Published online Oct 16, 2016. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v8.i18.679

Peer-review started: April 27, 2016

First decision: June 12, 2016

Revised: July 13, 2016

Accepted: August 27, 2016

Article in press: August 29, 2016

Published online: October 16, 2016

Meckel’s diverticulum (MD) is estimated to affect 1%-2% of the general population, and it represents a clinically silent finding of a congenital anomaly in up to 85% of the cases. In adults, MD may cause symptoms, such as overt occult lower gastrointestinal bleeding. The diagnostic imaging workup includes computed tomography scan, magnetic resonance imaging enterography, technetium 99m scintigraphy (99mTc) using either labeled red blood cells or pertechnetate (known as the Meckel’s scan) and angiography. The preoperative detection rate of MD in adults is low, and many patients ultimately undergo exploratory laparoscopy. More recently, however, endoscopic identification of MD has been possible with the use of balloon-assisted enteroscopy via direct luminal access, which also provides visualization of the diverticular ostium. The aim of this study was to review the diagnosis by double-balloon enteroscopy of 4 adults with symptomatic MD but who had negative diagnostic imaging workups. These cases indicate that balloon-assisted enteroscopy is a valuable diagnostic method and should be considered in adult patients who have suspected MD and indefinite findings on diagnostic imaging workup, including negative Meckel’s scan.

Core tip: Meckel’s diverticulum (MD) is estimated to affect 1%-2% of the general population and has 4%-6% risk of causing symptoms during a lifetime. In adults, it may cause occult massive bleeding and the preoperative detection rate is low; patients with undiagnosed MD ultimately undergo exploratory laparoscopy. More recently, however, endoscopic identification of MD has been possible with the use of balloon-assisted enteroscopy via direct luminal access, providing visualization of the diverticular ostium. We report here the use of double-balloon enteroscopy for diagnosing 4 adults with symptomatic MD who had negative diagnostic imaging workup.

- Citation: Gomes GF, Bonin EA, Noda RW, Cavazzola LT, Bartholomei TF. Balloon-assisted enteroscopy for suspected Meckel’s diverticulum and indefinite diagnostic imaging workup. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2016; 8(18): 679-683

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v8/i18/679.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v8.i18.679

Meckel’s diverticulum (MD) is a congenital true diverticulum that develops from a patent omphalo-mesenteric duct[1]. It is estimated to affect 1%-2% of the general population and has 4%-6% risk of causing symptoms during a lifetime[2,3]. Surgical resection is not mandatory for cases of MD that are found incidentally. Any MD > 2 cm in length and with palpable abnormal tissue within the diverticulum, however, is associated with a higher lifetime risk for complication for male patients of ages under 50 years[4], and should be considered for resection. Although MD represents a clinically silent finding of a congenital anomaly in up to 85% of cases[4], patients who develop a complication may suffer from the lack of diagnosis and subsequent delayed initiation of appropriate treatment. When symptoms occur, they usually include melena/hematochezia from a bleeding vessel or abdominal pain from intussusception or adhesions. Confirmation of MD relies on identifying a true diverticulum, usually located within 100 cm from the ileocecal valve. Rarely, a source of bleeding, such as an ulcer, can be found inside its lumen.

In adults, any patient presenting with documented bleeding in the lower gastrointestinal tract and negative findings on upper endoscopy and colonoscopy should be suspected of having a symptomatic MD. The routine diagnostic imaging workup includes computed tomography (CT) scan, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) enterography, technetium 99m scintigraphy (99mTc) using either labeled red blood cells or pertechnetate (known as the Meckel’s scan) and angiography. More recently, however, endoscopic identification of MD has been possible with the use of balloon-assisted enteroscopy via direct luminal access, providing visualization of the diverticular ostium[5].

Herein, we report the use of double-balloon enteroscopy (DBE) for diagnosing 4 adults with symptomatic MD who had negative diagnostic imaging workup.

Between January 2007 and December 2015, 114 patients underwent DBE at Nossa Senhora das Graças Hospital (Curitiba, Brazil). For most patients, the indication for DBE was obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. All patients underwent clinical evaluation by the examiner before the procedure. MD was clinically suspected in young patients with episodes of overt rectal bleeding and negative diagnostic imaging workup. MD was found in 4 patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding, including overt rectal bleeding in 3 and with abdominal pain in 1. The patients included 3 males and 1 female, ranging in age from 16-year-old to 45-year-old (mean, 22-year-old).

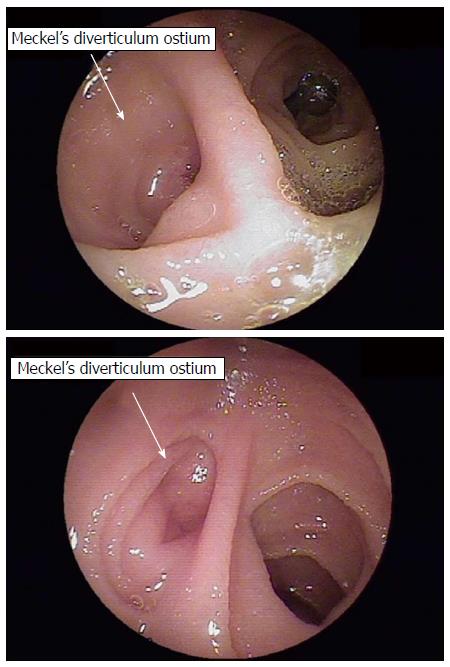

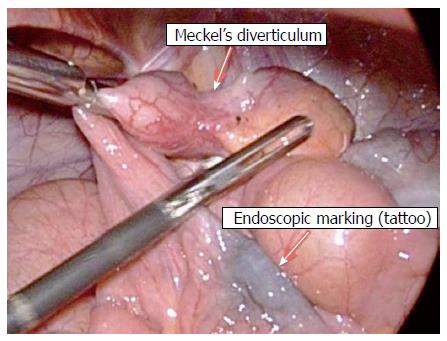

MD diagnosis was made by retrograde (per anus) DBE for all 4 patients, with 1 of the patients having first undergone an unsuccessful approach by anterograde (per mouth). The typical endoscopic feature of MD in these cases was diverticular ostium and lumen in the ileum, found after exhaustive active search (Figure 1). All diverticula were located between 70 cm and 90 cm from the ileocecal valve, and none had stigmata of recent or active bleeding. All patients underwent endoscopic submucosal ink injection (tattooing) of the peridiverticular region, which facilitated a later elective laparoscopic resection (Figure 2).

The equipment used was the Fujinon EN-450P DBE system (Fuji, Tokyo, Japan). All procedures were performed under deep sedation that was established using intravenous propofol.

These two patients had similar symptoms, and as such will be described jointly. Diagnosis occurred at 17-years-old (case 1) and 27-years-old (case 2). Both patients had history of multiple episodes of bleeding with hematochezia, melena and blood transfusion. In both patients, upper and lower endoscopy and red blood cell-labeled scintigraphy gave negative findings. Both patients also had a previous negative Meckel’s scan. Case 2 had experienced an episode of hematochezia with hemodynamic instability, for which an angiography was performed but did not reveal a source of bleeding. Both patients underwent a retrograde DBE, which revealed MD in the ileum.

This 17-year-old male presented to our institution with a history of three episodes of hematochezia, each requiring blood transfusion. He underwent upper endoscopy and colonoscopy, which showed blood clots in the colon but revealed no source of bleeding. A subsequent upper and lower endoscopy, followed by Meckel’s scan and small bowel video capsule exam, provided no additional findings. At admission, hemoglobin and hematocrit were within normal range. Three weeks later, the patient had a new episode of rectal bleeding and was re-hospitalized. A DBE was performed orally until the jejuno-ileal region was reached, which showed normal findings. We then decided to carry out another DBE, this time rectally, and MD was visualized in the ileum at 90 cm from the ileocecal valve. There was no evidence of active bleeding or ulcers around the diverticulum.

This 45-year-old female presented with severe abdominal pain associated with bloating. She had been hospitalized twice within a 2-wk period, and presented clinically with abdominal distension; however, no abdominal mass was palpable. White and red blood cell counts and platelets were normal. An abdominal CT scan was performed and demonstrated thickening of the distal ileum region of about 10 cm in length, which was suspected as obstructive inflammatory bowel disease. A DBE was then performed and showed MD, with no signs of ulceration or obstruction. The patient underwent laparoscopy, which showed MD attached to a mesodiverticular band and determined obstruction of the ileum, located approximately 80 cm from the ileocecal valve.

All patients underwent elective laparoscopic resection of a segment of the small bowel that contained the diverticulum, with end-to-end anastomosis. The treatment was successful in all cases.

MD is considered a true diverticulum, which by definition contains all layers of the intestinal wall. It is located in the ileum, with reported average distances from the ileocecal valve varying according to age: 34 cm in children > 2-year-old; 46 cm in patients between 3-year-old and 21-year-old; 67 cm in adults 21-year or older[6]. MD may have gastric, duodenal, colon, mucosal and pancreatic rests, which originate from multipotent cells within the omphalo-mesenteric duct wall.

A wide array of imaging techniques are available for detecting MD, such as Meckel’s scan, balloon-assisted enteroscopy, capsule endoscopy, CT scan (with or without enterography), MRI enterography and mesenteric catheter angiography. MD diagnosis is more difficult in adults, for whom Meckel’s scan MD’s most accurate diagnostic modality is less accurate, as compared to children[1]. In adults, MD should be suspected in cases of occult gastrointestinal bleeding with no evidence of vascular malformation or of unexplained abdominal pain with an abnormal imaging finding in the ileum. In cases of occult bleeding, the preoperative detection rate is low; adult patients may end up having undiagnosed MD and ultimately undergo exploratory laparoscopy[1].

CT scan is considered the first-line diagnostic method for any adult patient with suspected MD. The sensitivity of CT scan for diagnosing MD has increased over the years, owing to development of the multidetector scan technique (MDCT). This technology provides visualization of the small bowel in various planes, and adding oral contrast (enterography) improves MD imaging[7]. Furthermore, CT is very useful in diagnosing and assessing complications associated with MD, particularly for intra-abdominal abscess formation, obstruction, perforation and associated tumors, which is crucial in acute abdomen cases. MDCT may also detect active extravasation of intravenous contrast medium in cases with active intestinal hemorrhage.

Meckel’s scan is a valuable non-invasive test, in which radioactive tracers are used to locate the presence of functioning ectopic gastric mucosa. In children, it has a sensitivity of 80%-90%, specificity of 95% and accuracy of 90%[2]. In contrast, in adults, the sensitivity is 62.5%, specificity is 9% and accuracy is 46%[8]. According to the guideline recently published by the Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging[8], “the indication for Meckel scintigraphy is to localize ectopic gastric mucosa in a Meckel diverticulum as the source of unexplained gastrointestinal bleeding. Meckel scintigraphy should be used when the patient is not actively bleeding… Even in young children, active bleeding is best studied by radiolabeled red blood cell scintigraphy”. False-positive results are due to the presence of ectopic gastric mucosa elsewhere in the gastrointestinal tract, to enteric duplication and to inflammatory processes. A false-negative result may occur in cases of brisk gastrointestinal bleeding, small gastric ectopic mucosa (< 1.8 cm2) and a “wandering diverticulum”. In our series, all patients had a negative Meckel’s scan. Despite its low accuracy in adults, though, it remains widely used for confirming MD in our geographic region, given its nature of being a non-invasive diagnostic method.

Mesenteric catheter angiography is another diagnostic modality, but it is useful only in cases of ongoing bleeding and for patients with counterindications to a Meckel’s scan. The usual minimum required bleeding rate is of 0.5 mL/min; however, lower bleeding rates can be detected when the digital subtraction angiography technique is applied. This procedure can be useful in locating an overt bleeding vessel and applying embolization treatment; however, it may require super-selective catheterization of the mid- and distal ileal arteries[9].

Diagnosis of small bowel diseases has evolved dramatically over the past decade, particularly since the advent of capsule endoscopy and balloon-assisted enteroscopy. Both procedures enable endoscopic access to the entire small bowel. Capsule endoscopy is a simple, non-invasive technique to examine the small bowel by ingesting a wireless “pill” camera. Although capsule endoscopy has been used for diagnosing MD, its diagnostic yield is limited and there is a risk of capsule retention within the diverticulum[10]. For these reasons, we tend not to use capsule endoscopy for patients with suspected MD.

Balloon-assisted enteroscopy consists of using a single- or a double-balloon method for inserting a flexible endoscope for visualization, biopsy and treatment of the entire small bowel. The first case of MD that was diagnosed by DBE was described in 2005, and since then it has been considered a safe and effective method for diagnosing MD, with a low complication rate in adults[5]. In a recent study by He et al[11], the overall diagnostic yield of DBE for MD before surgery was 86%, which was significantly higher compared to that of capsule endoscopy. Compared to Meckel’s scan, its accuracy is higher for adult patients with suspected symptomatic MD. Admittedly, such results are based upon limited data, but it seems that DBE is becoming a pivotal diagnostic modality for confirming suspected MD in adults. Fukushima et al[5], based on their experience with 10 patients, recommends that dynamic MDCT scan followed by retrograde DBE be applied to stable patients to perform the initial diagnostic workup in adults with suspected MD. In addition, anterograde DBE is recommended as the initial approach for patients with overt, ongoing bleeding, and capsule endoscopy and mesenteric angiography are also suggested for such cases.

DBE offers some advantages over other methods for allowing direct observation of the diverticular ostium, access to the entire small bowel, repeated examinations of the region and intraluminal therapy (i.e. injection, coagulation)[12,13]. Finding another potential source of bleeding may aid in establishing the correct diagnosis, since MD may coexist with several other lesions. Endoscopic tattooing is advised for locating the site of the lesion, whenever an endoscopic revision is needed. In our case series, tattooing also aided in locating the affected segment laparoscopically for subsequent resection. DBE may also reveal unusual MD presentations, such as an inverted MD - a rare condition in which the diverticulum is completely inverted intraluminally and mimics a large subepithelial lesion[12]. Intradiverticular polyps and tumors can be also found through direct visualization inside the MD lumen[5].

Apart from diagnosis, DBE can also provide a minimally invasive endoscopic approach for treatment of symptomatic MD[13,14]. Identifying and treating a bleeding vessel within the MD using DBE[13] can help to avoid an emergency operation. Bleeding control can be accomplished by endoscopic injection, coagulation and clipping. Since rebleeding is a concern, it is advised in such cases to proceed to elective MD resection. Successful cases of intradiverticular MD polypectomy and resection of an inverted MD through DBE have also been reported[14].

In our experience, DBE has emerged over the years as a useful diagnostic modality of adult patients with suspected MD and indefinite findings on diagnostic imaging workup.

The authors describe 4 cases of Meckel’s diverticulum being diagnosed using double-balloon enteroscopy.

Adult patients presenting with overt rectal bleeding or abdominal pain and without diagnosis despite extensive imaging workup.

Gastrointestinal vascular malformations.

Anemia due to bleeding.

Findings from upper endoscopy, lower endoscopy, Meckel’s scan and computed tomography scan were all negative for source of symptoms.

Meckel’s diverticulum.

Complete laparoscopic surgical excision of the diverticulum.

Meckel’s diverticulum may cause occult massive bleeding in adult patients and the preoperative detection rate is low. Endoscopic identification of Meckel’s diverticulum is possible with the use of balloon-assisted enteroscopy via direct luminal access, providing visualization of the diverticular ostium.

Meckel’s diverticulum is the most common congenital anomaly of the gastrointestinal tract. It is estimated to affect 1%-2% of the general population and has 4%-6% risk of causing symptoms during a lifetime. Double-balloon enteroscopy is an endoscopic procedure that allows investigation and treatment of small bowel lesions.

Balloon-assisted enteroscopy is a valuable diagnostic method and should be considered for use in adult patients with suspected Meckel’s diverticulum and indefinite diagnostic imaging workup, including negative technetium 99m pertechnetate scintigraphy (known as the Meckel’s scan).

The manuscript is well written. The most common cause of obscure gastrointestinal bleeding is gastrointestinal vascular malformation. Meckel’s diverticulum, however, is a clinically important condition. Of 114 patients who underwent double-balloon enteroscopy, 4 cases of Meckel’s diverticulum were diagnosed and are described by this study.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty Type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of Origin: Brazil

Peer-Review Report Classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Chung DKV, Figueiredo PN, Vija L S- Editor: Qiu S L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Sagar J, Kumar V, Shah DK. Meckel’s diverticulum: a systematic review. J R Soc Med. 2006;99:501-505. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 171] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Soltero MJ, Bill AH. The natural history of Meckel’s Diverticulum and its relation to incidental removal. A study of 202 cases of diseased Meckel’s Diverticulum found in King County, Washington, over a fifteen year period. Am J Surg. 1976;132:168-173. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 269] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 231] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Cullen JJ, Kelly KA, Moir CR, Hodge DO, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ. Surgical management of Meckel’s diverticulum. An epidemiologic, population-based study. Ann Surg. 1994;220:564-568; discussion 568-569. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Park JJ, Wolff BG, Tollefson MK, Walsh EE, Larson DR. Meckel diverticulum: the Mayo Clinic experience with 1476 patients (1950-2002). Ann Surg. 2005;241:529-533. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 347] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 322] [Article Influence: 16.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Fukushima M, Kawanami C, Inoue S, Okada A, Imai Y, Inokuma T. A case series of Meckel’s diverticulum: usefulness of double-balloon enteroscopy for diagnosis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2014;14:155. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 31] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ymaguchi M, Takeuchi S, Awazu S. Meckel’s diverticulum. Investigation of 600 patients in Japanese literature. Am J Surg. 1978;136:247-249. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Paulsen SR, Huprich JE, Fletcher JG, Booya F, Young BM, Fidler JL, Johnson CD, Barlow JM, Earnest F. CT enterography as a diagnostic tool in evaluating small bowel disorders: review of clinical experience with over 700 cases. Radiographics. 2006;26:641-657; discussion 657-662. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 326] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 345] [Article Influence: 19.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Spottswood SE, Pfluger T, Bartold SP, Brandon D, Burchell N, Delbeke D, Fink-Bennett DM, Hodges PK, Jolles PR, Lassmann M. SNMMI and EANM practice guideline for meckel diverticulum scintigraphy 2.0. J Nucl Med Technol. 2014;42:163-169. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kotha VK, Khandelwal A, Saboo SS, Shanbhogue AK, Virmani V, Marginean EC, Menias CO. Radiologist’s perspective for the Meckel’s diverticulum and its complications. Br J Radiol. 2014;87:20130743. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 37] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Tanaka Y, Motomura Y, Akahoshi K, Nakama N, Osoegawa T, Kashiwabara Y, Chaen T, Higuchi N, Kubokawa M, Nishida K. Capsule endoscopic detection of bleeding Meckel’s diverticulum, with capsule retention in the diverticulum. Endoscopy. 2010;42 Suppl 2:E199-E200. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | He Q, Zhang YL, Xiao B, Jiang B, Bai Y, Zhi FC. Double-balloon enteroscopy for diagnosis of Meckel’s diverticulum: comparison with operative findings and capsule endoscopy. Surgery. 2013;153:549-554. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 22] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Huang TY, Liu YC, Lee HS, Chu HC, Chen PJ, Weng JW, Fu CK, Hsu KF. Inverted Meckel’s diverticulum mimicking an ulcerated pedunculated polyp: detection by single-balloon enteroscopy. Endoscopy. 2011;43 Suppl 2 UCTN:E244-E245. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Olafsson S, Yang JT, Jackson CS, Barakat M, Lo S. Bleeding Meckel’s diverticulum diagnosed and treated by double-balloon enteroscopy. Avicenna J Med. 2012;2:48-50. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Fukushima M, Suga Y, Kawanami C. Successful endoscopic resection of inverted Meckel’s diverticulum by double-balloon enteroscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:e35. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 10] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |