Published online Nov 15, 2018. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v10.i11.421

Peer-review started: August 7, 2018

First decision: August 31, 2018

Revised: September 7, 2018

Accepted: October 10, 2018

Article in press: October 10, 2018

Published online: November 15, 2018

To directly compare the efficacy and toxicity of standard-dose FOLFIRINOX (sFOLFIRINOX) and modified-dose FOLFIRINOX (mFOLFIRINOX, 75% of standard-dose) for pancreatic cancer.

One hundred and thirty pancreatic cancer patients who received sFOLFIRINOX (n = 88) or mFOLFIRINOX (n = 42) as their first-line chemotherapy from January 2013 to July 2017 were retrospectively reviewed. For efficacy analysis, the objective response rate (ORR), disease control rate (DCR), progression-free survival (PFS), and overall survival (OS) were evaluated and compared using Pearson’s chi-square test, Kaplan-Meier plot and log-rank test. The adverse events (AEs) were evaluated, and severe (≥ grade 3) AEs rates of the two groups were compared for toxicity analysis.

The mFOLFIRINOX group included more female patients (30.7% vs 57.1%; P = 0.004) and older patients [age (median), 57 vs 63.5; P = 0.018] than the sFOLFIRINOX group. In the efficacy analysis, the ORR and DCR were not significantly different between the two groups (ORR: 39.8% vs 35.7%; P = 0.656; DCR: 80.7% vs 83.3%; P = 0.716). The median PFS and OS were also not different between the groups (PFS: 8.7 mo vs 8.1 mo, P = 0.272; OS: 13.9 mo vs 13.7 mo, P = 0.476). In the safety analysis with severe AEs, the rates of neutropenia (83.0% vs 66.7%; P = 0.044), anorexia (48.9% vs 28.6%; P = 0.029) and diarrhea (13.6% vs 0.0%; P = 0.009) were markedly lower in the mFOLFIRINOX group.

mFOLFIRINOX showed comparable efficacy but better safety compared to sFOLFIRINOX. If clinically necessary, initiating FOLFIRINOX with 75% of the standard-dose can alleviate toxicity concerns without compromising efficacy.

Core tip: Although the efficacy of FOLFIRINOX for pancreatic cancer has been well demonstrated, its relatively high toxicity rate is an important concern. We aimed to directly compare the efficacy and toxicity of standard-dose FOLFIRINOX and modified-dose FOLFIRINOX (mFOLFIRINOX, 75% of standard-dose) for pancreatic cancer. One hundred and thirty patients with pancreatic cancer (standard: 88 vs modified: 42) were reviewed retrospectively. Response rates, progression-free survival, and overall survival were not different between both groups. However, severe adverse events such as neutropenia, anorexia and diarrhea were significantly lower in the mFOLFIRINOX group. If clinically necessary, initiating FOLFIRINOX with 75% of the standard-dose can alleviate toxicity concerns without compromising efficacy.

- Citation: Kang H, Jo JH, Lee HS, Chung MJ, Bang S, Park SW, Song SY, Park JY. Comparison of efficacy and safety between standard-dose and modified-dose FOLFIRINOX as a first-line treatment of pancreatic cancer. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2018; 10(11): 421-430

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v10/i11/421.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v10.i11.421

Pancreatic cancer (PC) is the fourth-most common cause of cancer deaths estimated in the United States[1]. It is also reported as the fifth-most common cause of cancer-related deaths in South Korea[2]. Despite the introduction of several novel regimens, the five-year survival rate for all stages of PC remains around ten percent[1,2]. These statistics are based on the fact that < 20% of newly diagnosed PC cases are suitable candidates for surgical resection, while disseminated disease was noted in > 50% of new cases[1].

Ever since the survival benefit of gemcitabine in patients with advanced PC was reported, gemcitabine-based regimens have been primarily used for > twenty years[3-6]. Recently, a non-gemcitabine-based combination regimen comprising folinic acid (FA), 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), irinotecan, and oxaliplatin (FOLFIRINOX) was introduced for metastatic PC (MPC). In the PRODIGE4/ACCORD11 randomized phase III trial, FOLFIRINOX was associated with a significant survival benefit compared to gemcitabine monotherapy as the first-line therapy for patients with MPC[7]. Thereafter, several studies were conducted to determine the role of FOLFIRINOX in locally advanced PC (LAPC) or borderline resectable PC (BRPC), and meta-analysis reports showed promising improvements in median survivals and resection rates[8,9]. Consequently, FOLFIRINOX is recommended as a preferred front-line therapy for MPC in major up-to-date guidelines and on the list of options for BRPC or LAPC, although prospective randomized data are still lacking[10-12].

However, the relatively high toxicity of FOLFIRINOX is still a concern. In the PRODIGE4/ACCORD11 trial, FOLFIRINOX showed higher severe toxicity rates than gemcitabine, particularly for grade three or four neutropenia in 45.7% of patients[7]. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines for PC restrict FOLFIRINOX to patients with Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG-PS) 0 or 1[12]. Owing to the high toxicity profile of FOLFIRINOX, several retrospective studies and phase II trials using modified-dose FOLFIRINOX (mFOLFIRINOX) were performed with variable modification strategies. This research showed improved safety profiles and comparable efficacy[13-17]. Nevertheless, clinical feasibility or optimal strategy for dose-modification of FOLFIRINOX still remains unclear, since previous studies on mFOLFIRINOX indirectly compared their results to those of the PRODIGE4/ACCORD11 trial. Direct comparative study between standard-dose FOLFIRINOX (sFOLFIRINOX) and mFOLFIRINOX is still lacking. Therefore, in this study, we directly compared the therapeutic efficacy and safety of sFOLFIRINOX and mFOLFIRINOX as first-line chemotherapies for PC.

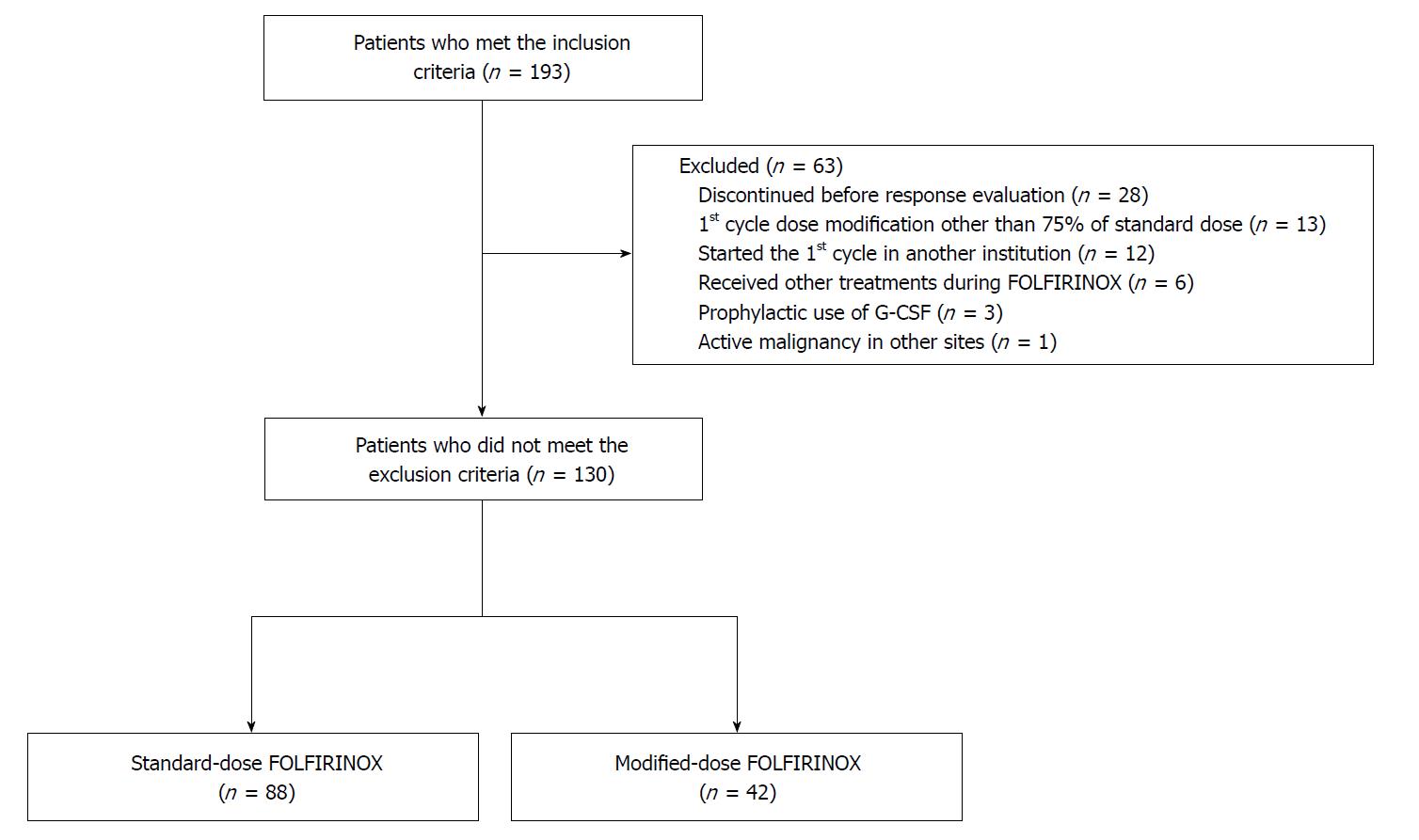

All patients diagnosed with PC who received FOLFIRINOX as their first-line chemotherapy in Severance Hospital from January 2013 to July 2017 were retrospectively reviewed. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) patients over 19 years of age; (2) histologically- or cytologically-proven pancreatic adenocarcinoma; and (3) at least one measurable lesion in accordance with the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST), version 1.1[18]. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) discontinued FOLFIRINOX for any reason before the first response evaluation; (2) dose adjustment in the first cycle other than 75% of the standard-dose; (3) did not start the first cycle of FOLFIRINOX in Severance Hospital; (4) diagnosed other active malignancy at the same time as PC diagnosis; (5) administered another agent in combination with FOLFIRINOX; and (6) regularly administered granulocyte colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) for primary prophylaxis. All patients who met the inclusion criteria and did not meet the exclusion criteria were identified. These patients were divided into sFOLFIRINOX and mFOLFIRINOX groups according to their starting dose of FOLFIRINOX.

Pretreatment assessment was conducted for all patients. Appropriate imaging modalities were used for staging work-up, as needed. The specimen for histological or cytological confirmation of malignancy was obtained by endoscopic ultrasonography-guided fine needle aspiration, percutaneous biopsy, or exploratory laparotomy, as indicated. For each patient, the attending physician made a clinical decision on whether the first cycle should be initiated with sFOLFIRINOX or mFOLFIRINOX. sFOLFIRINOX comprised a 2 h intravenous infusion (IVF) of oxaliplatin 85 mg/m2, followed by a 90 min IVF of irinotecan 180 mg/m2. FA 400 mg/m2 IVF was performed over 2 h after termination of irinotecan infusion. This was followed by a 5-FU 400 mg/m2 bolus and 2400 mg/m2 IVF for 46 h. Patients who received a standard dose at the first cycle were grouped as sFOLFIRINOX. Patients who started with a 75% of standard-dose based on the decision of the attending physician were grouped as mFOLFIRINOX. All patients were regularly administered 0.25 mg of palonosetron 30 min before oxaliplatin infusion for emesis prophylaxis. G-CSF was not used for primary prophylaxis of neutropenia, and was administered when grade three or four neutropenia or neutropenic fever occurred. FOLFIRINOX was repeated every 2 wk until evidence of progressive disease (PD), significant deterioration of patient condition, or patient unwillingness. Dose reduction or delay was at the treating physician’s discretion and fully considered if the patient did not appear to tolerate the dosage of the previous cycle.

Primary endpoints of this study were objective response rate (ORR) and disease control rate (DCR). Secondary endpoints were progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS). Treatment response was evaluated after every four cycles using computed tomography or magnetic resonance image. All imaging modalities were conducted and reviewed in compliance with the institutional standard protocols. According to the RECIST, responses were reported by a professional radiologist, and the final assessment was independently made by each attending physician. The best treatment response of each patient was recorded. The ORR included the rate of complete response (CR) and partial response (PR), while DCR was defined as a sum of ORR and the rate of stable disease (SD). For survival analysis, the patient’s survival status, date of death, and date of last follow-up were recorded. The cut-off date of both survival and follow-up data was February 6, 2018. PFS was defined from the date of initiation of FOLFIRINOX to PD or death. The patients who survived and remained without PD were censored at the date of the last follow-up. Patients who missed a follow-up without PD and with < a 6-mo follow-up period were censored at 6 mo from treatment initiation, even if deaths were confirmed after that. If a treatment switch occurred without PD, such as curative resection, irreversible electroporation, or another chemotherapeutic regimen, the date of switching treatment was considered as the censoring point. OS was always defined from the date of initiation of FOLFIRINOX to death. Patients whose deaths were not confirmed were censored at the date of the last follow-up.

Treatment-related AE was also included in the secondary endpoints of this study. During the period of chemotherapy, treatment-related adverse events (AEs) were monitored and recorded by the attending physicians at each visit. All of the patients’ medical records on AEs were reviewed. The assessment of AEs was carried out in conformity with the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 4.03[19]. AEs leading to dose-reduction or dose-delay were recorded separately.

For comparing the variables of both groups, Mann-Whitney test was used for continuous variables and Pearson’s χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test were used for categorical variables. For the analysis of survival data, the Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate the median survival with a 95% confidence interval (CI) and the log-rank test was used for comparison. A Cox proportional-hazards model was used to estimate the adjusted hazard ratios (HR). P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed with IBM SPSS (version 23.0, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States).

In total, 130 patients were included in the final analysis based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Of the 130 patients, 88 were assigned to the sFOLFIRINOX group and 42 patients were assigned to the mFOLFIRINOX group. The detailed flow chart of patient selection is shown in Figure 1. When comparing the pretreatment characteristics, the mFOLFIRINOX group included more female patients (30.7% vs 57.1%; P = 0.004) and older patients [age (median), 57 vs 63.5; P = 0.018] than the sFOLFIRINOX group (Table 1). Other characteristics did not differ between the two groups.

| sFOLFIRINOX | mFOLFIRINOX | P value | |

| (n = 88) | (n = 42) | ||

| Sex, n (%) | 0.0041 | ||

| Male | 61 (69.3) | 18 (42.9) | |

| Female | 27 (30.7) | 24 (57.1) | |

| Age, yr | 0.0181 | ||

| Median (range) | 57 (31-79) | 63.5 (41-77) | |

| ECOG-PS, n (%) | 0.426 | ||

| 0 | 68 (77.3) | 35 (83.3) | |

| 1 | 20 (22.7) | 7 (16.7) | |

| Laboratory test results, median (range) | |||

| Absolute neutrophil count, /μL | 4200 (1610-11170) | 4525 (2080-18930) | 0.317 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 12.3 (7.1-17.1) | 12.1 (8.5-14.9) | 0.36 |

| Platelet count, × 103/μL | 218 (76-439) | 245 (107-764) | 0.247 |

| Total bilirubin, mg/dL | 0.7 (0.2-4.8) | 0.5 (0.2-2.7) | 0.144 |

| Albumin, g/dL | 3.9 (2.8-5.0) | 3.9 (2.4-4.8) | 0.797 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 0.67 (0.37-1.02) | 0.70 (0.37-1.04) | 0.516 |

| Level of CA 19-9 | |||

| U/mL, median (range) | 172.2 (0.6-20000.0) | 455.5 (0.7-20000.0) | 0.709 |

| Normal, n (%) | 17 (19.3) | 11 (21.5) | 0.274 |

| Elevated, < 59 × ULN, n (%) | 53 (60.2) | 19 (45.2) | |

| Elevated, ≥ 59 × ULN, n (%) | 18 (20.5) | 12 (28.6) | |

| Biliary drainage, n (%) | 0.435 | ||

| Presence | 29 (33.0) | 11 (26.2) | |

| Tumor location in pancreas, n (%) | 0.657 | ||

| Head | 40 (45.5) | 16 (38.1) | |

| Body and tail | 44 (50.0) | 23 (54.8) | |

| Recurrent | 4 (4.5) | 3 (7.1) | |

| Tumor size, cm | 0.313 | ||

| Median (range) | 3.6 (1.3-7.7) | 4.0 (1.3-8.0) | |

| Disease extent, n (%) | 0.243 | ||

| Borderline resectable | 17 (19.3) | 6 (14.3) | |

| Locally advanced | 26 (29.5) | 8 (19.0) | |

| Metastatic | 45 (51.1) | 28 (66.7) | |

| Stage, n (%) | 0.248 | ||

| II | 24 (27.3) | 8 (19.0) | |

| III | 19 (21.6) | 6 (14.3) | |

| IV | 45 (51.1) | 28 (66.7) | |

| Prior treatment, n (%) | |||

| Naïve | 75 (85.2) | 33 (85.7) | 0.941 |

| Curative resection | 4 (4.5) | 4 (9.5) | 0.272 |

| CCRT | 9 (10.2) | 4 (9.5) | 1.000 |

The treatment characteristics are summarized in Table 2. The number of cycles administered and treatment duration were not different between the two groups. The median relative dose intensities (RDIs) of each of the four agents were significantly higher in the sFOLFIRINOX group than in the mFOLFIRINOX group. The proportion of patients who experienced dose-reduction after the first cycle was larger in the sFOLFIRINOX group than in the mFOLFIRINOX group (70.5% vs 38.1%; P < 0.001); however, the rate of dose delay was not different between the two groups. Dose reduction due to neutropenia was higher in the sFOLFIRINOX group (60.2% vs 21.4%; P < 0.001), and, therefore, more patients were administered G-CSF (81.8% vs 64.3%; P = 0.028) and more G-CSF administrations were performed during the treatment period [3.5 times (range: 0-24) vs 2 times (range: 0-12); P = 0.043] than in the mFOLFIRINOX group.

| sFOLFIRINOX | mFOLFIRINOX | P value | |

| (n = 88) | (n = 42) | ||

| Number of cycles administered, median (range) | 9.5 (4-24) | 12 (4-32) | 0.421 |

| Treatment duration, d, median (range) | 126 (42-322) | 154 (42-434) | 0.595 |

| RDI to sFOLFIRINOX, %, median (range) | |||

| Oxaliplatin | 85.3 (56.3-100) | 75.0 (51.1-75.0) | < 0.0011 |

| Irinotecan | 85.0 (56.3-100) | 75.0 (51.1-75.0) | < 0.0011 |

| 5-FU (bolus) | 92.1 (21.4-100) | 75.0 (51.1-75.0) | < 0.0011 |

| 5-FU (infusion) | 94.1 (56.3-100) | 75.0 (51.1-75.0) | < 0.0011 |

| Patients with ≥ 1 dose reduction, n (%) | 62 (70.5) | 16 (38.1) | < 0.0011 |

| Cause of dose reduction (> 5%), n (%) | |||

| Neutropenia | 53 (60.2) | 9 (21.4) | < 0.0011 |

| Febrile neutropenia | 10 (11.4) | 4 (9.5) | 1.000 |

| Patients with ≥ 1 dose delay, n (%) | 55 (62.5) | 22 (52.4) | 0.272 |

| Cause of dose delay (> 5%), n (%) | |||

| Neutropenia | 16 (18.2) | 5 (11.9) | 0.363 |

| Febrile neutropenia | 16 (18.2) | 5 (11.9) | 0.363 |

| Fatigue | 7 (8.0) | 8 (19.0) | 0.081 |

| No. of G-CSF administered, median (range) | 3.5 (0-24) | 2 (0-12) | 0.0431 |

| Patients received G-CSF, n (%) | 72 (81.8) | 27 (64.3) | 0.0281 |

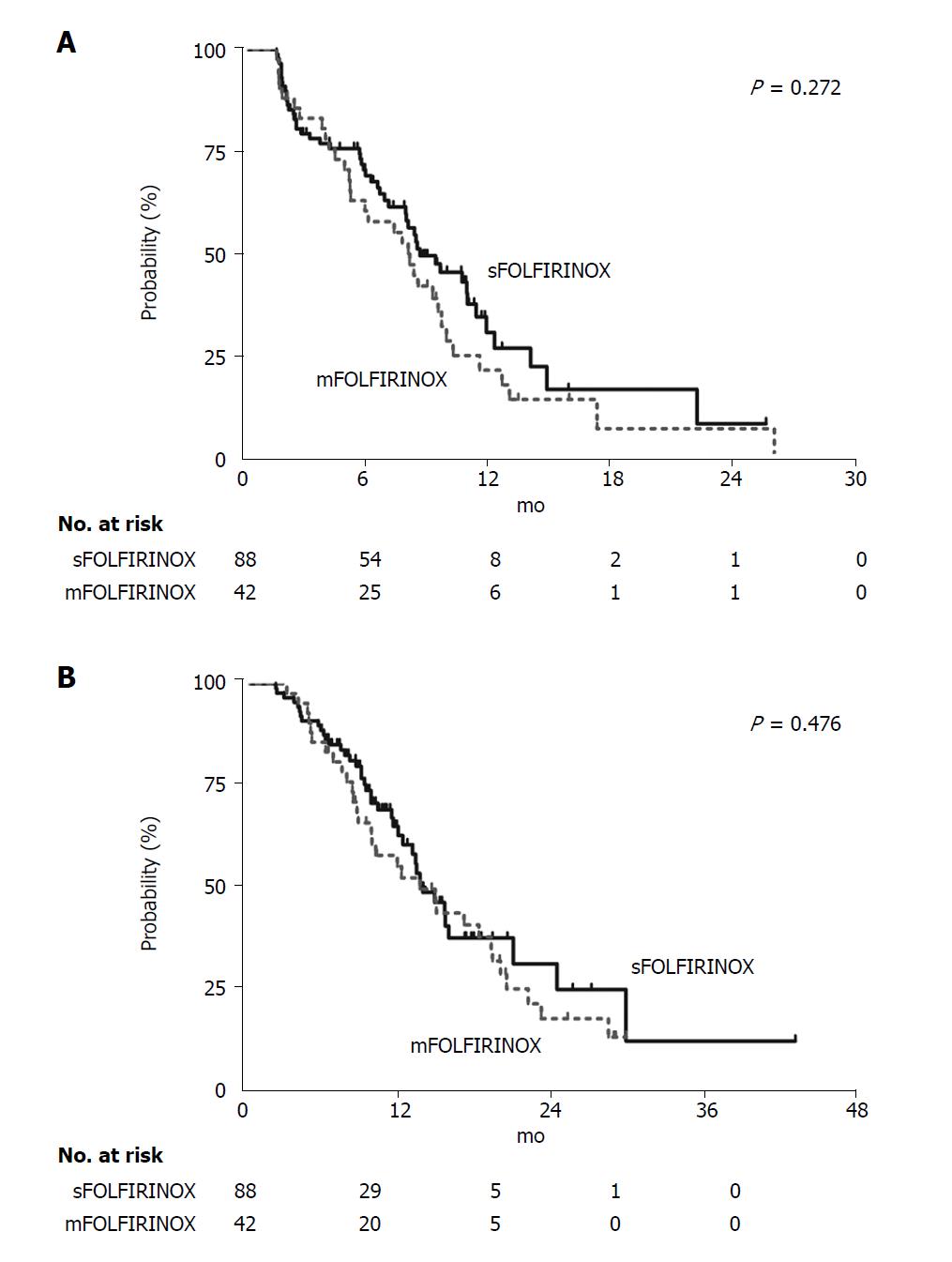

The ORR and DCR (primary end-points of this study) were not different between the two groups (Table 3). The median duration of follow-up was 10.3 mo in the sFOLFIRINOX group and 11.1 mo in the mFOLFIRINOX group (P = 0.181). The estimated median PFS of both groups were not different [sFOLFIRINOX: 8.7 mo (95%CI: 6.4-11.0) vs mFOLFIRINOX: 8.1 mo (95%CI: 6.7-9.6), P = 0.272] (Figure 2A). The estimated median OS of the sFOLFIRINOX group was 13.9 mo (95%CI: 11.5-16.4), and it was not different from that of the mFOLFIRINOX group [13.7 mo (95%CI: 9.5-17.9), P = 0.476] (Figure 2B). Additionally, age and sex-adjusted HRs of the mFOLFIRINOX group to the sFOLFIRINOX group were not statistically significant [HR for disease progression or death, 1.36 (95%CI: 0.81-2.26), P = 0.242; HR for death, 0.94 (95%CI: 0.55-1.60), P = 0.813].

Severe (grade three or higher) treatment-related AEs in the two groups are listed and compared in Table 4. Of the hematologic AEs, the rate of severe neutropenia was significantly lower in the mFOLFIRINOX group than in the sFOLFIRINOX group (83.0% vs 66.7%; P = 0.044). Other hematologic AE rates, including febrile neutropenia, were not different. Severe anorexia and diarrhea occurred less frequently in the mFOLFIRINOX group than in the sFOLFIRINOX group (48.9% vs 28.6%; P = 0.029; 13.6% vs 0.0%; P = 0.009; respectively). All other non-hematologic severe AEs tended to occur less frequently in the mFOLFIRINOX group, with the exception of lung infection.

| Event | sFOLFIRINOX | mFOLFIRINOX | P value |

| (n = 88) | (n = 42) | ||

| Hematologic | |||

| Neutropenia | 73 (83.0) | 28 (66.7) | 0.0441 |

| Febrile neutropenia | 24 (27.3) | 9 (21.4) | 0.474 |

| Anemia | 19 (21.6) | 11 (26.2) | 0.561 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 8 (9.1) | 2 (4.8) | 0.499 |

| Non-hematologic | |||

| Fatigue | 33 (37.5) | 14 (33.3) | 0.644 |

| Anorexia | 43 (48.9) | 12 (28.6) | 0.0291 |

| Nausea/Vomiting | 53 (60.2) | 19 (45.2) | 0.108 |

| Diarrhea | 12 (13.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0.0091 |

| Peripheral sensory neuropathy | 12 (13.6) | 2 (4.8) | 0.224 |

| Sepsis | 5 (5.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0.174 |

| Lung infection | 3 (3.4) | 4 (9.5) | 0.212 |

| Biliary tract infection | 6 (6.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0.176 |

In this study, we aimed to retrospectively compare the therapeutic efficacy and safety of sFOLFIRINOX and mFOLFIRINOX as first-line chemotherapies for PC. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first direct comparative study that evaluated the efficacy and safety of sFOLFIRINOX and mFOLFIRINOX within a single institution. We observed that the median cycle and median duration of FOLFIRINOX were not different in both groups. Although the median RDI of all four agents were significantly less in the mFOLFIRINOX group, the therapeutic parameters such as ORR, DCR, OS, and PFS were not different between the two groups. Regarding the treatment-related AE profiles, severe neutropenia, anorexia, and diarrhea were remarkably lower in the mFOLFIRINOX group than in the sFOLFIRINOX group. Therefore, our study supports dose modification from the initiation of treatment without compromising treatment efficacy, particularly in elderly and female patients, who tend to show more concern about treatment-related toxicities.

Currently, FOLFIRINOX is a universally-used first-line treatment for MPC[20,21], and it is also used for second-line or neoadjuvant treatment. Owing to its severe toxicities (grade ≥ 3 neutropeniain 45.7% of patients; grade ≥ 3 fatigue in 23.6% of patients) reported in the PRODIGE4/ACCORD11 trial[7], treatment-related AE is a major concern when using FOLFIRINOX.

To reduce FOLFIRINOX-related toxicities, several groups have conducted studies focused on dose modification of FOLFIRINOX from the first cycle. Most of the FOLFIRINOX dose-modifying studies compared their results with the PRODIGE4/ACCORD11 trial. Retrospective research conducted in the UK using a reduced dose of irinotecan and omitting a 5-FU bolus reported a markedly lower rate of severe neutropenia than that in the historical trial, with similar rates of other severe AEs[15]. In a US phase II trial using reduced doses of irinotecan and 5-FU bolus, the rates of severe neutropenia and vomiting were significantly lower than the rates in the historical trial; however, other severe AEs were similar[17]. The toxicity of mFOLFIRINOX in this study was less severe than sFOLFIRINOX. In addition, compared with that of the historical trial, the rate of severe diarrhea was lower, but the rates of severe neutropenia, febrile neutropenia, anemia, and vomiting were still higher in the mFOLFIRINOX.

Regarding neutropenia, 77.8% of patients experienced severe neutropenia in a Japanese phase II study of sFOLFIRINOX for chemotherapy-naïve MPC, which is similar to our study’s findings[22]. In addition, most studies conducted in Asian countries reported severe neutropenia in > 65% of patients[23-26], which was more frequent than that in reports from western countries (11.0%-45.7%)[7,27-29]. These results suggest that Asians may be prone to severe FOLFIRINOX-related neutropenia, and dose adjustment is an option that should be considered when treating patients belonging to the Asian population. Unlike the present study, prophylactic G-CSF was routinely administered at every cycle in the aforementioned studies focusing on dose modification of FOLFIRINOX[13-17]. This distinction in therapeutic protocols should be considered when interpreting and comparing the rates of severe neutropenia and neutropenic fever associated with mFOLFIRINOX in our study with those of prior research (67.9% vs 0%-12%; 26.4% vs 0%-5.6%; respectively).

Regarding efficacy, previous studies using a modified form of FOLFIRINOX showed 17.2%-46.7% of ORR and 80%-100% of DCR, which were similar to those of the PRODIGE4/ACCORD11 trial[13,15,17]. Our modification of FOLFIRINOX with 75% of the standard-dose was able to markedly reduce toxicity, and the efficacy was comparable with that of sFOLFIRINOX or previous studies, including the PRODIGE4/ACCORD11 trial. This therefore suggests that, in our study population, dose modification to reduce toxicity is possible without compromising treatment efficacy.

There are certain limitations to this study. First, it has a retrospective study design. Although we selected patients based on strict exclusion criteria, the possibility of selection bias and information bias remains. Second, we included patients with BRPC and unresectable PC. When comparing the survival data with other trials, this characteristic of the patient population should be considered. Third, more females and older patients were included in the mFOLFIRINOX group. These differences may be attributed to the clinical characteristics of the patient, based on whether or not the attending physician decides to administer mFOLFIRINOX from the first cycle. These differences may affect the treatment outcome. A previous study reported that female gender could positively predict response to FOLFIRINOX in patients with advanced PC[30]. However, the prognostic significance of gender in PC remains controversial and warrants further evaluation[31]. Despite these limitations, this study is meaningful because it directly compares the two study groups, which underwent similar clinical practice within a single institution.

In conclusion, mFOLFIRINOX showed comparable efficacy to sFOLFIRINOX, with a better toxicity profile. Given the relatively high toxicity of sFOLFIRINOX, initiating FOLFIRINOX treatment, if clinically required, with 75% of the standard-dose can be an appropriate option to reduce toxicity concerns without compromising efficacy.

Although FOLFIRINOX is one of the universally-used chemotherapies for pancreatic cancer, its relatively high rate of adverse events is still a major concern. Several studies suggest that dose-modified FOLFIRINOX (mFOLFIRINOX) can improve safety with comparable efficacy compared to the standard FOLFIRINOX (sFOLFIRINOX). However, clinical feasibility and the optimal strategy of mFOLFIRINOX remains unclear.

Previous studies on mFOLFIRINOX made conclusions based on comparing their results to the results of historical phase III trials of FOLFIRINOX. To date, direct comparative studies between sFOLFIRINOX and mFOLFIRINOX for pancreatic cancer is lacking.

We directly compared the safety and efficacy of sFOLFIRINOX and mFOLFIRINOX in a single study. This could help clarify the clinical applicability of mFOLFIRINOX.

The medical records of 130 pancreatic cancer patients [sFOLFIRINOX (n = 88), mFOLFIRINOX (n = 42)] were retrospectively reviewed. The objective response rate (ORR), disease control rate (DCR), progression-free survival (PFS), and overall survival (OS) were compared for efficacy analysis. Severe (≥ grade three) adverse event (AE) rates of the two groups were compared for toxicity analysis.

Although the median relative dose intensities of each of the drugs were significantly lower in the mFOLFIRINOX group, the response rates and survival were not different between the two groups (ORR: 39.8% vs 35.7%, P = 0.656; DCR: 80.7% vs 83.3%, P = 0.716; PFS: 8.7 mo vs 8.1 mo, P = 0.272; OS: 13.9 mo vs 13.7 mo, P = 0.476). Severe AE rates, including neutropenia (83.0% vs 66.7%; P = 0.044), anorexia (48.9% vs 28.6%; P = 0.029), and diarrhea (13.6% vs 0.0%; P = 0.009), were significantly lower in the mFOLFIRINOX group.

In this direct comparative restrospective study, mFOLFIRINOX showed comparable efficacy to sFOLFIRINOX, with a better toxicity profile. Given the relatively high toxicity of sFOLFIRINOX, initiating FOLFIRINOX treatment, if clinically required, with 75% of the standard-dose could be an appropriate option to reduce toxicity concerns without compromising efficacy.

In the future, prospective comparative studies need to be conducted to determine the optimal dose modification of FOLFIRINOX and who will benefit from this strategy.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Oncology

Country of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Ouaissi M, Raffaniello R, Sawaki A S- Editor: Ma RY L- Editor: Filipodia E- Editor: Tan WW

| 1. | Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67:7-30. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 11065] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 11879] [Article Influence: 1697.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 2. | Jung KW, Won YJ, Oh CM, Kong HJ, Lee DH, Lee KH; Community of Population-Based Regional Cancer Registries. Cancer Statistics in Korea: Incidence, Mortality, Survival, and Prevalence in 2014. Cancer Res Treat. 2017;49:292-305. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 307] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 323] [Article Influence: 46.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Burris HA 3rd, Moore MJ, Andersen J, Green MR, Rothenberg ML, Modiano MR, Cripps MC, Portenoy RK, Storniolo AM, Tarassoff P, Nelson R, Dorr FA, Stephens CD, Von Hoff DD. Improvements in survival and clinical benefit with gemcitabine as first-line therapy for patients with advanced pancreas cancer: a randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:2403-2413. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4270] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 4043] [Article Influence: 149.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Heinemann V, Quietzsch D, Gieseler F, Gonnermann M, Schönekäs H, Rost A, Neuhaus H, Haag C, Clemens M, Heinrich B. Randomized phase III trial of gemcitabine plus cisplatin compared with gemcitabine alone in advanced pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3946-3952. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 464] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 482] [Article Influence: 26.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Moore MJ, Goldstein D, Hamm J, Figer A, Hecht JR, Gallinger S, Au HJ, Murawa P, Walde D, Wolff RA. Erlotinib plus gemcitabine compared with gemcitabine alone in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: a phase III trial of the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1960-1966. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2755] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2667] [Article Influence: 156.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Von Hoff DD, Ervin T, Arena FP, Chiorean EG, Infante J, Moore M, Seay T, Tjulandin SA, Ma WW, Saleh MN. Increased survival in pancreatic cancer with nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1691-1703. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4035] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 4332] [Article Influence: 393.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Conroy T, Desseigne F, Ychou M, Bouché O, Guimbaud R, Bécouarn Y, Adenis A, Raoul JL, Gourgou-Bourgade S, de la Fouchardière C. FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1817-1825. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4838] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 5100] [Article Influence: 392.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Petrelli F, Coinu A, Borgonovo K, Cabiddu M, Ghilardi M, Lonati V, Aitini E, Barni S; Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio dei Carcinomi dell’Apparato Digerente (GISCAD). FOLFIRINOX-based neoadjuvant therapy in borderline resectable or unresectable pancreatic cancer: a meta-analytical review of published studies. Pancreas. 2015;44:515-521. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 133] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Suker M, Beumer BR, Sadot E, Marthey L, Faris JE, Mellon EA, El-Rayes BF, Wang-Gillam A, Lacy J, Hosein PJ. FOLFIRINOX for locally advanced pancreatic cancer: a systematic review and patient-level meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:801-810. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 653] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 613] [Article Influence: 76.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ducreux M, Cuhna AS, Caramella C, Hollebecque A, Burtin P, Goéré D, Seufferlein T, Haustermans K, Van Laethem JL, Conroy T. Cancer of the pancreas: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2015;26 Suppl 5:v56-v68. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 905] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 844] [Article Influence: 93.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Sohal DP, Mangu PB, Khorana AA, Shah MA, Philip PA, O'Reilly EM, Uronis HE, Ramanathan RK, Crane CH, Engebretson A. Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:2784-2796. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 193] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 215] [Article Influence: 26.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Tempero MA, Malafa MP, Al-Hawary M, Asbun H, Bain A, Behrman SW, Benson AB 3rd, Binder E, Cardin DB, Cha C, Chiorean EG, Chung V, Czito B, Dillhoff M, Dotan E, Ferrone CR, Hardacre J, Hawkins WG, Herman J, Ko AH, Komanduri S, Koong A, LoConte N, Lowy AM, Moravek C, Nakakura EK, O'Reilly EM, Obando J, Reddy S, Scaife C, Thayer S, Weekes CD, Wolff RA, Wolpin BM, Burns J, Darlow S. Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma, Version 2.2017, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2017;15:1028-1061. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 556] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 658] [Article Influence: 109.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Mahaseth H, Brutcher E, Kauh J, Hawk N, Kim S, Chen Z, Kooby DA, Maithel SK, Landry J, El-Rayes BF. Modified FOLFIRINOX regimen with improved safety and maintained efficacy in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Pancreas. 2013;42:1311-1315. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 148] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Blazer M, Wu C, Goldberg RM, Phillips G, Schmidt C, Muscarella P, Wuthrick E, Williams TM, Reardon J, Ellison EC. Neoadjuvant modified (m) FOLFIRINOX for locally advanced unresectable (LAPC) and borderline resectable (BRPC) adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:1153-1159. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 197] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 178] [Article Influence: 19.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ghorani E, Wong HH, Hewitt C, Calder J, Corrie P, Basu B. Safety and Efficacy of Modified FOLFIRINOX for Advanced Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma: A UK Single-Centre Experience. Oncology. 2015;89:281-287. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 35] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Nanda RH, El-Rayes B, Maithel SK, Landry J. Neoadjuvant modified FOLFIRINOX and chemoradiation therapy for locally advanced pancreatic cancer improves resectability. J Surg Oncol. 2015;111:1028-1034. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 56] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Stein SM, James ES, Deng Y, Cong X, Kortmansky JS, Li J, Staugaard C, Indukala D, Boustani AM, Patel V. Final analysis of a phase II study of modified FOLFIRINOX in locally advanced and metastatic pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer. 2016;114:737-743. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 129] [Article Influence: 16.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, Dancey J, Arbuck S, Gwyther S, Mooney M. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:228-247. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 15860] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 19007] [Article Influence: 1267.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 19. | National Cancer Institute. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE). v4.03. ed: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute 2010; https://evs.nci.nih.gov/ftp1/CTCAE/CTCAE_4.03/. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 20. | Le N, Vinci A, Schober M, Krug S, Javed MA, Kohlmann T, Sund M, Neesse A, Beyer G. Real-World Clinical Practice of Intensified Chemotherapies for Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer: Results from a Pan-European Questionnaire Study. Digestion. 2016;94:222-229. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 14] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Abrams TA, Meyer G, Meyerhardt JA, Wolpin BM, Schrag D, Fuchs CS. Patterns of Chemotherapy Use in a U.S.-Based Cohort of Patients with Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer. Oncologist. 2017;22:925-933. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 37] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Okusaka T, Ikeda M, Fukutomi A, Ioka T, Furuse J, Ohkawa S, Isayama H, Boku N. Phase II study of FOLFIRINOX for chemotherapy-naïve Japanese patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer. Cancer Sci. 2014;105:1321-1326. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 128] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kobayashi N, Shimamura T, Tokuhisa M, Goto A, Endo I, Ichikawa Y. Effect of FOLFIRINOX as second-line chemotherapy for metastatic pancreatic cancer after gemcitabine-based chemotherapy failure. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:e6769. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 18] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Muranaka T, Kuwatani M, Komatsu Y, Sawada K, Nakatsumi H, Kawamoto Y, Yuki S, Kubota Y, Kubo K, Kawahata S. Comparison of efficacy and toxicity of FOLFIRINOX and gemcitabine with nab-paclitaxel in unresectable pancreatic cancer. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2017;8:566-571. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 54] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Yoo C, Kang J, Kim KP, Lee JL, Ryoo BY, Chang HM, Lee SS, Park DH, Song TJ, Seo DW. Efficacy and safety of neoadjuvant FOLFIRINOX for borderline resectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma: improved efficacy compared with gemcitabine-based regimen. Oncotarget. 2017;8:46337-46347. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 29] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Yoshida K, Iwashita T, Uemura S, Maruta A, Okuno M, Ando N, Iwata K, Kawaguchi J, Mukai T, Shimizu M. A multicenter prospective phase II study of first-line modified FOLFIRINOX for unresectable advanced pancreatic cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8:111346-111355. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 30] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Marthey L, Sa-Cunha A, Blanc JF, Gauthier M, Cueff A, Francois E, Trouilloud I, Malka D, Bachet JB, Coriat R. FOLFIRINOX for locally advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma: results of an AGEO multicenter prospective observational cohort. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:295-301. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 125] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Chllamma MK, Cook N, Dhani NC, Giby K, Dodd A, Wang L, Hedley DW, Moore MJ, Knox JJ. FOLFIRINOX for advanced pancreatic cancer: the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre experience. Br J Cancer. 2016;115:649-654. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 34] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Faris JE, Blaszkowsky LS, McDermott S, Guimaraes AR, Szymonifka J, Huynh MA, Ferrone CR, Wargo JA, Allen JN, Dias LE. FOLFIRINOX in locally advanced pancreatic cancer: the Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center experience. Oncologist. 2013;18:543-548. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 204] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 216] [Article Influence: 19.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Hohla F, Hopfinger G, Romeder F, Rinnerthaler G, Bezan A, Stättner S, Hauser-Kronberger C, Ulmer H, Greil R. Female gender may predict response to FOLFIRINOX in patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer: a single institution retrospective review. Int J Oncol. 2014;44:319-326. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 28] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Lambert A, Jarlier M, Gourgou Bourgade S, Conroy T. Response to FOLFIRINOX by gender in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer: Results from the PRODIGE 4/ ACCORD 11 randomized trial. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0183288. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 10] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |