Published online Apr 16, 2014. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v6.i4.144

Revised: March 6, 2014

Accepted: March 11, 2014

Published online: April 16, 2014

We are reporting a rare case of a patient with primary (AL) amyloidosis presenting with an acute non-variceal upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage in the absence of other systemic involvement. The case report involves a 58-year-old woman with significant cardiac history and hereditary blood disorder who came in complaining of abdominal pain and coffee-ground emesis for two days. Computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast revealed segmental wall thickening of the proximal jejunum with hyperdense, heterogenous luminal content. Similar findings were evident in the left lower small bowel region, suspicious for small bowel hematoma and the possibility of intraluminal clots. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy performed post resuscitation showed punctate, erythematous lesions throughout the stomach as well as regions of small bowel mucosa that appeared scalloped, ulcerated, and hemorrhaged on contact. Despite initial treatment for immunostain-positive focal cytomegalovirus gastritis, follow-up esophagogastroduodenoscopy after two months continued to demonstrate friable and irregular duodenal mucosa hinting at a different underlying etiology. Pathology reports from analyses of biopsy samples highlighted infiltration and expansion of the lamina propria and submucosa. Subsequent staining with congo red/crystal violet and appropriate subtyping established the diagnosis of AL (kappa)-type amyloidosis. The significance of this case lies in the fact that our patient did not have the typically seen diagnostic systemic involvements-namely of heart and kidneys-usually seen in primary (AL) amyloidosis patients. It was the persistent endoscopic findings and biopsy results which gave clues to the physicians regarding the possibility of an abnormal protein-deposition entity.

Core tip: This case report of a 58-year-old African-American woman with coffee-ground emesis highlights a rare instance where AL (kappa)-type amyloidosis presents as gastrointestinal hemorrhage in the absence of clinical disease elsewhere in the body. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy initially revealed punctate, erythematous lesions throughout the stomach as well as regions of small bowel mucosa that appeared scalloped, ulcerated, and hemorrhaged on contact. Patient was treated for cytomegalovirus gastritis based on biopsy results. However, repeat enteroscopy continued to demonstrate friable and irregular duodenal mucosa with pathology highlighting infiltration and expansion of the lamina propria and submucosa. Appropriate staining and subtyping established AL (kappa)-type amyloidosis.

- Citation: Ali MF, Patel A, Muller S, Friedel D. Rare presentation of primary (AL) amyloidosis as gastrointestinal hemorrhage without systemic involvement. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2014; 6(4): 144-147

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v6/i4/144.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v6.i4.144

Primary (AL) amyloidosis is an infrequent disorder and the exact incidence is unknown. In the United States, there is roughly 6 to 10 cases per million person-years[1]. The median age at diagnosis is 64 years. There is a male predominance with men accounting for 65% to 70% of patients[2].

Amyloidosis involves the extracellular deposition of protein fibrils. Primary (AL) amyloidosis, as diagnosed in our patient, is associated with monoclonal light chains in serum and or urine. The kidneys and heart are the most commonly involved organs. However, the nervous system, lungs, liver, soft tissue and the gastrointestinal (GI) tract can be involved as well[3].

The occurrence of clinically evident gastrointestinal involvement depends on the type of amyloidosis. While as many as 60% of patients with reactive amyloidosis display gastrointestinal disease, it appears far less common in AL amyloidosis.

A 58-year-old African-American woman with history of sickle cell disease, atrial fibrillation, Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome and AICD presented with epigastric pain, coffee-ground emesis for 2 d. Patient denied nausea, early satiety, constipation, or dysphasia. She was found to have a hemoglobin level of 4.5 g/dL and was positively orthostatic, consequently requiring fresh frozen plasma (FFP) and multiple units of packed red blood cells (RBCs). The patient was started on continuous IV proton pump inhibitor (PPI) and admitted to ICU for close monitoring.

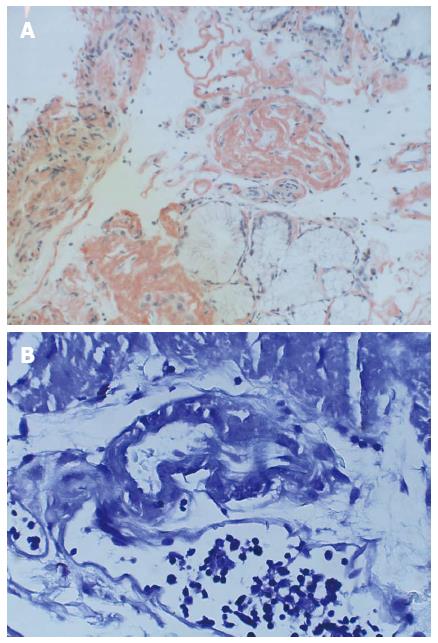

Computed tomography (CT) abdomen/pelvis with contrast showed segmental wall thickening of the proximal jejunum with hyperdense, heterogenous luminal content. Similar findings were evident in the left lower small bowel region, raising suspicion for small bowel hematoma with the possibility of intraluminal clots. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy post-resuscitation revealed punctate, erythematous lesions throughout the stomach (including the cardia) as well as regions of small bowel mucosa that appeared scalloped, ulcerated, and hemorrhaged on contact. Biopsies suggested marked acute duodenitis with blood, fibrin, and acute inflammatory exudates, indicative of the bleeding site (Figure 1B). Immunostains of these samples indicating focally active gastritis were positive for cytomegalovirus (CMV). Treatment with Valganciclovir (900 mg every 12 h) for 21 d was initiated.

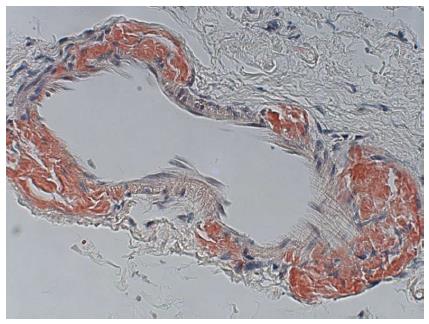

A repeat enteroscopy 2 mo later to assess for healing, continued to demonstrate friable and irregular duodenal mucosa (Figure 2). There was oozing from areas of scope contact and biopsy sites. Argon plasma coagulation was used to achieve hemostasis. Pathology underlined infiltration and expansion of the lamina propria and submucosa (Figure 1A) in addition to eosinophilic deposition around blood vessels (Figure 3). Immunostain was negative for CMV. Congo Red/Crystal Violet staining however, was positive, and appropriate subtyping subsequently established AL (kappa)-type amyloidosis.

The clinical diagnosis of gastrointestinal amyloidosis can be challenging in patients in whom the presence of this disease entity has not yet been established. Rarely does AL-amyloid present in the gastrointestinal tract as acute GI hemorrhage without other systemic symptoms[4]. Cardiac involvement, seen in 90% of the cases, is marked by congestive heart failure (CHF) and arrhythmias due to restrictive cardiomyopathy[5]. Diastolic dysfunction contributing to heart failure is apparent on echocardiography. Our patient had normal left ventricular systolic function and although she had abnormal left ventricular diastolic function, her E/A ratio was 1.3. The E/A ratio is usually greater than 2.0 in the restrictive cardiomyopathy associated with amyloidosis[6]. Additionally, the patient did not display any clinical signs of heart failure (e.g., lower extremity swelling of jugular venous distention). Renal insufficiency and/or nephrotic syndrome was also lacking in our patient.

Gastrointestinal manifestations appear to be less common in AL amyloidosis, with biopsy diagnosed disease and clinically apparent disease occurring in only 8% and 1% respectively of 769 patients in a retrospective review[7]. Despite the infrequency of gastrointestinal manifestations, the small intestine is the site of greatest deposition when there is involvement. Duodenal amyloidosis results in scalloped edges, duodenitis, ulcers, masses, hypotonia, and dilatation[8-10]. Endoscopic findings commonly include a fine granular appearance, polyps, erosions, ulcerations, and mucosal friability[11]. Clinical signs and symptoms may include hemorrhage, obstruction, and infarction amongst others.

Bleeding occurs as a presenting symptom in 25%-45% of patients with amyloidosis and may be caused by ischemia or infarction, by ulceration or an infiltrated lesion, or from generalized oozing without a particular source[12]. Endoscopy shows diffuse involvement, such as esophagitis and gastritis, more often than discrete lesions, as observed in our patient.

A 58-year-old African-American woman with history of sickle cell disease, atrial fibrillation, Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome and AICD presented with epigastric pain, coffee-ground emesis for 2 d.

Tenderness to palpation in the epigastric region on abdominal exam.

Multiple myeloma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, Amyloidosis, Gastritis.

Hemoglobin 4.5 g/dL; Hematocrit 13.4%; INR 2.15.

CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis showed marked segmental wall thickening of the proximal jejunum and parts of the small bowel, with hyperdense, heterogenous walls/luminal content.

Small bowel biopsy (duodenum) showed infiltration and expansion of the lamina propria and submucosa by Congo-red and crystal violet-positive amyloid.

Symptom control, e.g., blood transfusion/fluid resuscitation, monitoring vitals.

AL-amyloid rarely presents in the gastrointestinal tract as acute GI hemorrhage without other systemic symptoms.

The E/A ratio is a marker of the function of the left ventricle of the heart and is calculated on echocardiography with abnormalities indicative of diastolic dysfunction.

This case report highlights the importance of endoscopic findings and biopsy revelations in making a diagnosis of amyloidosis in patients without other systemic manifestations.

The paper is well written and reports an interesting case.

P- Reviewers: Dingli D, Marco M S- Editor: Song XX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang DN

| 1. | Kyle RA, Linos A, Beard CM, Linke RP, Gertz MA, O’Fallon WM, Kurland LT. Incidence and natural history of primary systemic amyloidosis in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1950 through 1989. Blood. 1992;79:1817-1822. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Kyle RA, Gertz MA. Primary systemic amyloidosis: clinical and laboratory features in 474 cases. Semin Hematol. 1995;32:45-59. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Madsen LG, Gimsing P, Schiødt FV. Primary (AL) amyloidosis with gastrointestinal involvement. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:708-711. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Spier BJ, Einstein M, Johnson EA, Zuricik AO, Hu JL, Pfau PR. Amyloidosis presenting as lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage. WMJ. 2008;107:40-43. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Nihoyannopoulos P, Dawson D. Restrictive cardiomyopathies. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2009;10:iii23-iii33. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Boufidou A, Mantziari L, Paraskevaidis S, Karvounis H, Nenopoulou E, Manthou ME, Styliadis IH, Parcharidis G. An interesting case of cardiac amyloidosis initially diagnosed as hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Hellenic J Cardiol. 2010;51:552-557. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Menke DM, Kyle RA, Fleming CR, Wolfe JT, Kurtin PJ, Oldenburg WA. Symptomatic gastric amyloidosis in patients with primary systemic amyloidosis. Mayo Clin Proc. 1993;68:763-767. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | Chang SS, Lu CL, Tsay SH, Chang FY, Lee SD. Amyloidosis-induced gastrointestinal bleeding in a patient with multiple myeloma. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;32:161-163. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | Hurlstone DP. Iron-deficiency anemia complicating AL amyloidosis with recurrent small bowel pseudo-obstruction and hindgut sparing. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;17:623-624. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Yousuf M, Akamatsu T, Matsuzawa K, Katsuyama T, Sugiyama A, Ikeda S, Kiyosawa K, Furuta S. Al-type generalized amyloidosis showing a solitary duodenal tumor. Hepatogastroenterology. 1992;39:267-269. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Tada S, Iida M, Iwashita A, Matsui T, Fuchigami T, Yamamoto T, Yao T, Fujishima M. Endoscopic and biopsy findings of the upper digestive tract in patients with amyloidosis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1990;36:10-14. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 12. | Ebert EC, Nagar M. Gastrointestinal manifestations of amyloidosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:776-787. [Cited in This Article: ] |