Published online Apr 28, 2016. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v8.i4.370

Peer-review started: April 4, 2015

First decision: August 31, 2015

Revised: January 23, 2016

Accepted: March 4, 2016

Article in press: March 9, 2016

Published online: April 28, 2016

Transperineal ultrasound is an inexpensive, safe and painless technique that dynamically and non-invasively evaluates the anorectal area. It has multiple indications, mainly in urology, gynaecology, surgery and gastroenterology, with increased use in the last decade. It is performed with conventional probes, positioned directly above the anus, and may capture images of the anal canal, rectum, puborectalis muscle (posterior compartment), vagina, uterus, (central compartment), urethra and urinary bladder (anterior compartment). Evacuatory disorders and pelvic floor dysfunction, like rectoceles, enteroceles, rectoanal intussusception, pelvic floor dyssynergy can be diagnosed using this technique. It makes a dynamic evaluation of the interaction between pelvic viscera and pelvic floor musculature, with images obtained at rest, straining and sustained squeezing. This technique is an accurate examination for detecting, classifying and following of perianal inflammatory disease. It can also be used to sonographically guide drainage of deep pelvic abscesses, mainly in patients who cannot undergo conventional drainage. Transperineal ultrasound correctly evaluates sphincters in patients with fecal incontinence, postpartum and also following surgical repair of obstetric tears. There are also some studies referring to its role in anal stenosis, for the measurement of the anal cushions in haemorrhoids and in chronic anal pain.

Core tip: Transperineal ultrasound is a technique that has multiple applications, mainly in urology, gynaecology and gastroenterology. Obstructed defecation, inflammatory perianal diseases and fecal incontinence are the principal indications in gastroenterology, but this technique remains almost unknown to most gastroenterologists. It allows for dynamic evaluation of the structures interaction during defecation stimulation manoeuvres, as well as the identification, classification, and follow-up in inflammatory perianal disease, and it can also identify sphincter injury in fecal incontinence. In this review the technique is described and the current evidence that supports its use in several areas is also discussed.

- Citation: Albuquerque A, Pereira E. Current applications of transperineal ultrasound in gastroenterology. World J Radiol 2016; 8(4): 370-377

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8470/full/v8/i4/370.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4329/wjr.v8.i4.370

Pelvic floor ultrasonography includes several different techniques, namely, transvaginal sonography (TVS), endoanal ultrasound (EAUS) and transperineal ultrasound (TPUS)[1], using 2-dimensional (2D) or 3-dimensional (3D) imaging. All of these techniques are important for the evaluation of the functional anatomy of the pelvic floor[2].

TPUS was initially proposed for the examination of the ano-rectal region since 1983 in neonates with imperforate anus[3] and later, other studies have also described the importance of this examination for the assessment of this area[4].

This is a simple, accessible, inexpensive, safe and painless technique that dynamically and non-invasively evaluates anorectal structures. It has multiple indications mainly in urology, gynaecology, surgery and gastroenterology, with increased use in the last decade[5]. It is normally performed with conventional probes, positioned directly above the anus, and may capture images of the anal canal, rectum, puborectalis muscle, vagina, uterus, urethra and urinary bladder.

Patient evaluation does not require specific preparation and is performed using a conventional probe, usually a curved array with frequencies between 3.5-6 MHz. The probe is covered with gel and with a non-powdered glove for hygienic purposes. Powdered gloves should not be used due to possible reverberations of the image quality[6,7].

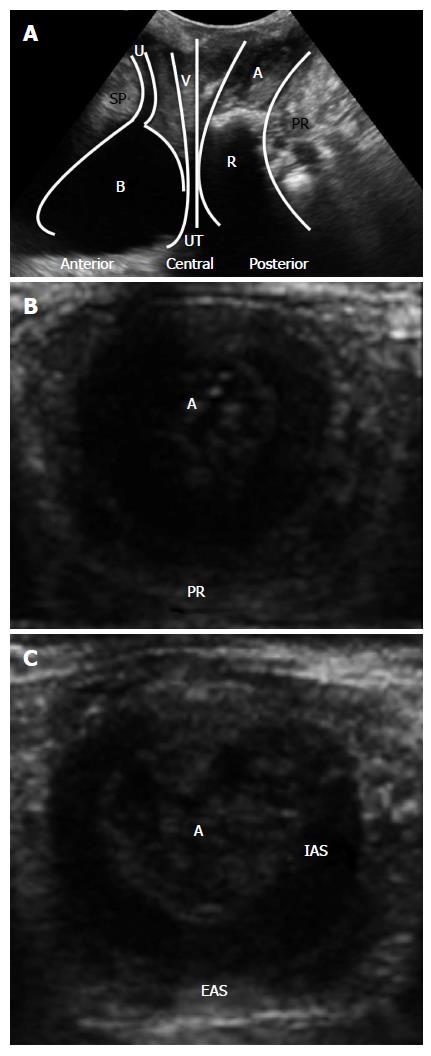

The technique can be performed in the left lateral position or in the dorsal lithotomy position. Prior voiding is usually preferable[6,7], but for the anterior compartment, bladder filling is useful. The probe is positioned above the anus, in the midsagital plane and the examination is initiated with the curved array probe for a more generic evaluation (Figure 1A). For better orientation, some operators prefer to identify the structures and subsequently assess the sphincter complex with a high-resolution linear probe (7-10 MHz) (Figure 1B and C). 3D- and four-dimensional (4D) TPUS may be used.

In patients with perianal fistulas, the probe is placed in the external orifice to follow the fistula to the internal orifice. Cannulation and instillation with hydrogen peroxide will improve the assessment.

There are different possibilities on image orientation, and in the literature several options were described. The most used is the original orientation with cranioventral aspects to the left and dorsocaudal to the right[6,7].

The standard midsagittal view in women includes the symphysis anteriorly, the urethra and bladder neck (anterior compartment), the vagina, cervix (central compartment), rectum and anal canal (posterior compartment). The puborectalis muscle is a hyperechogenic area, posterior to the anorectal junction. It is possible to measure the anorectal angle (ARA) and to evaluate the integrity of the perineal body and of the rectovaginal septum.

In TPUS, it is important to assess all three compartments (Figure 1A).

Anterior compartment: There are two important structures in this compartment, the urethra and the bladder.

The urethra is a vertical hypoechoic area, with the urethral rhabdosphincter surrounding it appearing as a double hyperechoic stripe. In continuity with the urethra is the bladder that is also a hypoechoic structure.

This technique is important in the anatomical, physiological and pathological evaluation of the urethra and the bladder, namely, for the diagnosis of cystocele and the assessment of bladder neck mobility, bladder wall thickness and residual urine. It can also be important in the diagnosis of urethral diverticulum, bladder foreign bodies and bladder tumours[6].

Concerning cystocele, TPUS can be very helpful in diagnosing and classifying the type of cystocele (different types have different functional implications)[6].

Central compartment: This compartment includes the vagina and the uterus in women. Due to its isoechoic nature, the uterus can be difficult to identify especially in postmenopausal women with atrophic uterus[6].

TPUS can demonstrate uterovaginal prolapse[6,7], explaining symptoms of voiding dysfunction in an enlarged retroverted uterus or symptoms of obstructed defecation in an anteverted uterus, which is compressing the anorectum[6].

Posterior compartment: TPUS is important for anorectal evaluation in three areas: Obstructed defecation, perianal inflammatory disease and fecal incontinence.

Obstructed defecation: Chronic constipation is a common problem that affects 2%-30% of people in the Western world and 30%-50% suffer from obstructed defecation syndrome (ODS)[8,9]. Obstructed defecation can be functional or mechanical. Functional disturbances include dyssynergia and inadequate defecatory propulsion[10,11]. The mechanical type includes rectocele, enterocele and intussusception[12].

TPUS can be used in the diagnosis of these evacuatory disorders and pelvic floor dysfunction.

The need for preparation before the examination is a matter of debate; some studies do not include any preparation[13-16], but, in others, the patient’s rectum is filled with ultrasonographic coupling gel and gel is also instilled into the vagina. The ingestion of Gastrografin® diluted in water can also improve small bowel visualization[17-19].

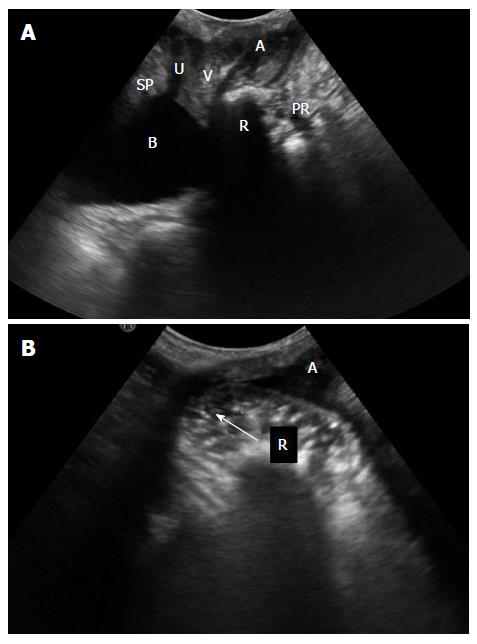

The images are obtained at rest, straining and sustained squeezing. A rectocele is a herniation of the anterior rectal wall into the vagina (Figure 2). On ultrasound, rectocele depth is measured perpendicular to a line projected along the expected contour of the anterior rectal wall[14,15]. Diagnosis is made if herniation is at least 10 mm in depth[20,21].

An enterocele is defined as a hernia, normally of the small bowel (enterocele) or sigmoid colon (sigmoidocele), into the Douglas pouch, vagina or between the rectum and the vagina. It is normally associated with other pelvic floor disorders. These patients tend to have a longer history of constipation and a prior hysterectomy[19].

For ultrasound, there is no standardized method for describing rectoceles and enteroceles. Some studies[13,22] classify rectocele as it has been previously defined in defecography: Small (first degree) if < 2 cm in depth, moderate (second degree) if 2-4 cm in depth, and large (third degree) if more than 4 cm in depth[23]. Enterocele can be graded as small (grade 1), when the most distal part descends into the upper third of the vagina; moderate (grade 2), when it descends into the middle third of the vagina; or large (grade 3), when it descends into the lower third of the vagina.

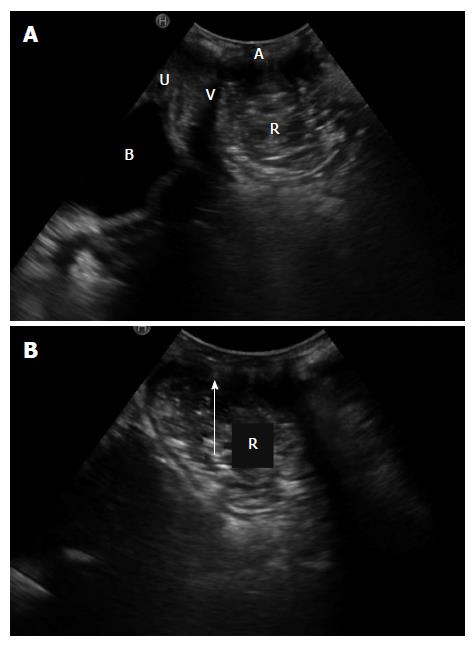

Rectal intussusception is defined as an invagination of the rectal wall into the rectum or anus (Figure 3). It is a common finding on defecography and is present in up to 50% of asymptomatic subjects[24,25]. When the invagination is ≥ 3 mm thick and a cause of obstructed defecation, it can have clinical relevance[24].

The ARA should be calculated at the point of convergence of the longitudinal axis of the anal canal with the posterior margin of the rectal wall. During evacuation there is a characteristic widening of the posterior ARA[17] and the puborectalis muscle is considered dyssynergic when the ARA does not open during straining.

There are several studies comparing dynamic TPUS (D-TPUS) with defecography in evacuatory dysfunction, with conflicting results.

Concerning enterocele, most studies showed a good agreement between methods[15,18,19,22], with TPUS revealing a high predictive value for diagnosis. Weemhoff et al[16] showed, however, that the diagnostic quality of TPUS was limited compared to evacuation proctography, with many false-positive results.

For rectocele and intussusception diagnosis, higher and lower agreements have been described. For retocele, Cohen’s kappa concordance index values vary between low 0.26[14] and high 0.88[19], and also for intussusception Cohen’s kappa values vary between low 0.09[14] and high 0.88-0.9[13,19]. These differences may be explained by the use of contrast medium, selection and position of the patient, type of probe used and the experience of the operators[22]. After injection of ultrasound contrast medium into the rectum, higher agreements for the detection of rectocele and intussusception were described[18,19]. In 2008, Perniola et al[14] showed that this agreement was poor for rectocele and intussusception, but when previously diagnosed on ultrasound these results were highly predictive of findings on defecation proctography, notwithstanding low negative predictive values. When ultrasound failed to detect rectocele or rectal intussusception, defecation proctography frequently showed abnormalities. Ultrasound may be important as an initial examination, although negative findings may require confirmation.

Most of the studies showed a good agreement between TPUS and defecography in the measurement of puborectalis contraction and the ARA[13,17,18,22]. However, Perniola et al[14] showed that there was a poor agreement for ARA measurements. Another study revealed that the difference between the techniques almost achieved significance for ARA measurement during straining, with markedly greater widening of the ARA noted during defecography. This may be explained by the position adopted for examination using D-TPUS that is likely to lead to a higher resting ano-rectal junction position and less descent on straining. In addition, maintaining the probe contact with the perineum may limit the pelvic floor movement[18].

Defecography is relatively poorly tolerated and exposes the patient to radiation. TPUS is fast, inexpensive, non-invasive, much better tolerated and without radiation. However, as previously described, it has several limitations. Ultrasound is highly operator dependent and the evacuation phase is not fully reproducible with D-TPUS.

Concerning dynamic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), it has several advantages, such as the lack of radiation and a better visualization of the anal sphincter (with endoanal MRI) and soft tissues surrounding the rectum and anal canal; however, it is expensive and not widely available[17].

Inflammatory perianal disease: TPUS is an accurate examination for diagnosing, classifying and managing perianal fistulas and abscesses.

Perianal fistulas can be classified according to their nature or relationship with the sphincter. Concerning the nature, there are two major types of fistulas: Cryptoglandular (90% of the cases) or related with inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), mainly Crohn’s disease (10% of the cases). Regarding the relationship with the sphincter, Park’s classification is one of the most used systems, classifying fistulas into 5 types: Superficial, intersphincteric, transphincteric, extrasphincteric or suprasphincteric. This classification has several limitations, specifically it does not include important information about perianal disease. The American Gastroenterological Association[26] developed another classification based on anatomical and clinical parameters, classifying fistulas as “simple” or “complex”. Simple fistulas are low, with a single external opening, without pain or fluctuation to suggest perianal abscess, and without evidence of a rectovaginal fistula or anorectal stricture. Complex fistulas are high, have multiple external openings, are associated with the presence of pain or fluctuation to suggest a perianal abscess, and are associated with rectovaginal fistula, anorectal stricture or active rectal disease at endoscopy. Patients with complex fistulas have a higher risk of fecal incontinence after surgery, worse healing and higher risk of recurrence, so the precise description of a fistula tract is mandatory.

In cases of inflammatory perianal disease, TPUS can overcame several limitations of EAUS, such as pain that does not allow for probe introduction, in cases of anal strictures and also the focal limitation of EAUS. TPUS can be a useful complementary technique to MRI given its advantages in detecting anovaginal and rectovaginal fistulae and some superficial lesions. It can also be used in patients with metallic clips or claustrophobia. Thus, TPUS combines the high resolution and real time capabilities of EAUS and the panoramic view generated by MRI[27].

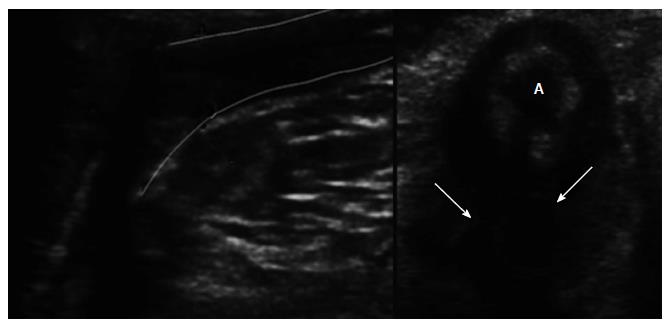

Fistulas are hypoechoic linear areas or fluid-containing tubular areas and TPUS has a > 85% sensitivity in fistula classification and a positive predictive value of 86.5%[28]. Instillation with hydrogen peroxide can improve their visualization. Abscesses are larger oval hypoecogenic structures, most often associated with a fistulous tract (Figure 4). TPUS has a 90% to 95% sensitivity for the identification of the internal orifice[27,29,30], which is suggested by a hypoechoic image at the subepithelial or intersphincteric space with internal sphincter disruption.

Studies published by Wedemeyer et al[27] and Maconi et al[28,31] showed that TPUS has a high sensitivity and specificity in detecting perianal disease comparable to those of MRI and EAUS. A study by Rasul et al[32] showed that TPUS can be used to follow perianal fistulas in Crohn’s disease patients, concerning therapeutic response. In this study, therapeutic response to infliximab in patients with perianal Crohn’s disease was monitored by TPUS. This technique can be used as a simple tool to monitor therapeutic response, to guide biologic therapy suspension in cases of abscess and to evaluate complete healing. A recent paper by Hwang et al[33] revealed that TPUS can also be used in paediatric perianal Crohn’s disease evaluation.

In ulcerative colitis TPUS can be used to assess the wall of the distal rectum and anorectal junction in the setting of an assessment of a perianal fistula and the function of the pouch-anal anastomosis in patients with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis in whom obstructed defecation and fecal incontinence have developed. Pouchitis may be revealed by subtle wall thickening in the pouch and a large volume of fluid feces within its lumen[34].

The two major limitations are related to poor penetration below 5-6 cm, not allowing for a good evaluation of the structures that are away from the probe (extrasphincteric and suprasphincteric tracts), and also in the evaluation of some superficial lesions, when gas is present in the lesions or anal folds. Moreover, it has limitations in differentiating active from inactive fistulas and active fistulas from collections.

TPUS can also be used to sonographically guide drainage of deep pelvic abscesses, mainly in patients who cannot undergo conventional transabdominal, transvaginal, or transrectal catheter drainage[35,36]. This approach offers a short, safe and direct route to deep pelvic fluid collections and is associated with a high success rate[36]. Sperling et al[36] performed a study including 12 patients with deep pelvic abscesses that were submitted to TPUS guided drainage. Transperineal needle placement was successful in all patients and clinical success was achieved in 9 out of 10 patients with no complications.

In a study evaluating the accuracy of combined transperineal and color Doppler sonography in the detection and characterization of perianal inflammatory disease, Mallouhi et al[37] showed that although color Doppler sonography did not improve the sensitivity and specificity for detecting perianal abscesses and fistulas, the presence of pathologic vascular structures in the peripheries of the abscesses and fistulas supported the findings shown on gray scale sonography and thus improved the operator’s diagnostic confidence and was highly predictive for the presence of a perineal inflammatory disease.

Fecal incontinence: In TPUS, in the coronal plane, the anal mucosa has a hyperechogenic star shape, and the internal anal sphincter (IAS) is a hypoechogenic structure surrounded by the external anal sphincter (EAS) that is hyperechogenic (Figure 1C).

The most common cause of fecal incontinence is obstetric anal sphincter injury. Sphincter evaluation is normally performed by EAUS. Studies with EAUS showed that one third of women have occult anal sphincter injury after first vaginal delivery[38] and that endosonography reveals sphincter defects after primary repairs in 54% to 93% of women[39-42].

In 2014, Shek et al[43] published a retrospective observational study (141 women) to evaluate the prevalence of residual defects of EAS after primary repair of obstetric anal sphincter injury using 4D TPUS and to correlate sonographic findings of residual defects and levator avulsion with significant symptoms of anal incontinence. A residual defect was found in 40% of the cases and levator avulsion in 19%. Both were found to be independent risk factors for fecal incontinence. This study had several limitations, namely, the IAS was not accessed, short follow-up period of two months and a lack of comparison with EAUS.

Obstetric tears are divided into several subclasses: Injury to the perineal skin (grade 1); injury to the perineum involving the perineal muscles (grade 2); involvement of the anal sphincter < 50% EAS (grade 3a); > 50% EAS (grade 3b); involvement of the IAS (grade 3c); involvement of the anal sphincter as well as the anorectal epithelium (grade 4)[44,45]. Early recognition, particularly during the immediate postpartum period, and surgical repair are fundamental to reduce later anal incontinence[46].

Four ultrasonographic signs indicative of damage after repair were defined as EAS or IAS sphincter discontinuity, thickening of the EAS at the 12-o’clock position, thinning of the IAS in the area of rupture in conjunction with thickening opposite the rupture site (the “half-moon” sign), and abnormality of the mucous folds[47,48].

The PREDICT[49] study revealed that 2D TPUS had a sensitivity and specificity of 64% and 85%, respectively, for detecting sphincter defect when compared with EAUS. TPUS can be useful in identifying normality, but not sensitive enough to identify an underlying sphincter defect in women following obstetric anal sphincter injury and/or presenting postpartum with symptoms of fecal incontinence. In this study, TPUS revealed to be difficult in analysing the distal levels of the anal sphincter complex. Furthermore, it is sometimes difficult to visualize the posterior and lateral parts of the EAS. This, however, is of relatively minor importance as the focus in this group of patients is on the anterior part of the anal sphincter. Other studies have confirmed the low sensitivity of 2D TPUS when compared with EAUS[50]. Nevertheless, a study by Roche et al[51] compared the two techniques, showing that they are comparable in detecting sphincter defects, mainly in the EAS.

Oom et al[52] conducted a study comparing 3D TPUS with 2D EAUS for detection of sphincter defects in women with fecal incontinence, revealing a good agreement between the two techniques.

There are several studies showing that 3D TPUS is an accessible, inexpensive and confortable method, allowing good sphincter evaluation in the postpartum period and also following surgical repair[47,48,53]. This technique has a multiplanar image, more precise volume calculation, and shorter examination period, with a possibility for a second opinion consultation, without the presence of the patient[47]. Nonetheless, most of these studies have an important limitation because authors did not perform a direct comparison of the 3D-TPUS images with the currently considered gold standard, EAUS.

Anal canal stenosis can be primary due to congenital malformations (rare) or secondary to IBD, overly extensive haemorrhoidectomy, radiation therapy or trauma. The most important information regarding anal stenosis is length and level of the stenosis and the status of the anal sphincters. Proctological examination and EAUS are often unfeasible or very difficult to perform even under local or general anestesia. In a study by Kolodziejczak et al[54] including four cases of patients with anal stenosis, 3D TPUS was used to provide detailed information on the length and level of stenosis and upon the integrity of the anal sphincters. Further studies are needed to confirm if TPUS can be used to evaluate anal stenosis and possibly plan optimal surgical treatment.

Visualization of the anal cushions was previously described using TVS[55,56]. In a study by Zbar et al[57] TPUS performed with a linear probe was used to measure the anal cushion area in a group of patients with internal haemorrhoids. Anal cushion area was measured by subtracting the luminal diameter of the undisturbed mid anal canal from the inner border of the IAS. In this study, there was a significant difference between normal subjects, patients with symptomatic haemorrhoids and after haemorrhoidectomy. TPUS can be useful for an objective assessment of internal haemorrhoids, although it does not provide clinical benefit in cases with a substantial external haemorrhoidal component, nor has a real role in the therapeutic decision, where generally larger and more symptomatic haemorrhoids are treated operatively[57].

In a study by Beer-Gabel et al[58] static and D-TPUS and EAUS were used to evaluate a cohort of patients presenting with previously undiagnosed chronic anal pain (> 3 mo duration with no clinical anorectal signs). In 25% of the cases occult intersphincteric sepsis was detected. EAUS and TPUS are important techniques, to exclude organic causes of anorectal pain.

TPUS is an important technique for uro-gynaecologic and ano-rectal evaluation. Obstructed defecation, inflammatory perianal diseases and fecal incontinence are the principal indications in gastroenterology.

D-TPUS evaluates structure interaction during defecation stimulation manoeuvres. In patients with ODS and ultrasound positive findings other examinations can be possibly avoided. In inflammatory perianal disease it identifies, classifies, and evaluates complications, as well as monitors response to treatment. In fecal incontinence, it can identify sphincter injury in the postpartum period and also following surgical repair of obstetric tears, especially with 3D. TPUS may possibly be seen as an extension of the ano-rectal examination.

P- Reviewer: Hennemann J, Santoro GA S- Editor: Kong JX L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Jiao XK

| 1. | Santoro GA, Wieczorek AP, Dietz HP, Mellgren A, Sultan AH, Shobeiri SA, Stankiewicz A, Bartram C. State of the art: an integrated approach to pelvic floor ultrasonography. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2011;37:381-396. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 165] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 123] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Valsky DV, Yagel S. Three-dimensional transperineal ultrasonography of the pelvic floor: improving visualization for new clinical applications and better functional assessment. J Ultrasound Med. 2007;26:1373-1387. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Oppenheimer DA, Carroll BA, Shochat SJ. Sonography of imperforate anus. Radiology. 1983;148:127-128. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 33] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Maconi G, Porro GB. Ultrasound of the gastrointestinal tract. 2nd ed. Springer, 2014. . [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Son JK, Taylor GA. Transperineal ultrasonography. Pediatr Radiol. 2014;44:193-201. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 18] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Dietz HP. Pelvic floor ultrasound: a review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202:321-334. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 188] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 197] [Article Influence: 14.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Dietz HP. Ultrasound imaging of the pelvic floor. Part I: two-dimensional aspects. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2004;23:80-92. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 255] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 210] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lembo A, Camilleri M. Chronic constipation. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1360-1368. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 564] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 495] [Article Influence: 23.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Surrenti E, Rath DM, Pemberton JH, Camilleri M. Audit of constipation in a tertiary referral gastroenterology practice. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:1471-1475. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Bharucha AE, Wald A, Enck P, Rao S. Functional anorectal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1510-1518. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 405] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 321] [Article Influence: 17.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Wald A, Bharucha AE, Cosman BC, Whitehead WE. ACG clinical guideline: management of benign anorectal disorders. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:1141-1157; (Quiz) 1058. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 212] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 177] [Article Influence: 17.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ellis CN, Essani R. Treatment of obstructed defecation. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2012;25:24-33. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 32] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Grasso RF, Piciucchi S, Quattrocchi CC, Sammarra M, Ripetti V, Zobel BB. Posterior pelvic floor disorders: a prospective comparison using introital ultrasound and colpocystodefecography. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2007;30:86-94. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 23] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Perniola G, Shek C, Chong CC, Chew S, Cartmill J, Dietz HP. Defecation proctography and translabial ultrasound in the investigation of defecatory disorders. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008;31:567-571. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 81] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Steensma AB, Oom DM, Burger CW, Schouten WR. Assessment of posterior compartment prolapse: a comparison of evacuation proctography and 3D transperineal ultrasound. Colorectal Dis. 2010;12:533-539. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 62] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Weemhoff M, Kluivers KB, Govaert B, Evers JL, Kessels AG, Baeten CG. Transperineal ultrasound compared to evacuation proctography for diagnosing enteroceles and intussusceptions. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2013;28:359-363. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 13] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Beer-Gabel M, Teshler M, Barzilai N, Lurie Y, Malnick S, Bass D, Zbar A. Dynamic transperineal ultrasound in the diagnosis of pelvic floor disorders: pilot study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:239-245; discussion 245-248. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 126] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Beer-Gabel M, Teshler M, Schechtman E, Zbar AP. Dynamic transperineal ultrasound vs. defecography in patients with evacuatory difficulty: a pilot study. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2004;19:60-67. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 80] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Beer-Gabel M, Assoulin Y, Amitai M, Bardan E. A comparison of dynamic transperineal ultrasound (DTP-US) with dynamic evacuation proctography (DEP) in the diagnosis of cul de sac hernia (enterocele) in patients with evacuatory dysfunction. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2008;23:513-519. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 55] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Dietz HP, Korda A. Which bowel symptoms are most strongly associated with a true rectocele? Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2005;45:505-508. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 74] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Dietz HP, Steensma AB. Posterior compartment prolapse on two-dimensional and three-dimensional pelvic floor ultrasound: the distinction between true rectocele, perineal hypermobility and enterocele. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2005;26:73-77. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 114] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Martellucci J, Naldini G. Clinical relevance of transperineal ultrasound compared with evacuation proctography for the evaluation of patients with obstructed defaecation. Colorectal Dis. 2011;13:1167-1172. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 34] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kelvin FM, Maglinte DD. Dynamic evaluation of female pelvic organ prolapse by extended proctography. Radiol Clin North Am. 2003;41:395-407. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 36] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Weiss EG, McLemore EC. Functional disorders: rectoanal intussusception. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2008;21:122-128. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Shorvon PJ, McHugh S, Diamant NE, Somers S, Stevenson GW. Defecography in normal volunteers: results and implications. Gut. 1989;30:1737-1749. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 26. | American Gastroenterological Association Clinical Practice Committee. American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement: perianal Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1503-1507. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 27. | Wedemeyer J, Kirchhoff T, Sellge G, Bachmann O, Lotz J, Galanski M, Manns MP, Gebel MJ, Bleck JS. Transcutaneous perianal sonography: a sensitive method for the detection of perianal inflammatory lesions in Crohn’s disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:2859-2863. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 46] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 33] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Maconi G, Ardizzone S, Greco S, Radice E, Bezzio C, Bianchi Porro G. Transperineal ultrasound in the detection of perianal and rectovaginal fistulae in Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2214-2219. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 66] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Zbar AP, Oyetunji RO, Gill R. Transperineal versus hydrogen peroxide-enhanced endoanal ultrasonography in never operated and recurrent cryptogenic fistula-in-ano: a pilot study. Tech Coloproctol. 2006;10:297-302. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 14] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Domkundwar SV, Shinagare AB. Role of transcutaneous perianal ultrasonography in evaluation of fistulas in ano. J Ultrasound Med. 2007;26:29-36. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 31. | Maconi G, Tonolini M, Monteleone M, Bezzio C, Furfaro F, Villa C, Campari A, Dell-Era A, Sampietro G, Ardizzone S. Transperineal perineal ultrasound versus magnetic resonance imaging in the assessment of perianal Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:2737-2743. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 38] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Rasul I, Wilson SR, MacRae H, Irwin S, Greenberg GR. Clinical and radiological responses after infliximab treatment for perianal fistulizing Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:82-88. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 67] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Hwang JY, Yoon HK, Kim WK, Cho YA, Lee JS, Yoon CH, Lee YJ, Kim KM. Transperineal ultrasonography for evaluation of the perianal fistula and abscess in pediatric Crohn disease: preliminary study. Ultrasonography. 2014;33:184-190. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 11] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Tonolini M, Maconi G. Imaging of Perianal Inflammatory Diseases. Milan: Springer 2013; . [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 35. | Lorentzen T, Nolsøe C, Skjoldbye B. Ultrasound-guided drainage of deep pelvic abscesses: experience with 33 cases. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2011;37:723-728. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Sperling DC, Needleman L, Eschelman DJ, Hovsepian DM, Lev-Toaff AS. Deep pelvic abscesses: transperineal US-guided drainage. Radiology. 1998;208:111-115. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 33] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Mallouhi A, Bonatti H, Peer S, Lugger P, Conrad F, Bodner G. Detection and characterization of perianal inflammatory disease: accuracy of transperineal combined gray scale and color Doppler sonography. J Ultrasound Med. 2004;23:19-27. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 38. | Sultan AH, Kamm MA, Hudson CN, Thomas JM, Bartram CI. Anal-sphincter disruption during vaginal delivery. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1905-1911. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1281] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 966] [Article Influence: 31.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Sultan AH, Kamm MA, Hudson CN, Bartram CI. Third degree obstetric anal sphincter tears: risk factors and outcome of primary repair. BMJ. 1994;308:887-891. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 583] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 483] [Article Influence: 16.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Poen AC, Felt-Bersma RJ, Strijers RL, Dekker GA, Cuesta MA, Meuwissen SG. Third-degree obstetric perineal tear: long-term clinical and functional results after primary repair. Br J Surg. 1998;85:1433-1438. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 141] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Nielsen MB, Hauge C, Rasmussen OO, Pedersen JF, Christiansen J. Anal endosonographic findings in the follow-up of primarily sutured sphincteric ruptures. Br J Surg. 1992;79:104-106. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 76] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Starck M, Bohe M, Valentin L. The extent of endosonographic anal sphincter defects after primary repair of obstetric sphincter tears increases over time and is related to anal incontinence. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2006;27:188-197. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 55] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 43. | Shek KL, Guzman-Rojas R, Dietz HP. Residual defects of the external anal sphincter following primary repair: an observational study using transperineal ultrasound. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2014;44:704-709. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 41] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Sultan AH. Editorial: Obstetric perineal injury and anal incontinence. Clin Risk. 1999;5:193-196. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 45. | Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG). The Management of Third- and Fourth- Degree Perineal Tears. RCOG Guideline 2007 (revised). 2007;29:1-11. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 46. | Faltin DL, Boulvain M, Floris LA, Irion O. Diagnosis of anal sphincter tears to prevent fecal incontinence: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:6-13. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 105] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Valsky DV, Messing B, Petkova R, Savchev S, Rosenak D, Hochner-Celnikier D, Yagel S. Postpartum evaluation of the anal sphincter by transperineal three-dimensional ultrasound in primiparous women after vaginal delivery and following surgical repair of third-degree tears by the overlapping technique. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2007;29:195-204. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 33] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Valsky DV, Cohen SM, Lipschuetz M, Hochner-Celnikier D, Yagel S. Three-dimensional transperineal ultrasound findings associated with anal incontinence after intrapartum sphincter tears in primiparous women. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2012;39:83-90. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 25] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Roos AM, Abdool Z, Sultan AH, Thakar R. The diagnostic accuracy of endovaginal and transperineal ultrasound for detecting anal sphincter defects: The PREDICT study. Clin Radiol. 2011;66:597-604. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 44] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Cornelia L, Stephan B, Michel B, Antoine W, Felix K. Trans-perineal versus endo-anal ultrasound in the detection of anal sphincter tears. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2002;103:79-82. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 38] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Roche B, Deléaval J, Fransioli A, Marti MC. Comparison of transanal and external perineal ultrasonography. Eur Radiol. 2001;11:1165-1170. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 52. | Oom DM, West RL, Schouten WR, Steensma AB. Detection of anal sphincter defects in female patients with fecal incontinence: a comparison of 3-dimensional transperineal ultrasound and 2-dimensional endoanal ultrasound. Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55:646-652. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 57] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Weinstein MM, Pretorius DH, Jung SA, Nager CW, Mittal RK. Transperineal three-dimensional ultrasound imaging for detection of anatomic defects in the anal sphincter complex muscles. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:205-211. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 63] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Kołodziejczak M, Santoro GA, Słapa RZ, Szopiński T, Sudoł-Szopińska I. Usefulness of 3D transperineal ultrasound in severe stenosis of the anal canal: preliminary experience in four cases. Tech Coloproctol. 2014;18:495-501. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Sultan AH, Loder PB, Bartram CI, Kamm MA, Hudson CN. Vaginal endosonography. New approach to image the undisturbed anal sphincter. Dis Colon Rectum. 1994;37:1296-1299. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 77] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Nicholls MJ, Dunham R, O’Herlihy S, Finan PJ, Sagar PM, Burke D. Measurement of the anal cushions by transvaginal ultrasonography. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:1410-1413. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Zbar AP, Murison R. Transperineal ultrasound in the assessment of haemorrhoids and haemorrhoidectomy: a pilot study. Tech Coloproctol. 2010;14:175-179. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Beer-Gabel M, Carter D, Venturero M, Zmora O, Zbar AP. Ultrasonographic assessment of patients referred with chronic anal pain to a tertiary referral centre. Tech Coloproctol. 2010;14:107-112. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |