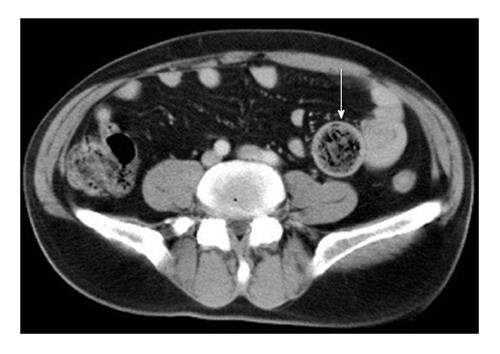

The most valuable method for determining the location and etiology of intestinal obstructions is contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) (Figure 1). The sensitivity and specificity of abdominal CT for bezoar-induced ileus are 90% and 57%, respectively[29,31]. Abdominal CT is effective for excluding other causes of intestinal obstruction. The advantages of CT are its ability to detect dilatation and edema in the intestinal loops, the presence of intra-abdominal free fluid, and the level of obstruction and development of strangulation[31]. Zissin et al[32] reported that a round, mottled intraluminal mass in the area of obstruction with dilated intestinal loops proximally and collapse distally was a pathognomonic CT finding for a bezoar resulting in ileus. Air bubbles might be seen within bezoars. When there are multiple bezoars, intraluminal bezoars distant from the area of obstruction area might go unnoticed if not sought carefully[28,31,32].

Figure 1 Intraluminal round bezoar and mottled gas pattern were seen in the jejenum segment.

Wall thickening due to inflammation were seen at the obstruction site (arrow).

Feces in the small bowel can appear similar to a bezoar radiologically and are seen in about 8% of the patients treated for intestinal obstruction[32]. Their radiological differentiation from bezoars is important because the treatment is generally medical. Small bowel feces generally appear in a longer segment than the bezoar and cause sharp-margin dilatation. Zissin et al[32] reported that the most evident radiological feature for differentiating a bezoar and small bowel feces was the longer transition zone of the feces-like view in the dilated segments proximal to the obstruction in small bowel feces compared to bezoar.

Preoperative CT assessment in patients with suspected intestinal obstruction induced by bezoars is helpful for determining the timing of surgery. When a bezoar is detected on CT, the surgery is generally performed within 48 h[31]. For small intestinal obstructions thought to result from non-bezoar causes, such as previous surgery, most patients can be treated medically, instead of surgically. A preoperative CT assessment allows the diagnosis of complications, such as perforation, necrosis, and ischemia secondary to bezoar-induced obstruction, and facilitates the planning of the timing of the surgical intervention[32].

TREATMENT

The initial treatment of bezoars causing obstruction is no different from that for obstructions of other etiologies. With intestinal obstruction, fluid deficiency and electrolyte imbalances result from vomiting and fluid accumulation within the intestinal segment. Therefore, the first step in treatment is intestinal decompression and fluid-electrolyte replacement[33].

The most common location of bezoars in the gastrointestinal system is the stomach, although gastric bezoars usually do not cause obstruction. Therefore, endoscopic methods have become the main treatment. Mechanical disintegration (mechanical lithotripter, large polypectomy snare, electrosurgical knife, drilling, laser destruction, and a Dormia basket for extraction) and chemical dissolution (saline solution, hydrochloric acid, sodium bicarbonate, and Coca-Cola lavage) methods have been described[33,34] Ladas et al[35] reported a very high success rate (90%) in gastric bezoars using a combination of mechanical and chemical methods. The treatment of choice is surgical for gastric bezoars in which endoscopic treatment failed.

Bezoar-induced intestinal obstructions occur mostly in the distal small intestine[35,36]. The greater width of the colon lumen reduces the possibility of colonic mechanical obstruction due to bezoars, although a few rare cases of colon obstruction have been reported in children[37,38].

Bezoar-induced intestinal obstructions usually occur 50-70 cm proximal to the ileocecal valve[9], because of the reduced lumen diameter towards the distal end, the lower motility in the distal small intestine, and the decreased motility of bezoars due to the increased water absorption at the distal end[36].

When surgical treatment is chosen, open or laparoscopic abdominal exploration may be performed[39]. Laparoscopic exploration is currently used more frequently; however, it requires technical experience because of the presence of dilated intestinal segments. It also requires a good preoperative radiological study to localize the bezoar because there can be multiple bezoars and there are reports of cases requiring surgery for an unnoticed bezoar[40]. The factors to be considered when selecting the laparoscopic method include the size and number of bezoars, the presence of complications (such as perforation and peritonitis), and previous abdominal operations[39,41]. In a study of 24 diseases, Yau et al[42] reported that the laparoscopic method had more advantageous outcomes when used in selected patients compared to the open method in terms of operating time, complication rates, and duration of hospital stay. Nirasawa et al[43] reported treatment outcomes with the laparoscopic method in patients with gastric bezoars and Son et al[44] reported such outcomes in patients with gastric bezoars that could not be treated endoscopically. Fraser and Song emphasized that the laparoscopic technique might be used safely in selected patients with giant gastric bezoars[45,46]. Son et al[44] discussed the risk of intra-abdominal contamination and the location of the gastric incision as the points to be considered for laparoscopic gastric bezoar surgery.

Laparoscopic interventions are being performed increasingly; however, open surgery is still the most common method used for the surgical treatment of bezoar-induced intestinal obstructions. The review by Gorter et al[47] reported that laparotomy intestinal bezoar treatment was successful in more than 100 studies.

After determining the need for surgical intervention, the issue of what kind of intervention should be performed arises. The decision to perform an enterotomy to remove bezoars varies with experience[9]. Surgeons often use the milking technique, which is used to advance the intestinal contents manually either proximally or distally. However, a laceration in the intestinal serosa or mesentery can occur during this procedure[36,39]. Aysan et al[48] reported that rats undergoing milking developed significantly more peritoneal adhesions compared to the control group and that the peritoneal cultures were positive.

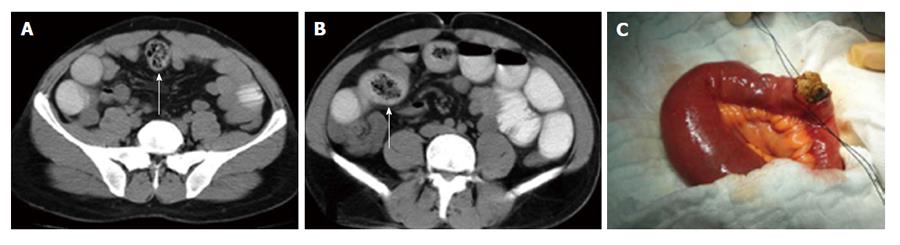

The bezoar location in the gastrointestinal system (duodenum, jejunum, or ileum) plays an important role in selecting the surgical method (Figure 2). Oh et al[49] reported that an enterotomy was more successful for bezoars located in the proximal small intestine. For the patients with ischemia and perforation caused by bezoars, anastomosis or stoma procedures should be performed with segmental small bowel resection[49-52].

Figure 2 A 62-year-old male patient.

Multiple small bowel bezoars which have round or irregular shape and mottled gas pattern were detected on abdominal computed tomography (A and B; arrows). Intraoperative finding (C); an irregular shaped bezoar which caused intestinal obstruction was removed via enterotomy, dilated proximal segments and non-dilated distal segments are visible.

In conclusion, the possibility of bezoars must be considered in patients with mechanical intestinal obstruction, although they are rare. This possibility must be considered especially in regions where there is excess consumption of high-fiber food, which causes bezoar formation, in patients with intestinal obstruction, and in patients who have a history of abdominal surgery for a peptic ulcer. Early preoperative contrast-enhanced CT assessment aids both the diagnosis and decision for early surgical treatment. Surgery is usually chosen for bezoars causing intestinal obstruction. In addition to the physical characteristics of the bezoar, its location should be considered when selecting the surgical procedure.

P- Reviewer: Milone M, Rosales-Reynoso MA, Touil-Boukoffa C S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu SQ