Published online Jul 21, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i27.9205

Revised: February 14, 2014

Accepted: March 4, 2014

Published online: July 21, 2014

Thermal injuries of the esophagus are rare causes of benign esophageal stricture, and all published cases were successfully treated with conservative management. A 28-year-old Japanese man with a thermal esophageal injury caused by drinking a cup of hot coffee six months earlier was referred to our hospital. The hot coffee was consumed in a single gulp at a party. Although the patient had been treated conservatively at another hospital, his symptoms of dysphagia gradually worsened after discharge. An upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and computed tomography revealed a pin-hole like area of stricture located 19 cm distally from the incisors to the esophagogastric junction, as well as circumferential stenosis with notable wall thickness at the same site. The patient underwent a thoracoscopic esophageal resection with reconstruction using ileocolon interposition. The pathological findings revealed wall thickening along the entire length of the esophagus, with massive fibrosis extending to the muscularis propria and adventitia at almost all levels. Treatment with balloon dilation for long areas of stricture is generally difficult, and stent placement in patients with benign esophageal stricture, particularly young patients, is not yet widely accepted due to the incidence of late adverse events. Considering the curability and quality-of-life associated with a long expected prognosis, we determined that surgery was the best treatment option for this young patient. In this case, we decided to perform an esophagectomy and reconstruction with ileocolon interposition in order to preserve the reservoir function of the stomach and to avoid any problems related to the reflux of gastric contents. In conclusion, resection of the esophagus is a treatment option in patients with benign esophageal injury, especially in cases involving young patients with refractory esophageal stricture. In addition, ileocolon interposition may help to improve the quality-of-life of patients.

Core tip: This is a very rare case of the refractory esophageal thermal injury which required the esophagectomy. In general, there are several non-surgical options available to treat benign esophageal stricture. However, considering the curability and quality-of-life associated with a long expected prognosis, we determined that esophagectomy with ileocolon interposition was the most proper treatment option for this young patient.

- Citation: Kitajima T, Momose K, Lee S, Haruta S, Shinohara H, Ueno M, Fujii T, Udagawa H. Benign esophageal stricture after thermal injury treated with esophagectomy and ileocolon interposition. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(27): 9205-9209

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i27/9205.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i27.9205

Although benign esophageal stricture can be induced by several causes, thermal injuries of the esophagus caused by swallowing extremely hot foreign bodies are uncommon[1,2]. There are only a few case reports of thermal injury to the esophagus, all of which were successfully treated with conservative management[2-8]. In patients who receive non-surgical treatments that ultimately prove ineffective, such as balloon dilation and stent placement, surgery is typically the only remaining therapeutic option; however, the procedure is highly invasive. Moreover, when treating young patients for benign esophageal stricture, it is important that surgeons preserve digestive function and improve the quality-of-life of the patient. A previous report indicated that ileocolon interposition after gastrectomy or distal esophagectomy is superior to the placement of a gastric conduit as an esophageal substitute with respect to quality-of-life[9,10]; in addition, a favorable outcome of ileocolon interposition following esophagectomy for esophageal cancer was described in our previous report[11]. We herein report a case of benign esophageal stricture caused by thermal injury that was successfully treated with esophageal resection and ileocolon interposition, additionally providing a review of the pertinent literature.

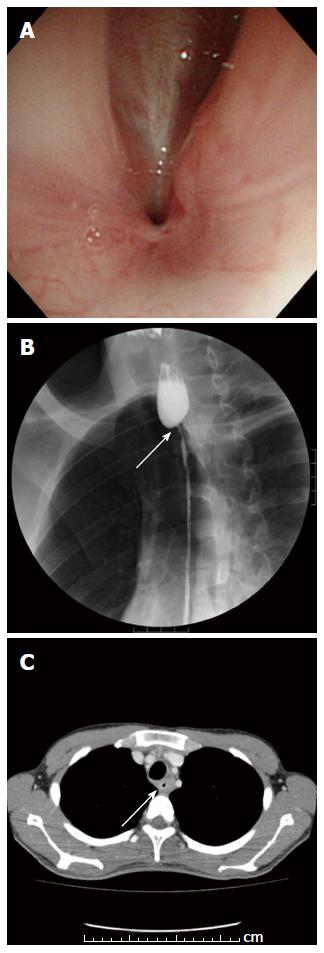

A 28-year-old Japanese young man with a history of a thermal esophageal injury six months earlier that had been treated conservatively at another hospital was referred to our hospital. He had consumed a cup of coffee in a single gulp at a party and was later examined at the medical department of another hospital with complaints of odynophagia and dyspnea. He underwent an emergency tracheotomy because his respiratory status rapidly worsened and tracheal intubation was impossible due to the laryngo-pharyngeal mucosal swelling. Upon admission to the hospital, a computed tomography (CT) scan revealed edematous changes in the mucosa between the oral cavity and esophagus, although perforation was not confirmed, and an upper gastrointestinal endoscope was not able to pass through the esophagus due to the severe mucosal swelling. After 40 d of conservative management with parenteral nutrition and the administration of a proton pump inhibitor, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy revealed healing of the mucosal edematous changes, and the patient was able to resume the oral intake of food. He was discharged from the hospital 53 d after admission. After discharge, the symptoms of dysphagia gradually worsened to the point that he was only able to consume liquid and jelly-like foods. He was referred to our hospital five months after the onset of dysphagia. The patient had no past medical history and no history of smoking or drinking. A laboratory analysis revealed no abnormalities in any of the parameters examined. An upper gastrointestinal endoscopy revealed a pin-hole like stricture located 19 cm distally from the incisors (Figure 1A). An esophagography revealed circumferential stenosis of the esophagus extending distally 19 cm from the incisors to the esophagogastric junction (Figure 1B). A CT scan detected circumferential stenosis and wall thickening at all levels that showed stenosis on the esophagogram (Figure 1C).

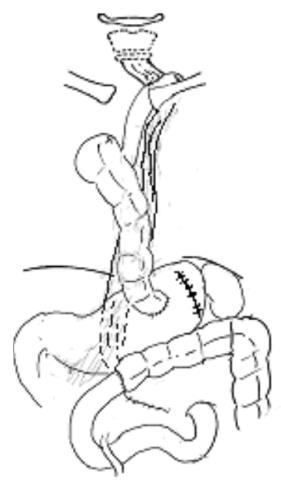

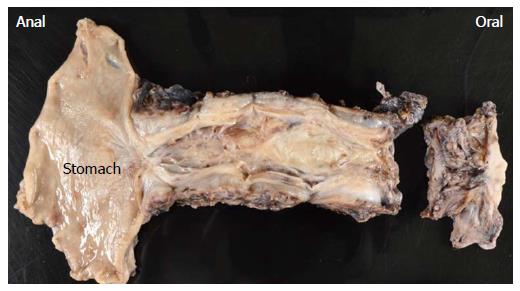

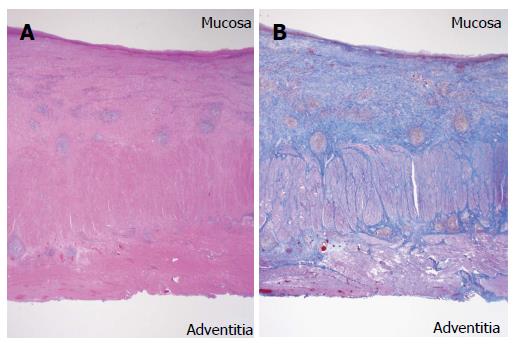

The patient was diagnosed with a benign esophageal stricture caused by thermal injury. He underwent a thoracoscopic esophageal resection with preservation of the bilateral vagus nerves, and a surgical reconstruction was performed via the retrosternal route using ileocolon interposition (Figure 2), as reported in our previous paper[11]. The intraoperative findings revealed that the esophagus was firm throughout its entire length and tightly adhered to the surrounding organs. Grossly, it was noted that the wall was thickened and had become trabeculated throughout the entire length of the resected esophagus, and the luminal area was distinctly stenosed, particularly at the esophagogastric junction (Figure 3). Histopathologically, massive fibrosis with focal infiltration of plasmacytes and lymphocytes was primarily observed in the submucosa throughout the esophagus (Figure 4A). Furthermore, the massive fibrosis extended to the muscularis propria and adventitia at almost all levels along the esophagus. The lumen was largely covered by a regenerative squamous epithelium with scattered erosion (Figure 4B).

Anastomotic leakage was not observed in the esophagogram on postoperative day (POD) 7 and the oral intake of food was resumed. However, the patient suffered from aspiration pneumonia due to transient unilateral recurrent laryngeal nerve paralysis. He restarted the oral intake of food on POD 16 and was discharged from our hospital on POD 22. After discharge, no regurgitation of gastric contents or repetitive aspiration occurred. His dysphagia significantly improved after the procedure. The patient has been able to maintain a well-balanced dietary life style with his school colleagues and has gained back the 10 kg of body weight that he had lost before the operation. As of the time of writing, the patient has been doing well for 10 months, with no evidence of complications.

Benign esophageal stricture is the result of deep esophageal injuries and is known to be induced by chemical, infectious, and physical factors, as well as other causes[1,2]. Chemical factors include gastroesophageal reflux diseases (GERD) and caustic ingestion, and infectious factors include Candida, herpes, cytomegalovirus, tuberculosis and syphilis. Physical factors involve surgery, radiation therapy and a long retention time for a nasogastric tube. Other causes include prior anastomosis and a heterogeneous group of inflammatory conditions, such as Crohn’s disease[1,2]. Thermal injury is a rare cause of benign esophageal stricture, and there have been only seven reports of esophageal acute thermal injury published in the English-language literature[2-8], according to a search of the PubMed. To perform this search, we used the following key words: “esophageal thermal injury/burn” and “thermal injury/burn of the esophagus.” Although all reported cases improved with conservative management and antisecretory treatment, such as proton pump inhibitors or histamine 2-receptor antagonists, to prevent further injury from gastric acid, the present case is the first case report of a severe esophageal stricture caused by thermal injury that required esophageal resection.

Several non-surgical options are available to treat benign esophageal stricture, including balloon dilation and stent placement. Benign esophageal stricture can be categorized as simple or complex based on the length, shape and diameter of the stricture. The present case can be classified as a complex stricture, which is defined as an area of stricture that is long (> 2 cm) or tortuous or that has a diameter that prevents the passage of an endoscope with a normal diameter[12,13]. Treatment with balloon dilation for complex strictures is generally difficult, and permanent or temporary stenting in patients with benign esophageal stricture, particularly young patients, is not widely accepted due to the incidence of late adverse events, including the development of new areas of stricture due to stent-induced granulation tissue formation, esophageal ulceration or stent migration[14-16]. Therefore, in this case, we considered surgery to be the best treatment option with respect to curability in this young patient.

In the present case, we judged resection of the esophagus to be necessary because the patient was young and there was a possibility of esophageal cancer as a late complication of esophageal thermal injury[17]. We performed an esophageal resection via video-assisted thoracic surgery rather than transhiatal esophagectomy because the wall thickness of the thoracic esophagus was circumferentially and extensively confirmed on the preoperative CT scan, and we expected that it would be technically difficult to dissect the areas of severe adhesion between the esophagus and surrounding structure.

In cases of esophageal cancer requiring reconstruction after esophagectomy, the stomach is the first choice as an esophageal substitute due to its plasticity, facility and rich submucosal vascular network[18]. Interposition with a long jejunal segment is another option; however, it can be difficult to obtain a sufficiently long jejunal segment, and the antethoracic subcutaneous route with microvascular anastomoses of intermammary vessels is often adopted, which seemed unsuitable for this young patient with benign disease. When a patient has a history of gastrectomy, concurrent gastric disease or involvement of cancer in the stomach, we use the colon instead of the stomach or jejunum. In terms of the choice of graft site in the colon, our facility prefers to use the ileocolon for several reasons[11]. Our previous report demonstrated the feasibility and favorable outcomes of colonic interposition after esophagectomy with extended lymphadenectomy in cases of esophageal cancer[11]; we therefore extended our application of ileocolon interposition to cases involving a relatively long expected prognosis due to the detection of early-stage esophageal cancer, a lack of comorbid disease or the presence of benign esophageal disease. Similarly, some studies have shown that this method is superior to gastric pull-up as an esophageal substitute in terms of the quality-of-life of esophageal cancer patients[9,10]. Long-segment colon interposition that does not include the ileal segment has been reported to provide acceptable long-term functional results in patients with benign acquired esophageal disease, such as caustic injury and gastroesophageal reflux[19]. On the other hand, Uhl et al[20] have also reported fundus rotation gastroplasty (FRG) technique after esophageal resection. Although the FRG technique allows for an increase in the remaining gastric reservoir, the reported rate of anastomotic leakage was 9.2%, which is greater than the 5.4% described in our previous report[11]. In addition, it is unlikely that the FRG technique is more effective than ileocolon interposition at preventing the regurgitation of gastric contents. Therefore, in this case, we chose ileocolon interposition reconstruction in order to preserve gastric function and improve the quality-of-life of the patient, and we preserved the bilateral vagus nerves to preserve postoperative gastric motility and pyloric function. Furthermore, the ileocolic segment, including the ileocecal valve, can prevent the reflux of gastric contents, which may cause long-standing postoperative reflux problems.

However, the long-term problems of patients who undergo ileocolon interposition remain unclear. Wain et al[19] reported that the frequency of patients with stenosed pharyngeal anastomosis due to corrosive injuries was higher than that caused by other acquired esophageal disease. Functional failure of the colonic graft has been found to be related to the severity of the initial insult, and most failures were recognized in patients who recovered nutritional autonomy more than 1 year after jejunostomy removal[21]. In addition to late failures of grafts, we should also acknowledge the possibility of certain specific types of malabsorption, such as vitamin B12 deficiency, because the terminal ileum is responsible for the selective assimilation of vitamin B12 and bile acids[22], especially in young patients. Therefore, long-term follow-up is necessary for success after ileocolon interposition in this patient.

In conclusion, this is a rare case of thermal esophageal injury that resulted in refractory esophageal stricture. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case report of thermal esophageal injury that required esophageal resection. We conclude that resection of the esophagus in patients with benign esophageal injury is a treatment option, especially in cases involving young patients with refractory esophageal stricture. In addition, performing ileocolon interposition may help to improve the quality-of-life of the patient.

A 28-year-old man with a thermal esophageal injury caused by drinking a cup of hot coffee six months earlier.

This is the first case report of thermal esophageal injury that required esophageal resection.

An upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and computed tomography revealed a pin-hole like area of stricture located 19 cm distally from the incisors to the esophagogastric junction, as well as circumferential stenosis with notable wall thickness at the same site.

The pathological findings revealed wall thickening along the entire length of the esophagus, with massive fibrosis extending to the muscularis propria and adventitia at almost all levels.

This paper illustrates is an interesting application of oesophagectomy in a relatively rare presentation of refractory oesophageal stricture. The case report is well written; outlines the necessity for the surgery; and adequately describes the choice of surgical technique and it’s appropriateness for this particular patient

P- Reviewers: Nickel F, Uttley L S- Editor: Wen LL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Lucktong TA, Morton JM, Shaheen NJ, Farrell TM. Resection of benign esophageal stricture through a minimally invasive endoscopic and transgastric approach. Am Surg. 2002;68:720-723. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Choi EK, Lee GH, Jung HY, Hong WS, Kim JH, Kim JS, Min YI. The healing course of thermal esophageal injury: a case report. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:158-160. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 13] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Javors BR, Panzer DE, Goldman IS. Acute thermal injury of the esophagus. Dysphagia. 1996;11:72-74. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Eliakim R. Thermal injury from a hamburger: a rare cause of odynophagia. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:282-283. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Go H, Yang HW, Jung SH, Park YA, Lee JY, Kim SH, Lim SH. Esophageal thermal injury by hot adlay tea. Korean J Intern Med. 2007;22:59-62. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Chung WC, Paik CN, Jung JH, Kim JD, Lee KM, Yang JM. Acute thermal injury of the esophagus from solid food: clinical course and endoscopic findings. J Korean Med Sci. 2010;25:489-491. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Dutta SK, Chung KY, Bhagavan BS. Thermal injury of the esophagus. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:480-481. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | Cohen ME, Kegel JG. Candy cocaine esophagus. Chest. 2002;121:1701-1703. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | Metzger J, Degen L, Beglinger C, von Flüe M, Harder F. Clinical outcome and quality of life after gastric and distal esophagus replacement with an ileocolon interposition. J Gastrointest Surg. 1999;3:383-388. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Metzger J, Degen L, Harder F, Von Flüe M. Subjective and functional results after replacement of the stomach with an ileocecal segment: a prospective study of 20 patients. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2002;17:268-274. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Mine S, Udagawa H, Tsutsumi K, Kinoshita Y, Ueno M, Ehara K, Haruta S. Colon interposition after esophagectomy with extended lymphadenectomy for esophageal cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;88:1647-1653. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 45] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kim JH, Shin JH, Song HY. Benign strictures of the esophagus and gastric outlet: interventional management. Korean J Radiol. 2010;11:497-506. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 30] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Siersema PD. Stenting for benign esophageal strictures. Endoscopy. 2009;41:363-373. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 63] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Cwikiel W, Willén R, Stridbeck H, Lillo-Gil R, von Holstein CS. Self-expanding stent in the treatment of benign esophageal strictures: experimental study in pigs and presentation of clinical cases. Radiology. 1993;187:667-671. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 15. | Tan BS, Kennedy C, Morgan R, Owen W, Adam A. Using uncovered metallic endoprostheses to treat recurrent benign esophageal strictures. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997;169:1281-1284. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 16. | Kim JH, Song HY, Choi EK, Kim KR, Shin JH, Lim JO. Temporary metallic stent placement in the treatment of refractory benign esophageal strictures: results and factors associated with outcome in 55 patients. Eur Radiol. 2009;19:384-390. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 79] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Muñoz N, Victora CG, Crespi M, Saul C, Braga NM, Correa P. Hot maté drinking and precancerous lesions of the oesophagus: an endoscopic survey in southern Brazil. Int J Cancer. 1987;39:708-709. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 18. | Akiyama H, Miyazono H, Tsurumaru M, Hashimoto C, Kawamura T. Use of the stomach as an esophageal substitute. Ann Surg. 1978;188:606-610. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 19. | Wain JC, Wright CD, Kuo EY, Moncure AC, Wilkins EW, Grillo HC, Mathisen DJ. Long-segment colon interposition for acquired esophageal disease. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999;67:313-317; discussion 317-318. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 20. | Uhl W, Strobel O, Friess H, Schilling M, Büchler MW. Fundus rotation gastroplasty: rationale, technique and results. Dis Esophagus. 2002;15:101-105. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 21. | Chirica M, Veyrie N, Munoz-Bongrand N, Zohar S, Halimi B, Celerier M, Cattan P, Sarfati E. Late morbidity after colon interposition for corrosive esophageal injury: risk factors, management, and outcome. A 20-years experience. Ann Surg. 2010;252:271-280. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 67] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Rampazzo A, Salgado CJ, Gharb BB, Chung TT, Mardini S, Chen HC. Necessity of Vitamin B12 replacement following free ileocolon flap transfer. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;122:153e-154e. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |