Published online Jun 14, 2018. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i22.2406

Peer-review started: March 10, 2018

First decision: April 11, 2018

Revised: April 18, 2018

Accepted: April 23, 2018

Article in press: April 23, 2018

Published online: June 14, 2018

A 61-year-old female patient with chronic hepatitis B virus infection was diagnosed with liposarcoma in a community hospital. Fine needle aspiration biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of well-differentiated liposarcoma. Abdominal computed tomographic angiography (CTA) showed that the mass adhered to and constricted the main trunk and branch of the superior mesenteric vein (SMV), especially the ileocolic vein, and collateral circulation was observed during the vascular reconstruction scan. The abdominal liposarcoma was resected. Because of the collateral circulation, devascularization of the SMV was attempted, and we resected the eroded SMV. The condition of the blood vessels was evaluated 20 d after surgery using CTA, which showed that the SMV had disappeared. Significant improvements in SMV collateral circulation and the inferior mesenteric vein were observed after vascular reconstruction. The patient had an uneventful postoperative course except for transient gastroplegia. Twenty months after surgery, the patient had a recurrence of liposarcoma. She underwent tumor resection to remove the distal small intestine and right hemicolon. We learned that (1) direct devascularization of the main SMV trunk without a vein graft is possible. The presence of collateral circulation can increase the success rate of patients undergoing radical surgery and prevent the occurrence of serious postoperative complications. In addition, (2) this case demonstrated the clinical value of 3D reconstruction.

Core tip: A large liposarcoma adhered to and constricted the main trunk and branches of the superior mesenteric vein (SMV). Because of the existence of the collateral circulation, which had been observed by computed tomographic angiography, we resected the eroded SMV and devascularized it without vein grafting. In the case, we were aware of the clinical value of 3D reconstruction, and we believed that the collateral circulation could replace the function of SMV. Moreover, the collateral circulation may have ensured this patient’s postoperative survival. However, the actual condition for the formation of collateral circulation must be explored further.

- Citation: Miao RC, Wan Y, Zhang XG, Zhang X, Deng Y, Liu C. Devascularization of the superior mesenteric vein without reconstruction during surgery for retroperitoneal liposarcoma: A case report and review of literature. World J Gastroenterol 2018; 24(22): 2406-2412

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v24/i22/2406.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v24.i22.2406

Although common as a soft tissue sarcoma, liposarcoma is a rare malignant tumor of embryogenic mesoderm origin that occurs in the extremities, the trunk, or the retroperitoneum and seldom in the digestive tract. Well-differentiated, myxoid, round cell, pleomorphic, and dedifferentiated are all histologic types of liposarcoma.

Retroperitoneal liposarcoma, which derives from mesenchymal rather than adipose tissue, has no obvious symptoms until the liposarcoma is large enough to compress the surrounding organs[1]. The 5-year survival rate for well-differentiated retroperitoneal liposarcoma is 83%[2]. However, it also has a high recurrence rate. Therefore, the primary treatment for retroperitoneal liposarcoma is complete resection of the tumor with wide margins, including excision of other organs. Complete resection of the tumor is difficult, usually due to the invasion of major organs or vessels that cannot be separated from the tumor.

Retroperitoneal liposarcoma clearance during surgery can be facilitated by resection of the vessels involved, especially the superior mesenteric vein (SMV) or the portal vein. SMV injuries are highly lethal, and the vessel is repaired during the resection of the main SMV[3]. The clinical course and consequences following resection of the main trunk of the SMV without reconstruction for giant retroperitoneal liposarcoma have not been reported. Here, we report a case of giant retroperitoneal liposarcoma with resection of the main trunk of the SMV without reconstruction, the postoperative course, and the radiographic findings following SMV resection. Treatment was a resection of a retroperitoneal liposarcoma.

A 61-year-old female patient with chronic hepatitis B virus infection was admitted to our clinic for surgical resection due to a computed tomography (CT) scan showing a large retroperitoneal mass. The mass was biopsied immediately in a community hospital, revealing a well-differentiated liposarcoma.

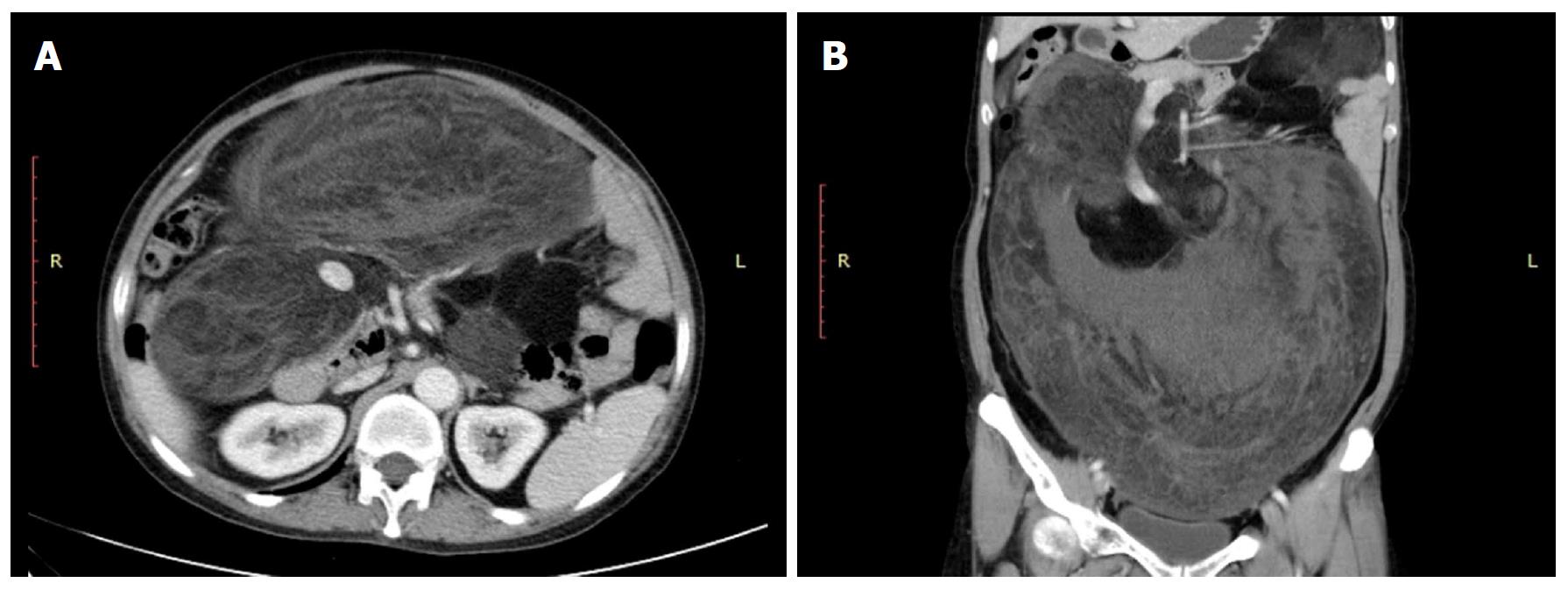

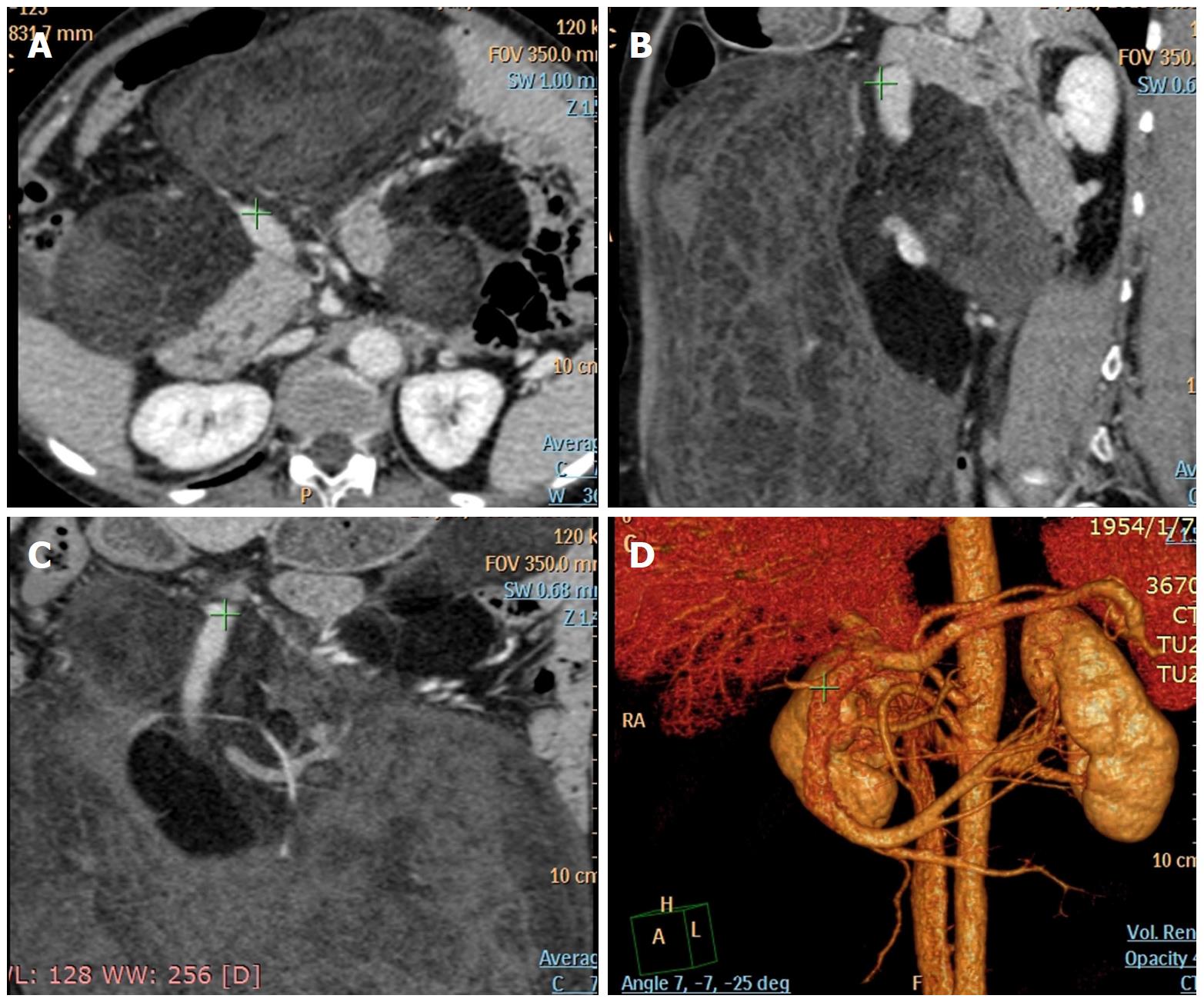

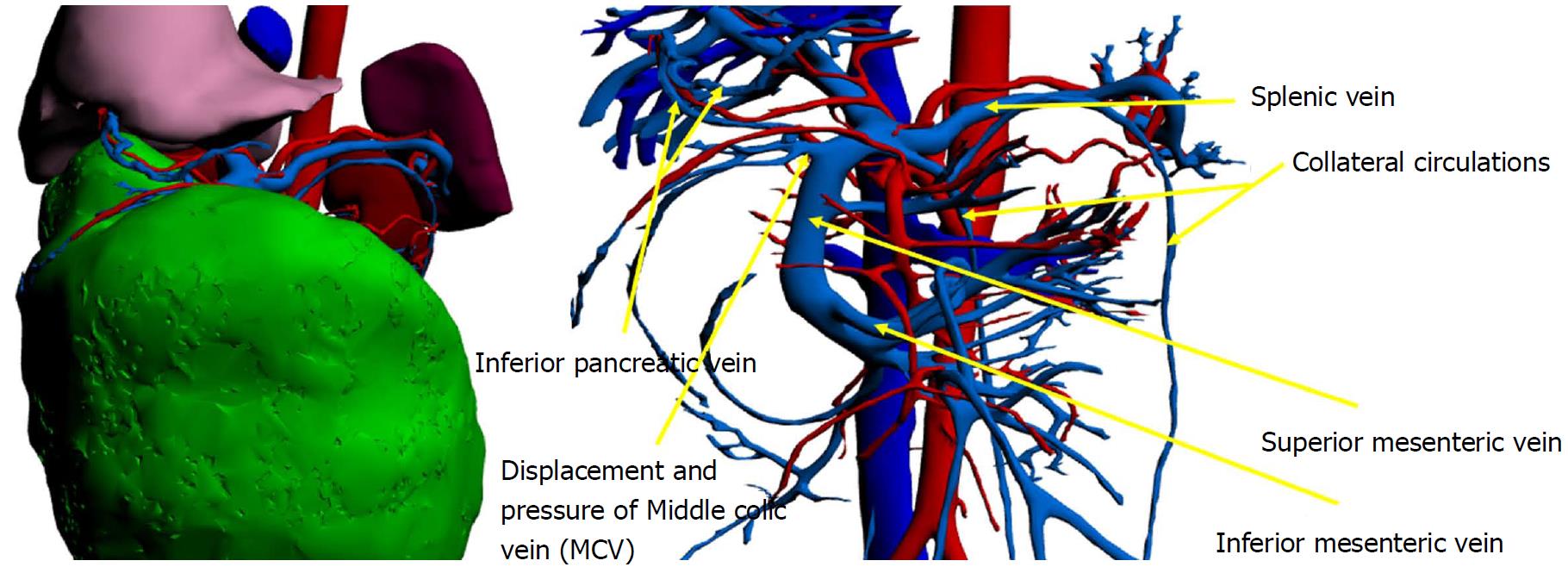

On admission, her medical history was unremarkable. Her physical examination revealed no major abnormalities except for mild epigastric abdominal pain. Laboratory investigations showed low albumin level (28 g/L) and positive HcAb. Tumor markers (CA19-9, CEA, CA125) were normal. Laboratory tests revealed the following transaminase levels: an aspartate aminotransferase (AST) of 17 U/L (normal, < 40 U/L), an alanine aminotransferase (ALT) of 11 U/L (normal, < 40 U/L), and a total bilirubin of 1.5 μmol/L (normal, 6-20.5 μmol/L). Abdominal and pelvic contrast-enhanced CT (Figure 1A and B) was performed and indicated a 118 mm × 258 mm × 303 mm soft tissue mass with mixed density containing fat. Abdominal computed tomographic angiography (CTA) showed that the mass adhered to and constricted the main trunk and branch of the SMV, especially the ileocolic vein; the right renal vein; and the inferior vena cava, and the plane parallel to the renal hilum was significantly compressed, with a slender renal vein (Figure 2A-D). Fortunately, renal dynamic imaging showed that the function of both kidneys was normal. Considering the complicated relationship between the tumor and compressed veins, we tried to perform vascular reconstruction. We observed that the middle colic vein (MCV) walked the tumor surface. Two slight veins that could not be anatomically named beginning at the SMV beneath the splenic-portal vein confluence were found (Figure 3). We hypothesized that the two veins were collateral vessels. The one collateral vessel collected blood coming from the left colon, and the other went to the retroperitoneum. The MCV showed displacement and did not supply the mass except for the confluence with the SMV. Interestingly, the MCV connected with the inferior pancreatic vein, which collects blood from the pancreas and stomach via the right gastroepiploic vein.

Due to the complicated organs that were involved, we discussed this case with a multidisciplinary team, including Gynecology, Urology, Radiology, and Gastroenterology. Because of the complexity of the vessel invasion, it was impossible to perform the retroperitoneal tumor dissection and to keep vessels intact. Ligation of the superior mesenteric vein was necessary. However, according to the imaging findings, we did not have a proper sized vein graft, because the tumor invaded SMV at this point. We were reluctant to use a synthetic graft because of the potential risk of graft infection and thrombosis. The SMV is the most important vein in abdomen, and it collects the blood from the abdominal organs and forms the portal vein together with the splenic veins. It carries abundant nutrients into the liver, and serves as a metabolic energy source for the liver itself. We noticed that the patient’s liver function did not show significant damage. This is unexpected given the long-term compression of the SMV. Therefore, we discussed the collateral circulation and suggested that vascular passage between the MCV and the inferior pancreatic vein could support complete venous return to the abdominal organs. In this case, the collateral vessels can ensure normal venous return for abdominal organs after resecting the SMV. A similar finding had been reported in a pancreaticoduodenectomy, despite possibly causing lethal consequences[4]. Therefore, the preferred choice of operation was surgical removal of the liposarcoma and invaded SMV. If the blood supply to the intestine was insufficient, the portal vein could be reconstructed.

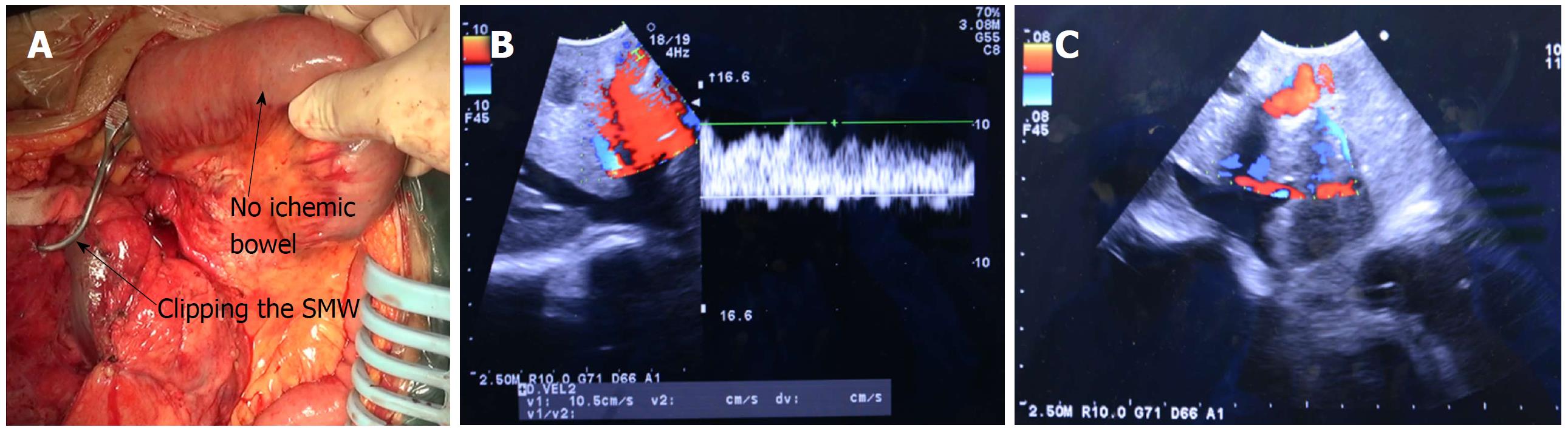

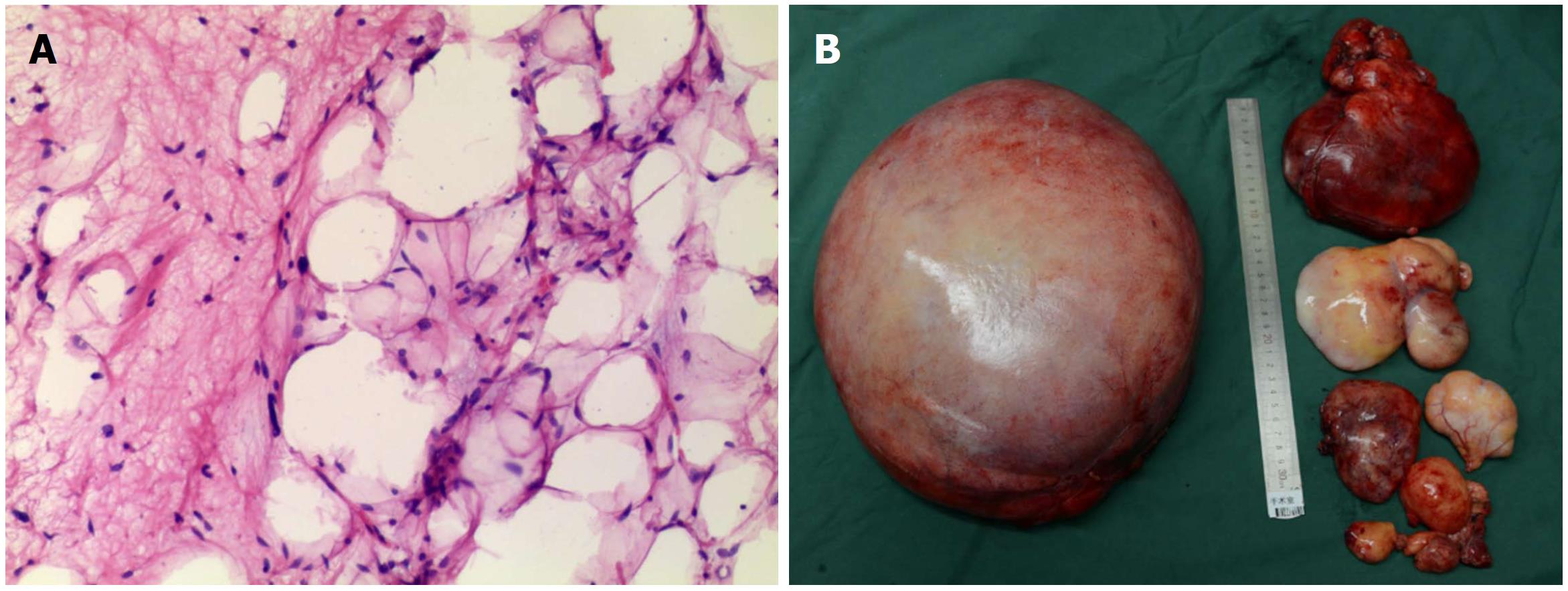

The patient had no surgical contraindication except for the low albumin level. Therefore, her albumin was increased to 30.6 g/L. The abdominal liposarcoma was resected. The portal vein and the splenic vein were free from the tumor. The base of the tumor (118 mm × 258 mm × 303 mm) was close to the CMV, which was easy to resect by cutting off the pedicle. Consistent with preoperative CT and CTA, we found during surgery that the tumor was supported by the SMV, whose normal anatomy had to be destroyed. We initially stripped the SMV from the tumor. Unfortunately, the SMV was adhered to the tumor, and it bled immediately when peeled away. Considering the preoperative plan, we tried to occlude the SMV by vessel clamp for 20 min and did not see bowel ischemia (Figure 4A). There were no changes to venous blood flow to the liver by Doppler and B-mode ultrasound (Figure 4B and C). In the end, the SMV and liposarcoma were resected simultaneously without graft substitutes, allowing for no change to the bowel or liver, and the MCV was retained and communicated with the branch of the inferior pancreatic vein. The final pathology report confirmed the diagnosis of well-differentiated liposarcoma (Figure 5A). Despite identifying only one liposarcoma before surgery, we found two larger masses and some smaller masses that were easy to remove (Figure 5B).

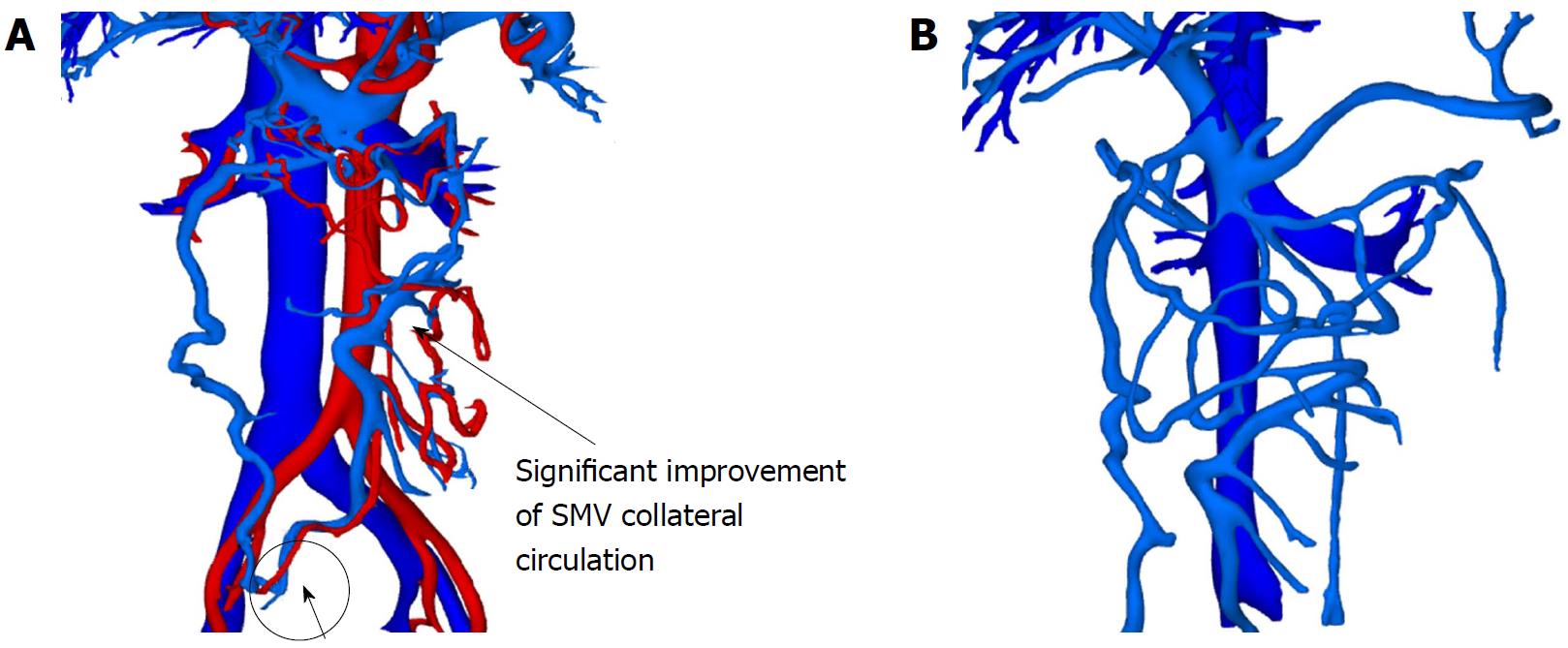

The condition of the blood vessels was evaluated for 20 d after surgery using CTA. We found that the SMV had disappeared. Significant improvement in collateral circulation was found from vascular reconstruction (Figure 6A). This collateral circulation helped venous blood completely return to the portal vein. On postoperative day (POD) 6, the patient experienced nausea and vomiting, suggesting postoperative complications of the ileus. The patient’s bowel sounds were weak, and her serum transaminase levels peaked (AST = 80 U/L, ALT = 103 U/L). Gastrointestinal decompression and enteral nutritional support were undertaken. Upper gastrointestinal radiography was performed to evaluate the recovering function of the alimentary canal. On POD 23, bowel function recovered. On POD 27, no abnormal signs were observed by CT scan. The patient was discharged on POD 29.

After 2 mo, the patient did not feel any discomfort, and the patient’s condition was evaluated by CTA and serum tumor marker levels. The results showed normal levels of AFP, CA125, and CA199. The collateral circulation had good blood supply (Figure 6B). For follow-up, the patient had a CT every 6 mo. After 20 mo, CT and CTA results showed a recurrence of liposarcoma. The numerous masses were of variable sizes and invaded the intestines. We had to remove the distal small intestine and right hemicolon. Short bowel syndrome did not occur after the operation. The patient was discharged on POD 27.

Liposarcomas are the second most common soft tissue sarcoma in adults after malignant fibrous histiocytoma and predominantly occur in the lower extremities and the retroperitoneum[5]. Although retroperitoneal liposarcomas are common, few international studies have reported a large tumor similar to our case. In the current case, the two liposarcomas were quite large, and the larger one constricted the main vasculature in the abdominal cavity, especially the SMV. Among patients with retroperitoneal liposarcomas, ours is the first case about resection of the SMV without revascularization. It is rare that vascular revascularization is not performed after the surgical removal of the SMV. Only one case in the previous literature reported use of this technique[4]. That patient was diagnosed with pancreatic head tumor and had formed multiple collateral circulations. The proximal SMV was invaded by the tumor. After neoadjuvant therapy, the tumor volume was reduced, relieving pressure on the portal vein, and the pancreatoduodenectomy was performed. At the beginning of the procedure, anastomosis of the superior mesenteric vein and portal vein was attempted, but, as occurred in our case, the distance was too great. The vascular reconstruction was denied by the surgeon because of the high risk of postoperative graft immunity and thrombosis. The anastomosis was performed between the splenic vein and the portal vein to relieve the reflux pressure of the portal vein, and the superior mesenteric vein was ligated. The patient recovered well after surgery. Regretfully, that patient died because of ascites 15 mo after surgery.

In pancreaticoduodenectomy, both the SMV and portal veins must be resected and reconstructed when the tumor invades the vein, in order to obtain R0 resection. During a common vein trauma, an anastomosis should be made to repair the vein. However, if the segment of the damaged vein is too long, the best choice is a vein graft, typically a synthetic graft because of the complex anticoagulant therapy after surgery[6]. Mobilizing the liver would weaken the tension in the anastomosis. Moreover, anastomotic thrombosis caused by revascularization is another postoperative complication. Previously, ligation of the SMV during pancreaticoduodenectomy due to anastomosis of the portal and splenic veins in a desperate situation that decompressed the mesenteric venous system was reported[4]. This study produced an interesting surgical option of deliberately breaking the SMV in cases where the SMV had been eroded. In the present case, because some collateral circulation was observed on the scan before the operation, venous collaterals secondary to the portal vein may have allowed the patient’s postoperative survival. The postoperative vascular reconstruction on POD 20 also showed significant improvement of collateral circulation, which had been much too slight on the preoperative scan. Therefore, we have evidence that the collateral circulation existed for a long time and may have been able to replace the SMV. However, the SMV resection without any reconstruction is a suitable option for special situations where another vessel can functionally replace the SMV. In this case, we had found collateral circulation by preoperative vascular reconstruction. This is the most sensitive method for detecting the formation of collateral circulation. However, its false negative rate (FNR) has not been seen in related studies. In addition, in this case, a vein graft was not performed because we considered the possibility of postoperative venous thrombosis. However, vein transplantation is still very necessary for patients without the observation of collateral circulation. Therefore, we believed that the possible collateral circulation reconstruction time and conditions need to be explored in further studies.

Abdominal veins may serve as collateral channels within the systemic circulation[7]. The presence of portosystemic collateral veins (PSCVs) is common in portal hypertension, which is defined as blood flow through a vessel or a vascular bed that is obstructed due to occlusion, as in extrahepatic portal vein obstruction (EHPVO), or distorted, as in liver cirrhosis. In the present case, due to the gradual growth of liposarcomas, the SMV was compressed slowly into a nonfunctional vein, whose function was replaced by collateral veins over a long time. In addition to PSCV, portoportal collateral vein (PPCV) pathways are frequently found in patients with EHPVO. Although SMV devascularization without reconstruction during surgery is not recommended, this case showed the possibility of success with the presence of PSCVs. Because tumor compression might contribute to abnormal blood vessels by causing displacement or applying pressure, high quality imaging examination is necessary. This case demonstrated the clinical value of 3D reconstruction. Medicine today is not an isolated discipline, rather it is improved with the aid of science and technology. In addition, removal of revascularization procedures during surgery reduces the likelihood of postoperative thrombosis. In this patient, the CMV was retained and communicated with the branch of the inferior pancreatic vein to ensure venous blood stream come from abdominal organs. There are many anatomic variations for the CMV. In recent years, two types of variation have been reported: (1) The CMV returns directly to the SMV; (2) The CMV and the right and left right colon veins return to the Henle’s trunk together. The confluence of the middle colonic vein with the inferior pancreatic duodenal vein has not been previously reported. This confluence may also be due to the anatomical variation formed by long-term tumor compression.

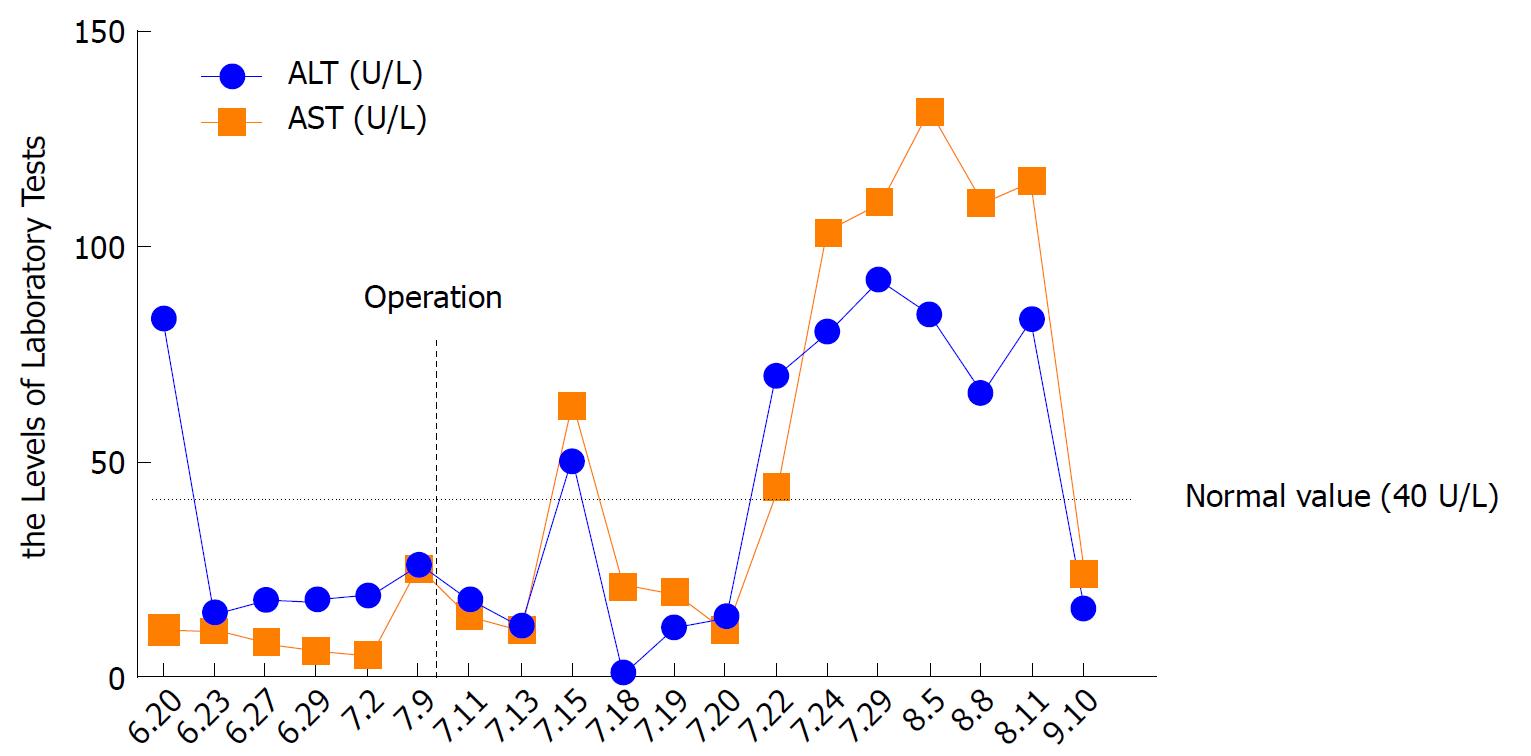

The ileus was the only postoperative complication in the gastrointestinal system. Because of the ileus, the patient’s serum transaminases (AST 80 U/L, ALT 103 U/L) were abnormally elevated on POD 13 (Figure 7). We hypothesized that the reduction of blood back to the liver and the blood flow stasis in the intestine contributed to the sudden liver disorder. The patient was treated with gastrointestinal decompression and nutritional support, and this complication was controlled before discharge from the hospital. One month postoperatively, the levels of transaminases had declined. Two months postoperatively, the levels of transaminases (AST = 16 U/L, ALT = 24 U/L) had returned to normal.

Twenty months after the first surgery, the patient had a recurrence of liposarcoma that was concerning. The prognosis of RPLS patients is highly variable. Some survive only a few months, whereas others can survive for decades. At present, there is a lack of medical evidence to help with determining prognosis. Some studies have found that the liposarcoma local recurrence rate 5 years after surgery is close to 50%, and as the follow-up time increases, the recurrence rate continues to rise slowly[8]. Today, there are no adjuvant therapy guidelines for the prevention of postoperative tumor recurrence[9]. In the present case, the patient did not receive adjuvant therapy. Postoperative radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and immunotherapy in patients with liposarcoma are still in the research phase. One report found that postoperative radiotherapy can reduce the local recurrence of RPLS, especially in pathological types with poor prognosis[10]. However, there is no effect on survival. Another study demonstrated that preoperative radiotherapy can improve the overall survival of patients[11]. Therefore, preoperative and postoperative adjuvant therapy for liposarcoma patients is necessary.

We are reporting this case in line with CARE Guidelines. We believe this case should be reported for future reference and research. The collateral circulation may have allowed this patient’s postoperative survival. However, the actual conditions for the formation of collateral circulation still need to be explored further.

This case was diagnosed as a huge retroperitoneal liposarcoma. The tumor size was large, and the tumor numbers were many. The invasion of blood vessels by the tumor was severe. In particular, the superior mesenteric vein, which is one of the most valuable veins in abdomen, had been eroded by tumors. No similar case report has been reported previously, and the research potential is enormous.

Before the patient came to our hospital, the pathological type was confirmed in the community hospital through the Fine needle aspiration biopsy, but the detailed diagnostic information of the tumor could not be clarified further in the community hospital due to technical problems. It is very necessary to run a computed tomographic angiography (CTA) test and vascular reconstruction techniques in such patients.

Patient was diagnosed clearly, no differential diagnosis

In this case, laboratory investigations showed low albumin level and positive HcAb. Tumor markers (CA19-9, CEA, CA125) levels were normal. The transaminase levels of AST, ALT, and total bilirubin were all within the normal range, showingthat the existence of the large retroperitoneal tumor did not cause damage to the liver. There may be other ways to ensure liver function besides the superior mesenteric vein.

Abdominal and pelvic contrast-enhanced computed tomography was performed and indicated a 118*258*303 mm soft tissue mass with mixed density containing fat. Abdominal CTA showed that the mass adhered to and constricted the main trunk and branch of the superior mesenteric vein (SMV), especially the ileocolic vein, the right renal vein and the inferior vena cava. The plane parallel to the renal hilum was significantly compressed, with a slender renal vein.

The pathology test confirmed the diagnosis of well-differentiated liposarcoma.

The preferred choice of treatment was surgical removal of the liposarcoma and invaded SMV. The abdominal liposarcoma was resected. The portal vein and the splenic vein were free from the tumor. After SMV interdiction, no bowel or liver ischemia was observed, and then the SMV and liposarcoma were resected simultaneously without graft substitutes.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of devascularization of the superior mesenteric vein without reconstruction applied to the resection of a retroperitoneal tumor.

We believe that this case should be reported for future reference and research. The collateral circulation may have ensured this patient’s postoperative survival. However, the actual conditions for the formation of collateral circulation still require additional examination.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Argentina

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

CARE Checklist (2013) statement: The authors have read the CARE Checklist (2013), and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the CARE Checklist (2013).

P- Reviewer: Podda M S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: Filipodia E- Editor: Yin SY

| 1. | Yamashita Y, Kurisu K, Kimura S, Ueno Y. Successful resection of a huge metastatic liposarcoma in the pericardium resulting in improvement of diastolic heart failure: a case report. Surg Case Rep. 2015;1:74. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Zhang WD, Liu DR, Que RS, Zhou CB, Zhan CN, Zhao JG, Chen LI. Management of retroperitoneal liposarcoma: A case report and review of the literature. Oncol Lett. 2015;10:405-409. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 23] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Asensio JA, Petrone P, Garcia-Nuñez L, Healy M, Martin M, Kuncir E. Superior mesenteric venous injuries: to ligate or to repair remains the question. J Trauma. 2007;62:668-675; discussion 675. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 50] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Tang J, Abbas J, Hoetzl K, Allison D, Osman M, Williams M, Zelenock GB. Ligation of superior mesenteric vein and portal to splenic vein anastomosis after superior mesenteric-portal vein confluence resection during pancreaticoduodenectomy - Case report. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2014;3:137-140. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Mani VR, Ofikwu G, Safavi A. Surgical resection of a giant primary liposarcoma of the anterior mediastinum. J Surg Case Rep. 2015;2015. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Jeon H, McHugh PP, Banerjee A, Gedaly R, Johnston TD, Ranjan D. The use of Dacron graft for cavo-cavostomy in orthotopic liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2008;85:651-653. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Pillai AK, Andring B, Patel A, Trimmer C, Kalva SP. Portal hypertension: a review of portosystemic collateral pathways and endovascular interventions. Clin Radiol. 2015;70:1047-1059. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 29] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lee ATJ, Thway K, Huang PH, Jones RL. Clinical and Molecular Spectrum of Liposarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:151-159. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 149] [Article Influence: 21.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lee HS, Yu JI, Lim DH, Kim SJ. Retroperitoneal liposarcoma: the role of adjuvant radiation therapy and the prognostic factors. Radiat Oncol J. 2016;34:216-222. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 15] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Park H, Lee S, Kim B, Lim do H, Choi YL, Choi GS, Kim JM, Park JB, Kwon CH, Joh JW. Tissue expander placement and adjuvant radiotherapy after surgical resection of retroperitoneal liposarcoma offers improved local control. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:e4435. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 6] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ecker BL, Peters MG, McMillan MT, Sinnamon AJ, Zhang PJ, Fraker DL, Levin WP, Roses RE, Karakousis GC. Preoperative radiotherapy in the management of retroperitoneal liposarcoma. Br J Surg. 2016;103:1839-1846. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 18] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |