Published online May 16, 2012. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v4.i5.180

Revised: November 16, 2011

Accepted: April 27, 2012

Published online: May 16, 2012

AIM: To assess the efficacy and safety of endoscopic papillary large balloon dilation after biliary sphincterotomy for difficult bile duct stones retrieval.

METHODS: Retrospective review of consecutive patients submitted to the technique during 18 mo. The main outcomes considered were: efficacy of the procedure (complete stone clearance; number of sessions; need of lithotripsy) and complications.

RESULTS: A total of 30 patients with a mean age of 68 ± 10 years, 23 female (77%) and 7 male (23%) were enrolled. In 10 patients, a single stone was found in the common bile duct (33%) and in 20 patients multiple stones (67%) were found. The median diameter of the stones was 17 mm (12-30 mm). Dilations were performed with progressive diameter Through-The-Scope balloons (up to 12, 15) or 18 mm. Complete retrieval of stones was achieved in a single session in 25 patients (84%) and in two sessions in 4 patients (13%). Failure occurred in 1 case (6%). Mechanical lithotripsy was performed in 6 cases (20%). No severe complications occurred. One patient (3%) had mild-grade post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) pancreatitis.

CONCLUSION: Endoscopic balloon dilatation with a large balloon after endoscopic sphincterotomy is a safe and effective technique that could be considered an alternative choice in therapeutic ERCP.

- Citation: Rebelo A, Ribeiro PM, Correia AP, Cotter J. Endoscopic papillary large balloon dilation after limited sphincterotomy for difficult biliary stones. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2012; 4(5): 180-184

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v4/i5/180.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v4.i5.180

The basic principle of common bile duct stone extraction involves destruction or dilation of the bile duct orifice. Endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST) has been accepted as the standard management for stone removal from the bile duct since its first description in 1974[1], however, it is associated with complications such as haemorrhage, pancreatitis, perforation, and recurrent infection of the biliary tree; it also causes permanent functional loss of the sphincter of Oddi[1-3]. Endoscopic papillary balloon dilation (PBD) was introduced by Staritz et al[4] in 1983 and has been advocated as an alternative to EST in selected patients with bile duct stones, despite a few reports of an unacceptably high risk of pancreatitis[4-10]. The main advantage of this technique is that it does not involve cutting the biliary sphincter. Therefore, acute complications, such as haemorrhage or perforation may be less likely, and the function of the biliary sphincter may be preserved. Regardless of the theoretical merits of conventional PBD, one of the major limitations is the difficulty of removing larger stones because the biliary opening is not enlarged to the same degree as with EST[11]. To overcome these limitations, Ersoz et al[12] in 2003, introduced PBD with a large balloon after EST for the removal of large (≥ 15 mm) bile duct stones that are often difficult to remove with standard methods. They reported that PBD after limited EST was more effective for the retrieval of large stones and that it shortened the procedure time. This technique combines the advantages of EST and PBD by increasing the efficacy of stone extraction while minimizing complications of both EST and PBD alone[13].

In our study, we performed dilation of the sphincter with large Through-The-Scope (TTS) balloons (12-18 mm diameter) after limited EST. We analysed the efficacy, considering as primary endpoint the success rate of complete removal of stones in a single endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) session, and as secondary endpoints the number of ERCP sessions required for complete stone removal and the frequency of use of mechanical lithotripsy. Safety was evaluated by assessing the complications of the procedure.

From March 2009 to November 2010, a total of 30 patients were enrolled. All patients met the following selection criteria: (1) referral for ERCP by symptoms related to bile duct stones; (2) 18 years of age or older; (3) informed consent obtained before ERCP; (4) difficult bile duct stones visualized at ERCP (considered when ≥ 15 mm in diameter and/or when multiple); and (5) deep cannulation of the bile duct achieved without pre-cut. Exclusion criteria included: acute pancreatitis (severe epigastric pain combined with serum amylase more than three times the upper normal limit), acute cholecystitis (localized pain in the right upper abdomen, fever, and a thickened gallbladder wall on ultrasonography), which could compromise the assessment of procedure-related complications, or a history of previous biliary surgery (except cholecystectomy), haemostatic disorders, intrahepatic stone diseases, concomitant pancreatic or biliary malignant disorders.

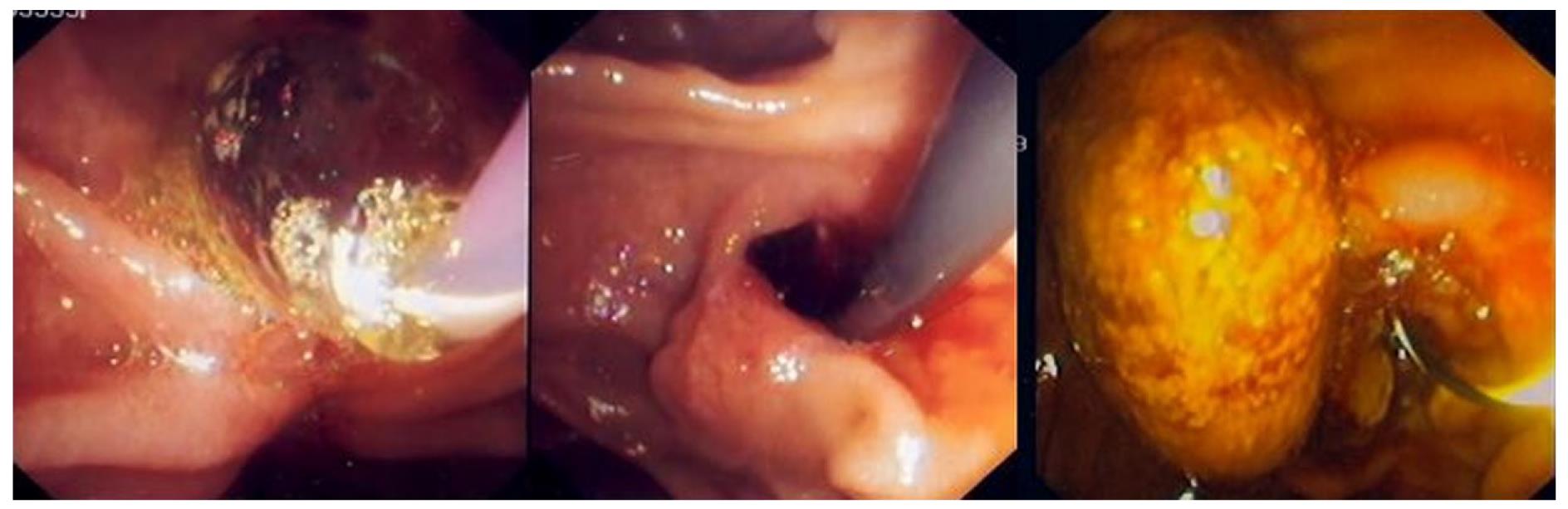

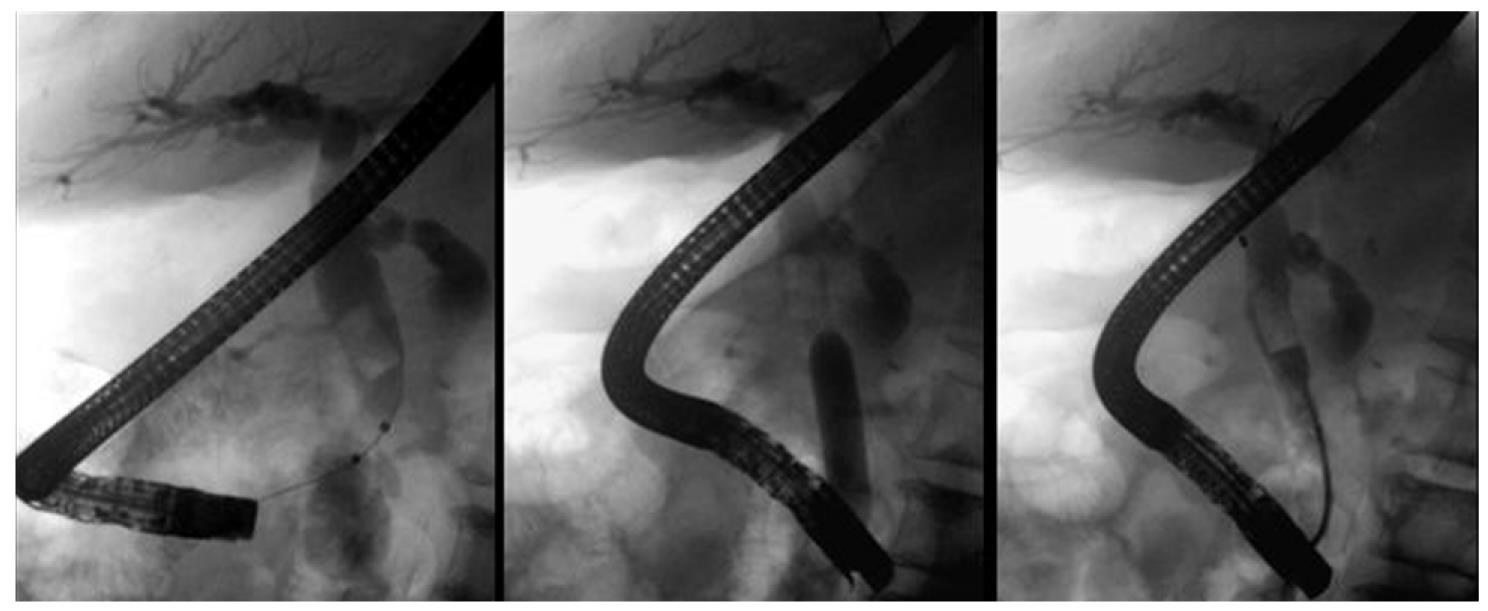

All the exams were performed with Olympus® TJF 160 VR and TJF 145 side-viewing endoscopes. Patients were under conscious sedation, performed by an anaesthesiologist. Prophylactic antibiotics were not routinely given. To decrease duodenal peristalsis, 20 mg butylscopolamine was administered intravenously when needed. The major papilla was located and the bile duct was deeply cannulated preferentially with a sphincterotome (Papillotomy knife, wire guided type, Olympus®). A diagnostic cholangiogram was obtained by injection of a diluted contrast medium. EST was performed over a 0.035 in guide wire (Hydra Jag wire TM guide wire, Boston Scientific Corp.®). After that, a 12 mm to 18 mm TTS balloon catheter for oesophageal/pyloric dilation (CRETM wire-guided balloon dilatation catheter, Boston Scientific Microvasive®) was passed over the guide wire and positioned across the papilla. Each balloon was gradually expanded to 12-18 mm with the instillation of diluted contrast medium, depending on the maximal diameter of the CBD, measured by cholangiography. The sphincter was considered adequately dilated when the waist in the balloon had disappeared completely. The fully expanded balloon was maintained in position for 60 s and then deflated and removed (Figure 1). After EBD, the stones were retrieved using a Dormia basket (WebTM extraction basket, Wilson-Cook Medical Inc.®) and/or a retrieval balloon catheter (System single use triple lumen stone extraction balloon, Olympus®). When strictly necessary, mechanical lithotripsy (BML-4Q, Olympus; Fusion Lithotripsy Basket, Wilson-Cook Medical®) was performed to fragment the stones prior to extraction from the bile duct. Complete stone removal was documented with a final cholangiogram (Figure 2). If stones were still present, a biliary plastic double pigtail stent was placed and a second ERCP was planned within 4-6 wk.

Stone size and number were documented on the initial cholangiogram during ERCP. Stone size was assessed by comparing the largest stone diameter with the diameter of the endoscope, measured on the X-ray image.

The primary endpoint was the success rate of complete removal of stones in the initial ERCP session. The secondary endpoints included the number of ERCPs until achievement of complete stone extraction, frequency of mechanical lithotripsy and complications such as bleeding, pancreatitis, cholangitis, and perforation. To assess these complications, blood samples for complete blood count, liver function test, amylase and lipase concentrations and C-reactive protein level were taken 24 h after the procedure. Post-ERCP pancreatitis was defined as persistent abdominal pain of more than 24 h duration associated with elevation of serum amylase more than three times the upper normal limit. Bleeding complications were considered when a decrease in haemoglobin concentration of > 2 g/dL was seen or evidence of clinical bleeding after the procedure, such as melena or hematemesis. Cholangitis was defined as a fever accompanied by jaundice and right upper quadrant pain. All complications were classified and graded according to the 1991 consensus guidelines[14]. After removal of the stones, ductal clearance was confirmed with a balloon catheter cholangiogram at the end of the procedure.

For statistical analysis we used the SPSS for Mac software (version 18.0). Data are presented as the mean ± SD or median with range. Categorical parameters were compared using χ2 or Fisher’s exact tests, while continuous variables were analysed by Student’s t test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

As described in Table 1, between March/2009 and September/2010, a total of 30 patients with a mean age of 68 ± 10 years, 23 female (77%) and 7 male (23%) were enrolled in the study.

| Mean age (yr) | 68 ± 10 |

| Gender (M/F) | 7/23 |

| Stones | |

| Single | 10 (33%) |

| Multiple | 20 (67%) |

| Median diameter (mm) | 17(12-30) |

| Periampullary diverticulum | 7 (23%) |

Twenty-six patients (86%) were submitted to EST followed by PBD, 2 required enlargement of previous EST and PBD (7%) and in 2 only PBD (7%) was performed since these patients had a previous EST with adequate dimensions.

In 10 patients a single stone in the CBD (33%) was found and in 20 patients multiple stones (67%) were found. The median diameter of the stones was 17 mm (range 12-30 mm). In 7 cases (23%), the papilla was peridiverticular, although accessible.

The dilations were performed with progressive diameter TTS balloons: 8 up to 12 mm (27%), 9 up to 13.5 mm (30%), 10 up to 15 mm (33%), 2 up to 16.5 mm (7%) and 1 up to 18 mm (3%).

In 29 patients (97%), endoscopic balloon dilation (EBD) of the biliary sphincter was successful and complete retrieval of bile duct stones was achieved. Failure occurred in 1 case (6%) due to impossibility in removing or capturing a 25 mm stone, even with a lithotripsy basket. Successful stone removal in one ERCP session was accomplished in 25 patients (84%). In 4 patients (13%) complete stone removal was possible in a second procedure performed within 4-6 wk. The stone removal rate according to stone size and number is described in Table 2. Mechanical lithotripsy was necessary in six patients (20%), allowing complete stone removal in the same procedure. The use of mechanical lithotripsy according to stone size and number is described in Table 3.

| Complete removal(with one ERCP) | Incomplete removal/failure | P | ||

| Stones | Single | 9 (90%) | 1 (10%) | NS |

| Multiple | 16 (80%) | 4 (20%) | ||

| Median diameter (mm) | 15 | 23 | 0.001 | |

| Use of lithotripsy | P | |||

| Yes | No | |||

| Stones | Single | 1 (10%) | 9 (90%) | 0.02 |

| Multiple | 5 (25%) | 15 (75%) | ||

| Median diameter (mm) | 16 | 17 | NS | |

In our study group, only one patient developed mild-grade post-ERCP pancreatitis that resolved with conservative treatment in 72 h. Haemorrhage did not occur in any of the patients. In 3 cases, minor oozing that spontaneously stopped during the procedure was noted. Fatal complications such as perforation or severe pancreatitis did not occur. An asymptomatic elevation of serum amylase/lipase was noted in 27% (8/30) of the patients and isolated abdominal pain occurred in 3 patients (10%). The elevated serum amylase/lipase usually normalized within 24-48 h after the procedure and did not affect the clinical course of the patients.

EBD has been reported to be an effective and safe method to access the bile duct for retrieval of common bile duct stones[13,15-17]. Specifically, EBD is recommended in patients with coagulation defects[13]. However, the use of conventional EBD is restricted to patients with small stones (less than 10 mm in diameter) since balloon dilation does not enlarge the sphincter to the same extent as EST. Concerns surrounding EBD are primarily due to the diameter of the balloon catheter and the associated risk of pancreatitis. EST is the most commonly used technique to access the bile duct in order to treat biliary stones. However, a large EST is associated with complications that in a few cases can be serious, such as perforation or severe haemorrhage[5,15]. Additionally, in difficult bile stones, EST alone does not allow complete stone extraction in some cases. In fact, in difficult cases complete stone extraction is only possible after the use of mechanical lithotripsy and, usually, involving multiple procedures.

To obviate these problems, Ersoz, in 2003, described the combined EST+EBD technique. This was the method performed in our study. The sphincterotomy performed previous to EBD allowed us to control the choledochal direction during dilation, straightening the distal part of the CBD. With this modified EBD procedure, we achieved greater access to the bile duct (12-18 mm) compared to conventional EBD of around 10 mm in diameter. The combination of these techniques creates a large orifice facilitating removal of large or multiple stones with less chance of impaction in the distal bile duct[15]. In our study, the overall technical success of bile duct stone retrieval was 97%, and the success rate of complete stone retrieval in a single ERCP session (83%) was comparable to previous reports which ranged from 80% to 100%[10-15]. Considering that the average diameter of the bile duct stones was 17 mm, this outcome is clinically acceptable. In addition, mechanical lithotripsy was required in only 6 cases (20%), all of which had stones > 15 mm in diameter.

When assessing the relationship between efficacy, the number of bile duct stones and their median diameter, only the size (larger stones, mean diameter 23 mm) was associated with incomplete removal or failure (P = 0.001); the number of stones (single versus multiple) did not influence the success of the technique (Table 2). According to the literature, the use of lithotripsy alone (without balloon dilation) is required in up to 25% of cases of difficult CBD stones[16,17]. In our series, mechanical lithotripsy was required in only 20% of patients who underwent large PBD after EST and it was required in only a few cases of single stones (10%; P = 0.02) (Table 3). However, these points of discussion should be validated with larger sized subgroups.

With respect to the complications normally associated with EBD, post-procedural pancreatitis is highly disputed. Even though Disario et al[8,9] reported that post-EBD pancreatitis developed in 14% of their patients with 2 fatal cases, other studies have reported that the post-EBD risk of pancreatitis is comparable to the risk associated with conventional EST. In theory, the risk of pancreatitis with EBD seems to be related to the pressure load on the orifice of the main pancreatic duct during balloon dilation. That is why EST prior to EBD could prevent pressure overload on the main pancreatic duct and consequently prevent post-EBD pancreatitis. In this study, we performed EST of the bile duct to control the choledochal direction of balloon dilation and prevent pressure overload on the orifice of the main pancreatic duct and we reported only one case of mild-grade post-ERCP pancreatitis. However, it is still not clear how large the sphincterotomy performed must be in order to achieve the apparent reduction in pancreatitis risk with large balloon dilation[15,17]. Regarding the risk of haemorrhage, this sequential technique has been shown to be as safe as conventional EBD. As in other series[13,15-19], in ours, we did not have any cases of important haemorrhage. Another issue to consider during EBD with a large balloon is the risk of perforation of the duodenum. However, this risk is controlled, as during the ballooning, the endoscopist is able to monitor the dilation status of the ampulla, both endoscopically and by using fluoroscopy. Additionally, the EST performed previously has the capacity to orientate the correct direction of the dilation and control the impact of its radial force. Hence, the theoretical risk of perforation is very low[13-18]. Again, we had no cases of this complication.

Unlike balloon dilation as a substitute for sphincterotomy, endoscopic papillary large balloon dilation is rapidly catching on as a useful technique for large or difficult bile duct stones in patients with dilated bile ducts, when performed complementary to limited EST.

In conclusion, as reported by other authors[15-19], our study showed that endoscopic papillary large balloon dilation appears to be a safe and effective technique for the removal of large bile duct stones and should be considered in the management of difficult bile duct stones.

Endoscopy is accepted as a first treatment modality in the management of extrahepatic bile duct. Approximately 10%-15% of large or multiple stones cannot be retrieved individually using conventional means such as balloon, basket, with or without mechanical lithotripsy. Therefore, other endoscopic stone removal methods should be carefully studied and considered as options in these cases.

It remains a challenge to define the most effective and safe techniques for difficult bile duct stones retrieval.

Endoscopic papillary large balloon dilation after limited endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy (EST) is an alternative technique for the removal of large or difficult stones from the common bile duct; it appears to combine the advantages of EST and papillary balloon dilation (PBD) by increasing the efficacy of stone extraction while minimizing the complications of each technique. Although it was originally described some years ago and a number of studies have been published, the issues concerning this method are still controversial.

The study showed that endoscopic papillary large balloon dilation appears to be a safe and effective technique for removal of large bile duct stones and should be considered in the management of difficult bile duct stones. Additional major controlled studies should be performed to support this.

Endoscopic papillary large balloon dilation is a modified technique that consists of PBD after limited EST. Bile duct stones were considered difficult when they were ≥ 15 mm in diameter and/or multiple.

This is a small retrospective and descriptive study and therefore has its limitations. The authors consider that this technique is a valid option and should be considered in the management of difficult bile duct stones.

Peer reviewer: Wai-Keung Chow, Dr., Division of Gastroenterology, China Medical University Hospital, No. 2, Yu-Der Rd., Taichung 407, Taiwan, China

S- Editor Yang XC L- Editor Webster JR E- Editor Yang XC

| 1. | Classen M, Demling L. [Endoscopic sphincterotomy of the papilla of vater and extraction of stones from the choledochal duct (author's transl)]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1974;99:496-497. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 469] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 381] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kawai K, Akasaka Y, Murakami K, Tada M, Koli Y. Endoscopic sphincterotomy of the ampulla of Vater. Gastrointest Endosc. 1974;20:148-151. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 514] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 438] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Freeman ML, Nelson DB, Sherman S, Haber GB, Herman ME, Dorsher PJ, Moore JP, Fennerty MB, Ryan ME, Shaw MJ. Complications of endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:909-918. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1716] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1607] [Article Influence: 57.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 4. | Staritz M, Ewe K, Meyer zum Büschenfelde KH. Endoscopic papillary dilation (EPD) for the treatment of common bile duct stones and papillary stenosis. Endoscopy. 1983;15 Suppl 1:197-198. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 24] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Bergman JJ, Rauws EA, Fockens P, van Berkel AM, Bossuyt PM, Tijssen JG, Tytgat GN, Huibregtse K. Randomised trial of endoscopic balloon dilation versus endoscopic sphincterotomy for removal of bileduct stones. Lancet. 1997;349:1124-1129. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 292] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 287] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Yasuda I, Tomita E, Enya M, Kato T, Moriwaki H. Can endoscopic papillary balloon dilation really preserve sphincter of Oddi function? Gut. 2001;49:686-691. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 164] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | May GR, Cotton PB, Edmunds SE, Chong W. Removal of stones from the bile duct at ERCP without sphincterotomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1993;39:749-754. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 67] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Arnold JC, Benz C, Martin WR, Adamek HE, Riemann JF. Endoscopic papillary balloon dilation vs. sphincterotomy for removal of common bile duct stones: a prospective randomized pilot study. Endoscopy. 2001;33:563-567. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 95] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Bergman JJ, Tytgat GN, Huibregtse K. Endoscopic dilatation of the biliary sphincter for removal of bile duct stones: an overview of current indications and limitations. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1998;225:59-65. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kozarek RA. Balloon dilation of the sphincter of Oddi. Endoscopy. 1988;20 Suppl 1:207-210. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 74] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Baron TH, Harewood GC. Endoscopic balloon dilation of the biliary sphincter compared to endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy for removal of common bile duct stones during ERCP: a metaanalysis of randomized, controlled trials. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1455-1460. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 243] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 249] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ersoz G, Tekesin O, Ozutemiz AO, Gunsar F. Biliary sphincterotomy plus dilation with a large balloon for bile duct stones that are difficult to extract. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:156-159. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 272] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 289] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Bang S, Kim MH, Park JY, Park SW, Song SY, Chung JB. Endoscopic papillary balloon dilation with large balloon after limited sphincterotomy for retrieval of choledocholithiasis. Yonsei Med J. 2006;47:805-810. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 48] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Cotton PB, Lehman G, Vennes J, Geenen JE, Russell RC, Meyers WC, Liguory C, Nickl N. Endoscopic sphincterotomy complications and their management: an attempt at consensus. Gastrointest Endosc. 1991;37:383-393. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1890] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1934] [Article Influence: 58.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Attam R, Freeman ML. Endoscopic papillary large balloon dilation for large common bile duct stones. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2009;16:618-623. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 58] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Itoi T, Itokawa F, Sofuni A, Kurihara T, Tsuchiya T, Ishii K, Tsuji S, Ikeuchi N, Moriyasu F. Endoscopic sphincterotomy combined with large balloon dilation can reduce the procedure time and fluoroscopy time for removal of large bile duct stones. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:560-565. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 112] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Lee DK, Jahng JH. Alternative methods in the endoscopic management of difficult common bile duct stones. Dig Endosc. 2010;22 Suppl 1:S79-S84. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 24] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kim HG, Cheon YK, Cho YD, Moon JH, Park do H, Lee TH, Choi HJ, Park SH, Lee JS, Lee MS. Small sphincterotomy combined with endoscopic papillary large balloon dilation versus sphincterotomy. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:4298-4304. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 74] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 79] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Kochhar R, Dutta U, Shukla R, Nagi B, Singh K, Wig JD. Sequential endoscopic papillary balloon dilatation following limited sphincterotomy for common bile duct stones. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:1578-1581. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 15] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |