Published online Jul 28, 2016. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i28.6547

Peer-review started: April 4, 2016

First decision: May 12, 2016

Revised: May 26, 2016

Accepted: June 28, 2016

Article in press: June 29, 2016

Published online: July 28, 2016

AIM: To assess the functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGID) prevalence in infants and toddlers.

METHODS: PubMed, EMBASE, and Scopus were searched for original articles from inception to February 2016. The literature search was made in accordance with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA). For inclusion, each study had to report epidemiological data of FGID on children up to 4 years old and contain standardized outcome Rome II or III criteria. The overall quality of included epidemiological studies was evaluated in accordance to Loney’s proposal for prevalence studies of health literature. Two reviewers assessed each study for inclusion and extracted data. Discrepancies were reconciled through discussion.

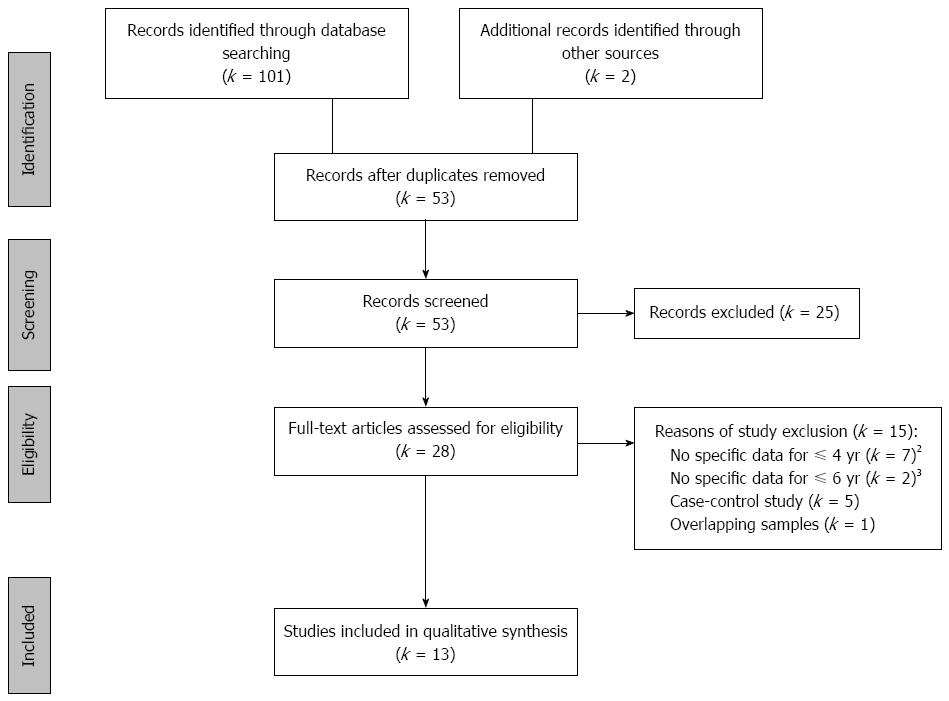

RESULTS: It was identified a total of 101 articles through the databases and two through the manual search. A total of 28 articles fulfilled the eligibility criteria. After reading the full articles, 13 of them were included in the present review. Twelve studies were written in English and one in Chinese, and published between 2004 and 2015. Eight articles (61.5%) were performed in Europe, three (23.1%) in America and two (15.4%) in Asia. Sample size varied between 45 and 9660 subjects. Cross-sectional frequency was reported in majority of studies (k = 9) and four studies prospectively followed the subjects. 27.1% to 38% of participants have met any of Rome’s criteria for gastrointestinal syndromes, of those 20.8% presented two or more FGID. Infant regurgitation and functional constipation were the most common FGID, ranging from less than 1% to 25.9% and less than 1% to 31%, respectively. Most included studies were of moderate to poor data quality with respect to absence of confidential interval for prevalence rate and inadequate sampling methods.

CONCLUSION: The scarcity and heterogeneity of FGID data call for the necessity of well-designed epidemiological research in different levels of pediatric practice and refinement of diagnostic.

Core tip: Epidemiological studies on functional gastrointestinal disorders in infants and toddlers provide variable prevalence rates in both pediatric outpatient and inpatient practice. A number of investigations and reviews have been conducted using Rome’s criteria for functional disorders to depict the magnitude of the problem, however, few investigations have reported meaningful results with adequate methodology. The current literature review suggested higher impact of pediatric feeding and defecation problems that affect very young children, respectively infant regurgitation and functional constipation.

- Citation: Ferreira-Maia AP, Matijasevich A, Wang YP. Epidemiology of functional gastrointestinal disorders in infants and toddlers: A systematic review. World J Gastroenterol 2016; 22(28): 6547-6558

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v22/i28/6547.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v22.i28.6547

Functional symptoms are corporal manifestations that arise in the absence of anatomic abnormality, inflammation, or tissue damage. Historical descriptions and theories on complex interaction between biological, psychological and social factors that predispose, precipitate and/or perpetuate brain-gut axis disorders are accounted in psychosomatic and neuroscience literature[1]. Common complaints that often determine visits to pediatric practices are feeding and eating symptoms and elimination problems in infants and toddlers, such as: regurgitation, nausea, vomiting, heartburn, abdominal pain and bellyaches, abdominal distension, bloating, belching, chronic diarrhea or constipation, fecal soiling, retching, or food refusal. Most of them lack biological ground to guide the recovery process.

Gastrointestinal (GI) disorders in childhood are major reasons that drive caregivers to consult healthcare settings[2-5]. As such, functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGID) stand as a group of conditions that include a mixture of age-dependent, chronic or recurrent symptoms without evident structural or biochemical abnormalities affecting GI functioning. Recent report of Kids’ Inpatient Sample Database on hospitalization and cost has indicated the increasing burden of childhood FGID in the United States from 1997 to 2009[6]. Abdominal pain and constipation in childhood were the most common discharge diagnoses. However, good quality epidemiological data on FGID in infants and toddlers to guide the reorganization of pediatric practice are scant.

Many pediatric caregivers lead to misuse primary care and GI specialized care, driving to unnecessary investigations and pharmacological treatments. While several GI symptoms without obvious causal explanation are distressing for small children and their caregivers, these burdensome conditions are not life threatening when parental concerns are properly addressed. Therefore, accurate estimates of prevalence and consequences in agreed description of GI syndromes are required for defining the need for treatment in overloaded healthcare settings.

Purposing public health policy and resource provision, epidemiological studies might show similar frequency for common GI conditions across countries in varied levels of development. Projected proportion of pediatric FGID cases in the community, and different levels of healthcare setting, would help a better allocation of financial support and organize health service delivery.

The aim of this literature review is to critically examine current evidence of knowledge on FGID in infants and toddlers, through systematic search of prevalence data on common functional GI problems.

A literature search was conducted in following databases: PubMed, EMBASE, and Scopus in accordance with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)[7]. The search terms were “functional gastrointestinal disorder” OR “functional gastrointestinal symptoms” AND “epidemiology” OR “prevalence” OR “incidence”. In addition, for each seven specific category of FGID in infants and toddlers, new search was performed with the disorder’s nomenclature and equivalent synonyms. For example, “infant regurgitation” AND “gastroesophageal reflux” were combined with epidemiological terms (Appendix in the Supplementary materials).

There was no language restriction and the period covered was from inception to February 22, 2016. For inclusion, each study had to report epidemiological data on children up to 4 years old and contain standardized outcome criteria (Rome II or III)[8,9]. Case report, letter, editorial, intervention studies, case-control studies, treatment guidelines, review, and duplicate articles were eliminated. “Similar articles” option and manual search of reference list of review articles, book chapter, and gray literature completed the investigation. Experts in pediatric gastroenterology were contacted to request full text or unpublished data. Two reviewers (Ferreira-Maia AP, Wang YP) assessed each study for inclusion and extracted data. Discrepancies were reconciled through discussion.

Afterward data extraction from studies included in qualitative synthesis, a review summarized main epidemiological findings in two broad sections to cover main Rome foundation’s categories (Table 1): (1) feeding and eating disorders; and (2) colic and defecation problems.

| Rome III nomenclature | Age | Frequency | Duration | Synonym or approximate terms | |

| G1 | Infant regurgitation | 3 wk-12 mo | ≥ 2 regurgitations/d | ≥ 3 wk | Gastroesophageal reflux |

| G2 | Infant rumination syndrome | 3-8 mo1 | ≥ 3 mo | Childhood feeding and eating disorders2 | |

| G3 | Cyclic vomiting syndrome | ≥ 2 vomiting episodes | hours - days | Periodic vomiting | |

| G4 | Infant colic | 0-4 mo | ≥ 3 d/wk for ≥ 1 wk | ≥ 3 h/d | Infantile colic; abdominal pain syndrome |

| Wessel’s criteria: irritability, fussing or crying | |||||

| G5 | Functional diarrhea | 6-36 mo1 | ≥ 3 painless stools/d | ≥ 4 wk | Infantile diarrhea |

| G6 | Infant dyschezia | < 6 mo | ≥ 10 min straining | Straining and crying | |

| G7 | Functional constipation | ≤ 4 yr | ≤ 2 defecations/wk | ≥ 4 wk | Classic Iowa criteria |

| ≥ 1 incontinence/wk | Functional defecation disorder | ||||

| Functional fecal retention3 |

Major measurement instruments for assessment of FGID, such as Questionnaire on Pediatric Gastrointestinal Symptoms (QPGS)[10,11] and Pediatric Quality of Life (PedsQL) Inventory[12] were discussed.

The overall quality of included epidemiological studies was evaluated in accordance to Loney’s proposal for prevalence studies of health literature[13]. All studies were scored on eight criteria: (1) sample size; (2) sampling adequacy; (3) unbiased sampling frame; (4) measures of outcomes; (5) unbiased assessors; (6) response rate with refusals described; (7) prevalence with confidence intervals and by relevant subgroups; and (8) appropriate description of study subjects for the research question. The study receives one point for each criterion met, which possible score ranges from zero to eight. The higher score indicates better study quality.

The sample size criterion was not used to exclude studies. However, we considered an appropriate sample size if it was based on local population estimates or if it was higher than 500. This minimum sample size was calculated to permit outcome assessment using simple random sampling, with a conservative estimate of distinct FGID of 20% in the age bracket of infant and toddler[14], confidence level of 95%, and precision of 1.8%, resulting in a sample of 494 subjects.

Two reviewers (Ferreira-Maia AP and Wang YP) performed the evaluation and final results were discussed one by one.

In evaluating studies of the epidemiology of FGID in infants and toddlers, the following methodological questions must be considered: (1) the case definition and evaluation of FGID conditions; (2) the comparability of FGID assessments across studies; (3) the assessment of FGID prevalence and incidence; and (4) the comparability of FGID data drawn in different settings.

Current diagnoses of FGID are symptom-based criteria defined by a mixture of chronic or recurring GI symptoms with no structural or biochemical explanation. The increasing recognition of FGID has been ascribed to the efforts to operationalize clear-cut categories by Rome foundation (http://www.romecriteria.org/). The accomplishment to legitimize and update knowledge on FGID has subjected scientists and clinicians around the world to classify and appraise the science of GI function and dysfunction. Bringing together extensive consensus debates and field studies, this foundation has included a pediatric committee since 1999[15]. Nonetheless, the classification of FGID in infants and toddlers remains largely unexplored and poorly understood.

For Rome III, published in 2006, a working team committed to discuss the case definition of a FGID occurring in children up to 4 years[16]. Under chapter G, four Rome II criteria remained the same in Rome III - regurgitation, rumination, diarrhea, and dyschezia. By consensus, infant colic (G4) was included in Rome III and broader criteria for cyclic vomiting syndrome (G3) and functional constipation (G7) were amended (Table 1). Some duration and frequency requirements were relaxed.

The infant regurgitation (G1) is a common feeding manifestation in infants below the age of 1 year and the frequent reasons of counseling to general practitioners and pediatricians[16]. Whereas common complaints include overfeeding, air swallow during feeding, crying or coughing, physical exam generally reveals no abnormality or weight gain delay.

The infant rumination (G2) is an uncommon feeding disorder and difficult to differentiate from commoner conditions causing vomiting and weight loss. In general, the symptoms start between 3 and 8 mo of age[16]. In infancy or early childhood, avoidance of food or restricted food intake, can include a wide spectrum of feeding disorder, for example pica, rumination disorder, and other presentations that are listed in International Classification of Disease (ICD)[17] and Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) system[18].

The cyclic vomiting syndrome (CVS; G3) is described as recurrent, stereotypic episodes of severe nausea and vomiting lasting hours to days that are separated by symptom-free intervals[19]. The CVS is most observed in toddlers than infants[20,21]. The attacks can occur at regular intervals or sporadically in typical episodes that begin at the same time of day, commonly during early morning or night. Thereafter, vomiting tends to wane, although complaint of nausea persists until the end of episode. In order to facilitate early recognition and mitigate patient suffering, the working committee of Rome III has modified the number of vomit episodes to two for the diagnosis of CVS, instead of three episodes in Rome II[16].

The infant colic (G4) is a condition that usually prompts parents to seek medical care. Classical Wessel’s

criteria defined fussing or colic as “crying for three hours or more on at least three days in at least three weeks”[22]. Since infants with colic are often referred to pediatric gastroenterologists, the Rome III working group achieved consensus to include infant colic as FGID. “Paroxysms of irritability, fussing or crying lasting three hours per day and occurring three days each week” is the amended symptomatic description of colic[16]. Although this condition improves with time (for most infants, crying and irritability begin to decrease by four months of age), it causes significant parental distress, involving long crying bouts and hard-to-soothe behavior[23].

The functional diarrhea (G5) is defined by daily painless, recurrent passage of three or more unformed and large amount of stools for more than four weeks, and with onset between ages of 6 and 36 mo. The important point is no failure to thrive neither inadequate diet. The child feel unworried about the loose stools, and the symptom remit spontaneously by school age[16].

The infant dyschezia (G6) is categorized by a minimum 10 min of straining and crying before successful passage of soft stools in an otherwise healthy infant under 6 mo of age[16]. When occurring several times daily, these episodes are exhausting for the infant and anxiety provoking for the caregivers. The parents usually seek medical help for their child during the first 2 to 3 mo of life with concerns that their child is constipated. In general, the parents describe a healthy infant who cries for 20 to 30 min, turns red in the face, and screams, seemingly in pain, before defecation takes place[24].

The functional constipation (G7) is one of most common reasons that lead parents to visit gastroenterological services[4,14]. Rome II criteria for functional constipation were modified in Rome III, in terms of symptom duration and frequency: from 12 wk to 1 mo and from ≤ three defecations to ≤ two defecations per week[16]. This change was based on data showing that the longer functional constipation goes unrecognized, the less successful treatment is[25].

Generally, along with frequency and duration of the symptoms for diagnosis of a separate syndrome, the Rome criteria operationalized the age range according to the probable occurrence of functional symptoms. Almost all FGID listed in Rome III use monothetic classification rule, which is definition terms of characteristics are both necessary and sufficient to identify members of that condition. One exception is the functional constipation (G7) that is polythetic rule, applied to minimal number of two out of six defining characteristics, i.e., none of the features has to be found in the category in terms of a set of criteria that are neither necessary nor sufficient. For instance, this prototypical description requires that each case of constipation only must possess certain characteristics, allowing identification of broad varieties of the syndrome.

Most exclusionary requirements of Rome III emphasize the benign nature of the FGID in infants and toddlers, with inter-episodic normal health or no failure in thrive. Hierarchical rules of organic exclusion are not always specified, in order to attain the stringent definition of “functional” disorders, where structural or biochemical abnormalities affecting GI functioning must be ruled out. Since around 5% of colic symptoms[26] and 7.7% of constipation symptoms[27] may be consequence of organic etiology, some heterogeneous conditions may be mislabeled as FGID.

Despite of mounting interest for searching causal explanations and applicability of these criteria in pediatric settings, few epidemiological data have strengthened the face validity and clinical utility of symptom-based Rome III criteria. Lack of sensitivity for constipation in Rome II[25,28] and high restrictiveness for dyschezia in Rome III[24] were claims raised by researchers. While some researchers regard Rome III functional constipation more sensitive than Rome II in population under 18 years[29], its applicability in infants and toddlers remains dubious. Similar low rates of constipation in children fewer than 5 years were reported by a study comparing these two criteria in Thailand[30].

Recent efforts to build a multidimensional strategy for establishing the diagnosis of FGID following the approach of DSM for psychiatric syndromes[18] may provide a more thorough description of GI syndromes. Psychosocial and behavioral aspects of the GI problems should be included in future criteria to supplement the complexity of childhood FGID. Although the successive editions of DSM may serve as roadmap to construct more robust categories of FGID, available studies using reliable Rome III criteria have insufficient data to move forward. Large and well-designed epidemiological studies with unbiased sampling are required to document all aspects of natural history of FGID, such as clinical manifestations, pattern of comorbidity, impairment, disability, service use, laboratory study and exclusion of organic disorders, parent-child interaction, family study of genetic aspects, and therapeutic response to different types of intervention. Systematic assessments with validated standardized inventories or structured interviews can improve the nosological validity of FGID in childhood.

Subjective appraisals of GI symptoms through parental reports are unavoidable in small children, because complaints that occur among infants and toddlers depend largely on observation of their caregivers, as well as the decision to set medical appointment. As such, the tendency for FGID to cluster within families was highlighted in previous researches[3,5]. Potential psychosocial mechanisms that may contribute to the intergenerational transmission of illness behaviors were case-control tested in mothers of irritable bowel syndrome children[31]. Parental reinforcement or modeling of symptoms, coping, psychological distress, and exposure to stress were adult responses to child symptoms that might influence the reporting of children’s GI and non-GI symptoms[32].

The implications of inheritance or social learning in the family of FGID are unclear[33]. Studies in children aged 4 or more years have demonstrated that the parent-child concordance was largely poor[11]. In addition, the increased frequency of psychopathology in parents who reported data for their children and overlap with FGID should emerge as potential threat to information bias[3,34].

The QPGS was originally proposed as both a parent report and child self-report for the assessment of child and adolescent GI symptoms[10,11]. Recently, the group of University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill has translated the Rome III FGID diagnostic criteria for infant and toddler into a symptomatic questionnaire (QPGS-RIII) to be answered by their parents or guardians, showing satisfactory face and content validity[34]. For instance, this tool was tested among 332 respondents under 4 years who attended a gastroenterology clinic and agreement between parent and physician was poor to acceptable (κ = 0.18-0.76).

Infant rumination and functional diarrhea were the two categories with poor overlap between parents and physicians. Since over half of new pediatric GI clinic patients met Rome III criteria for one or more FGID[4], a standardized questionnaire with high specificity that satisfy explicit criteria may enhance diagnosis before specialized gastroenterological care appointment.

The impact of pediatric diseases and treatments is increasingly assessed from the perspective of quality of life. In accordance with World Health Organization, health-related quality of life should measure dimensions of physical, emotional (including psychological and cognitive), social, and school/day care functioning. Either pediatric patients or their parents should be asked to report validated measure of quality of life. The Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL; http://www.pedsql.org/) 4.0 Generic Core Scales has been used to assess children with several health conditions, as well as healthy populations[35,36]. The respondents who met Rome’s criteria for FGID presented worse quality of life and more likely have used health care service[5]. Recently, the PedsQL4.0 has been intensively used to investigate FGID[35-38]. The development of the PedsQL GI symptoms was reported[39] and examined in cross-cultural settings[40]. Psychometric properties and construct validity for its applicability in infants up to 24 mo have been accepted[41].

Great variation of prevalence rates can be attributable to sampling methods and population frame. Many of studies on FGID have selected children of different or large age range, from early childhood to late adolescence, hampering comparisons between similar FGID occurring below 4 years. Recruitment methods and settings were varied, but most investigations used data on consecutive treatment-seeking samples in tertiary care, threatening the validity of estimates due to selection bias of hospital-based data[4]. Representativeness of recruited sample and comparability of estimated prevalences are issues of upmost concern. Prospective assessment for organic exclusion was not always reported in studies.

A study to determine the incidence of functional diseases must have a prospective or longitudinal design, and should include children known not to have the disease, who may be observed over an appropriate time period. This type of study is onerous and long time consuming, demanding intense planning and large number of trained researchers. Only two incidence studies were identified for FGID[42,43], their data were drawn from Irish Pediatric Surveillance Unit for CVS in Ireland and Danish National Patient Registry for eating disorders in Denmark. Respectively, case definition has used criteria from the First International Symposium on CVS and the ICD-10 classification[17] of childhood feeding and eating disorders (F98.2 and F50.8).

After recognizing the scarcity of epidemiological data, a recent worldwide Delphi consensus study was conducted to gather data from pediatric workers and scientists to achieve a convergent expert opinion on real-world magnitude of FGID in infants less than 12 mo[14]. In general, the expert panel agreed that good quality data in pediatric gastroenterology were lacking, but the most common FGID in this age range were regurgitation, colic, and constipation, with expected prevalence around 30%, 20%, and 15%, respectively. Functional diarrhea and dyschezia were under-investigated conditions and the likely prevalence was estimated as around 5% for both FGID.

The appropriateness of study design and sampling method for the research question is crucial to determine prevalence of a particular health outcome. An observational study (survey) is the appropriate study design to determine the prevalence of a target condition, by covering the whole population of interest. When the specific population is small, e.g., single pediatric service or private practice, some studies survey the whole population and cannot generalize the results to other populations. Notably, potential selection bias may emerge in accordance with the level of health care specialization, producing overestimated proportion of GI diseases[4,28]. Characteristics of children attending well-baby clinics, immunization center and primary care may differ greatly from the population who visit pediatric gastroenterologist or are referred to a tertiary care for further investigation. In addition to presence of real distressing FGID, this differential probability of service contact depends of caregiver’s own characteristics (e.g., previous history of GI disorders) and socio-economic features, as well as the availability of healthcare services. Taking all bias into account, the comparability of frequency of health outcome diagnosed in different levels of pediatric practice should be avoided.

Since service use sample was referred from lower level of pediatric healthcare, the prevalence rates were likely higher than the sample recruited from community. The appropriate type of sampling frame or list for study recruitment from which subjects are selected is critical for the sample representativeness. Studies of whole, narrowly defined communities are usually done as door-to-door surveys, but this limits the generalizability of the findings outside that community. In large surveys, groups of individuals (e.g., families or children living in defined geographical areas) are selected as the survey units.

Census data can provide data sets from which one can draw a sample that is deemed to have minimal bias, since specific groups of persons are not excluded as they might be in a healthcare service, Internet use or telephone list[4,5,28,44]. When it is not possible to cover the total population, the best sampling technique is probability (simple random) sampling of persons from a defined subset of the population.

In some instances, stratification may be necessary to correctly represent subgroups, in order to ensure representativeness of the population and validate the generalizability of the results for the entire population. For example, exclusive school lists may underrepresent the institutionalized children (hospital, orphanage, correctional communities) or those who are homeless. In relation to the aim of reviewing FGID prevalence studies, the “convenience” sample could be importantly biased in the way that sizable proportion of children with FGID could be missed (because the “cases” of diseases were hospitalized or in home), thus reducing the prevalence of GI diseases in the sample. Population-based surveys offer superior epidemiological data than studies that have recruited children from community, school, well-baby clinic, primary care or specialty care.

The search flow diagram is displayed in Figure 1. It was identified a total of 101 articles through the three databases and two through the manual search. Of these, after removing duplicate records and reading the title and abstract, a total of 28 articles fulfilled the eligibility criteria. After reading the full articles, 13 of them were included in the present review. The 15 studies excluded were listed in the Supplementary materials (Appendix).

Regarding to 13 included articles, 12 studies were written in English and one in Chinese, and published between 2004 and 2015. Eight articles (61.5%) were performed in Europe (Italy, the Netherlands and Turkey), three (23.1%) in America (United States and Brazil) and two (15.4%) in Asia (China and Thailand).

The total sample size varied between 45 and 9660 subjects. In cross-sectional studies, the sample size ranged from 264 to 5030 participants[3,5] among community dweller or attenders of primary care level (e.g., well-baby clinic, immunization center). In Italian formal primary care service, the surveyed population ranged from 2642 to 9660 children[45-47], all enrolled in National Health Service. No routine indication of loss or exclusion was reported in treatment seeking or referred sample to specialty gastroenterological clinic, and the number of participants ranged between 45 and 402[4,44].

Cross-sectional frequency was reported in majority of studies (k = 9), although several investigations followed the recruited sample to confirm diagnosis or organic exclusion. Only four studies prospectively followed infants and toddlers for describing the change of prevalence rate of target GI syndrome at different ages.

Most investigations were conducted with questionable sampling frame, in specialty gastroenterological clinic or university-based hospital (k = 4), primary care (k = 3) or well-baby clinic (k = 2). Further studies in community (k = 4), two of them reported data with debatable methodology (e.g., quota sampling, online panel, non-random recruitment), and only two studies were population-based prospective cohorts[48,49] and provided generalizable data of prevalence of functional constipation, respectively in Brazil and the Netherlands.

Independent assessors applied the Rome foundation’s criteria, either version II or III. Two studies[24,48] modified the Rome criteria and one study[30] compared the two versions.

No age, sex, or race differences were found in FGID diagnoses. 27.1% to 38.0% of infants and toddlers have met any of Rome’s criteria for GI syndromes[3,5], of those 20.8% presented two or more FGID[5]. In pediatric specialty gastroenterological care, FGID was confirmed in 52% of treatment-seeking subjects under to 4 years, around 18% of them presented two or more FGID[4]. In comparison with those who did not meet Rome criteria, subjects with FGID had lower quality of life, delayed thrive, increased medical visits, mental health visits, and hospital stays[3,5].

The critical appraisal of 13 included studies indicated that good quality researches reporting main categories of FGID in infants and toddlers were scarce. Only five articles obtained scores seven or six according to Loney’s proposal[3,24,30,48,49]. The most common quality problem was prevalence rates without confidence interval and/or no detail by subgroup (k = 12), inadequate sampling method (k = 9), inappropriate sampling frame (k = 8), refusers not described (k = 7) and/or insufficient sample size (k = 5) (Supplementary Table 1).

Below, we discussed main epidemiological investigations associated to feeding and eating problems (Table 2), and colic and elimination problems (Table 3).

| Author, year, country | Study design, setting | Sample size (participation %) | Age bracket | Case definition | Case ascertainment | Score | FGID prevalence % | ||

| Regurgitation | Rumination | Cyclic vomiting | |||||||

| Van Tilburg, 2015, United States | Cross-sectional, community | 264 (82.5) | 0-3 yr | Rome III | Online panel w/mothers | 2 | 25.9 | 4.3 | 3.4 |

| QPGS-RIII | |||||||||

| PedsQL4.0 | |||||||||

| Rouster, 2015, United States | Cross-sectional, specialty care | 332 (91.0) | 0-4 yr | Rome III | Parental interviews | 4 | 13.2 | 3.0 | 10.2 |

| QPGS-RIII | |||||||||

| Liu, 2009, China | Cross-sectional, community | 5030 (99.4) | 0-2 yr | Rome III | Parental interviews | 6 | 17.9 | ||

| Parental questionnaire on GI symptoms | |||||||||

| Primavera, 2009, Italy | Cross-sectional, primary care | 9291 (NR) | 0-14 yr | Rome II | Interviews w/parents and children | 4 | 0.44 | ||

| FGID questionnaire | |||||||||

| Campanozzi, 2009, Italy | Cross-sectional, primary care | 2642 (NR) | 1-12 mo | Rome II | Interviews w/parents and children | 4 | 12.0 | ||

| I-GERQ | |||||||||

| Miele, 2004, Italy | Cross-sectional, primary care | 9660 (NR) | 1-12 mo | Rome II | Interviews w/parents and children | 4 | 0.74 | ||

| FGID questionnaires | |||||||||

| Author, year, country | Study design, setting | Sample size (participation %) | Age bracket | Case definition | Case ascertainment | Score | FGID prevalence % | |||

| Colic | Diarrhea | Dyschezia | Constipation | |||||||

| Tharner, 2015, the Netherlands | Population-based birth-cohort, community | 4823 (61) | 2-4 yr | Rome II | Interviews w/parents and children, CEBQ - parental | 7 | 2 yr: 11.2 | |||

| 3 yr: 15.7 | ||||||||||

| 4 yr: 14.2 | ||||||||||

| Van Tilburg, 2015, United States | Cross-sectional, community | 264 (82) | 0-3 yr | Rome III | Online panel w/mothers | 2 | 5.9 | 8.8 | 2.4 | 14.1 |

| QPGS-RIII | ||||||||||

| PedsQL4.0 | ||||||||||

| Kramer, 2015, the Netherlands | Prospective cohort, well-baby clinics | 1292 (87) | 1-9 mo | Rome III | Interviews w/parents and children Parental questionnaire | 6 | 1 mo: 3.9/17.31 | |||

| M-Rome III | 3 mo: 0.9/6.51 | |||||||||

| Rouster, 2015, United States | Cross-sectional, specialty care | 332 (91) | 0–4 yr | Rome III | Parental interviews | 4 | 4.2 | 0.3 | 3.3 | 29.2 |

| QPGS-RIII | ||||||||||

| Osakatul, 2014, Thailand | Cross-sectional, hospital’s catchment area | 3010 (97.1) | 4 mo-5 yr | Rome II | Parental interviews | 7 | 1.9 (Rome II) | |||

| Rome III | Laboratory exams | 1.6 (Rome III) | ||||||||

| Turco, 2014, Italy | Prospective birth-cohort, university-based hospitals | 402 (86.4) | 0-12 mo | Rome III | Telephone interview w/parents | 4 | 3 mo: 11.6 | |||

| 6 mo: 13.7 | ||||||||||

| 12 mo: 10.7 | ||||||||||

| Mota, 2012, Brazil | Population-based birth-cohort, community | 3799 (92) | 0-4 yr | M-Rome II | Interviews w/mothers | 7 | 2 yr: 27.31 | |||

| 4 yr: 31.01 | ||||||||||

| Liu, 2009, China | Cross-sectional, community | 5030 (99.4) | 0-2 yr | Rome III | Parental interviews | 6 | 1.4 | 12.3 | 13.7 | |

| Parental questionnaire on GI symptoms | ||||||||||

| Aydoğdu, 2009, Turkey | Cross-sectional (retrospective), university-based hospital and specialty care unit | 193 (NR) | 0-5 yr | Rome II | Medical records | 3 | 51.9 | |||

| Iowa criteria | Laboratory exams | |||||||||

| Miele, 2004, Italy | Cross-sectional, primary care | 9660 (NR) | 1-12 mo | Rome II | Interviews w/parents and children | 4 | 0.07 | 0.68 | ||

| FGID questionnaires | ||||||||||

| Voskuijl, 2004, the Netherlands | Cross-sectional, tertiary care | 45 (65.7) | ≤ 6 yr | Rome II | Patient diary | 3 | 64.0 | |||

| Iowa criteria | Medical interviews w/ parents and children | |||||||||

| Physical examination | ||||||||||

In total, there were six studies on feeding and eating problems. All of them used questionnaire on FGID to assess the symptoms and half of them were performed in Italy[45-47].

All studies had information about infant regurgitation. The rates ranged from less than 1% in primary care[45,47] to over 25% by online panel in community[5]. Further rate of 13.2% was described in specialty care in United States[4] and 17.9% in Chinese community[3].

Only two studies reported frequency of infant rumination, both from United States, as 4.3% by online panel in community[5] and 3% in specialty care[4].

Based on Rome III, a rate of online parental report of 3.4% was estimated for cyclic vomiting syndrome among children between 1 and 3 years[5] and 10.2% for children under 4 years in a single tertiary care[4], both studies from United States.

Eleven studies described data about colic and defecation problems. Six of them used questionnaire on FGID to assess the symptoms. Three studies were conducted in the Netherlands; two in Italy; two in United States; and the remaining from Thailand, Turkey, China and Brazil.

Three studies had information about frequency of infant colic in children between zero and 4 years. One study reported 4.2% in a specialty care[4], and the others reported 5.9%[5] and 1.4%[3], both carried out in community sample.

The overall rates of functional diarrhea across four studies ranged from 0.07% in primary care[45] to 12.3% in community[3]. The only that used Rome II criteria was also the one with the lowest rate (0.07%).

Concerning to frequency of infant dyschezia through three studies: two cross-sectional studies, with children aged until 4, reported frequency of 2.4% in community[5] and 3.3% in specialty care[4]; one prospective cohort study in well-baby clinics, with children between 1 and 9 mo of age, reported rates 3.9% (Rome III) and 17.3% [Modified-Rome III (M-Rome III)] at age of 1 mo, and 0.9% (Rome III) and 6.5% (M-Rome III) at age of 3 mo[24].

Ten studies reported data about infant constipation. To definition of cases: four articles used Rome III criteria; other four Rome II; one M-Rome II; and one study compared Rome II and Rome III.

For those articles that used Rome III criteria, the frequency of constipation varied between 11.6% at age of 3 mo in a healthy newborns sample[44] to 29.2% in children under 4 years from a specialty care[4].

Rates from 64% in children below 6 years from a tertiary care[28] to 0.68% in infants aged less than 12 mo from a primary care[45] were reported through the studies that used Rome II criteria.

There was only one population-based birth-cohort study[49] that used Rome II criteria; it reported prevalence rates of 11.2%, 15.7% and 14.2% at age of 2, 3 and 4 years respectively.

The Brazilian population-based birth-cohort study[48] used M-Rome II criteria and described prevalence rates of 27.3% at age of 2 years and 31% at age of 4 years.

The last study[30], reported frequencies of 1.9% and 1.6%, respectively for Rome II and III criteria in children under 5 years.

This review, relied on data from 13 articles, showed a vast variation in the FGID prevalence in infants and toddlers. The majority of studies (k = 7) recruited participants from primary care or specialty care. Further studies were 4 cross-sectional ones in community and 2 in well-baby clinics. Good quality epidemiological data reporting main categories of FGID in infants and toddlers were limited. Based on current review, it is suggested that there is an increasing burden attributed to FGID in pediatric practices. However, generalizable information is restricted in terms of community studies and well-assessed diagnosis that might support observed differences across pediatric care levels.

Infant regurgitation and functional constipation are the most investigated disorders in FGID and might have public health impact.

More conclusive recommendation should be avoided as the rates vary greatly across studies. Although the broad variation in the infant regurgitation prevalence may reflect the poor quality of epidemiological data (recruitment and sampling frame), expert respondents to a recent consensus survey according to Rome III criteria reported an average worldwide prevalence of 29%[14]. This rate is similar to the rate reported in the included study with a community sample. For instance, three surveys from Italy used the National Health Service registry in different regions of the country and reported frequencies as low as less than 1% to 12% of children in primary care.

As a pathology liable to affect all ages, most of included studies provided data on functional constipation. The Dutch Generation R study and the Brazilian study investigated the entire pediatric population and provided unbiased information on functional constipation of higher external validity. The first study reported prevalence similar to that estimated by experts (around 15%)[14], but the second study described a two times larger prevalence. This finding might be due the use of modified Rome II, with broader criteria.

The colic symptom is common and leads one in six families (17%) with children to seek a health professional[50], although there was a wide variation in the frequency of functional infant colic in community and specialty setting, highlighting the necessity of studies with rigorous design and diagnostic criteria to promote a adequate prevalence.

The true prevalence related to infant rumination, CVS, diarrhea and dyschezia remains changeable and uncertain. In view of scarce data on these FGID, it is hard to know how they develop in infants and toddlers. Therefore, better training of pediatricians and investigators and clearer descriptions of disorders may refine clinical utility and endorse research of Rome III category.

The lack of well-conducted studies has imposed us to compare existing studies that have consistently used reliable criteria for functional disorders. Therefore, the epidemiological knowledge on FGID in infants and toddlers still has to resort to few surveys that have ensured the reproducibility of case definition. In this direction, summary meta-analysis is not performed due to insufficient studies conducted with similar methodology.

The observed heterogeneity of frequency rates is likely beyond those features attributable to chance. The difference has arisen because of clinical dissimilarities between studies (for example, setting, types and age of participants, respondents or assessors) or methodological differences (such as diagnostic criteria, assessment tool, sampling frame). Our qualitative appraisal revealed that most included studies were of moderate or below average standard of generalizability. Notwithstanding, non-eligible articles (without data on FGID, non-reliable Rome criteria, non-specific data to infants and toddlers) were excluded to avoid spuriously inflated frequencies of FGID.

Reporting bias in cross-sectional data is most related to delay in publication (file drawer bias) and selective language bias. However, we have actively contacted experts to inquire on non-published data (such as poster presentation, conference paper, local journals) and non-English surveys. We were able to get access to one additional study not covered in initial search[48] and another non-English study[3]. In summary, it is judicious to state that the abovementioned heterogeneity must be more related to the quality of existing investigations than to publication bias.

The authors thank Alexandre Canon Boronat, MD, for the linguistic revision of the manuscript.

Unremitting gastrointestinal symptoms wane and wax in a significant proportion of infants younger than 48 mo. The pathophysiology of the functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGID) remains unclear, but likely involves a complex interplay of autonomic, psychosocial, dietary, microbial, and gastric sensorimotor disturbances. FGID in infants and toddlers seem to be related to an increasing healthcare burden, though, valid epidemiological data are scarce. The aim of this review is to examine current evidence of knowledge on FGID in infants and toddlers, through systematic search of prevalence data on common functional GI problems.

Until nowadays, there is no laboratorial test for diagnoses of FGID and clinicians must rely on the patients’ symptoms for identification of the clinical pictures. In the case of infants and toddlers, careful assessment to establish threshold of the parental/caregiver report is required. The validity of explicit diagnostic criteria and reliability of psychometric tools is still limited. Strategies to avoid excessive hospitalizations and unnecessary investigative testing are needed. While global recognition and legitimization of FGID can expand the pathophysiological understanding of brain-gut axis dysfunction to further optimize clinical management for these patients, adequate epidemiological studies - with reliable and valid case definition, appropriate design, sufficient sample size, correct sampling, and data collection - can shed light from the black box of FGID in infants and toddlers.

FGID in infants and toddlers seem to be common in pediatric outpatient and inpatient practice, mainly infant regurgitation and functional constipation. Conversely, few population-based studies on epidemiology issue were conducted so far, and, good quality epidemiological data to support diagnostic criteria are lacking. The update of Rome criteria (Rome IV) is launched in 2016, but few reformulations for FGID in infants and toddlers are made. Nevertheless, the important advantage of this new version is to merge scientific investigation and clinical practice to improve the diagnostic classification system. For this purpose, predefined fields of interest have been created since 2013 such as gut microflora, the role of food and diet, the nature of severity for FGID, the development and validation of Rome IV questionnaire, the management of FGID in primary care setting and the multi-dimensional clinical profile.

This review highlights future directions for research: (1) well-designed epidemiological studies should be conducted in different levels of pediatric practice, in terms of sample recruitment, representativeness, sample size, and clinical assessment; (2) a new classification system of early childhood FGID must be simple, easy to understand (especially by primary care physicians and nurses), and must include age-dependent gastroenterological features recognizable by parents; (3) research agenda of comprehensive studies on course and associated disability of FGID should be set to refine its definition and classification; and (4) multidimensional approach can improve the current symptom-based classification of Rome criteria.

FGID comprise chronic or recurrent symptoms that arise in the absence of anatomic abnormality, inflammation, or tissue damage. The symptoms are variable and age-dependent.

In this systematic review, the authors have presented a carefully designed study on the epidemiology of FGID in infants and toddlers. Based on the overall data the authors indicated future directions in the field of epidemiological studies concerning FGID.

Manuscript Source: Invited manuscript

Specialty Type: Gastroenterology and Hepatology

Country of Origin: Brazil

Peer-Review Report Classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Mulak A, Pearson JS S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: A E- Editor: Ma S

| 1. | Van Oudenhove L, Vandenberghe J, Demyttenaere K, Tack J. Psychosocial factors, psychiatric illness and functional gastrointestinal disorders: a historical perspective. Digestion. 2010;82:201-210. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 48] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Infante Pina D, Badia Llach X, Ariño-Armengol B, Villegas Iglesias V. Prevalence and dietetic management of mild gastrointestinal disorders in milk-fed infants. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:248-254. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 21] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 23] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Liu W, Xiao LP, Li Y, Wang XQ, Xu CD. [Epidemiology of mild gastrointestinal disorders among infants and young children in Shanghai area]. Zhonghua Er Ke Zazhi. 2009;47:917-921. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Rouster AS, Karpinski AC, Silver D, Monagas J, Hyman PE. Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders Dominate Pediatric Gastroenterology Outpatient Practice. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2016;62:847-851. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 64] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | van Tilburg MA, Hyman PE, Walker L, Rouster A, Palsson OS, Kim SM, Whitehead WE. Prevalence of functional gastrointestinal disorders in infants and toddlers. J Pediatr. 2015;166:684-689. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 93] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Park R, Mikami S, LeClair J, Bollom A, Lembo C, Sethi S, Lembo A, Jones M, Cheng V, Friedlander E. Inpatient burden of childhood functional GI disorders in the USA: an analysis of national trends in the USA from 1997 to 2009. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;27:684-692. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 66] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 47017] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 43210] [Article Influence: 2880.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Rasquin-Weber A, Hyman PE, Cucchiara S, Fleisher DR, Hyams JS, Milla PJ, Staiano A. Childhood functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gut. 1999;45 Suppl 2:II60-II68. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 279] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 323] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Rasquin A, Di Lorenzo C, Forbes D, Guiraldes E, Hyams JS, Staiano A, Walker LS. Childhood functional gastrointestinal disorders: child/adolescent. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1527-1537. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1150] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1046] [Article Influence: 58.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 10. | Caplan A, Walker L, Rasquin A. Development and preliminary validation of the questionnaire on pediatric gastrointestinal symptoms to assess functional gastrointestinal disorders in children and adolescents. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2005;41:296-304. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 89] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Caplan A, Walker L, Rasquin A. Validation of the pediatric Rome II criteria for functional gastrointestinal disorders using the questionnaire on pediatric gastrointestinal symptoms. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2005;41:305-316. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 93] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Varni JW, Seid M, Knight TS, Uzark K, Szer IS. The PedsQL 4.0 Generic Core Scales: sensitivity, responsiveness, and impact on clinical decision-making. J Behav Med. 2002;25:175-193. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 401] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 433] [Article Influence: 19.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Loney PL, Chambers LW, Bennett KJ, Roberts JG, Stratford PW. Critical appraisal of the health research literature: prevalence or incidence of a health problem. Chronic Dis Can. 1998;19:170-176. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 14. | Vandenplas Y, Abkari A, Bellaiche M, Benninga M, Chouraqui JP, Çokura F, Harb T, Hegar B, Lifschitz C, Ludwig T. Prevalence and Health Outcomes of Functional Gastrointestinal Symptoms in Infants From Birth to 12 Months of Age. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2015;61:531-537. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 125] [Article Influence: 13.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Drossman DA. The functional gastrointestinal disorders and the Rome III process. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1377-1390. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1467] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1420] [Article Influence: 78.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Hyman PE, Milla PJ, Benninga MA, Davidson GP, Fleisher DF, Taminiau J. Childhood functional gastrointestinal disorders: neonate/toddler. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1519-1526. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 389] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 317] [Article Influence: 17.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | World Health Organization. The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders: clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization 1992; . [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 18. | American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®). : American Psychiatric Pub 2013; . [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 19. | Li BU, Issenman RM, Sarna SK. Consensus statement--2nd International Scientific Symposium on CVS. The Faculty of The 2nd International Scientific Symposium on Cyclic Vomiting Syndrome. Dig Dis Sci. 1999;44:9S-11S. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 20. | Fleisher DR. The cyclic vomiting syndrome described. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1995;21 Suppl 1:S1-S5. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 29] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Fleisher DR, Matar M. The cyclic vomiting syndrome: a report of 71 cases and literature review. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1993;17:361-369. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 90] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Wessel MA, Cobb JC, Jackson EB, Harris GS, Detwiler AC. Paroxysmal fussing in infancy, sometimes called colic. Pediatrics. 1954;14:421-435. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 23. | Wake M, Morton-Allen E, Poulakis Z, Hiscock H, Gallagher S, Oberklaid F. Prevalence, stability, and outcomes of cry-fuss and sleep problems in the first 2 years of life: prospective community-based study. Pediatrics. 2006;117:836-842. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 216] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 190] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Kramer EA, den Hertog-Kuijl JH, van den Broek LM, van Leengoed E, Bulk AM, Kneepkens CM, Benninga MA. Defecation patterns in infants: a prospective cohort study. Arch Dis Child. 2015;100:533-536. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 20] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Loening-Baucke V. Functional fecal retention with encopresis in childhood. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2004;38:79-84. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 48] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Freedman SB, Al-Harthy N, Thull-Freedman J. The crying infant: diagnostic testing and frequency of serious underlying disease. Pediatrics. 2009;123:841-848. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 87] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Aydoğdu S, Cakir M, Yüksekkaya HA, Arikan C, Tümgör G, Baran M, Yağci RV. Chronic constipation in Turkish children: clinical findings and applicability of classification criteria. Turk J Pediatr. 2009;51:146-153. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 28. | Voskuijl WP, Heijmans J, Heijmans HS, Taminiau JA, Benninga MA. Use of Rome II criteria in childhood defecation disorders: applicability in clinical and research practice. J Pediatr. 2004;145:213-217. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 90] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Burgers R, Levin AD, Di Lorenzo C, Dijkgraaf MG, Benninga MA. Functional defecation disorders in children: comparing the Rome II with the Rome III criteria. J Pediatr. 2012;161:615-20.e1. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 43] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Osatakul S, Puetpaiboon A. Use of Rome II versus Rome III criteria for diagnosis of functional constipation in young children. Pediatr Int. 2014;56:83-88. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 18] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | van Tilburg MA, Levy RL, Walker LS, Von Korff M, Feld LD, Garner M, Feld AD, Whitehead WE. Psychosocial mechanisms for the transmission of somatic symptoms from parents to children. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:5532-5541. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 48] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 42] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Walker LS, Zeman JL. Parental response to child illness behavior. J Pediatr Psychol. 1992;17:49-71. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 156] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 166] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Buonavolontà R, Coccorullo P, Turco R, Boccia G, Greco L, Staiano A. Familial aggregation in children affected by functional gastrointestinal disorders. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010;50:500-505. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 31] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | van Tilburg MA, Rouster A, Silver D, Pellegrini G, Gao J, Hyman PE. Development and Validation of a Rome III Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders Questionnaire for Infants and Toddlers. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2016;62:384-386. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 20] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Varni JW, Bendo CB, Denham J, Shulman RJ, Self MM, Neigut DA, Nurko S, Patel AS, Franciosi JP, Saps M. PedsQL gastrointestinal symptoms module: feasibility, reliability, and validity. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2014;59:347-355. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 54] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Varni JW, Bendo CB, Denham J, Shulman RJ, Self MM, Neigut DA, Nurko S, Patel AS, Franciosi JP, Saps M. PedsQL™ Gastrointestinal Symptoms Scales and Gastrointestinal Worry Scales in pediatric patients with functional and organic gastrointestinal diseases in comparison to healthy controls. Qual Life Res. 2015;24:363-378. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 39] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Hartman EE, Pawaskar M, Williams V, McLeod L, Dubois D, Benninga MA, Joseph A. Psychometric properties of PedsQL generic core scales for children with functional constipation in the Netherlands. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2014;59:739-747. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 12] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Varni JW, Bendo CB, Shulman RJ, Self MM, Nurko S, Franciosi JP, Saps M, Saeed S, Zacur GM, Vaughan Dark C. Interpretability of the PedsQL™ Gastrointestinal Symptoms Scales and Gastrointestinal Worry Scales in Pediatric Patients With Functional and Organic Gastrointestinal Diseases. J Pediatr Psychol. 2015;40:591-601. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 36] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Varni JW, Kay MT, Limbers CA, Franciosi JP, Pohl JF. PedsQL gastrointestinal symptoms module item development: qualitative methods. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012;54:664-671. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 45] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Buck D. The PedsQL™ as a measure of parent-rated quality of life in healthy UK toddlers: psychometric properties and cross-cultural comparisons. J Child Health Care. 2012;16:331-338. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 11] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Varni JW, Limbers CA, Neighbors K, Schulz K, Lieu JE, Heffer RW, Tuzinkiewicz K, Mangione-Smith R, Zimmerman JJ, Alonso EM. The PedsQL™ Infant Scales: feasibility, internal consistency reliability, and validity in healthy and ill infants. Qual Life Res. 2011;20:45-55. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 150] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 159] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Hvelplund C, Hansen BM, Koch SV, Andersson M, Skovgaard AM. Perinatal Risk Factors for Feeding and Eating Disorders in Children Aged 0 to 3 Years. Pediatrics. 2016;137:e20152575. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 15] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Fitzpatrick E, Bourke B, Drumm B, Rowland M. The incidence of cyclic vomiting syndrome in children: population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:991-995; quiz 996. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 43] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Turco R, Miele E, Russo M, Mastroianni R, Lavorgna A, Paludetto R, Pensabene L, Greco L, Campanozzi A, Borrelli O. Early-life factors associated with pediatric functional constipation. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2014;58:307-312. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 24] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Miele E, Simeone D, Marino A, Greco L, Auricchio R, Novek SJ, Staiano A. Functional gastrointestinal disorders in children: an Italian prospective survey. Pediatrics. 2004;114:73-78. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 140] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Campanozzi A, Boccia G, Pensabene L, Panetta F, Marseglia A, Strisciuglio P, Barbera C, Magazzù G, Pettoello-Mantovani M, Staiano A. Prevalence and natural history of gastroesophageal reflux: pediatric prospective survey. Pediatrics. 2009;123:779-783. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 99] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Primavera G, Amoroso B, Barresi A, Belvedere L, D’Andrea C, Ferrara D, Cascio AL, Rizzari S, Sanfilippo E, Spataro A. Clinical utility of Rome criteria managing functional gastrointestinal disorders in pediatric primary care. Pediatrics. 2010;125:e155-e161. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Mota DM, Barros AJ, Santos I, Matijasevich A. Characteristics of intestinal habits in children younger than 4 years: detecting constipation. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012;55:451-456. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 16] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Tharner A, Jansen PW, Kiefte-de Jong JC, Moll HA, Hofman A, Jaddoe VW, Tiemeier H, Franco OH. Bidirectional associations between fussy eating and functional constipation in preschool children. J Pediatr. 2015;166:91-96. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 42] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Lucassen PL, Assendelft WJ, van Eijk JT, Gubbels JW, Douwes AC, van Geldrop WJ. Systematic review of the occurrence of infantile colic in the community. Arch Dis Child. 2001;84:398-403. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 199] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 174] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |