Published online Nov 21, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i43.16306

Revised: June 8, 2014

Accepted: July 11, 2014

Published online: November 21, 2014

AIM: To evaluate the diagnostic characteristics of magnifying endoscopy with acetic acid spray and narrow-band imaging (MA-NBI) for early colorectal cancer.

METHODS: We conducted a prospective study to evaluate the diagnostic characteristics of MA-NBI in differentiating early colorectal adenocarcinomas from adenomas. To compare the results, we used magnifying endoscopy with NBI (M-NBI) and magnifying endoscopy with crystal violet staining (M-CV). The study was performed in 2 phases. In phase 1, 10 colonoscopists at our institution were shown still photographs of 35 colorectal polyps (24 adenocarcinomas and 11 adenomas) in M-NBI, MA-NBI, and M-CV. They made diagnostic predictions using a five-grade scoring evaluation. We plotted receiver operating characteristic curves and compared the areas under the curves (AUCs). In phase 2, colorectal polyps measuring ≥ 8 mm were prospectively enrolled. During real-time colonoscopy, one of the 7 colonoscopists scored the lesion as an adenocarcinoma or an adenoma and assigned a level of confidence to the prediction (high or low). We calculated the accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) for each method and compared the proportions of high-confidence predictions.

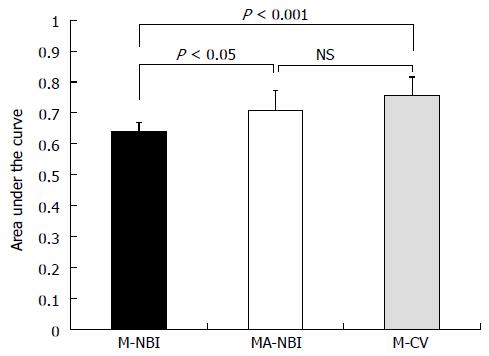

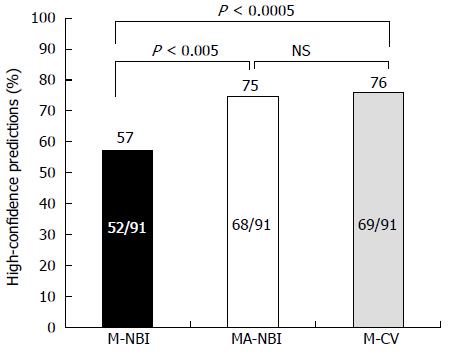

RESULTS: In phase 1, the mean ± SD AUCs were 0.64 ± 0.031 in M-NBI, 0.71 ± 0.066 in MA-NBI, and 0.76 ± 0.059 in M-CV (P < 0.05 for M-NBI vs MA-NBI, P < 0.001 for M-NBI vs M-CV, and not significant for MA-NBI vs M-CV). In phase 2, 84 patients with 91 lesions (46 adenocarcinomas and 45 adenomas) were enrolled. The diagnostic characteristics were as follows: 73% accuracy, 85% sensitivity, 60% specificity, 68% PPV, and 79% NPV in M-NBI; 73% accuracy, 80% sensitivity, 64% specificity, 70% PPV, and 76% NPV in MA-NBI; and 73% accuracy, 83% sensitivity, 62% specificity, 69% PPV, and 78% NPV in M-CV. The proportions of high-confidence predictions were 57% in M-NBI, 75% in MA-NBI, and 76% in M-CV (P < 0.005 for M-NBI vs MA-NBI, P < 0.0005 for M-NBI vs M-CV, and P = 1.0 for MA-NBI vs M-CV).

CONCLUSION: MA-NBI is useful for differentiating early colorectal adenocarcinomas from adenomas.

Core tip: Differentiating early colorectal adenocarcinomas from adenomas using magnifying endoscopy with narrow-band imaging can sometimes be difficult because the surface pattern is frequently obscure. Magnifying endoscopy with acetic acid spray and narrow-band imaging (MA-NBI) accentuates the surface pattern of colorectal polyps. This study showed that MA-NBI and magnifying endoscopy with crystal violet staining (M-CV) are useful for differentiating early colorectal adenocarcinomas from adenomas. Moreover, MA-NBI is more time- and cost-effective than M-CV and could be beneficial for routine colonoscopies in terms of diagnostic accuracy, efficiency, and cost-effectiveness.

- Citation: Goto N, Kusaka T, Tomita Y, Tanaka H, Itokawa Y, Koshikawa Y, Yamaguchi D, Nakai Y, Fujii S, Kokuryu H. Magnifying narrow-band imaging with acetic acid to diagnose early colorectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(43): 16306-16310

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i43/16306.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i43.16306

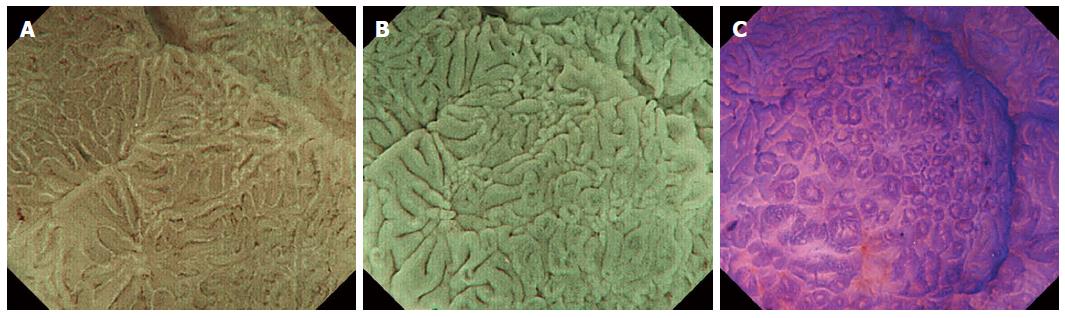

Magnifying endoscopy with narrow-band imaging (M-NBI) is useful for differentiating neoplastic from non-neoplastic colorectal polyps and for estimating the depth of invasion of early colorectal cancers[1,2]. Differentiating early colorectal adenocarcinomas from adenomas using M-NBI is sometimes difficult because the surface pattern is frequently obscure and the vascular pattern does not directly reflect structural atypia. Magnifying endoscopy with crystal violet staining (M-CV) provides a clear pit pattern image[3,4]; however, M-CV is a time-consuming procedure. Magnifying endoscopy with acetic acid spray and narrow-band imaging (MA-NBI) quickly accentuates the surface pattern through the acetowhite reaction (Figure 1). The usefulness of this method has been reported for differentiating neoplastic from non-neoplastic colorectal polyps[5]; however, this usefulness has not been reported for differentiating early colorectal adenocarcinomas from adenomas. The aim of this study was to evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of MA-NBI for differentiating early colorectal adenocarcinomas from adenomas and to compare the accuracy with those of M-NBI and M-CV.

We conducted a prospective study to compare the diagnostic characteristics of M-NBI, MA-NBI, and M-CV for differentiating early colorectal adenocarcinomas from adenomas. The study was conducted in 2 phases. Phase 1 compared the diagnostic characteristics of M-MBI, MA-NBI, and M-CV using still photographs of known histology, and phase 2 compared these diagnostic characteristics during real-time colonoscopy. The study was approved by the institutional committee. The patients involved in the real-time colonoscopy study provided written informed consent. The study was conducted according to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Phase 1: Between January 2012 and January 2013, a total of 562 polyps were treated by endoscopic mucosal resection or endoscopic submucosal dissection at our institution. We reviewed all recorded photographs of these polyps and noted that 35 polyps (24 adenocarcinomas and 11 adenomas) had clear photographs of M-NBI, MA-NBI, and M-CV at the same magnification ratio, such as the images shown in Figure 1. Ten colonoscopists with 3 to 21 years of colonoscopy experience participated in the study. The colonoscopists were independently shown the still photographs of these 35 polyps in each modality and made diagnostic predictions of adenocarcinoma or adenoma using a five-grade evaluation score. We plotted receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for each modality for the 10 colonoscopists and compared the areas under the curves (AUCs).

Phase 2: We prospectively enrolled patients who underwent routine screening or diagnostic colonoscopy and had polyps measuring ≥ 8 mm that had not previously been biopsied for histological examination. Hyperplastic polyps, sessile serrated adenomas/polyps, hamartomatous polyps and advanced cancers were excluded from the study. Seven colonoscopists with 3 to 21 years of colonoscopy experience participated in the study. Before resection, one of the colonoscopists examined the lesion in M-NBI, MA-NBI, and M-CV. For each modality, during the examination, the colonoscopist scored the lesion as an adenocarcinoma or adenoma and immediately assigned a level of confidence (high or low) to the prediction. The colonoscopists were instructed to assign a prediction with high confidence when they had > 90% certainty regarding the diagnosis. Colonoscopies were performed using high-definition endoscopes (CF-H260AZI or CF-HQ290, with an Evis Lucera Elite CV-290 light source, CLV-290 processor, and OEV-261H monitor; all from Olympus, Japan). For MA-NBI, we sprayed 5 mL of a 1.5% acetic acid solution on the lesion and immediately examined the lesion. For M-CV, we sprayed a 0.2% crystal violet solution on the lesion, waited more than one minute, washed off the superfluous solution with water, and examined the lesion. After the examination, the lesion was resected and retrieved, and an independent pathologist who was blinded to the endoscopic prediction reported the histology of the lesion, according to the Vienna classification[6]. We compared the diagnostic characteristics and the proportions in which the predictions were made with high confidence.

In phase 1, the Dorfman-Berbaum-Metz multiple-reader multiple-case (DBM-MRMC) software was used to fit the ROC curve and to calculate the AUCs. Comparisons of the AUCs were performed using Tukey’s post-hoc test. In phase 2, we calculated the accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity, as well as the positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV). The comparisons of paired proportions were performed using McNemar’s test. The comparisons of categorical data were performed using Fisher’s exact test. All reported P values were two-sided.

The mean ± SD AUCs were 0.64 ± 0.031 for M-NBI, 0.71 ± 0.066 for MA-NBI, and 0.76 ± 0.059 for M-CV (P < 0.05 for M-NBI vs MA-NBI, P < 0.001 for M-NBI vs M-CV, and not significant for MA-NBI vs M-CV) (Figure 2).

Between July 2013 and December 2013, a total of 84 patients with 91 polyps fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were prospectively enrolled in the study. The lesions consisted of 46 adenocarcinomas with a median size of 12.5 mm (range, 8-35 mm), and 45 adenomas with a median size of 10 mm (range, 8-23 mm). Of the 46 adenocarcinomas, 38 were intramucosal cancers, and 8 were submucosal cancers. The diagnostic characteristics were 73% accuracy, 85% sensitivity, 60% specificity, 68% PPV, and 79% NPV in M-NBI; 73% accuracy, 80% sensitivity, 64% specificity, 70% PPV, and 76% NPV in MA-NBI; and 73% accuracy, 83% sensitivity, 62% specificity, 69% PPV, and 78% NPV in M-CV (Table 1). The proportions of high-confidence predictions were 57% (52/91) in M-NBI, 75% (68/91) in MA-NBI, and 76% (69/91) in M-CV (P < 0.005 for M-NBI vs MA-NBI, P < 0.0005 for M-NBI vs M-CV, and P = 1.0 for MA-NBI vs M-CV) (Figure 3). When the predictions were made with high confidence, the accuracy, specificity, and PPV were significantly higher in MA-NBI; the accuracy, sensitivity, and PPV were also significantly higher in M-CV, whereas the diagnostic characteristics did not differ significantly in M-NBI (Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4). We also plotted ROC curves for each modality. The AUCs were 0.79 in M-NBI, 0.82 in MA-NBI, and 0.85 in M-CV. There were no significant differences among the three modalities.

| M-NBI | MA-NBI | M-CV | |

| Accuracy (95%CI) | 73% (63%-81%) | 73% (63%-81%) | 73% (63%-81%) |

| Sensitivity (95%CI) | 85% (71%-93%) | 80% (67%-90%) | 83% (69%-91%) |

| Specificity (95%CI) | 60% (45%-73%) | 64% (50%-77%) | 62% (48%-75%) |

| PPV (95%CI) | 68% (55%-79%) | 70% (56%-81%) | 69% (56%-80%) |

| NPV (95%CI) | 79% (36%-90%) | 76% (61%-87%) | 78% (62%-89%) |

| High-confidence predictions(n = 52) | Low-confidence predictions(n = 39) | P value for high-confidence vs low-confidence predictions | |

| Accuracy (95%CI) | 79% (66%-88%) | 64% (48%-77%) | 0.16 |

| Sensitivity (95%CI) | 87% (70%-95%) | 81% (56%-94%) | 0.68 |

| Specificity (95%CI) | 68% (47%-84%) | 52% (33%-71%) | 0.37 |

| PPV (95%CI) | 79% (62%-90%) | 54% (35%-72%) | 0.08 |

| NPV (95%CI) | 79% (56%-92%) | 80% (54%-94%) | 1.00 |

| High-confidence predictions(n = 68) | Low-confidence predictions(n = 23) | P value for high-confidence vs low-confidence predictions | |

| Accuracy (95%CI) | 79% (68%-87%) | 52% (36%-71%) | 0.02 |

| Sensitivity (95%CI) | 83% (67%-92%) | 70% (39%-90%) | 0.69 |

| Specificity (95%CI) | 76% (59%-87%) | 39% (18%-65%) | 0.04 |

| PPV (95%CI) | 78% (63%-89%) | 47% (25%-70%) | 0.04 |

| NPV (95%CI) | 81% (63%-91%) | 63% (30%-90%) | 0.35 |

| High-confidence predictions(n = 69) | Low-confidence predictions(n = 22) | P value for high-confidence vs low-confidence predictions | |

| Accuracy (95%CI) | 81% (70%-88%) | 46% (27%-65%) | 0.002 |

| Sensitivity (95%CI) | 92% (78%-98%) | 38% (13%-70%) | 0.002 |

| Specificity (95%CI) | 68% (50%-82%) | 50% (27%-73%) | 0.330 |

| PPV (95%CI) | 78% (64%-88%) | 30% (10%-61%) | 0.006 |

| NPV (95%CI) | 88% (68%-96%) | 58% (32%-81%) | 0.090 |

The usefulness of acetic acid spray has predominantly been reported in the fields of Barrett’s esophagus and early gastric cancer[7,8]. The usefulness of this method in colonoscopy has only been reported for differentiating neoplastic from non-neoplastic polyps[5], in which M-NBI without acetic acid spray also has excellent diagnostic accuracy[9]. In this study, we aimed to compare the diagnostic characteristics of M-NBI, MA-NBI, and M-CV in differentiating early colorectal adenocarcinomas from adenomas. In phase 1, the AUCs for MA-NBI and M-CV were significantly higher than the AUC for M-NBI. This result, however, only reflects the evaluation of still photographs of magnifying endoscopy. During routine colonoscopy, we first make a prediction based on the findings without optical magnification; then, we magnify the area of interest and spray acetic acid or crystal violet dyes, as necessary. To clarify the role that MA-NBI plays in routine colonoscopy, we evaluated the diagnostic characteristics during real-time colonoscopy in phase 2 of the study. Although the accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV and the AUCs were somewhat identical among the three modalities, MA-NBI and M-CV significantly increased the high-confidence predictions with higher accuracy compared with M-NBI.

MA-NBI and M-CV efface the vascular pattern and provide a clear surface pattern that directly reflects the glandular structure of the lesion observed during the histopathological examination. However, there is a difference in the surface patterns between MA-NBI and M-CV (Figure 1). MA-NBI does not clarify a rough margin, a narrow lumen, or absent staining, all of which could be observed in M-CV and are important in distinguishing between mildly irregular and severely irregular type V (I) pit patterns for estimating the depth of cancer invasion. This study suggests that in terms of differentiating adenocarcinomas from adenomas, the enhanced surface pattern in MA-NBI could be as informative as the pit pattern in M-CV.

Recently, there has been a trend toward the resect-and-discard policy, in which colonoscopists resect polyps measuring < 10 mm based on the optical diagnosis and discard the samples without submitting them to pathology[10,11]. The aim of the resect-and-discard policy was to reduce the volume of histology by diagnosing and treating many obvious benign adenomas and rectosigmoid hyperplastic polyps; polyps should be sent for pathology when the optical diagnosis is not definitive. In the Detect InSpect ChAracterise Resect and Discard (DISCARD) trial, polyps measuring 6-9 mm were sent for pathology more often than polyps measuring ≤ 5 mm (22% vs 8%, respectively), showing the difficulty and importance of making high-confidence predictions for larger polyps. Our study showed that even for polyps measuring ≥ 8 mm, MA-NBI and M-CV facilitate high-confidence predictions with high accuracy. Moreover, MA-NBI is more time- and cost-effective than M-CV; the time required to obtain a clear image is approximately 14 s in MA-NBI[5], whereas more than one minute is required in M-CV. Therefore, we believe that MA-NBI could play an important role in routine colonoscopy.

This study has limitations. Because of the small sample size in phase 2, we could not show a significant increase in the overall accuracy or in the AUCs. In addition, although 10 colonoscopists with different experience levels participated, this work is a single-center study in Japan; thus, it might be difficult to extrapolate the results to colonoscopists who are not experienced with magnifying endoscopy.

We have shown that MA-NBI is useful for differentiating early colorectal adenocarcinomas from adenomas; MA-NBI could benefit routine colonoscopy in terms of the diagnostic accuracy, efficiency and cost-effectiveness.

The authors thank Dr. Yasutaka Tanaka and Dr. Tomohiko Usui for their cooperation with the study.

Differentiating early colorectal adenocarcinomas from adenomas using magnifying endoscopy with narrow-band imaging (M-NBI) can sometimes be difficult because the surface pattern is frequently obscure and the vascular pattern does not directly reflect structural atypia. Although magnifying endoscopy with crystal violet staining (M-CV) provides a clear pit pattern image, it is a time-consuming procedure.

Magnifying endoscopy with acetic acid spray and narrow-band imaging (MA-NBI) accentuates the surface pattern of colorectal polyps and is more time-saving than M-CV. The usefulness of this method has been reported for differentiating neoplastic from non-neoplastic colorectal polyps; however, the usefulness for differentiating early colorectal adenocarcinomas from adenomas has not been reported.

This prospective study is the first to show that MA-NBI and M-CV are useful for differentiating early colorectal adenocarcinomas from adenomas. The results suggest that we could substitute MA-NBI for M-CV to differentiate early colorectal adenocarcinomas from adenomas.

MA-NBI could play an integral role in routine colonoscopy because differentiating early colorectal adenocarcinomas from adenomas is of great importance. MA-NBI could confer a benefit in terms of the diagnostic accuracy, efficiency, and cost-effectiveness.

For MA-NBI, we sprayed 5 mL of a 1.5% acetic acid solution on the lesion and immediately examined the lesion. For M-CV, we sprayed a 0.2% crystal violet solution on the lesion, waited more than one minute, washed off the superfluous solution with water, and examined the lesion.

To evaluate the diagnostic characteristics of MA-NBI in early colorectal cancer, the authors conducted a two-phase prospective study and concluded that MA-NBI was useful for differentiating early colorectal adenocarcinomas from adenomas. The data presented likely sufficiently support the conclusion made by the authors. The information provided might be helpful for promoting further advances in the early diagnosis of colorectal cancer.

P- Reviewer: Nishiyama M, Wang SK, Wang YD S- Editor: Nan J L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang DN

| 1. | Hewett DG, Kaltenbach T, Sano Y, Tanaka S, Saunders BP, Ponchon T, Soetikno R, Rex DK. Validation of a simple classification system for endoscopic diagnosis of small colorectal polyps using narrow-band imaging. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:599-607.e1. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 376] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 384] [Article Influence: 32.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ikematsu H, Matsuda T, Emura F, Saito Y, Uraoka T, Fu KI, Kaneko K, Ochiai A, Fujimori T, Sano Y. Efficacy of capillary pattern type IIIA/IIIB by magnifying narrow band imaging for estimating depth of invasion of early colorectal neoplasms. BMC Gastroenterol. 2010;10:33. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 156] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kudo S, Tamura S, Nakajima T, Yamano H, Kusaka H, Watanabe H. Diagnosis of colorectal tumorous lesions by magnifying endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;44:8-14. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 721] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 655] [Article Influence: 23.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kanao H, Tanaka S, Oka S, Kaneko I, Yoshida S, Arihiro K, Yoshihara M, Chayama K. Clinical significance of type V(I) pit pattern subclassification in determining the depth of invasion of colorectal neoplasms. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:211-217. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 59] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 59] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Togashi K, Hewett DG, Whitaker DA, Hume GE, Francis L, Appleyard MN. The use of acetic acid in magnification chromocolonoscopy for pit pattern analysis of small polyps. Endoscopy. 2006;38:613-616. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 24] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Schlemper RJ, Riddell RH, Kato Y, Borchard F, Cooper HS, Dawsey SM, Dixon MF, Fenoglio-Preiser CM, Fléjou JF, Geboes K. The Vienna classification of gastrointestinal epithelial neoplasia. Gut. 2000;47:251-255. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1463] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1470] [Article Influence: 61.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Guelrud M, Herrera I, Essenfeld H, Castro J. Enhanced magnification endoscopy: a new technique to identify specialized intestinal metaplasia in Barrett’s esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:559-565. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 195] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 195] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Eleftheriadis N, Inoue H, Ikeda H, Onimaru M, Yoshida A, Maselli R, Santi G, Kudo SE. Acetic acid spray enhances accuracy of narrow-band imaging magnifying endoscopy for endoscopic tissue characterization of early gastric cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79:712. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sano Y, Ikematsu H, Fu KI, Emura F, Katagiri A, Horimatsu T, Kaneko K, Soetikno R, Yoshida S. Meshed capillary vessels by use of narrow-band imaging for differential diagnosis of small colorectal polyps. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:278-283. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 208] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 194] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ignjatovic A, East JE, Suzuki N, Vance M, Guenther T, Saunders BP. Optical diagnosis of small colorectal polyps at routine colonoscopy (Detect InSpect ChAracterise Resect and Discard; DISCARD trial): a prospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:1171-1178. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 264] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 292] [Article Influence: 19.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Rex DK. Narrow-band imaging without optical magnification for histologic analysis of colorectal polyps. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1174-1181. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 202] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 216] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |