Published online Aug 28, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i32.9598

Peer-review started: January 30, 2015

First decision: March 10, 2015

Revised: April 16, 2015

Accepted: June 9, 2015

Article in press: June 10, 2015

Published online: August 28, 2015

AIM: To compare the histological outcome of chronic hepatitis B (CHB) patients treated with entecavir (ETV) or lamivudine (LAM)-based therapy.

METHODS: We conducted a retrospective analysis of data from 42 CHB patients with advanced fibrosis (baseline Ishak score ≥ 2) or cirrhosis who were treated with ETV or LAM-based therapy in Beilun People’s Hospital, Ningbo between January 2005 and May 2012. The patients enrolled were more than 16 years of age and underwent a minimum of 12 mo of antiviral therapy. We collected data on the baseline characteristics of each patient and obtained paired liver biopsies pre- and post-treatment. The Knodell scoring system and Ishak fibrosis scores were used to evaluate each example. An improvement or worsening of necroinflammation was defined as ≥ 2-point change in the Knodell inflammatory score. The progression or regression of fibrosis was defined as ≥ 1-point change in the Ishak fibrosis score. The continuous variables were compared using t-test or Mann-Whitney test, and the binary variables were compared using χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test. The results of paired liver biopsies were compared with a Wilcoxon signed rank test.

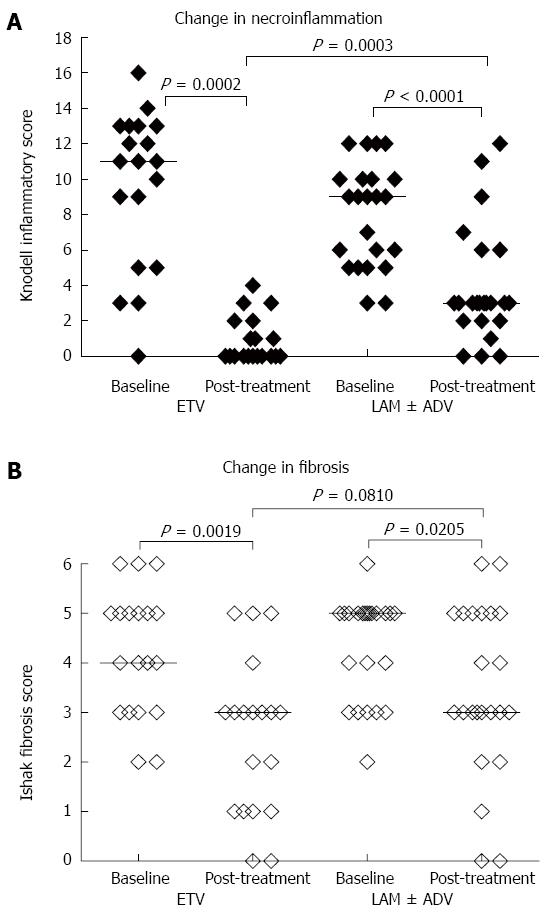

RESULTS: Nineteen patients were treated with ETV and 23 patients were treated with LAM therapy for a mean duration of 39 and 42 mo, respectively. After long-term antiviral treatment, 94.74% (18/19) of the patients in the ETV arm and 95.65% (22/23) in the LAM arm achieved an HBV DNA level less than 1000 IU/mL. The majority of the patients (94.74% in the ETV arm and 73.91% in the LAM arm) had normalized ALT levels. The median Knodell necroinflammatory score decreased from 11 to 0 in the patients receiving ETV, and the median Knodell score decreased from 9 to 3 in the patients receiving LAM (P = 0.0002 and < 0.0001, respectively). The median Ishak fibrosis score showed a 1-point reduction in ETV-treated patients and a 2-point reduction in LAM-treated patients (P = 0.0019 and 0.0205, respectively). The patients receiving ETV showed a more significant improvement in necroinflammation than the LAM-treated patients (P = 0.0003). However, there was no significant difference in fibrotic improvement between the two arms. Furthermore, two patients in each arm achieved a fibrosis score of 0 post-treatment, which indicates a full reversion of fibrosis after antiviral therapy.

CONCLUSION: CHB patients with advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis benefit from antiviral treatment. ETV is superior to LAM therapy in improving necroinflammatory but not fibrotic outcome.

Core tip: This retrospective cohort study compared the histological outcomes of long-term antiviral treatment for an average of more than 3 years with entecavir monotherapy or lamivudine-based combination therapy in chronic hepatitis B patients with significant fibrosis or cirrhosis. There was a histological improvement observed in the majority of patients in both arms. There were also improved virological responses, alanine aminotransferase normalization, and serological responses. Additionally, 4 of 48 patients achieved a full reversion of fibrosis or cirrhosis. Entecavir was superior to lamivudine-based therapy in improving necroinflammatory but not fibrotic outcome.

-

Citation: Wang JL, Du XF, Chen SL, Yu YQ, Wang J, Hu XQ, Shao LY, Chen JZ, Weng XH, Zhang WH. Histological outcome for chronic hepatitis B patients treated with entecavir

vs lamivudine-based therapy. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(32): 9598-9606 - URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i32/9598.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i32.9598

Chronic hepatitis B (CHB) affects approximately 350 million people worldwide and hepatitis B virus (HBV)-related end stage liver diseases are responsible for 1 million deaths annually[1-3]. In China, the prevalence of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) is found in approximately 7% of the general population[4]. Liver fibrosis is one of the common complications of CHB and is a result of sustained viral replication and chronic inflammation. Liver fibrosis may also lead to cirrhosis. Hepatic cirrhosis is the end stage of fibrosis and is characterized by distinguishing histological features such as the formation of regenerative nodules and diffuse fibrosis. Patients with cirrhosis have high mortality and morbidity due to poor liver function and the development of portal hypertension[5]. Another major complication is the development of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)[6]. Thus, effective therapies that prevent the progression of HBV-related liver diseases are urgently needed in clinical practice.

The current therapy regimens available for CHB patients include nucleos(t)ide analogues (NAs) and interferon-α (INF-α). These therapy regimens differ with respect to antiviral mechanism and treatment responses[7,8]. The drugs lamivudine (LAM), adefovir (ADV), telbivudine (LdT), entecavir (ETV) and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) are approved NAs for the treatment of CHB. NA therapy directly inhibits viral replication by targeting HBV DNA polymerases and can achieve rapid viral suppression and normalization of serum transaminases[9]. LAM was the first approved oral antiviral agent and was initially considered the best choice for CHB treatment because of its good potency and safety profile[10,11]. However, the major limitation of LAM is the high rate of virologcial resistance, and ADV add-on is a rescue therapy for LAM resistance[12,13]. The use of LAM has been gradually reduced since the introduction of novel antiviral agents with a higher genetic barrier of resistance such as ETV and TDF. However, LAM is still widely used in developing countries due to its low cost.

Two early global clinical trials found that 48 wk of ETV therapy was superior to LAM in treatment-naïve CHB patients with respect to virological response, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) normalization, and histological improvement[9,10]. However, it is unclear whether patients with advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis benefit more from ETV therapy than LAM therapy. Thus, the aim of this study was to compare the histological outcome of CHB patients with advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis after long-term treatment with ETV or LAM-based therapy.

The patients eligible for this retrospective study were CHB cases with advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis who had received ETV or LAM-based combination therapy (ADV was added when patients had LAM resistance) at the clinic or were hospitalized in Beilun People’s Hospital, Ningbo between January 2005 and May 2012. The inclusion criteria of our study were the following: age ≥ 16 years, HBsAg-positivity for more than 6 mo, a minimum of 12 mo of antiviral therapy with ETV or LAM-based combination therapy (LAM + ADV), adequate pre- and post-treatment biopsy samples, and a diagnosis of advanced fibrosis or compensated cirrhosis at baseline (Ishak score ≥ 2). The patient exclusion criteria included the following: co-infection with hepatitis C virus, hepatitis D virus, or human immunodeficiency virus, hepatic decompensation, or prior exposure to either IFN-α or other NAs including LdT or ADV monotherapy. There were 42 patients enrolled in the current study including 19 in the ETV-treated arm and 23 in the LAM-based combination arm. Paired liver biopsies and clinical data were collected and analyzed from each patient. The study protocol was reviewed by the local ethics committees, and the ethical approval documents were waived. Written informed consent for the liver biopsy was obtained from each participant. This is a retrospective study and all study participants were de-identified. Therefore, informed consent was not obtained prior to study enrollment.

Both the Knodell scoring system (0 to 18) and Ishak fibrosis scores (0 to 6) were used to evaluate the necroinflammatory level and fibrotic extent in the liver biopsy specimens. A pathologist who was blinded to the patient clinical data and the sequences of biopsy samples evaluated the liver histology. An improvement or worsening of necroinflammation was defined as ≥ 2-point change in the Knodell inflammatory score. The progression or regression of fibrosis was defined as ≥ 1-point change in Ishak fibrosis score.

The continuous variables are expressed as mean ± SD and were compared by t-test or Mann-Whitney test. All binary variables were summarized as counts and percentages and were compared by χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test. The results of paired liver biopsies were expressed as the median and were compared by Wilcoxon signed rank test. The statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 19.0. A two-sided P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The statistical methods of this study were reviewed by Xiao-Qin Wang from the Department of Clinical Epidemiology of Huashan Hospital, Fudan University, Shanghai, China.

This retrospective cohort study enrolled 42 CHB patients with advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis. There were 19 cases treated with ETV and 23 cases treated with LAM-based combination therapy for a mean duration of 39 and 42 mo, respectively. The baseline characteristics of the two arms are summarized in Table 1.

| ETV | LAM ± ADV | P-value | |

| n | 19 | 23 | |

| Male gender, n (%) | 14 (73.7) | 16 (69.6) | 0.7687 |

| Age (mean ± SD), yr | 43.2 ± 9.8 | 43.7 ± 9.9 | 0.8721 |

| log10 HBV DNA (mean ± SD), IU/mL | 6.6 ± 1.5 | 6.2 ± 1.4 | 0.4019 |

| ALT (mean ± SD), U/L | 107 ± 84 | 96 ± 112 | 0.2450 |

| HBeAg positive, n (%) | 13 (68.42) | 14 (60.87) | 0.6112 |

| Median grade (range) | 11 (0-16) | 9 (3-12) | 0.0749 |

| Median stage (range) | 4 (2-6) | 5 (2-6) | 0.7381 |

| Duration of treatment (mean ± SD), mo | 39 ± 11 | 42 ± 15 | 0.6951 |

The outcomes of the two arms after long-term therapy are outlined in Table 2. The results include virological, biochemical, and serological responses. The data indicated that 94.74% (18/19) of patients in the ETV arm and 95.65% (22/23) in the LAM arm achieved an HBV DNA level less than 1000 IU/mL after long-term antiviral therapy. Furthermore, 76.92% (10/13) of patients in the ETV arm and 68.75% (11/16) in the LAM arm achieved an HBV DNA level less than 60 IU/mL based on the results of the COBAS AmpliPrep/COBAS TaqMan HBV Test. The majority of patients (94.74% in the ETV arm and 73.91% in the LAM arm) achieved ALT normalization after long-term treatment. However, there were no significant differences between the two arms (P = 0.0715). Hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) loss and seroconversion occurred in 46.15% (6/13) and 38.46% (5/13) of HBeAg positive patients in the ETV arm, respectively. Additionally, 71.43% (10/14) and 42.86% (6/14) of patients in the LAM arm experienced HBeAg loss and seroconversion, respectively. HBsAg loss was not observed in any patient.

| ETV | LAM ± ADV | P-value | |

| n | 19 | 23 | |

| HBV DNA < 1000 IU/mL | 18 (94.74) | 22 (95.65) | 0.8897 |

| HBV DNA < 60 IU/mL | 10/13 (76.92) | 11/16 (68.75) | 0.6243 |

| ALT ≤ 1 × upper limit of normal | 18 (94.74) | 17 (73.91) | 0.0715 |

| HBeAg loss/HBeAg positive at baseline | 6/13 (46.15) | 10/14 (71.43) | 0.1817 |

| HBe seroconversion/HBeAg positivity at baseline | 5/13 (38.46) | 6/14 (42.86) | 0.8163 |

| HBsAg loss | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | - |

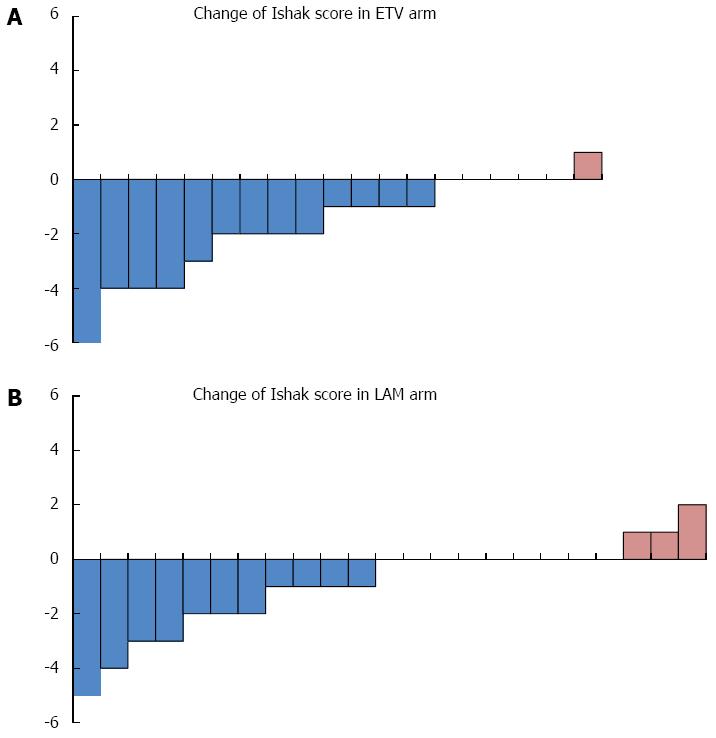

There was a significant improvement of histological outcome observed in both treatment arms compared to baseline (Table 3). The median Knodell necroinflammatory score decreased from 11 to 0 in the ETV arm and from 9 to 3 in the LAM arm (P = 0.0002 and < 0.0001, respectively). The median Ishak fibrosis score showed a 1-point reduction in the ETV arm and a 2-point reduction in the LAM arm (P = 0.0019 and 0.0205, respectively). Eighteen of the 19 patients in the ETV arm showed improvement of necroinflammatory scores. Additionally, 11 patients achieved a score of 0 post-treatment. This result indicates full reversion of the necroinflammatory condition. Furthermore, 68.42% of patients in the ETV arm and 47.83% in the LAM arm showed improvement in fibrosis. The results indicate 26.32% of patients in the ETV arm and 39.13% in the LAM arm remained stable. There was 1 patient from the ETV arm and 3 patients from the LAM arm who had worsening Ishak fibrosis scores.

| ETV (n = 19) | LAM ± ADV (n = 23) | |

| Change in necroinflammation | ||

| Median grade (range) | 11 (0-16)1 to 0 (0-4)1 | 9 (3-12)2 to 3 (0-12)2 |

| Improved | 18 (94.74) | 19 (82.61) |

| No change | 1 (5.26) | 4 (17.39) |

| Worsened | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Change in fibrosis | ||

| Median stage (range) | 4 (2-6)3 to 3 (0-5)3 | 5 (2-6) 4 to 3 (0-6)4 |

| Improved | 13 (68.42) | 11 (47.83) |

| No change | 5 (26.32) | 9 (39.13) |

| Worsened | 1 (5.26) | 3 (13.04) |

There was a significant improvement in necroinflammatory score in the ETV arm compared to the LAM arm after long-term therapy (P = 0.0003) (Figure 1A). However, there was no significant difference in Ishak score improvement observed between the two arms (P = 0.0810) (Figure 1B). There were more patients in the ETV arm who achieved regression and fewer patients suffered Ishak score progression (Figure 2).

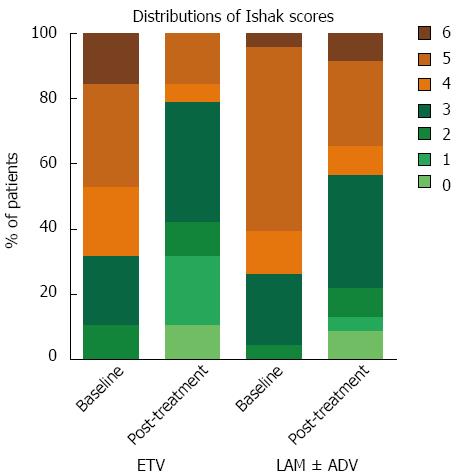

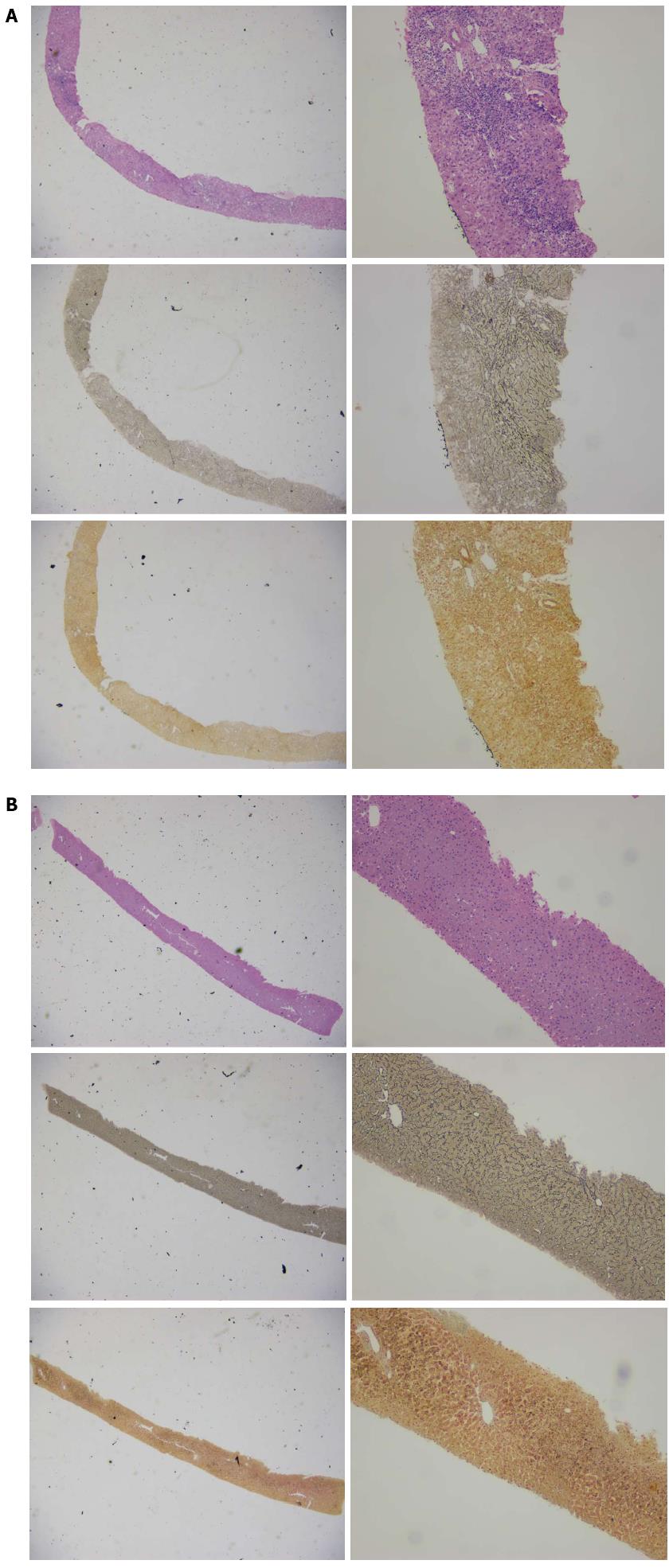

We further analyzed the distribution of the Ishak score pre- and post-treatment in the two arms and found that two patients from each arm had achieved a score of 0, which indicates a full reversion of advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis (Figure 3). The two patients from the ETV arm had baseline Ishak scores of 4 and 6. The scores for both cases decreased to 0 after 44 and 30 mo of ETV monotherapy, respectively. The two patients in the LAM arm had baseline fibrosis scores of 3 and 5. These patients achieved a score of 0 after 43 mo of LAM monotherapy and 47 mo of LAM and ADV combination therapy (ADV was added when LAM resistance emerged), respectively. Figure 4 shows the favorable histological outcome of a 35-year old female patient with a Knodell score of 14 and an Ishak score of 4 at baseline. This patient achieved a score of 0 for both necroinflammatory and fibrotic score after 44 mo of ETV monotherapy.

We further investigated which patients benefited most from long-term NA therapy in fibrotic regression or reversion. The results showed that patients with higher Ishak score at baseline and longer duration of treatment benefit more in fibrotic regression (Table 4). Conversely, patients who experienced significant improvement in fibrosis after long-term NAs therapy had higher HBV DNA and ALT levels at baseline (Table 5).

| With improvement in fibrosis | Without improvement in fibrosis | P-value | |

| n | 24 | 18 | |

| Male gender, n (%) | 17 (70.83) | 13 (72.22) | 0.9215 |

| Age (mean ± SD), yr | 43.8 ± 9.9 | 42.9 ± 9.8 | 0.7596 |

| log10 HBV DNA (mean ± SD), IU/mL | 6.7 ± 1.2 | 5.9 ± 1.5 | 0.0602 |

| ALT (mean ± SD), U/L | 102 ± 82 | 99 ± 121 | 0.6473 |

| HBeAg positivity, n (%) | 17 (70.83) | 10 (55.56) | 0.3065 |

| Median grade (range) | 10 (3-16) | 9 (0-13) | 0.1713 |

| Median stage (range) | 5 (3-6) | 3.5 (2-5) | 0.0230 |

| Treated with ETV, n (%) | 13 (54.17) | 6 (33.33) | 0.1795 |

| Treatment duration ≥ 24 mo, n (%) | 24 (100) | 13 (72.22) | 0.0101 |

| With significant improvement1 | Without improvement | P-value | |

| n | 9 | 18 | |

| Male gender, n (%) | 6 (66.7) | 13 (72.2) | 0.7657 |

| Age (mean ± SD), yr | 42.1 ± 11.6 | 42.9 ± 9.8 | 0.8557 |

| log10 HBV DNA (mean ± SD), IU/mL | 7.3 ± 1.0 | 5.9 ± 1.5 | 0.0175 |

| ALT (mean ± SD), U/L | 140 ± 72 | 99 ± 121 | 0.0270 |

| HBeAg positivity, n (%) | 7 (77.8) | 10 (55.6) | 0.2597 |

| Median grade (range) | 11(3-14) | 9 (0-13) | 0.2778 |

| Median stage (range) | 5 (3-6) | 3.5 (2-5) | 0.2717 |

| Duration of treatment (mean ± SD), mo | 44 ± 11 | 41 ± 18 | 0.3956 |

This was a retrospective study that investigated the efficacy of long-term treatment with two different NAs in CHB patients with advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis. LAM was the first approved NA for treatment of CHB in 1998 and was effective in suppressing HBV DNA, normalizing ALT, and improving histological outcome. However, the use of LAM was limited by the high rate of LAM resistance[14]. It was reported that 5 years of LAM treatment resulted in 70% drug relevant resistance[3,15]. The addition of ADV is one of the rescue therapies for patients who experienced LAM resistance. In 2005, ETV was approved for use in treatment-naïve and LAM-resistant patients at a dose of 0.5 mg/d and 1 mg/d, respectively[16]. In 2006, two global multicenter clinical trials demonstrated that both HBeAg negative and positive patients benefit more from 48 wk of ETV treatment than LAM treatment in virological, biochemical, and histological improvements[17,18]. Moreover, a study in 2008 found a trend of histological improvement after 48 wk of LAM and ETV treatment in patients with advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis was similar[19]. The respective histological improvements after long-term treatment of the two NAs were significant. However, whether ETV is superior to LAM after long-term treatment remains unclear[20-23]. In this study, we enrolled patients with advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis receiving more than three years of treatment with the two agents. Several patients in the LAM-treated arm were also treated with ADV when LAM resistance was detected. We found that patients all benefited from long-term treatment of the two agents and most patients in both arms achieved undetectable HBV DNA and normalization of ALT levels after 3 years of NA treatment. There was no significant difference in HBV DNA suppression, ALT normalization, HBeAg loss, and seroconversion in the LAM-treated and ETV-treated arms. Thus, it raised the question of whether the superior efficacy of 48 wk ETV and LAM therapy proven by the global clinical trials was caused by LAM resistance. We suggest that low genetic barrier NAs such as LAM remain a suitable candidate for management of CHB if viral resistance is well controlled.

Previous studies demonstrated that prolonged treatment with the currently approved NAs (including LAM, ADV, LdT, ETV, TDF) could reduce inflammation grades and fibrosis stages, which results in the prevention of cirrhosis and subsequent hepatic decompensation[24]. It is unclear whether there was any difference among the 5 NAs in the improvement of inflammation and regression of fibrosis. In the current study, we found that long-term treatment with NAs resulted in significant histological improvement. This result indicates that long-term NA therapy improves histological outcome. Moreover, a more significant decline of median Knodell necroinflammatory score was observed in the ETV arm than in the LAM arm. However, the median Ishak fibrosis score was not different between groups. Interestingly, the same conclusion was drawn in a 48-wk study comparing LAM and ETV in the treatment of naïve patients. Our data suggest that patients may benefit more from ETV than LAM therapy in the improvement of inflammation but not in the regression of fibrosis.

Accumulating clinical data have revealed that hepatic fibrosis or cirrhosis can be reversed when active treatment was performed. This result was further proven in our study showing hepatitis B-associated advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis can be regressed or reversed by long-term treatment with NAs. We found that the regression of hepatitis B-associated advanced fibrosis was closely related with baseline fibrotic stage and treatment duration. Interestingly, patients with higher ALT and HBV DNA levels at baseline achieved significant improvement in fibrosis. However, activated hepatic stellate cells were key players in hepatic fibrogenesis and its resolution is closely associated with fibrotic regression[25]. Taken together, we suggest that the regression of hepatitis B associated fibrosis might not simply result from the suppression of HBV DNA and there are probably other benefits caused by long-term NA therapy. It has been proven that long-term therapy with NAs can restore the function of HBV specific T cells[26,27]. Previous studies demonstrated that NA therapy can regulate the immune system[28-30]. Thus, immunomodulation effects of long-term NA treatment may also play a role in the regression of hepatic fibrosis. Hepatic stellate cells play a key role in fibrogenesis and it remains unclear whether NA therapy can directly or indirectly regulate activated hepatic stellate cells. Finally, we believe that significant progress in understanding mechanism of hepatic fibrogenesis and reversion of cirrhosis can eventually translate into more effective treatment strategies for hepatitis B associated fibrosis or cirrhosis.

Chronic hepatitis B (CHB) is caused by hepatits B virus (HBV) infection and can lead to long-term consequences that include liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Both lamivudine (LAM) and entecavir (ETV) are nucleos(t)ide analogues (NAs) that are effective in treating CHB by directly suppressing viral replication. Studies have demonstrated that 48 wk of ETV therapy is superior to LAM in terms of viral suppression, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) normalization and histological improvement. However, there is no comparison of the histological efficacy after long-term treatment of the two agents, especially in CHB patients with significant fibrosis or cirrhosis.

In the treatment for CHB, histological outcome remains an important aspect of efficacy evaluation and contributes to decision making in terms of treatment duration and choice of medication.

Previous studies showed that the histological outcome after 48 wk of ETV therapy was superior to LAM. The authors compared the histological outcome after long-term treatment with ETV monotherapy and LAM-based combination therapy in CHB patients with significant fibrosis or cirrhosis. The results showed that the majority of patients experienced histological improvement in both arms and some patients achieved full reversion of fibrosis or cirrhosis. ETV was superior to LAM-based therapy in improvement of necroinflammatory but not fibrotic outcome.

The results of this study suggest that ETV is superior to LAM-based therapy in improving liver necroinflammation but not fibrosis in CHB patients. Significant fibrosis or cirrhosis can be fully reversed in some patients after long-term treatment.

Liver fibrosis is the excessive accumulation of extracellular matrix proteins that occurs as a result of sustained viral replication and chronic inflammation in CHB and may eventually result in cirrhosis, which is the end stage of fibrosis characterized by replacement of liver tissue with diffuse fibrosis and regenerative nodules.

This is a good retrospective study in which the authors compared the histological outcome of long-term ETV and LAM therapy in CHB patients with significant fibrosis or cirrhosis. The results suggest that ETV is superior to LAM-based therapy in improvement of necroinflammatory but not fibrotic outcome. It is also inspiring that some patients even achieved full reversion of fibrosis or cirrhosis.

P- Reviewer: Penkova-Radicheva MP S- Editor: Wang JL L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Zhang DN

| 1. | Lavanchy D. Hepatitis B virus epidemiology, disease burden, treatment, and current and emerging prevention and control measures. J Viral Hepat. 2004;11:97-107. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kwon H, Lok AS. Hepatitis B therapy. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;8:275-284. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 191] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 195] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Liaw YF, Chu CM. Hepatitis B virus infection. Lancet. 2009;373:582-592. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 929] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 936] [Article Influence: 62.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ma H, Jia J. Why do I treat HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B patients with a nucleoside analogue. Liver Int. 2013;33 Suppl 1:133-136. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Chen SL, Zheng MH, Shi KQ, Yang T, Chen YP. A new strategy for treatment of liver fibrosis: letting MicroRNAs do the job. BioDrugs. 2013;27:25-34. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 28] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kim MN, Kim SU, Kim BK, Park JY, Kim do Y, Ahn SH, Song KJ, Park YN, Han KH. Increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis B patients with transient elastography-defined subclinical cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2015;61:1851-1859. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 111] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Santantonio TA, Fasano M. Chronic hepatitis B: Advances in treatment. World J Hepatol. 2014;6:284-292. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 27] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Dusheiko G. Treatment of HBeAg positive chronic hepatitis B: interferon or nucleoside analogues. Liver Int. 2013;33 Suppl 1:137-150. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 36] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Tujios SR, Lee WM. Update in the management of chronic hepatitis B. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2013;29:250-256. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 31] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Dienstag JL, Schiff ER, Wright TL, Perrillo RP, Hann HW, Goodman Z, Crowther L, Condreay LD, Woessner M, Rubin M. Lamivudine as initial treatment for chronic hepatitis B in the United States. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1256-1263. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1020] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1066] [Article Influence: 42.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Yuen MF, Lai CL. Treatment of chronic hepatitis B: Evolution over two decades. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26 Suppl 1:138-143. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 128] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Fung J, Lai CL, Seto WK, Yuen MF. Nucleoside/nucleotide analogues in the treatment of chronic hepatitis B. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66:2715-2725. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 127] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Gu EL, Yu YQ, Wang JL, Ji YY, Ma XY, Xie Q, Pan HY, Wu SM, Li J, Chen CW. Response-guided treatment of cirrhotic chronic hepatitis B patients: multicenter prospective study. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:653-660. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 3] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Zoulim F. Hepatitis B virus resistance to antiviral drugs: where are we going? Liver Int. 2011;31 Suppl 1:111-116. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 103] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | European Association For The Study Of The Liver. EASL clinical practice guidelines: Management of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2012;57:167-185. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2323] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2338] [Article Influence: 194.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Sherman M, Yurdaydin C, Sollano J, Silva M, Liaw YF, Cianciara J, Boron-Kaczmarska A, Martin P, Goodman Z, Colonno R. Entecavir for treatment of lamivudine-refractory, HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:2039-2049. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 328] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 350] [Article Influence: 19.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Lai CL, Shouval D, Lok AS, Chang TT, Cheinquer H, Goodman Z, DeHertogh D, Wilber R, Zink RC, Cross A. Entecavir versus lamivudine for patients with HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1011-1020. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 18. | Chang TT, Gish RG, de Man R, Gadano A, Sollano J, Chao YC, Lok AS, Han KH, Goodman Z, Zhu J. A comparison of entecavir and lamivudine for HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1001-1010. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 19. | Schiff E, Simsek H, Lee WM, Chao YC, Sette H, Janssen HL, Han SH, Goodman Z, Yang J, Brett-Smith H. Efficacy and safety of entecavir in patients with chronic hepatitis B and advanced hepatic fibrosis or cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:2776-2783. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Du X, Wang J, Shao L, Hu X, Yang C, Shen L, Weng X, Zhang W. Histological improvement of long-term antiviral therapy in chronic hepatitis B patients with persistently normal alanine aminotransferase levels. J Viral Hepat. 2013;20:328-335. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 12] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Schiff ER, Lee SS, Chao YC, Kew Yoon S, Bessone F, Wu SS, Kryczka W, Lurie Y, Gadano A, Kitis G. Long-term treatment with entecavir induces reversal of advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:274-276. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 129] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Chang TT, Liaw YF, Wu SS, Schiff E, Han KH, Lai CL, Safadi R, Lee SS, Halota W, Goodman Z. Long-term entecavir therapy results in the reversal of fibrosis/cirrhosis and continued histological improvement in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2010;52:886-893. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 721] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 717] [Article Influence: 51.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Yokosuka O, Takaguchi K, Fujioka S, Shindo M, Chayama K, Kobashi H, Hayashi N, Sato C, Kiyosawa K, Tanikawa K. Long-term use of entecavir in nucleoside-naïve Japanese patients with chronic hepatitis B infection. J Hepatol. 2010;52:791-799. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 98] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Marcellin P, Asselah T. Long-term therapy for chronic hepatitis B: hepatitis B virus DNA suppression leading to cirrhosis reversal. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28:912-923. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 39] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Lee UE, Friedman SL. Mechanisms of hepatic fibrogenesis. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;25:195-206. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Boni C, Laccabue D, Lampertico P, Giuberti T, Viganò M, Schivazappa S, Alfieri A, Pesci M, Gaeta GB, Brancaccio G. Restored function of HBV-specific T cells after long-term effective therapy with nucleos(t)ide analogues. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:963-73.e9. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 247] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 275] [Article Influence: 22.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 27. | Cooksley H, Chokshi S, Maayan Y, Wedemeyer H, Andreone P, Gilson R, Warnes T, Paganin S, Zoulim F, Frederick D. Hepatitis B virus e antigen loss during adefovir dipivoxil therapy is associated with enhanced virus-specific CD4+ T-cell reactivity. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:312-320. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 46] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Lv J, Jin Q, Sun H, Chi X, Hu X, Yan H, Pan Y, Xiao W, Tian Z, Hou J. Antiviral treatment alters the frequency of activating and inhibitory receptor-expressing natural killer cells in chronic hepatitis B virus infected patients. Mediators Inflamm. 2012;2012:804043. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Ma L, Cai YJ, Yu L, Feng JY, Wang J, Li C, Niu JQ, Jiang YF. Treatment with telbivudine positively regulates antiviral immune profiles in Chinese patients with chronic hepatitis B. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:1304-1311. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 17] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Zhao PW, Jia FY, Shan YX, Ji HF, Feng JY, Niu JQ, Ayana DA, Jiang YF. Downregulation and altered function of natural killer cells in hepatitis B virus patients treated with entecavir. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2013;40:190-196. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |