Published online Nov 28, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i44.16474

Revised: July 28, 2014

Accepted: September 12, 2014

Published online: November 28, 2014

The liver involvement in alcoholic liver disease (ALD) classically ranges from alcoholic steatosis, alcoholic hepatitis or steatohepatitis, alcoholic cirrhosis and even hepatocellular carcinoma. The more commonly seen histologic features include macrovesicular steatosis, neutrophilic lobular inflammation, ballooning degeneration, Mallory-Denk bodies, portal and pericellular fibrosis. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) is a condition with similar histology in the absence of a history of alcohol intake. Although the distinction is essentially based on presence or absence of a history of significant alcohol intake, certain histologic features favour one or the other diagnosis. This review aims at describing the histologic spectrum of alcoholic liver disease and at highlighting the histologic differences between ALD and NASH.

Core tip: Alcoholic steatohepatitis (ASH) is well described. Absence of steatosis should not rule out ASH. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis though histologically similar to ASH, does have important differences, which a pathologist should recognize.

- Citation: Sakhuja P. Pathology of alcoholic liver disease, can it be differentiated from nonalcoholic steatohepatitis? World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(44): 16474-16479

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i44/16474.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i44.16474

The effect of alcohol on the liver has been known since centuries. A PubMed search reveals descriptions of the pathology and ultra-structure in the 1950-1960s[1,2]. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) was first described by Ludwig in 1980 for a set of histological features similar to those of alcoholic hepatitis, which he noted in liver biopsies of patients without a significant history of alcohol intake or any clinical evidence of alcohol abuse[3]. Thus the close similarity of histologic findings in the two entities is obvious, however the differences in histology if any, are not well described. This review intends to describe in detail the histology of alcoholic liver disease (ALD) while highlighting the differences from NAFLD.

Diagnosis of alcoholic liver disease can be made in persons with excessive alcohol intake (20-40 g/d for men and 20 g/d for women) and evidence of liver injury[4]. Histologically the spectrum of liver injury in both ALD and NAFLD can vary from simple steatosis to cirrhosis.

The liver involvement in ALD classically ranges from alcoholic steatosis, alcoholic hepatitis or steatohepatitis (ASH), and alcoholic cirrhosis.

Steatosis is defined as the accumulation of lipid droplets in the hepatocyte cytoplasm. The term “fatty degeneration” has been used when > 5% of hepatocytes show steatosis while fatty liver is the term described when > 50% of hepatocytes show steatosis[5]. Presence of steatosis however is not essential for the diagnosis of ALD as it may even decrease despite continuing alcohol intake and progression of disease[6].

Steatosis can be macrovesicular or microvesicular, depending not only on the size of the lipid droplet accumulated, but also on the pathogenesis and etiology of disease. In ALD the steatosis is usually macrovesicular or mixed microvesicular and macrovesicular. The steatosis begins in the centrilobular Zone 3 and progresses towards the periportal Zone 1. It may begin with small droplets of fat in the cytoplasm (microvesicular), which later enlarge to large fat droplets (macrovesicular), which push the nucleus to the periphery. Macrovesicular fat droplets can coalesce to form fat cysts (large irregular extracellular fat vacuole). Continuing accumulation of fat may lead to rupture of fat cyst with a histiocytic reaction or lipogranuloma. The macrovesicular fat droplets have a high surface/volume ratio and are less susceptible to action of lipases. This allows macrovesicular fat to persist for a few months even after alcohol intake is stopped[7]. Microvesicular steatosis is seen as multiple fat droplets with a central nucleus. Pure microvesicular steatosis may be seen in Alcoholic foamy degeneration. This has not been described in non-ASH (NASH).

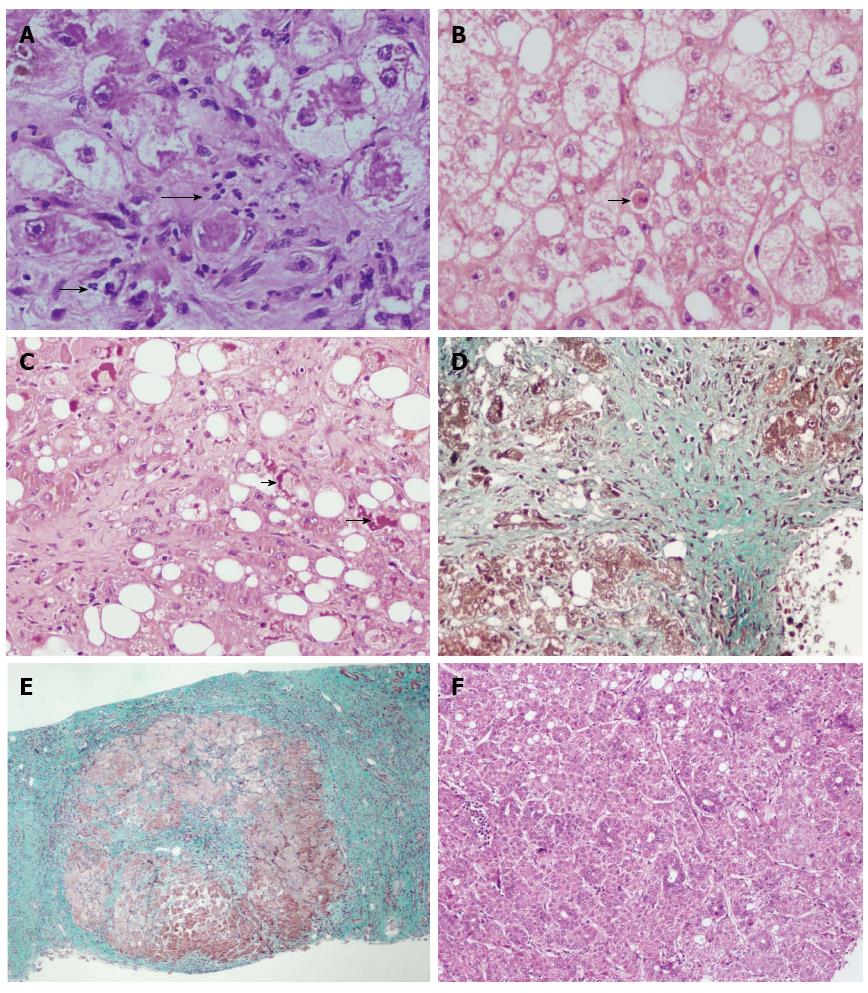

Steatohepatitis indicates evidence of hepatic injury accompanying the steatosis. The injury may be seen in the form of hepatocyte ballooning, neutrophil rich inflammation in the lobular parenchyma (Figure 1), apoptosis or Mallory Denk bodies. Ballooning degeneration of hepatocytes is the predominant mode of cellular injury in alcoholic hepatitis. The hepatocytes are markedly swollen with rarified cytoplasm, clumping of intermediate filaments and loss of staining for cytokeratins 8 and 18. The oncotic swelling as a result of severe ATP depletion and increase in intracellular calcium results in loss of plasma membrane volume control, disruption of intermediate filament network, cell swelling and oncotic necrosis[7]. Lytic necrosis following ballooning degeneration is the commoner form of injury in ASH, however apoptosis can also be seen and indicates either ongoing or current injury. Apoptosis may be triggered by oxidative damage to the mitochondrial inner membrane. The apoptotic hepatocytes (Figure 1), also known as councilman bodies or acidophil bodies, show cell shrinkage, chromatin condensation and nuclear and cellular fragmentation. These are more frequent in NASH than in ASH[8]. Mallory-Denk bodies (MDB) are clumps or skeins of eosinophilic ropy material in the hepatocyte cytoplasm usually in a perinuclear location. Misfolded and aggregated keratin filaments accumulate to form MDB[9]. These are degraded by ubiquination-proteosome pathway to give ubiquitinated keratin, ubiquitinated protein p62, Heat shock proteins 70 and 25. Thus, MDB demonstrate immunoreactivity with antibodies to ubiquitin, keratins 8 and 18, and p62. The formation of MDB could either be a result of toxic damage to the hepatocyte or they may actually contribute to continuing inflammatory injury[7]. Lobular inflammation in ALD is often neutrophil rich and the neutrophils may surround ballooned hepatocytes - “satellitosis”[10]. Portal Inflammation is usually milder than is seen in other forms of chronic hepatitis such as viral hepatitis. Besides lymphocytes and plasma cells, neutrophils, eosinophils and even mast cells can be seen in the inflammatory infiltrate. Portal inflammation is more common and of higher grade in ALD than in NAFLD. It may be accompanied by ductular reaction and periportal fibrosis and may be associated with underlying chronic pancreatitis[11].

Other histologic features described in ALD include glycogenated nuclei, megamitochondria, hemosiderin deposition, cholestasis and ductular reaction[12]. Glycogenated nuclei are nuclear vacuolations in the hepatocyte nuclei. They are more frequent in NAFLD where they are seen in a periportal location.

Fibrosis in alcoholic liver disease begins in Zone 3, perivenular region and extends in a pericellular/perisinusoidal pattern, giving rise to the classic “chicken-wire fibrosis”. A Masson trichrome or Sirius red stain better identifies this. Later the fibrosis progresses to extend to the portal tracts and central-portal or portal-portal bridging fibrosis are seen. Finally, if the alcoholic injury continues, the simultaneous fibrosis and hepatocyte regeneration results in nodule formation and finally cirrhosis[13]. An orcein stain is helpful in later stages to differentiate broad bands of fibrosis (orcein positive) from areas of collapse due to superadded acute alcoholic hepatitis.

Areas of parenchymal extinction are seen as a result of involvement of central and portal veins by the fibrotic process, while ductular reaction is a result of expansion of stem cell compartment[13].

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) can develop in the background of alcoholic liver disease in up to 5%-15% cirrhotics. Alcohol is likely the commonest cause of HCC in the west. Autopsy studies reveal the presence of dysplastic nodules in large cirrhotic regenerative nodules greater than 5 mm in size. These may be precursor lesions to the development of HCC.

The tumor cells may show presence of Mallory hyaline, steatosis and even focal microvesicular foamy degeneration.

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and Alcoholic fatty liver disease, as the name implies, are diseases with differing etiologies and similar morphologic spectrum. The term NAFLD indicates the entire spectrum of fatty liver diseases not related to alcohol intake. Non-alcoholic fatty liver is the term used when there is simple steatosis in the liver not accompanied by inflammation, cell injury or fibrosis. NASH is the term used when steatosis is accompanied by inflammation and cell injury/ballooning degeneration with or without fibrosis. Matteoni et al[14] in 1999 have divided NAFLD into four types or classes based on the clinical spectrum and pathological severity. Class 1 is simple steatosis, class 2 represents steatosis with lobular inflammation, class 3 shows the additional presence of ballooned hepatocytes and class 4 requires the presence of either Mallory’s hyaline or fibrosis. These were correlated with increasing severity of disease and likelihood of progression to cirrhosis.

NAFLD is essentially a clinicopathological diagnosis, wherein clinically, besides ruling out significant alcohol consumption, other causes such as viral hepatitis, autoimmune, A1AT and cholestatic etiologies should be excluded, and evidence of metabolic syndrome[15] should be sought. Minimal histological criteria for diagnosis of NASH were defined at the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases Single Topic Conference on NASH held in September 2002[4] (Table 1). These recommendations though helpful, most pathologists use varying combinations of histologic features to diagnose NASH, but the four most important features are steatosis, ballooning, lobular inflammation and perisinusoidal fibrosis[16].

| Necessary components |

| Steatosis, macro > micro; accentuated in Zone 3 |

| Lobular inflammation, mild; scattered polymorphonuclear leukocytes as well as mononuclear cells |

| Ballooning of hepatocytes; most apparent near steatotic liver cells, in Zone 3 |

| Usually present but not necessary |

| Zone 3 perisinusoidal fibrosis |

| Zone 1 hepatocellular glycogenated nuclei |

| Lipogranulomas in the lobules; usually small |

| Occasional acidophil bodies or periodic acid Schiff-stained Kupffer cells |

| Fat cysts |

| May be present, not necessary |

| Mallory’s hyaline in ballooned hepatocytes - usually Zone 3; typically poorly formed, may require immunostaining for ubiquitin, p62 or CK 7, 18, 19 to confirm |

| Hepatocellular iron, usually grade 1 |

| Megamitochondria in hepatocytes |

Scoring systems for ALD are few and not used frequently. In early stage of disease if clinical history and evaluation point to the diagnosis, a biopsy is often not done. Biopsy is evaluated when advanced diseases is suspected or if diagnosis is in doubt, and thus grading systems are not routinely referred to. Yip and Burt[6] in 2006 proposed a system which may be useful in assessing prognosis, or comparing biopsies in clinical trials (Table 2).

| Grade 0-11 |

| Steatosis |

| 0-3 as in NIDDK NASH CRN |

| Lobular inflammation |

| 0-3 as in NIDDK NASH CRN |

| Cell death |

| 0 none |

| 1 focal apoptosis |

| 2 many acidophil bodies |

| 3 confluent necrosis |

| Ballooning |

| 0-2 as in NIDDK NASH CRN |

| Fibrosis stages 0-6 |

| Stage 1 mild Zone 3 pericellular and/or perivenular |

| Stage 2 marked Zone 3 fibrosis in most zones 3 |

| Stage 3 fibrous linkage HV to septa |

| Stage 4 fibrous linkage HV, PT and septa |

| Stage 5 incomplete or probable cirrhosis |

| Stage 6 definite cirrhosis |

Brunt et al[17] in 1999 proposed a grading and staging system for NASH using steatosis, ballooning, lobular and portal inflammation for the activity grading. Subsequently the pathology subcommittee of the Clinical Research Network for NASH designed and validated a histologic feature scoring system for the full spectrum of lesions of NAFLD. This group evaluated 14 histologic features and after analysis proposed a NAFLD activity score (NAS)[16] (Table 3). Routine hematoxylin and eosin and Masson Trichrome stains are recommended for evaluation. The NAS score specifically included only those features that were related to active injury and were potentially reversible. It has been defined as the un-weighted sum of scores for steatosis (0-3), lobular inflammation (0-3) and ballooning (0-2). The sum is thus 0-8. Fibrosis has been scored separately as in chronic hepatitis scoring systems and is elaborated in greater detail than the previous staging system. The NAS has been defined for the purpose of evaluating histologic changes after therapeutic trials and to assess overall histologic change and not to replace diagnostic criteria or assess severity of NAFLD.

| Item | Definition | Score |

| Steatosis (grade) | Low to medium power evaluation of parenchymal involvement by steatosis | |

| < 5% | 0 | |

| 5%-33% | 1 | |

| > 33%-66% | 2 | |

| > 66% | 3 | |

| Lobular Inflammation | Overall assessment of all inflammatory foci | |

| No foci | 0 | |

| < 2 foci per 200 × field | 1 | |

| 2-4 foci per 200 × field | 2 | |

| > 4 foci per 200 × field | 3 | |

| Ballooning | ||

| None | 0 | |

| Few balloon cells | 1 | |

| Many cells/prominent ballooning | 2 | |

| Fibrosis stage | ||

| None | 0 | |

| Perisinusoidal or periportal | 1 | |

| Mild, Zone 3, perisinusoidal | 1A | |

| Moderate, Zone 3, perisinusoidal | 1B | |

| Portal/periportal | 1C | |

| Perisinusoidal and portal/periportal | 2 | |

| Bridging fibrosis | 3 | |

| Cirrhosis | 4 |

Inter and intra-observer variation may be present as in other grading systems. The degree of steatosis may be over or underestimated based on the power at which observations are made. For example small droplet steatosis may be missed on low power examination and may lead to underestimation of grade of steatosis. Estimation at × 20 objective magnification is recommended. Hall et al[18] have shown that hepatopathologists show “excellent” inter-observer agreement in estimated fat proportionate area, however measured fat proportionate area using digital image analysis is more accurate. Degree of ballooning may be difficult to grade when steatosis is extensive.

Historically, NASH was described as a result of its morphologic similarity to Alcoholic Steatohepatitis. Thus the overlap in histologic features is prominent; however alcoholic liver disease shows more sever disease histology at the time of biopsy. Whether this is a function of greater toxic injury due to repeated bouts of alcohol abuse, or because liver biopsy is rarely performed in the early stage of disease when a clinical diagnosis is obvious, is debatable. Despite the commonality in the histologic features in ASH and NASH, some feature are rarely seen or not reported in NASH (Table 4). Sclerosing hyaline necrosis is characterized by perivenular liver cell necrosis with fibrosis in the same region. This may result in occlusion of the terminal hepatic venules and precirrhotic portal hypertension[19]. Alcoholic foamy degeneration was described by Uchida et al[20] in a set of 20 patients who recovered rapidly once the alcohol was withdrawn. The hepatocytes show a diffuse prominent microvesicular fatty change (may be more in perivenular zone), with minimal inflammation and MDB are either minimal or absent. Perivenular hepatocytic and canalicular cholestasis may be associated. Goodman and Ishak[21] have described three types of vascular lesions in an autopsy series of ALD. These include lymphocytic phlebitis, phlebosclerosis (narrowing of the hepatic vein lumen) and veno-occlusive lesions. Phlebosclerosis is seen in all cases of ASH. Cholestasis is seen in severe fatty liver, alcoholic foamy degeneration and can be seen in alcoholic hepatitis and decompensated alcoholic cirrhosis. Liver histology may show cholestasis, marginal ductular proliferation, cholangiolitis and portal tract edema. Adaptive changes such as oncotic or groundglass change in cytoplasm of hepatocytes can be seen in advanced ALD. These may reflect increased numbers of mitochondria or smooth endoplasmic reticulum respectively[6].

| NAFLD (NASH) | ALD |

| Usually mild disease | Varying severity |

| Bridging necrosis rare | Bridging necrosis common |

| Poorly formed MH | Well formed MH |

| -/rare | Sclerosing hyaline necrosis |

| -/rare | Phlebosclerosis |

| -/rare | Canalicular cholestasis |

| Not described | Foamy degeneration |

| Nuclear vacuolation - more common | Nuclear vacuolation - less common |

| Presence of Iron/hemosiderin is less frequent | Presence of Iron/hemosiderin is more frequent |

| Ductular reaction is less frequent/prominent | Ductular reaction is more frequent/prominent |

| Fibrosis/cirrhosis - less common | Fibrosis/cirrhosis - more common |

Pinto et al[22] studied the histologic features of liver biopsy in 32 non-alcoholics, 21 asymptomatic ambulatory and 52 hospitalized patients of alcoholic hepatitis. Histologic findings in the ambulatory alcoholic group were intermediate between the other two groups with nonalcoholic group having least degree of severity of hepatocellular damage, inflammation, MDB and fibrosis. The obese, diabetic non-alcoholics had significant fibrosis in 47% and cirrhosis in 8% while 38% of ambulatory and 89% of hospitalized alcoholic hepatitis patients had cirrhosis.

Singh et al[23] also compared the liver histology in alcoholic versus non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. They reported more severe ballooning degeneration of hepatocytes, portal inflammation, prominent MDB, neutrophil-rich inflammation, and fibrosis in ASH as compared to NASH. Cholestasis and bile ductular proliferation were observed only in ASH.

The differentiation between the two conditions becomes even more difficult in overlapping clinical scenarios such as obese alcoholics, alcoholics with diabetes and obese or diabetic individuals with a borderline alcohol intake. The degree of injury caused by alcohol varies greatly in different individuals due to various genetic factors.

Although liver biopsy is not essential in a clinical setting of ALD wherein the history of alcohol abuse is forthcoming, it may be useful in the following settings: (1) To look for or rule out the presence of a coexisting etiology for liver injury which may be seen in up to 20% of patients[24]; (2) To assess the severity of liver injury and the stage of fibrosis, especially in patients who do not have decompensated liver disease; (3) The liver biopsy may also give helpful prognostic information. The severity of inflammation, presence of neutrophils and presence of cholestatic changes may indicate poorer prognosis while presence of megamitochondria indicates a better prognosis, long-term survival with fewer complications and slower progression to cirrhosis[25]; (4) In patients where the history of alcohol use is suspected but not forthcoming or there may be a possibility of both ALD and NAFLD; (5) In severe forms of ALD where specific treatment modality is to be given (such as corticosteroids or pentoxyphylline); (6) Patients who are to be enrolled in a clinical trial; and (7) Where acute-on-chronic liver injury is suspected.

However, the decision to biopsy has to be taken for each individual case based on a balance between the information it can provide, the impact on treatment and the risk of complications.

Before designating a biopsy as alcoholic steatohepatitis, in a liver biopsy showing histology of steatohepatitis, a clinical history of significant alcohol intake must be sought. For a pathologist where details such as quantum and frequency of alcohol intake may not be clearly mentioned on the requisition form, this diagnosis is based only on a brief input from the clinician. Furthermore, there is a distinct possibility of the patient having additional clinical features of metabolic syndrome. Thus a report stating that the histology is “consistent” with alcoholic steatohepatitis is more accurate. In cases where history of alcohol intake or features related to metabolic syndrome and other causes of steatohepatitis are not clearly stated, a morphologic diagnosis alone should be given with clinical possibilities stated in order of likelihood based on the morphology. For example, a liver biopsy clearly showing about 40% macrovesicular steatosis, associated with ballooning degeneration of hepatocytes, well defined Mallory hyaline and a neutrophil-rich lobular inflammation with a mild portal inflammation, may be reported as “Steatohepatitis - possibly alcohol related” - clinical correlation required.

Additional information such as the degree of steatosis and grading and staging of the biopsy may be helpful. Prussian blue stain for iron overload may also be helpful especially in alcoholic liver disease.

P- Reviewer: Prieto J, Videla LA S- Editor: Gou SX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Albot G, Herman J, Corteville M. [Clinical, biological and histological study of the development of steatosis into alcoholic cirrhosis of the liver]. Presse Med. 1953;61:589-593. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Klion FM, Schaffner F. Ultrastructural studies in alcoholic liver disease. Digestion. 1968;1:2-14. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Ludwig J, Viggiano TR, McGill DB, Oh BJ. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: Mayo Clinic experiences with a hitherto unnamed disease. Mayo Clin Proc. 1980;55:434-438. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Caldwell SH. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: summary of an AASLD Single Topic Conference. Hepatology. 2003;37:1202-1219. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Tannapfel A, Denk H, Dienes HP, Langner C, Schirmacher P, Trauner M, Flott-Rahmel B. Histopathological diagnosis of non-alcoholic and alcoholic fatty liver disease. Virchows Arch. 2011;458:511-523. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 91] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Yip WW, Burt AD. Alcoholic liver disease. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2006;23:149-160. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Crawford JM. Histologic findings in alcoholic liver disease. Clin Liver Dis. 2012;16:699-716. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 37] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Feldstein AE, Gores GJ. Apoptosis in alcoholic and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Front Biosci. 2005;10:3093-3099. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | Denk H, Stumptner C, Zatloukal K. Mallory bodies revisited. J Hepatol. 2000;32:689-702. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Lefkowitch JH. Morphology of alcoholic liver disease. Clin Liver Dis. 2005;9:37-53. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Yeh MM, Brunt EM. Pathology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Am J Clin Pathol. 2007;128:837-847. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 12. | Tiniakos DG. Liver biopsy in alcoholic and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis patients. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2009;33:930-939. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 23] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Theise ND. Histopathology of alcoholic liver disease. Clin Liver Dis. 2013;2:64-67. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 35] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Matteoni CA, Younossi ZM, Gramlich T, Boparai N, Liu YC, McCullough AJ. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a spectrum of clinical and pathological severity. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:1413-1419. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 15. | Kassi E, Pervanidou P, Kaltsas G, Chrousos G. Metabolic syndrome: definitions and controversies. BMC Med. 2011;9:48. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 916] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 819] [Article Influence: 63.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kleiner DE, Brunt EM, Van Natta M, Behling C, Contos MJ, Cummings OW, Ferrell LD, Liu YC, Torbenson MS, Unalp-Arida A. Design and validation of a histological scoring system for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2005;41:1313-1321. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 17. | Brunt EM, Janney CG, Di Bisceglie AM, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Bacon BR. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a proposal for grading and staging the histological lesions. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:2467-2474. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 18. | Hall AR, Dhillon AP, Green AC, Ferrell L, Crawford JM, Alves V, Balabaud C, Bhathal P, Bioulac-Sage P, Guido M. Hepatic steatosis estimated microscopically versus digital image analysis. Liver Int. 2013;33:926-935. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 30] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Brunt EM, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Burt AD. Fatty liver disease: alcoholic and non-alcoholic. In MacSween’s Pathology of the Liver. 6th ed. Toronto: Chrchill Livingstone Elsevier 2012; . [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 20. | Uchida T, Kao H, Quispe-Sjogren M, Peters RL. Alcoholic foamy degeneration--a pattern of acute alcoholic injury of the liver. Gastroenterology. 1983;84:683-692. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 21. | Goodman ZD, Ishak KG. Occlusive venous lesions in alcoholic liver disease. A study of 200 cases. Gastroenterology. 1982;83:786-796. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 22. | Pinto HC, Baptista A, Camilo ME, Valente A, Saragoça A, de Moura MC. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Clinicopathological comparison with alcoholic hepatitis in ambulatory and hospitalized patients. Dig Dis Sci. 1996;41:172-179. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 23. | Singh DK, Rastogi A, Sakhuja P, Gondal R, Sarin SK. Comparison of clinical, biochemical and histological features of alcoholic steatohepatitis and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in Asian Indian patients. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2010;53:408-413. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | O’Shea RS, Dasarathy S, McCullough AJ; Practice Guideline Committee of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases; Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology. 2010;51:307-328. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 837] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 795] [Article Influence: 56.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 25. | Chedid A, Mendenhall CL, Tosch T, Chen T, Rabin L, Garcia-Pont P, Goldberg SJ, Kiernan T, Seeff LB, Sorrell M. Significance of megamitochondria in alcoholic liver disease. Gastroenterology. 1986;90:1858-1864. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |