Peer-review started: January 30, 2014

First decision: March 19, 2014

Revised: November 16, 2014

Accepted: December 3, 2014

Article in press: January 4, 2015

Published online: January 26, 2015

In recent years attention has been raised to the fact of increased morbidity and mortality between women who suffer from coronary disease. The identification of the so called Yentl Syndrome has emerged the deeper investigation of the true incidence of coronary disease in women and its outcomes. In this review an effort has been undertaken to understand the interaction of coronary disease and female gender after the implementation of newer therapeutic interventional and pharmaceutics’ approaches of the modern era.

Core tip: Coronary disease although remains a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in women, is however underestimated mainly because of the protective role of estrogens that results in lower rates of the disease until the age of mid-fifty. In this review detailed information about the prevalence and the consequences of the disease in women are quoted as well as evidence concerning the results of invasive treatment and use of modern drug therapy.

- Citation: Vaina S, Milkas A, Crysohoou C, Stefanadis C. Coronary artery disease in women: From the yentl syndrome to contemporary treatment. World J Cardiol 2015; 7(1): 10-18

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v7/i1/10.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v7.i1.10

Coronary artery disease (CAD) constitutes a form of modern epidemic, as it still remains the leading cause of mortality and morbidity in the ageing western societies[1]. The prevalence of CAD in the general population varies, depending on age and sex. In terms of age, there is a trend of more incidents in older ages. Concerning sex, until the age of 60 years old, the predicted probability of having an acute myocardial infarction (AMI) is by far higher in men than in women (60.6% vs 33.0%, respectively)[1]. Therefore, CAD is widely believed to be a man’s disease, although it accounts for more deaths in women at the age of 35 years than breast cancer (Table 1)[2]. This has been mainly attributed to the protective role of estrogens in the cardiovascular system as they enhance vascular function, reduce the inflammatory response, increase metabolism and insulin sensitivity and finally promote cardiac myocyte and stem cell survival[3]. As a consequence, female hormones may partially account for women’s longevity observed in randomized control trials, where women with CAD are older than men and have more co-morbidities such as diabetes, hypertension and chronic kidney disease[4,5]. At menopause, the lack of the protective effect of estrogens leads to a 10-fold increase in the prevalence of CAD in women compared to a 4.6 fold increase in men of the same age[6]. Finally, by the 7th decade of life the increasing rate of CAD among women results in similar rates of the disease among the two genders, although lifestyle factors seem to have a different impact on clinical outcome between gender[1,7,8].

| Diseases | Remaining lifetime risk at the age of 40 yr | Remaining lifetime risk at the age of 70 yr | ||

| Men | Women | Men | Women | |

| Any CVD | 2 in 31 | 1 in 21 | 2 in 32 | 1 in 2 |

| CHD | 1 in 2 | 1 in 3 | 1 in 3 | 1 in 4 |

| AF | 1 in 4 | 1 in 4 | 1 in 4 | 1 in 4 |

| CHF | 1 in 5 | 1 in 5 | 1 in 5 | 1 in 5 |

| Stroke | 1 in 63 | 1 in 53 | 1 in 6 | 1 in 5 |

| Dementia | … | … | 1 in 7 | 1 in 5 |

| Hip fracture | 1 in 20 | 1 in 6 | … | … |

| Breast cancer | … | 1 in 8 | … | 1 in 15 |

| Prostate cancer | 1 in 6 | … | 1 in 9 | … |

| Lung cancer | 1 in 13 | 1 in 16 | 1 in 15 | 1 in 20 |

| Colon cancer | 1 in 19 | 1 in 21 | 1 in 25 | 1 in 27 |

| DM | 1 in 3 | 1 in 3 | 1 in 9 | 1 in 7 |

| Hypertension | 9 in 103 | 9 in 103 | 9 in 10 | 9 in 10 |

| Obesity | 1 in 3 | 1 in 3 | … | … |

Due to the above mentioned characteristics of the female gender, and the fact that the majority of trials more often enroll younger patients, the representation of women in clinical trials was until recently relatively low, approximately 30% (Table 2)[9,10]. Even in one of the largest contemporary trials designed to compare outcomes between invasive and conservative pharmacological treatment in patients with stable CAD, the COURAGE trial (Clinical Outcomes Utilizing Revascularization and AGgressive Drug Evaluation), men encountered for approximately 85% of the study group[11]. As a result, women suffering from CAD are handled diagnostically and therapeutically based on conclusions drawn mainly from male populations. This observation underscores the need for a more gender focused approach both in every day clinical practice but also in large scale trials. The purpose of the present review is to explore the available data depicting the best strategies to recognise and treat CAD in women.

| Study | Sample MT.PCI | Enrollment n | Mean age (yr) | Male (%) | DM (%) | % Prior MI | 1/2/3-Vessel CAD | % No symptoms | % Mean EF | % Follow up, yr |

| RITA-2 | 514/504 | 1992-1996 | 58 (Median) | 82 | 9 | 47 | 60/33/7 | 20 | ND1 | 7 |

| ACME-1 | 115/112 | 1987-1990 | 60 | 100 | 18 | 31 | 100/0/0 | 9 | 68 | 2.4-52 |

| ACME-2 | 50/51 | 1987-1990 | 60 | 100 | 18 | 41 | 0/100/0 | 18 | 67 | 2.4-52 |

| AVERT | 164/177 | 1995-1996 | 59 | 84 | 16 | 42 | 56/44/0 | 16 | 61 | 1.5 |

| Dakik et al[58] | 22/19 | 1995-1996 | 53 | 59 | ND | 100 | 44/41/15 | 0 | 46 | 1 |

| MASS | 72/72 | 1988-1991 | 56 | 58 | 18 | 0 | 100/0/0 | 0 | 76 | 5 |

| MASS II | 203/205 | 1995-2000 | 60 | 68 | 30 | 41 | 0/42/58 | ND | 67 | 1 |

| ALKK | 151/149 | 1994-1997 | 58 | 87 | 16 | 100 | 100/0/0 | 0 | ND3 | 4.7 |

| Sievers et al[59] | 44/44 | ND | 56 | ND | 0 | 55 | 100/0/0 | ND | ND | 2 |

| Hambrecht et al[60] | 51/50 | 1997-2001 | 61 | 100 | 23 | 46 | 58/27/15 | 0 | 63 | 1 |

| Bech et al[61] | 91/90 | ND | 61 | 64 | 12 | 25 | 66/28/6 | 0 | 65 | 2 |

It has been demonstrated that women tend to present for chest pain evaluation in the emergency room at a greater rate compared to men (4.0 million visits for women vs 2.4 million visits for men). However, women tend to present with less typical symptoms, such as fatigue (70.7%), sleep disturbance (47.8%) and shortness of breath (42.1%)[12], back pain, indigestion, weakness, nausea/vomiting, dyspnoea and weakness[13,14]. At an older age, with more co-morbidities including diabetes, peripheral vascular disease, chronic kidney disease and hypertension[15]. A great amount of literature explored this phenomenon giving rise to large scale clinical trials which resulted in the identification of three paradoxes with regard to female sex and CAD manifestation[13]. (1) Women have disproportionately lower burden of atherosclerosis and obstructive CAD compared with the extent of angina they complain for; (2) Compared to men, women have less severe CAD despite the fact that they are older with a greater risk factor burden; and (3) Even though CAD is less evident in women, as illustrated by invasive diagnostic imaging modalities, females still have a more adverse prognosis compared to men.

Another parameter of great importance is the incr-easing prevalence of the cardiac X syndrome or coronary microvascular dysfunction among women of post-menopausal age. It is evident that almost 40% of the operated coronary angiographies reveal non obstructive atherosclerosis although patients present with anginal symptoms and positive exercise training results[16]. A large proportion out of 30% of these findings is attributed to coronary microvascular dysfunction as no other identifiable cause can be found. The most interesting aspect of this group of patients is the fact that it is consisted in its great proportion (almost 70%) of post-menopausal women[17]. In contrast to the findings of earlier studies that microvascular angina does not affect long term prognosis[18], it is evident nowadays from a large retrospective analysis of 11223 patients referred for coronary angiography with stable angina, that patients with non-obstructive CAD consolidate a further increase in the risk of coronary events and of all-cause mortality (HR = 1.85; 95%CI: 1.51-2.28; and 1.52; 95%CI: 1.24-1.88, respectively)[19].

Thus, women are frequently a clinical challenge for the cardiologist and their symptom misinterpretation may lead to the wrong diagnosis and treatment with potentially unfavourable consequences. Symptom evaluation and recognition in women is a matter of great importance, since it has been shown that when typical symptoms accompany an acute coronary syndrome (ACS) there is no difference in the disease diagnosis between women and men[20]. Moreover, when prodromal symptoms are recognised in women before an ACS, women have better survival in comparison to men[21].

Not only diagnostic evaluation of women may be misleading, but also the appropriate treatment selection can be difficult. It was already recognized in 1991 that women suffering from CAD had less chances to be introduced either in coronary angiography or percutaneous coronary intervention (15.4% of women vs 27.3% of men, P < 0.001)[22]. This approach was demonstrated even in cases were admission symptoms were more prominent in women than in men[23]. Unlike men, women were submitted less frequently to any diagnostic or therapeutic intervention creating in this way dissimilarity on curing procedures. This alarming fact was described by Bernadine Healy, the first woman director of National Health Institute in United States, as the Yentl syndrome named after the Jewish heroine of Isaac Singer, who was masqueraded as a boy in order to be educated in the Talmud philosophy. Healy concluded that when a woman has been shown to have extensive CAD, like men, only then she gets the appropriate treatment[24]. Since, a plethora of studies examined gender differences in order to provide the best treatment options for women.

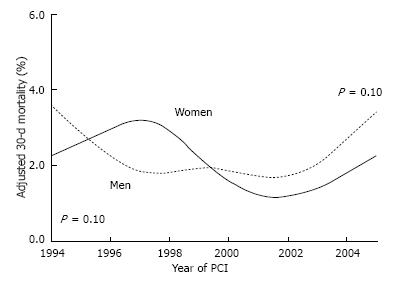

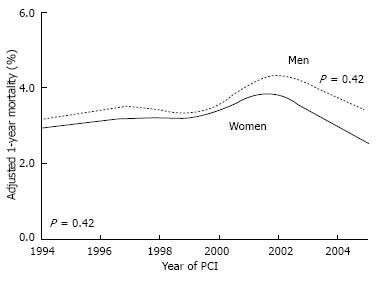

One of the first studies comparing the impact of percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI) with bare metal stent (BMS) implantation between females and males, revealed that women had 50% more chance of death in comparison to men after adjustment for age, co-morbidities, and extend of coronary atherosclerosis[25]. However, in the same analysis, after final adjustment for Body Surface Area, mortality rates were similar between the two genders, although a slighter increased rate of stroke, vascular complications and repeat in-hospital revascularization was observed in women[25]. Similar results were reported in a retrospective analysis from Mayo Clinic investigating 18885 consecutive, patients who underwent PCI between 1979 and 1995 (early group) and between 1996 and 2004 (late group)[26]. The results indicated no difference in terms of 30-d mortality, while after adjustment for baseline risk factors, again there was no difference observed in short or long term mortality between the two genders (Figures 1 and 2)[26]. The study indicated that between the two groups a decrease in 30 d mortality was observed in both genders during the 25-year follow up period.

A retrospective study from Rotterdam investigated the outcomes of Sirolimus Eluting Stents, Pacliataxel Eluting Stents and BMS in women[27]. In this study, even though women had worse baseline characteristics compared to men, no differences in 3-year outcomes were detected between males and females.

A recent meta-analysis, which included 43904 patients (26.3% women) in 26 trials, assessed the safety and efficacy of DES in women[28]. The study showed that DES implantation in women was more effective and safe than BMS implantation. Furthermore, it was observed that 2nd and 3rd generation DES, such as everolimus-eluting Xience and Promus stents, zotarolimus-eluting Endeavor and Resolute stents, biolimus-eluting Biomatrix and Nobori stents, and sirolimus-eluting Yukon stents, were associated with an improved safety profile compared with early-generation DES[28]. These results suggest that women undergoing PCI may benefit more when DES and moreover newer generation DES are used.

An interesting meta-analysis was designed in order to evaluate whether female gender is an independent risk factor for repeated coronary revascularization after PCI. The results indicated that although female sex increases the short term rate of repeated revascularization after PCI the long term rate was the same between the two genders clarifying the fact that even for this parameter female gender is not an independent risk factor[29].

Bleeding complications at the point of vascular pun-cture, hematomas and retroperitoneal bleedings are decreased in the current era. This is mainly due to introduction of less aggressive anticoagulant regimens, adjustment of heparin dose according to body mass index and smaller size catheters. However, women still continue to be at 1.5 to 4 times greater risk for bleeding in comparison to men (Table 3)[30]. Reduced Body Surface Area, altered pharmacokinetics and diminished drug metabolism are the main aspects of female gender that attribute mostly in these higher bleeding rates.

| Study | n | Vascular complications | ||

| Women | Men | P-value | ||

| Alfonso | 981 | 11/157 (7.0%) | 16/824 (2.0%) | < 0.01 |

| Antoniucci | 1019 | 14/234 (6.0) | 24/785 (3.0%) | 0.01 |

| BOAT | 989 | 6/237 (2.5%) | 6/752 (0.8%) | 0.05 |

| CAVEAT | 512 | 14/128 (10.8%) | 22/384 (5.8%) | 0.003 |

| NACI | 2855 | 39/971 (4.0%) | 28/1884 (1.5%) | < 0.05 |

| NCN | 109708 | 1955/36204 (5.4%) | 1985/73504 (2.7%) | < 0.001 |

| NHLBI | 2136 | 24/555 (4.4%) | 36/1581(2.3%) | < 0.05 |

| NHLBI | 2524 | 44/883 (5.0%) | 43/1641(2.6%) | < 0.01 |

| STARS | 1965 | 44/570 (7.8%) | 39/1395 (2.8%) | < 0.01 |

| Trabatoni | 1100 | 15/165 (9.3%) | 33/935 (3.5%) | 0.004 |

| Welty | 5989 | 34/2096 (1.6%) | 23/3893 (0.6%) | < 0.001 |

| WHC | 7372 | 78/2064 (3.8%) | 125/5308 (2.4%) | < 0.001 |

| Combined | 137150 | 2278/44264 (5.1%) | 2380/92886 (2.6%) | |

Newer anticoagulant agents were recently introduced in clinical practice raising expectations for further bleeding risk reduction. In order to evaluate this hypothesis, novel studies were contacted to evaluate the action of direct thrombin inhibitor bivalirudin (ANGIOX®) in both genders who suffered from moderate and high-risk ACS[31]. Out of 7789 patients submitted to PCI, 2561 received heparin and IIb-IIIa glycoprotein inhibitor, 2609 received bivalirudin in combination to IIb-IIIa glycoprotein inhibitor and 2619 received bivalirudin solely. The group of patient to receive bivalirudin in comparison to the group of patient receiving heparin in combination to IIb-IIIa glycoprotein inhibitor displayed the same degree of ischemic events but with a lesser degree of major bleeding (4% vs 7%, P < 0.0001)[31]. Interestingly, bivalirudin alone decreased the variance of bleeding between the two genders, but it did not completely eliminate it.

In order to achieve decreased bleeding rates in women, the idea of radial approach during intervention was implemented into clinical practice. However, due to women’s smaller vessel size and lower pain threshold it was revealed that 14% of women were finally switched to femoral approach in contrast to 1.7% of men[32]. In the same study however, during 299 radial interventions in women no major bleeding was observed, whereas in 601 femoral intervention, 25 major bleedings where recorded (P = 0.0008). In addition, radial approach was related with a lower rate of minor bleeding (6.4% vs 39.4% P = 0.00001). These favourable results indicate that radial approach during PCI in women is safer in terms of bleeding, even though there are more difficulties to initiate the procedure through the particular access site.

In the past, women submitted to CABG were shown to have higher perioperative morbidity and mortality compared to men[33-35]. These first results raised the issue of CABG safety in women and initiated the conduction of several newer trials. Indeed, over 20 trials investigated the impact of CABG in women compared to men. A recent meta-analysis confirmed that women experience higher mortality rates in comparison to men in terms of short-, mid- and long-term follow-up with the higher mortality recorded in the short-term period[36]. Several explanations for this observation have been proposed such as the delayed reference of women to CABG when CAD extends to a greater degree, the smaller size of women coronary vessels that creates technical issues to the surgeon or finally the limited use of left internal mammary artery in women[37-39].

Arterial Revascularization Therapies Study Part I (ARTS I) was one of the first studies to compare CABG and PCI in women. The study demonstrated that for a total of 1205 patients there was no significant difference in terms of death, stroke, or myocardial infarction between the two genders. However, stenting was ascossiated to a greater need for repeated revascularization[40,41].

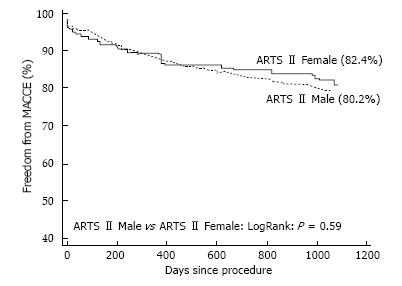

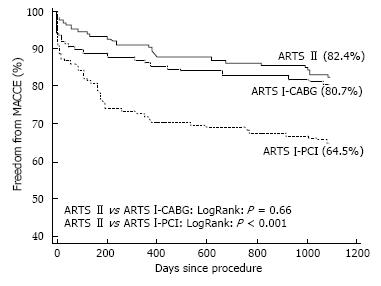

Newer studies in the Drug Eluting Stent (DES) era sought to further investigate the effect of gender on PCI and CABG outcomes. The multicenter randomized study Arterial Revascularization Therapies Study-Part II (ARTS II) was designed to evaluate the outcomes of Sirolimus Eluting Stent implantation in comparison to BMS implantation and Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting (CABG) in patients with multivessel CAD[41]. In ARTS II, although women tended to have more risk factors compared to men, they experienced the same rate of adverse events with men at 30 d, one year and three years after Sirolimus Eluting Stent implantation (Figure 3)[37]. Additionally, it was observed that both genders had a more favorable clinical outcome with Sirolimus Eluting Stents compared with BMS but similar to CABG (Figure 4)[41].

These results could potentially institute PCI as the first choice treatment in women with multivessel disease.

The vast majority of women, about 60%, experience an acute coronary syndrome (ACS) or sudden cardiac death as the first manifestation of the disease[42]. The initial results comparing gender differences in patients with ACS were presented in the pre-thrombolytic era, where a 28% mortality rate was demonstrated in women compared to a 16% mortality among men[43]. Women also experienced a 3 fold higher rate of reinfarction. In the following years, the introduction of thrombolysis decreased the total mortality rates in the general population. However, a discrepancy was still evident between the two genders (30 d unadjusted mortality rate was 13.1% in women and 4.8% in men)[44]. Newer, large scale studies were undertaken in order to re-evaluate these results in the modern era of invasive approach to ACS. One of the largest trials investigating these aspects enrolled 78254 patients (39% women) with AMI in 420 United States hospitals from 2001 to 2006[45]. The results reconfirmed the data observed in previous trials. The study showed that women with ACS are older, with more comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome and tend to present less often with ST-elevation AMI[46-48]. Adjusted analysis revealed no differences in terms of mortality between the two genders for ACS, but in the subgroup of ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction (STEMI) there was a statistically significant and almost double proportion of mortality in women (10.2% women vs 5.5% men, P < 0.0001). An important conclusion from this trial was the fact that women received less often aspirin and b-blockers and were less often treated in an invasive manner with percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty.

This approach was also noticed in an earlier contacted study in Minnesota (46% less chances of invasive approach) as well as in a in a Swiss national registry where the rate of women introduced in PCI was significantly lower than men (OR = 0.70; 95%CI: 0.64 to 0.76)[15,48].

These observations raised the question of whether physicians prefer more conservative strategies because women have higher mortality rates with invasive pro-cedures or whether women are less willing to undergo such a procedure. PRimary Angioplasty in patients transferred from General community hospitals to specialized PTCA Units with or without Emergency thrombolysis 1 and 2 studies evaluated 520 patients with STEMI treated with thrombolytics and 530 patients treated with primary PCI. Women treated with thrombolytics had almost two fold higher mortality than women treated with primary PCI (P = 0.043)[49]. Therefore, although patient demographic data were not adjusted to body mass index, which could have an effect on the unadjusted doses of streptokinase used, it can be concluded that primary PCI to treat women with AMI is superior to a more conservative approach. Similar results were demonstrated in the Global Utilization of Streptokinase and TPA for Occluded Coronary Arteries II-B and in a sub-analysis of the Primary Angioplasty in Myocardial Infarction trial comparing newer thrombolytic agents vs PCI[50,51]. More recent studies showed that mortality and major adverse cardiac events, though higher among women with primary PCI in unadjusted analyses, are comparable in both genders after adjusting for age, hypertension, smoking, diabetes mellitus, stent diameter, and time between symptoms onset and ambulance arr-ival[52-55]. A meta-analysis that included 8 trials and almost 10115 patients, demonstrated that low-risk women with ACS may benefit from a more conservative approach. However, males and high-risk females with ACS treated with an invasive strategy have similar clinical outcome in terms of death, MI, or rehospitalisation for ACS[56].

It has been consistently shown that women who are suffering from CAD usually present with less typical symptoms, at an older ager and with more co-morbidities compared with men. Therefore, they constitute a high risk group that potentially poses a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. However, it seems that in the modern era, where sophisticated interventional and surgical techniques have emerged, women significantly benefit from an early invasive approach provided an intense medical monitoring is implemented.

P- Reviewer: Fraccaro C, Rathore S S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Sytkowski PA, D’Agostino RB, Belanger A, Kannel WB. Sex and time trends in cardiovascular disease incidence and mortality: the Framingham Heart Study, 1950-1989. Am J Epidemiol. 1996;143:338-350. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Mosca L, Appel LJ, Benjamin EJ, Berra K, Chandra-Strobos N, Fabumni RP, Grady D, Haan CK, Hayes SN, Judelson DR. Summary of the American Heart Association’s evidence-based guidelines for cardiovascular disease prevention in women. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:394-396. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 47] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Murphy E. Estrogen signaling and cardiovascular disease. Circ Res. 2011;109:687-696. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 266] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 310] [Article Influence: 23.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Clayton TC, Pocock SJ, Henderson RA, Poole-Wilson PA, Shaw TR, Knight R, Fox KA. Do men benefit more than women from an interventional strategy in patients with unstable angina or non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction? The impact of gender in the RITA 3 trial. Eur Heart J. 2004;25:1641-1650. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 116] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lagerqvist B, Säfström K, Ståhle E, Wallentin L, Swahn E. Is early invasive treatment of unstable coronary artery disease equally effective for both women and men? FRISC II Study Group Investigators. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38:41-48. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Duvall WL. Cardiovascular disease in women. Mt Sinai J Med. 2003;70:293-305. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Shaw LJ, Bairey Merz CN, Pepine CJ, Reis SE, Bittner V, Kelsey SF, Olson M, Johnson BD, Mankad S, Sharaf BL. Insights from the NHLBI-Sponsored Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE) Study: Part I: gender differences in traditional and novel risk factors, symptom evaluation, and gender-optimized diagnostic strategies. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:S4-S20. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 505] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 487] [Article Influence: 27.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Aggelopoulos PCC, Pitsavos C, Panagiotakos DB, Vaina S, Brili S, Lazaros G, Vavouranakis M, Stefanadis C: Gender differences on the impact of physical activity to left ventricular systolic function in elderly patients with an acute coronary event. Hellenic J Cardiol. 2014;In press. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | Katritsis DG, Ioannidis JP. Percutaneous coronary intervention versus conservative therapy in nonacute coronary artery disease: a meta-analysis. Circulation. 2005;111:2906-2912. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 295] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 307] [Article Influence: 16.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Tsang W, Alter DA, Wijeysundera HC, Zhang T, Ko DT. The impact of cardiovascular disease prevalence on women‘s enrollment in landmark randomized cardiovascular trials: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:93-98. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 40] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Boden WE, O’Rourke RA, Teo KK, Hartigan PM, Maron DJ, Kostuk WJ, Knudtson M, Dada M, Casperson P, Harris CL. Optimal medical therapy with or without PCI for stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1503-1516. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 3259] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 3059] [Article Influence: 179.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | McSweeney JC, Cody M, O’Sullivan P, Elberson K, Moser DK, Garvin BJ. Women’s early warning symptoms of acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2003;108:2619-2623. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 288] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 268] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Bairey Merz CN, Shaw LJ, Reis SE, Bittner V, Kelsey SF, Olson M, Johnson BD, Pepine CJ, Mankad S, Sharaf BL. Insights from the NHLBI-Sponsored Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE) Study: Part II: gender differences in presentation, diagnosis, and outcome with regard to gender-based pathophysiology of atherosclerosis and macrovascular and microvascular coronary disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:S21-S29. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 556] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 563] [Article Influence: 31.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | DeVon HA, Ryan CJ, Ochs AL, Shapiro M. Symptoms across the continuum of acute coronary syndromes: differences between women and men. Am J Crit Care. 2008;17:14-24; quiz 25. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 15. | Nguyen JT, Berger AK, Duval S, Luepker RV. Gender disparity in cardiac procedures and medication use for acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2008;155:862-868. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 79] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Patel MR, Peterson ED, Dai D, Brennan JM, Redberg RF, Anderson HV, Brindis RG, Douglas PS. Low diagnostic yield of elective coronary angiography. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:886-895. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1067] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1116] [Article Influence: 79.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kaski JC, Rosano GM, Collins P, Nihoyannopoulos P, Maseri A, Poole-Wilson PA. Cardiac syndrome X: clinical characteristics and left ventricular function. Long-term follow-up study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;25:807-814. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 333] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 298] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Lichtlen PR, Bargheer K, Wenzlaff P. Long-term prognosis of patients with anginalike chest pain and normal coronary angiographic findings. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;25:1013-1018. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 19. | Jespersen L, Hvelplund A, Abildstrøm SZ, Pedersen F, Galatius S, Madsen JK, Jørgensen E, Kelbæk H, Prescott E. Stable angina pectoris with no obstructive coronary artery disease is associated with increased risks of major adverse cardiovascular events. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:734-744. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 511] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 582] [Article Influence: 44.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Milner KA, Funk M, Arnold A, Vaccarino V. Typical symptoms are predictive of acute coronary syndromes in women. Am Heart J. 2002;143:283-288. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 21. | Graham MM, Westerhout CM, Kaul P, Norris CM, Armstrong PW. Sex differences in patients seeking medical attention for prodromal symptoms before an acute coronary event. Am Heart J. 2008;156:1210-1216.e1. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 39] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Ayanian JZ, Epstein AM. Differences in the use of procedures between women and men hospitalized for coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:221-225. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 811] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 764] [Article Influence: 23.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Steingart RM, Packer M, Hamm P, Coglianese ME, Gersh B, Geltman EM, Sollano J, Katz S, Moyé L, Basta LL. Sex differences in the management of coronary artery disease. Survival and Ventricular Enlargement Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:226-230. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 623] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 593] [Article Influence: 18.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Healy B. The Yentl syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:274-276. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 327] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 300] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Peterson ED, Lansky AJ, Kramer J, Anstrom K, Lanzilotta MJ. Effect of gender on the outcomes of contemporary percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol. 2001;88:359-364. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 26. | Singh M, Rihal CS, Gersh BJ, Roger VL, Bell MR, Lennon RJ, Lerman A, Holmes DR. Mortality differences between men and women after percutaneous coronary interventions. A 25-year, single-center experience. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:2313-2320. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Onuma Y, Kukreja N, Daemen J, Garcia-Garcia HM, Gonzalo N, Cheng JM, van Twisk PH, van Domburg R, Serruys PW. Impact of sex on 3-year outcome after percutaneous coronary intervention using bare-metal and drug-eluting stents in previously untreated coronary artery disease: insights from the RESEARCH (Rapamycin-Eluting Stent Evaluated at Rotterdam Cardiology Hospital) and T-SEARCH (Taxus-Stent Evaluated at Rotterdam Cardiology Hospital) Registries. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2009;2:603-610. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 40] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Stefanini GG, Baber U, Windecker S, Morice MC, Sartori S, Leon MB, Stone GW, Serruys PW, Wijns W, Weisz G. Safety and efficacy of drug-eluting stents in women: a patient-level pooled analysis of randomised trials. Lancet. 2013;382:1879-1888. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 81] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Chen Z, Qian J, Ma J, Ge L, Ge J. Effect of gender on repeated coronary artery revascularization after intra-coronary stenting: a meta-analysis. Int J Cardiol. 2012;157:381-385. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Lansky AJ, Hochman JS, Ward PA, Mintz GS, Fabunmi R, Berger PB, New G, Grines CL, Pietras CG, Kern MJ. Percutaneous coronary intervention and adjunctive pharmacotherapy in women: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2005;111:940-953. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 181] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 191] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Stone GW, White HD, Ohman EM, Bertrand ME, Lincoff AM, McLaurin BT, Cox DA, Pocock SJ, Ware JH, Feit F. Bivalirudin in patients with acute coronary syndromes undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: a subgroup analysis from the Acute Catheterization and Urgent Intervention Triage strategy (ACUITY) trial. Lancet. 2007;369:907-919. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 310] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 245] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Pristipino C, Pelliccia F, Granatelli A, Pasceri V, Roncella A, Speciale G, Hassan T, Richichi G. Comparison of access-related bleeding complications in women versus men undergoing percutaneous coronary catheterization using the radial versus femoral artery. Am J Cardiol. 2007;99:1216-1221. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 84] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | O’Connor GT, Morton JR, Diehl MJ, Olmstead EM, Coffin LH, Levy DG, Maloney CT, Plume SK, Nugent W, Malenka DJ. Differences between men and women in hospital mortality associated with coronary artery bypass graft surgery. The Northern New England Cardiovascular Disease Study Group. Circulation. 1993;88:2104-2110. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 34. | Brandrup-Wognsen G, Berggren H, Hartford M, Hjalmarson A, Karlsson T, Herlitz J. Female sex is associated with increased mortality and morbidity early, but not late, after coronary artery bypass grafting. Eur Heart J. 1996;17:1426-1431. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 35. | Edwards FH, Carey JS, Grover FL, Bero JW, Hartz RS. Impact of gender on coronary bypass operative mortality. Ann Thorac Surg. 1998;66:125-131. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 36. | Alam M, Bandeali SJ, Kayani WT, Ahmad W, Shahzad SA, Jneid H, Birnbaum Y, Kleiman NS, Coselli JS, Ballantyne CM. Comparison by meta-analysis of mortality after isolated coronary artery bypass grafting in women versus men. Am J Cardiol. 2013;112:309-317. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 69] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | O’Connor NJ, Morton JR, Birkmeyer JD, Olmstead EM, O’Connor GT. Effect of coronary artery diameter in patients undergoing coronary bypass surgery. Northern New England Cardiovascular Disease Study Group. Circulation. 1996;93:652-655. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 38. | Aldea GS, Gaudiani JM, Shapira OM, Jacobs AK, Weinberg J, Cupples AL, Lazar HL, Shemin RJ. Effect of gender on postoperative outcomes and hospital stays after coronary artery bypass grafting. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999;67:1097-1103. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 39. | Sharoni E, Kogan A, Medalion B, Stamler A, Snir E, Porat E. Is gender an independent risk factor for coronary bypass grafting? Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;57:204-208. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 15] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Serruys PW, Unger F, Sousa JE, Jatene A, Bonnier HJ, Schönberger JP, Buller N, Bonser R, van den Brand MJ, van Herwerden LA. Comparison of coronary-artery bypass surgery and stenting for the treatment of multivessel disease. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1117-1124. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 808] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 850] [Article Influence: 37.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Vaina S, Voudris V, Morice MC, De Bruyne B, Colombo A, Macaya C, Richardt G, Fajadet J, Hamm C, Schuijer M. Effect of gender differences on early and mid-term clinical outcome after percutaneous or surgical coronary revascularisation in patients with multivessel coronary artery disease: insights from ARTS I and ARTS II. EuroIntervention. 2009;4:492-501. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 42. | Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Borden WB, Bravata DM, Dai S, Ford ES, Fox CS. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2013 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013;127:e6-e245. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2921] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 3335] [Article Influence: 303.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Kannel WB, Sorlie P, McNamara PM. Prognosis after initial myocardial infarction: the Framingham study. Am J Cardiol. 1979;44:53-59. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 44. | Woodfield SL, Lundergan CF, Reiner JS, Thompson MA, Rohrbeck SC, Deychak Y, Smith JO, Burton JR, McCarthy WF, Califf RM. Gender and acute myocardial infarction: is there a different response to thrombolysis? J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;29:35-42. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 45. | Jneid H, Fonarow GC, Cannon CP, Hernandez AF, Palacios IF, Maree AO, Wells Q, Bozkurt B, Labresh KA, Liang L. Sex differences in medical care and early death after acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2008;118:2803-2810. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 377] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 394] [Article Influence: 24.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Hasdai D, Porter A, Rosengren A, Behar S, Boyko V, Battler A. Effect of gender on outcomes of acute coronary syndromes. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:1466-1469, A6. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 47. | Alfredsson J, Stenestrand U, Wallentin L, Swahn E. Gender differences in management and outcome in non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome. Heart. 2007;93:1357-1362. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 121] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Radovanovic D, Erne P, Urban P, Bertel O, Rickli H, Gaspoz JM. Gender differences in management and outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndromes: results on 20,290 patients from the AMIS Plus Registry. Heart. 2007;93:1369-1375. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 181] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 199] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Motovska Z, Widimsky P, Aschermann M. The impact of gender on outcomes of patients with ST elevation myocardial infarction transported for percutaneous coronary intervention: analysis of the PRAGUE-1 and 2 studies. Heart. 2008;94:e5. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 28] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Tamis-Holland JE, Palazzo A, Stebbins AL, Slater JN, Boland J, Ellis SG, Hochman JS. Benefits of direct angioplasty for women and men with acute myocardial infarction: results of the Global Use of Strategies to Open Occluded Arteries in Acute Coronary Syndromes Angioplasty (GUSTO II-B) Angioplasty Substudy. Am Heart J. 2004;147:133-139. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 51. | Stone GW, Grines CL, Browne KF, Marco J, Rothbaum D, O’Keefe J, Hartzler GO, Overlie P, Donohue B, Chelliah N. Comparison of in-hospital outcome in men versus women treated by either thrombolytic therapy or primary coronary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 1995;75:987-992. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 52. | Suessenbacher A, Doerler J, Alber H, Aichinger J, Altenberger J, Benzer W, Christ G, Globits S, Huber K, Karnik R. Gender-related outcome following percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-elevation myocardial infarction: data from the Austrian acute PCI registry. EuroIntervention. 2008;4:271-276. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 53. | Wijnbergen I, Tijssen J, van ‘t Veer M, Michels R, Pijls NH. Gender differences in long-term outcome after primary percutaneous intervention for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;82:379-384. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 50] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Valente S, Lazzeri C, Chiostri M, Giglioli C, Zucchini M, Grossi F, Gensini GF. Gender-related difference in ST-elevation myocardial infarction treated with primary angioplasty: a single-centre 6-year registry. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2012;19:233-240. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 37] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Benamer H, Tafflet M, Bataille S, Escolano S, Livarek B, Fourchard V, Caussin C, Teiger E, Garot P, Lambert Y. Female gender is an independent predictor of in-hospital mortality after STEMI in the era of primary PCI: insights from the greater Paris area PCI Registry. EuroIntervention. 2011;6:1073-1079. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 94] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | O’Donoghue M, Boden WE, Braunwald E, Cannon CP, Clayton TC, de Winter RJ, Fox KA, Lagerqvist B, McCullough PA, Murphy SA. Early invasive vs conservative treatment strategies in women and men with unstable angina and non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008;300:71-80. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 329] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 340] [Article Influence: 21.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Blaha MJ, Dai S, Ford ES, Fox CS, Franco S. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2014 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014;129:e28-e292. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 3046] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 3492] [Article Influence: 349.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Dakik HA, Kleiman NS, Farmer JA, He ZX, Wendt JA, Pratt CM, Verani MS, Mahmarian JJ. Intensive medical therapy versus coronary angioplasty for suppression of myocardial ischemia in survivors of acute myocardial infarction: a prospective, randomized pilot study. Circulation. 1998;98:2017-2023. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 59. | Sievers N, Hamm CW, Herzner A, Kuck KH. Medical therapy versus PTCA: a prospective, randomized trial in patients with asymptomatic coronary single-vessel disease. Circulation. 1993;88:I-297 Abstract. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 60. | Hambrecht R, Walther C, Möbius-Winkler S, Gielen S, Linke A, Conradi K, Erbs S, Kluge R, Kendziorra K, Sabri O. Percutaneous coronary angioplasty compared with exercise training in patients with stable coronary artery disease: a randomized trial. Circulation. 2004;109:1371-1378. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 61. | Bech GJ, De Bruyne B, Pijls NH, de Muinck ED, Hoorntje JC, Escaned J, Stella PR, Boersma E, Bartunek J, Koolen JJ. Fractional flow reserve to determine the appropriateness of angioplasty in moderate coronary stenosis: a randomized trial. Circulation. 2001;103:2928-2934. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |