Published online May 27, 2012. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v4.i5.114

Revised: March 26, 2012

Accepted: April 10, 2012

Published online: May 27, 2012

AIM: To analyze risk factors for postoperative pancreatic fistula (POPF) rate after distal pancreatic resection (DPR).

METHODS: We performed a retrospective analysis of 126 DPRs during 16 years. The primary endpoint was clinically relevant pancreatic fistula.

RESULTS: Over the years, there was an increasing rate of operations in patients with a high-risk pancreas and a significant change in operative techniques. POPF was the most prominent factor for perioperative morbidity. Significant risk factors for pancreatic fistula were high body mass index (BMI) [odds ratio (OR) = 1.2 (CI: 1.1-1.3), P = 0.001], high-risk pancreatic pathology [OR = 3.0 (CI: 1.3-7.0), P = 0.011] and direct closure of the pancreas by hand suture [OR = 2.9 (CI: 1.2-6.7), P = 0.014]. Of these, BMI and hand suture closure were independent risk factors in multivariate analysis. While hand suture closure was a risk factor in the low-risk pancreas subgroup, high BMI further increased the fistula rate for a high-risk pancreas.

CONCLUSION: We propose a risk-adapted and indication-adapted choice of the closure method for the pancreatic remnant to reduce pancreatic fistula rate.

- Citation: Wellner UF, Makowiec F, Sick O, Hopt UT, Keck T. Arguments for an individualized closure of the pancreatic remnant after distal pancreatic resection. World J Gastrointest Surg 2012; 4(5): 114-120

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v4/i5/114.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v4.i5.114

Distal pancreatic resection (DPR) is a standard operation for pathological processes of the pancreas located to the left of the mesentericoportal axis. It can be performed with a lower risk of serious complications than pancreatic head resection. The procedure for oncological indications usually includes a splenectomy but can also be extended to major multivisceral resections, including other organs like the adrenal gland, stomach, bowel or kidney. The main cause of morbidity is the development of postoperative pancreatic fistula (POPF), which prolongs hospital stay and can also lead to severe secondary complications. Therefore, various techniques have been described for secure dissection and closure of the pancreatic cut surface, comprising direct closure by hand suture, stapling, electrocautery and ultrasound devices, suture reinforcement with seromuscular patches and sealants, as well as anastomosis to the jejunum. However, so far no single method has been convincingly shown to be superior to others. Some patient-derived risk factors for the development of pancreatic fistula after DPR have been identified[1-22]; most of them, however, cannot be influenced by the surgeon. The aim of this study was to analyze the impact of surgical technique and patient-side risk factors on pancreatic fistula rate and other measures of perioperative outcome after DPR.

All patients in this study were operated in an open procedure via transverse laparotomy. The following techniques were used for closure of the pancreatic remnant: wedge-shaped incision of the cut surface, ligation of the main pancreatic duct and hand suture of the capsule (later on referred to as hand suture closure), transsection and closure with a stapling device (later on referred to as stapler closure), Roux-Y-pancreatojejunostomy (later on referred to as pancreatojejunostomy) without duct-to-mucosa anastomosis and covering of the cut surface with a seromuscular omega-loop jejunal patch after main pancreatic duct ligation (later on referred to as seromuscular patch). Occasionally, a fibrin sealant (TachoSil, Nycomed Pharma GmBH, Germany) was used for suture reinforcement. Before closure of the abdomen, peritoneal drains were placed in the vicinity of the pancreatic stump or anastomosis. All patients were transferred to the intermediate or intensive care unit for surveillance for at least 1 d. Drain amylase levels were routinely measured every day for at least 3 d postoperatively and the drains were removed on day 5 when clinically appropriate. Octreotide was administered routinely if drain amylase activity was elevated (1000 U/L). Abdominal computed tomography (CT) was performed on the basis of clinical course. Suspicious intraabdominal collections were preferably treated by CT-guided interventional drainage and amylase activity was measured in every drain fluid.

On the basis of a prospectively maintained database at our institution, retrospective risk factor analysis was performed. The primary endpoint was pancreatic fistula of grade B or C, as defined by the International Study Group for Pancreatic Surgery[23]. Secondary endpoints included surgical morbidity and overall mortality. Tests for statistical significance were performed with the SPSS 17.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) with a significance level of P < 0.05. Two-sided Mann-Whitney test, two-sided Fisher’s exact test, Spearman rank correlation and binary logistic regression were used for comparison of rational variables, dichotomous variables, bivariate correlation analysis and uni- and multivariate risk factor analysis, respectively.

Patient characteristics and histopathological findings are shown in Table 1. From February 1994 to July 2009 at our institution, 863 patients received a pancreatic resection of whom 126 patients (77 women and 49 men) received a DPR. Patient age varied between 24 and 83 years (median 61 years), with a body mass index (BMI) ranging from 16 to 41 years (median 24 years). One-fifth of patients reported alcohol abuse (mainly patients with chronic pancreatitis) and about the same percentage was diabetic, with the need of oral antidiabetic medication or insulin substitution. Chronic pancreatitis (32%) and pancreatic adenocarcinoma (29%) were the most frequent histopathological findings and about one-third showed cystic neoplasms of the pancreas or neuroendocrine tumors. In detail, cystic neoplasms were usually serous cystic adenomas (11) or mucinous cystic neoplasms (6), while intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (2) and solid pseudopapillary neoplasms (2) rarely occurred in the pancreatic tail.

| Parameter | No POPF (n = 96) | POPF (n = 30) | Odds ratio | P uni-variate | P multi-variate | |

| Patients | ||||||

| Age (yr) | 61 (24-83) | 61 (24-82) | 61 (24-83) | 1.002 | 0.859 | |

| Sex (M:F) | 49:77 | 38:58 | 11:19 | 0.884 | 0.775 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24 (16-41) | 24 (16-34) | 27 (17-41) | 1.181 | 0.001 | 0.009 |

| Diabetes | 24 (19.0) | 20 | 4 | 0.585 | 0.365 | |

| Alcohol | 23 (18.3) | 19 | 4 | 0.623 | 0.427 | |

| Crea (mg/dL) | 0.80 (0.40-1.87) | 0.80 (0.40-1.87) | 0.80 (0.46-1.40) | 0.806 | 0.827 | |

| WBC (tsd/μL) | 6.9 (2.6-18.5) | 6.9 (2.6-18.5) | 6.8 (3.2-17.7) | 0.978 | 0.759 | |

| Hb (g/dL) | 13.2 (7.8-16.8) | 13.1 (7.8-16.8) | 13.4 (10.7-16.6) | 1.189 | 0.174 | |

| Bili (mg/dL) | 0.6 (0.2-1.8) | 0.6 (0.2-1.4) | 0.6 (0.2-1.8) | 0.635 | 0.545 | |

| Operations | ||||||

| Period 94-01 | 43 (34) | 37 | 6 | 2.508 | 0.067 | |

| Period 02-09 | 83 (66) | 59 | 24 | |||

| OP time | 270 (125-570) | 270 (125-570) | 269 (157-510) | 0.996 | 0.154 | |

| DC-HS | 47 (37.3) | 30 | 17 | 2.877 | 0.014 | 0.030 |

| DC-S | 18 (14.3) | 16 | 2 | 0.357 | 0.188 | |

| PJ | 52 (41.3) | 43 | 9 | 0.528 | 0.154 | |

| SMP | 9 (7.1) | 7 | 2 | 0.908 | 0.908 | |

| Splenectomy | 109 (86.5) | 84 | 25 | 0.714 | 0.561 | |

| Multivisceral | 26 (20.6) | 23 | 3 | 0.353 | 0.111 | |

| Histopathology | ||||||

| PDAC | 38 (28.6) | 32 | 4 | 0.308 | 0.042 | |

| CP | 40 (31.7) | 32 | 8 | 0.727 | 0.495 | |

| CNP | 21 (16.7) | 12 | 9 | 3.000 | 0.029 | |

| NET | 16 (12.7) | 12 | 4 | 1.077 | 0.905 | |

| OTH | 13 (10.3) | 8 | 5 | 2.200 | 0.199 | |

| High-risk | 50 (39.5) | 32 | 18 | 3.000 | 0.011 | 0.168 |

Median operation time was 270 min (120-570 min). About 21% of the DPR was part of a multivisceral resection and in less than 15% the spleen was preserved. Three specialized pancreatic surgeons performed over 80% of the operations. The most frequently employed methods for closure of the pancreas were hand suture (hand suture closure 37%) and anastomosis (pancreatojejunostomy 41%) (Table 1).

Univariate analysis disclosed a high BMI [odds ratio (OR) = 1.18 per unit, P = 0.001], pancreas closure by hand suture closure (OR = 2.88, P = 0.014), cystic neoplasm of the pancreas (OR = 3.00, P = 0.029) and more generally a “high-risk pancreas” (OR = 3.00, P = 0.011) as risk factors and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (OR = 0.31, P = 0.042) as a protective factor for pancreatic fistula B/C. In multivariate analysis (binary logistic regression), BMI and direct closure by hand suture were the only independent risk factors (Table 1).

In order to obtain more information about the identified risk factors, we separately analyzed two groups of patients for POPF: high-risk vs low-risk pancreas (Table 2). High-risk pancreas was defined as pathology with OR > 1 for development of pancreatic fistula in univariate analysis (Table 1). Of note, this definition is in concordance with our previous risk factor analysis of pancreatoduodenectomies[24]. As shown in Table 2, only the low-risk group showed a significantly higher pancreatic fistula rate after direct hand suture closure, while in case of a high-risk pancreas, this elevation was not significant. BMI was an additional risk factor for pancreatic fistula in high-risk patients, but had no significant effect in the low-risk group.

| Technique | Low-risk pancreas1 | High-risk pancreas2 | ||||

| POPF | CC | P value | POPF | CC | P value | |

| Hand suture | 8/26 (30.8) | 0.296 | 0.009 | 9/21 (42.9) | 0.122 | 0.400 |

| PJ | 4/36 (11.1) | -0.122 | 0.295 | 5/16 (31.3) | -0.068 | 0.639 |

| Stapler | 0/11 (0) | -0.178 | 0.124 | 2/7 (28.6) | -0.062 | 0.667 |

| SM patch | 0/3 (0) | -0.088 | 0.451 | 2/6 (33.3) | -0.021 | 0.888 |

| Risk factor | ||||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24 (17-30) vs 23 (16-32)3 | 0.178 | 0.125 | 29 (21-41) vs 25 (17-34)3 | 0.349 | 0.013 |

Overall rate of pancreatic fistula of grade B or C was 24%. As shown in Table 3, occurrence of pancreatic fistula B/C correlated significantly with morbidity (overall, surgical and severe morbidity), intraabdominal abscess, reoperation and longer hospital stay (Table 2). Postpancreatectomy hemorrhage and sepsis were more frequent in patients with pancreatic fistula, but constituting a non-significant trend. Overall mortality was below 2% and not significantly associated with pancreatic fistula. Indications for reoperation in the patients with pancreatic fistula were erosion bleeding due to pancreatic fistula (3) and intraabdominal abscess not amenable to sufficient interventional drainage (5). Reoperations in patients without pancreatic fistula were necessary because of anastomotic leakage after multivisceral resection involving the stomach (2), postoperative colonic ischemia (2), postoperative splenic ischemia (1), programmed lavage after DPR for pancreatic abscess (1), bleeding after fenestration of a liver cyst during DPR (1), abdominal abscess in absence of pancreatic fistula (2) and insufficiency of the fascia closure (1). Postoperative mortality occurred due to pulmonary embolism after reoperation for pancreatic fistula with erosion bleeding (1) and shock after colon perforation due to postoperative acute myocardial infarction (1).

| Parameter description for all patients (n = 126) | Groups | Correlation | |||

| Parameter | n (%) | No POPF (n = 96) | POPF (n = 30) | Coefficient | P value |

| POPF | 30 (23.8) | 96 | 30 | 1.000 | NA |

| Overall morbidity | 76 (60.3) | 46 | 30 | 0.453 | < 0.001 |

| Surgical morbidity | 55 (43.7) | 25 | 30 | 0.635 | < 0.001 |

| Severe morbidity | 19 (15.1) | 11 | 8 | 0.181 | 0.043 |

| Inta-abdominal abscess | 17 (13.5) | 5 | 12 | 0.434 | < 0.001 |

| Septic shock | 3 (2.4) | 1 | 2 | 0.157 | 0.079 |

| PPH | 8 (6.3) | 4 | 4 | 0.160 | 0.073 |

| Reoperation | 18 (14.3) | 10 | 8 | 0.198 | 0.026 |

| Overall mortality | 2 (1.6) | 1 | 1 | 0.078 | 0.385 |

| Hospital stay (d), median (range) | 15 (8-143) | 14 (8-143) | 32 (11-108) | 0.552 | < 0.001 |

The number of DPRs performed per year has increased substantially. There were 43 DPR from 1994 to 2001 (n = 43) but 83 from 2002 to 2009 (Table 4). We recognized significant differences when comparing these two time periods. Median patient age increased by over 10 years (51 years vs 64 years, P = 0.001) and the indications changed. The number of DPRs performed for chronic pancreatitis strongly decreased (51% vs 22%, P = 0.001), whereas there was an increase in patients operated on for cystic neoplasms of the pancreas (7% vs 22%, P = 0.044). This translated into a higher number of operations on a “high-risk” pancreas and a tendency for a higher pancreatic fistula rate (14% vs 29%, P = 0.078), as well as a significantly longer overall hospital stay (13 d vs 15 d, P = 0.036). Regarding the operations, there were also significant changes in the preferred method of pancreatic stump closure. Pancreatojejunostomy was performed less frequently while stapler closure and seromuscular patch were only performed in the last 8 years.

| Parameter | 1994-2001 (n = 43) | 2002-2009 (n = 83) | P value |

| Patients | |||

| Age (yr, median) | 51 | 64 | 0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2, median) | 25 | 24 | 0.713 |

| Histology | |||

| PDAC | 8 (19) | 28 (34) | 0.097 |

| CP | 22 (51) | 18 (22) | 0.001 |

| CNP | 3 (7) | 18 (22) | 0.044 |

| NET | 5 (12) | 11 (13) | 1.000 |

| Other | 5 (12) | 8 (10) | 0.762 |

| High-risk pancreas | 13 (30) | 37 (45) | 0.129 |

| Operations | |||

| Multivisceral resections | 9 (21) | 17 (21) | 1.000 |

| Hand suture closure | 13 (30) | 34 (41) | 0.252 |

| Pancreatojejunostomy | 30 (70) | 22 (27) | < 0.001 |

| Stapler closure | 0 (0) | 18 (22) | < 0.001 |

| Seromuscular patch | 0 (0) | 9 (11) | 0.027 |

| Perioperative parameters | |||

| POPF B/C | 6 (14) | 24 (29) | 0.078 |

| OHS (d) | 13 | 15 | 0.036 |

DPR was first performed successfully by Trendelenburg in 1882[25] and has since long become a standard procedure widely performed with very low mortality. However, perioperative morbidity remains substantial from the very first reported cases[25,26] to the most recent large series[1,3-5,16], the most important cause being pancreatic fistula. This is highlighted also by our present study, as we show that most of the perioperative morbidity, including severe complications and reoperations, are strongly associated with pancreatic fistula.

Several large series have identified patient-side risk factors for the development of pancreatic fistula. Among those are male gender[1,2], younger age[3], obesity[2,4-6], soft pancreatic texture[7] and smoking[1], whereas preoperative diabetes has been described as protective against pancreatic fistula[1]. In the present study, we could confirm BMI as the only independent patient-side factor influencing pancreatic fistula rates. It may be argued that a soft “fatty pancreas” is prone to pancreatic fistula development after DPR in the same way as shown for pancreatoduodenectomy by us and others[8,9,24].

Concerning the indications for DPR, trauma to the pancreas was identified by others to constitute a risk factor for pancreatic fistula[1,10,24]. We found that the risk of pancreatic fistula is significantly higher for cystic neoplasm of the pancreas and significantly lower for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. This seems reasonable given that the pancreas is usually fibrotic in pancreatic carcinoma but healthy and soft in cystic neoplasm. In general, we could define a “high-risk pancreas” comprising of several pathologies and confirm it as a risk factor with a 3-fold elevated risk of pancreatic fistula in univariate analysis. Of note, the increased pancreatic fistula rate in the high-risk pancreas group was further exaggerated by a higher BMI.

With respect to the extent of the resection, the following risk factors for pancreatic fistula have been described: extended resection to other organs[11], extended lymphadenectomy[3], extended pancreatic resection of more than 8 cm[5], splenectomy[7], high blood loss[5] and long operation time[12]. Extension to multivisceral resections is relatively common in DPR, with reported rates of 15%-36% in the largest series[2,12,27]. However, only one of these series did identify multivisceral resection as a risk factor for POPF. Our study did not show an influence of operation time, splenectomy or multivisceral resection on pancreatic fistula rates. A possible reason is that extended procedures are usually not performed for the high-risk gland according to our definition, but rather in the setting of pancreatic cancer.

Our study comprised four methods of pancreatic stump closure. The method with the lowest POPF rate was stapler closure, closely followed by PJ and seromuscular patch. As a whole, these techniques performed significantly better than hand suture.

Many investigators have attempted to find the safest method with the lowest pancreatic fistula rate. By far the most frequently performed techniques are direct hand suture or stapler closure. The most recent randomized controlled trial examining the value of those two techniques is the DISPACT trial, which for the primary endpoint of the trail, the development of pancreatic fistula, showed no differences between stapling or suturing the pancreas[13,14]. Several studies found stapled closure to be superior in terms of lower pancreatic fistula rates[10,11,15-17] and both large meta analyses conducted on this topic found a non-significant trend in favor of stapler closure over hand suture closure[18,22]. As far as the technique of the hand suture closure, it has been noted by several authors that ligation of the main pancreatic duct (main pancreatic duct) can reduce pancreatic fistula rates[3,19-21]. Our own data demonstrate hand suture closure as an independent risk factor for pancreatic fistula, even although main pancreatic duct ligation was part of the standard procedure.

Interestingly, the pancreatic fistula rate after hand suture was significantly higher in patients with a low-risk pancreas, while this difference was less pronounced in the high-risk group. A possible explanation may be that in the usually fibrotic low-risk pancreas, flow of pancreatic secretions to the duodenum may be compromised by narrowing of the main pancreatic duct and therefore a drainage procedure like pancreatojejunostomy or a broad-based staple closure can be advantageous over hand suture closure. As we cannot provide sufficient retrospective data on proximal pancreatic duct configuration here, the latter concept still needs to be proven.

The relatively good results of pancreatojejunostomy are also noteworthy: This technique is only rarely performed in other large series but in 43 patients in our series. In other series, a significant reduction of pancreatic fistula compared to main pancreatic duct ligation and simple suture has been reported in analogy[28]. A marked decrease in pancreatic fistula rates by gastric wall covering has been reported in one study from Japan[29]. This is noteworthy given the better results of pancreatogastrostomy vs pancreatojejunostomy after pancreatoduodenectomy[30,31].

As our study comprised a long period of 16 years, we aimed to analyze possible bias and evolutions over time. POPF rates did not change significantly between the first and second study periods, ruling out a strong learning curve bias. On the contrary, we noted an increase in the rate of POPF. We attribute this mainly to changing indications leading to a higher percentage of high-risk glands. Especially cystic neoplasms of the pancreas are more frequently diagnosed and treated operatively. In addition, patient age increased by more than 10 years in median, accompanied by a longer hospital stay, probably due to a longer recovery period after surgery.

There was a significant change in the techniques used for closure of the pancreatic remnant. While hand suture was performed at an equal frequency, PJ has been displaced by stapler closure or seromuscular patch. This reflects the attempt to simplify and improve closure techniques.

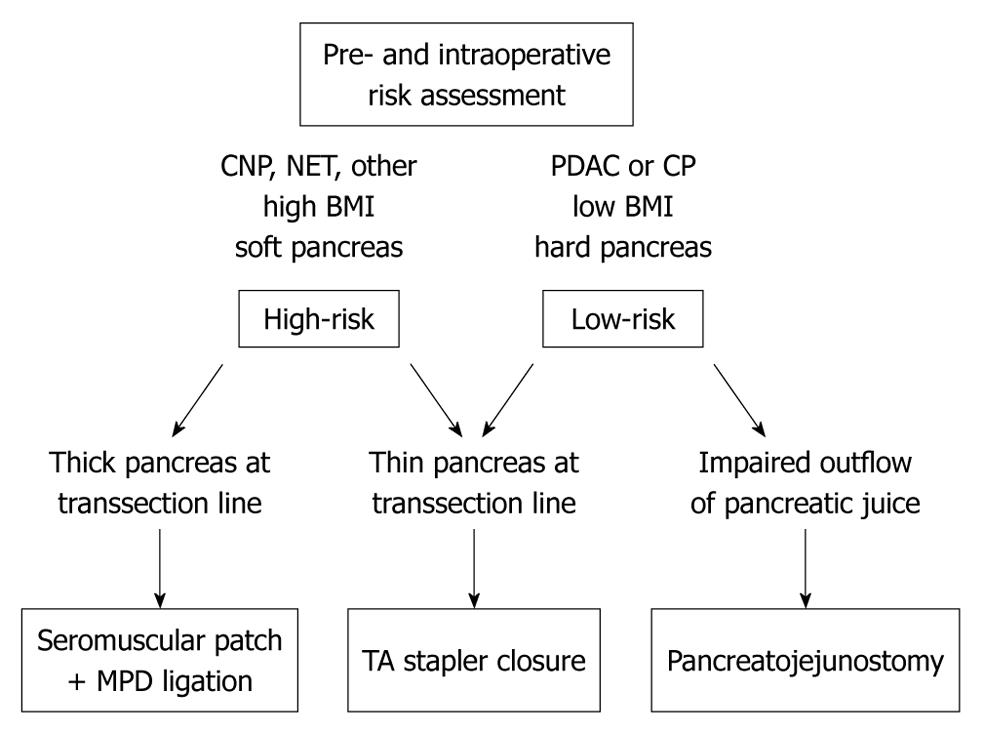

On the basis of our analysis, we propose an individualized approach to DPR (Figure 1) to meet the aforementioned challenges. It is usually possible to assign patients to a high-risk and a low-risk category regarding the risk of pancreatic fistula. This can be done preoperatively and confirmed intraoperatively on the basis of pancreatic texture, as already shown for pancreatic head resection[24].

Stapler closure needs virtually no learning curve, is safe and might therefore be the preferred technique in general. At our institution, the Ethicon Proximate Stapler® is used for stapling the pancreas. The theoretical advantage of the TA closure principle is an equal and slow adaption of the whole suture line at once. We do not use GIA stapling devices (sideways running blade and stapling) because of the risk of insufficient closure of the distal suture when tissue is pushed along the suture line. Importantly in this context, laparoscopic DPR with stapler closure has been shown to significantly reduce hospital stay[32-37] and offers the advantages of minimally invasive surgery and stapler closure. The laparoscopic approach has already been shown to reduce perioperative morbidity in DPR[38].

If stapler closure is not technically feasible, for example due to a very thick pancreas or transsection close to the pancreatic head, closure methods may be chosen depending on risk category: for a healthy and soft pancreas we propose seromuscular patch closure with main pancreatic duct ligation. This might also be done in case of a hard and fibrotic gland. However, in cases of impaired pancreatic juice outflow to the duodenum, as might be the case in chronic pancreatitis, drainage by pancreatojejunostomy may be the procedure of choice.

In summary, while serious morbidity and mortality are low after DPR, changing indications and patient demographics contribute to a constantly high pancreatic fistula rate and pose a challenge to the surgeon. Risk-adapted and indication-adapted use of closure techniques for the pancreatic stump and laparoscopic surgery are options to encounter this problem in the future.

Distal pancreatic resection (DPR) is performed for benign and malignant lesions of the pancreatic tail. Mortality of the procedure is very low. However, postoperative pancreatic fistula (POPF) is the main reason for postoperative morbidity, prolongation of hospital stay and increased health care costs.

The authors present the results DPRs performed at a single center over 16 years, with special regard to POPF, risk factors for POPF and closure techniques for the pancreatic stump.

The authors propose a risk-adapted and indication-adapted choice of the closure method for the pancreatic remnant to reduce pancreatic fistula rate.

By risk- and indication-adapted choice of closure technique, it may be possible to decrease the rates of POPF after DPR.

DPR: removal of the distal part of the pancreas, i.e., to the left of the mesentericoportal axis. In case of malignancy, the spleen is usually included en-bloc. Multivisceral resections extending to neighboring organs (suprarenal gland, stomach, colon or kidney) are possible. POPF: leackage of pancreatic juice from the closed pancreatic stump or pancreatoenteric anastomosis. An international consensus definition has been published by the International Study Group for Pancreatic Surgery.

Based on a great cohort from a single institution the authors analyse their experience with PF following DPRs, with special respect to the influence of the surgical procedure of closure and present some interesting new aspects.

Peer reviewer: Franz Sellner, PhD, Surgical Department, Kaiser-Franz-Josef-Hospital, Engelsburgg 9, Vienna A 1230, Austria

S- Editor Wang JL L- Editor Roemmele A E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | Nathan H, Cameron JL, Goodwin CR, Seth AK, Edil BH, Wolfgang CL, Pawlik TM, Schulick RD, Choti MA. Risk factors for pancreatic leak after distal pancreatectomy. Ann Surg. 2009;250:277-281. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 115] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ferrone CR, Warshaw AL, Rattner DW, Berger D, Zheng H, Rawal B, Rodriguez R, Thayer SP, Fernandez-del Castillo C. Pancreatic fistula rates after 462 distal pancreatectomies: staplers do not decrease fistula rates. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:1691-1697; discussion 1697-1698. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 188] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 195] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Yoshioka R, Saiura A, Koga R, Seki M, Kishi Y, Morimura R, Yamamoto J, Yamaguchi T. Risk factors for clinical pancreatic fistula after distal pancreatectomy: analysis of consecutive 100 patients. World J Surg. 2010;34:121-125. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 80] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Seeliger H, Christians S, Angele MK, Kleespies A, Eichhorn ME, Ischenko I, Boeck S, Heinemann V, Jauch KW, Bruns CJ. Risk factors for surgical complications in distal pancreatectomy. Am J Surg. 2010;200:311-317. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Weber SM, Cho CS, Merchant N, Pinchot S, Rettammel R, Nakeeb A, Bentrem D, Parikh A, Mazo AE, Martin RC. Laparoscopic left pancreatectomy: complication risk score correlates with morbidity and risk for pancreatic fistula. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:2825-2833. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Sledzianowski JF, Duffas JP, Muscari F, Suc B, Fourtanier F. Risk factors for mortality and intra-abdominal morbidity after distal pancreatectomy. Surgery. 2005;137:180-185. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 134] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ridolfini MP, Alfieri S, Gourgiotis S, Di Miceli D, Rotondi F, Quero G, Manghi R, Doglietto GB. Risk factors associated with pancreatic fistula after distal pancreatectomy, which technique of pancreatic stump closure is more beneficial. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:5096-5100. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | Mathur A, Pitt HA, Marine M, Saxena R, Schmidt CM, Howard TJ, Nakeeb A, Zyromski NJ, Lillemoe KD. Fatty pancreas: a factor in postoperative pancreatic fistula. Ann Surg. 2007;246:1058-1064. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | Rosso E, Casnedi S, Pessaux P, Oussoultzoglou E, Panaro F, Mahfud M, Jaeck D, Bachellier P. The role of "fatty pancreas" and of BMI in the occurrence of pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:1845-1851. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Fahy BN, Frey CF, Ho HS, Beckett L, Bold RJ. Morbidity, mortality, and technical factors of distal pancreatectomy. Am J Surg. 2002;183:237-241. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Johnston FM, Cavataio A, Strasberg SM, Hamilton NA, Simon PO, Trinkaus K, Doyle MB, Mathews BD, Porembka MR, Linehan DC. The effect of mesh reinforcement of a stapled transection line on the rate of pancreatic occlusion failure after distal pancreatectomy: review of a single institution's experience. HPB (Oxford). 2009;11:25-31. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 31] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kleeff J, Diener MK, Z'graggen K, Hinz U, Wagner M, Bachmann J, Zehetner J, Müller MW, Friess H, Büchler MW. Distal pancreatectomy: risk factors for surgical failure in 302 consecutive cases. Ann Surg. 2007;245:573-582. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 308] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 322] [Article Influence: 18.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Bruns H, Rahbari NN, Löffler T, Diener MK, Seiler CM, Glanemann M, Butturini G, Schuhmacher C, Rossion I, Büchler MW. Perioperative management in distal pancreatectomy: results of a survey in 23 European participating centres of the DISPACT trial and a review of literature. Trials. 2009;10:58. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 14. | Diener MK, Knaebel HP, Witte ST, Rossion I, Kieser M, Buchler MW, Seiler CM. DISPACT trial: a randomized controlled trial to compare two different surgical techniques of DIStal PAnCreaTectomy - study rationale and design. Clin Trials. 2008;5:534-545. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 15. | Takeuchi K, Tsuzuki Y, Ando T, Sekihara M, Hara T, Kori T, Nakajima H, Kuwano H. Distal pancreatectomy: is staple closure beneficial. ANZ J Surg. 2003;73:922-925. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 16. | Harris LJ, Abdollahi H, Newhook T, Sauter PK, Crawford AG, Chojnacki KA, Rosato EL, Kennedy EP, Yeo CJ, Berger AC. Optimal technical management of stump closure following distal pancreatectomy: a retrospective review of 215 cases. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14:998-1005. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 40] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Zhao YP, Hu Y, Liao Q, Zhang TP, Guo JC, Cong L. [The utility of stapler in distal pancreatectomy]. Zhonghua Waike Zazhi. 2008;46:24-26. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 18. | Knaebel HP, Diener MK, Wente MN, Büchler MW, Seiler CM. Systematic review and meta-analysis of technique for closure of the pancreatic remnant after distal pancreatectomy. Br J Surg. 2005;92:539-546. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 19. | Bilimoria MM, Cormier JN, Mun Y, Lee JE, Evans DB, Pisters PW. Pancreatic leak after left pancreatectomy is reduced following main pancreatic duct ligation. Br J Surg. 2003;90:190-196. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 20. | Pannegeon V, Pessaux P, Sauvanet A, Vullierme MP, Kianmanesh R, Belghiti J. Pancreatic fistula after distal pancreatectomy: predictive risk factors and value of conservative treatment. Arch Surg. 2006;141:1071-106; discussion 1076. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 167] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Goh BK, Tan YM, Chung YF, Cheow PC, Ong HS, Chan WH, Chow PK, Soo KC, Wong WK, Ooi LL. Critical appraisal of 232 consecutive distal pancreatectomies with emphasis on risk factors, outcome, and management of the postoperative pancreatic fistula: a 21-year experience at a single institution. Arch Surg. 2008;143:956-965. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 22. | Zhou W, Lv R, Wang X, Mou Y, Cai X, Herr I. Stapler vs suture closure of pancreatic remnant after distal pancreatectomy: a meta-analysis. Am J Surg. 2010;200:529-536. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 23. | Bassi C, Dervenis C, Butturini G, Fingerhut A, Yeo C, Izbicki J, Neoptolemos J, Sarr M, Traverso W, Buchler M. Postoperative pancreatic fistula: an international study group (ISGPF) definition. Surgery. 2005;138:8-13. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 24. | Wellner UF, Kayser G, Lapshyn H, Sick O, Makowiec F, Höppner J, Hopt UT, Keck T. A simple scoring system based on clinical factors related to pancreatic texture predicts postoperative pancreatic fistula preoperatively. HPB (Oxford). 2010;12:696-702. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 25. | Finney JM. VII. Resection of the Pancreas: Report of a Case. Ann Surg. 1910;51:818-829. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 26. | Mayo WJ. I. The Surgery of the Pancreas: I. Injuries to the Pancreas in the Course of Operations on the Stomach. II. Injuries to the Pancreas in the Course of Operations on the Spleen. III. Resection of Half the Pancreas for Tumor. Ann Surg. 1913;58:145-150. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 27. | Lillemoe KD, Kaushal S, Cameron JL, Sohn TA, Pitt HA, Yeo CJ. Distal pancreatectomy: indications and outcomes in 235 patients. Ann Surg. 1999;229:693-68; discussion 693-68;. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 28. | Wagner M, Gloor B, Ambühl M, Worni M, Lutz JA, Angst E, Candinas D. Roux-en-Y drainage of the pancreatic stump decreases pancreatic fistula after distal pancreatic resection. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:303-308. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 29. | Kuroki T, Tajima Y, Tsuneoka N, Adachi T, Kanematsu T. Gastric wall-covering method prevents pancreatic fistula after distal pancreatectomy. Hepatogastroenterology. 2009;56:877-880. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 30. | Wellner U, Makowiec F, Fischer E, Hopt UT, Keck T. Reduced postoperative pancreatic fistula rate after pancreatogastrostomy versus pancreaticojejunostomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:745-751. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 31. | Fernández-Cruz L, Cosa R, Blanco L, López-Boado MA, Astudillo E. Pancreatogastrostomy with gastric partition after pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy versus conventional pancreatojejunostomy: a prospective randomized study. Ann Surg. 2008;248:930-938. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 32. | Vijan SS, Ahmed KA, Harmsen WS, Que FG, Reid-Lombardo KM, Nagorney DM, Donohue JH, Farnell MB, Kendrick ML. Laparoscopic vs open distal pancreatectomy: a single-institution comparative study. Arch Surg. 2010;145:616-621. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 33. | Kooby DA, Gillespie T, Bentrem D, Nakeeb A, Schmidt MC, Merchant NB, Parikh AA, Martin RC, Scoggins CR, Ahmad S. Left-sided pancreatectomy: a multicenter comparison of laparoscopic and open approaches. Ann Surg. 2008;248:438-446. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 34. | DiNorcia J, Schrope BA, Lee MK, Reavey PL, Rosen SJ, Lee JA, Chabot JA, Allendorf JD. Laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy offers shorter hospital stays with fewer complications. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14:1804-1812. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 35. | Aly MY, Tsutsumi K, Nakamura M, Sato N, Takahata S, Ueda J, Shimizu S, Redwan AA, Tanaka M. Comparative study of laparoscopic and open distal pancreatectomy. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2010;20:435-440. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 36. | Finan KR, Cannon EE, Kim EJ, Wesley MM, Arnoletti PJ, Heslin MJ, Christein JD. Laparoscopic and open distal pancreatectomy: a comparison of outcomes. Am Surg. 2009;75:671-679; discussion 679-680. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 37. | Baker MS, Bentrem DJ, Ujiki MB, Stocker S, Talamonti MS. A prospective single institution comparison of peri-operative outcomes for laparoscopic and open distal pancreatectomy. Surgery. 2009;146:635-643; discussion 643-645. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 38. | Nigri GR, Rosman AS, Petrucciani N, Fancellu A, Pisano M, Zorcolo L, Ramacciato G, Melis M. Metaanalysis of trials comparing minimally invasive and open distal pancreatectomies. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:1642-1651. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |