Published online Oct 7, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i37.6310

Revised: August 13, 2013

Accepted: August 28, 2013

Published online: October 7, 2013

Biliary cystadenoma (BCA) is a rare hepatic neoplasm. Although considered a benign cystic tumor of the liver, BCA has a high risk of recurrence with incomplete excision and a potential risk for malignant degeneration. Correct diagnosis and complete tumor excision with negative margins are the mainstay of treatment. Unfortunately, due to the lack of presenting symptoms, and normal laboratory results in most patients, BCA is hard to distinguish from other cystic lesions of the liver such as biliary cystadenocarcinoma, hepatic cyst, hydatid cyst, Caroli disease, undifferentiated sarcoma, intraductal papillary mucinous tumor, and hepatocellular carcinoma. Ultrasound (US), computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be necessary. They demonstrate intrahepatic cystic lesions with features such as mural nodules, varying wall thickness, papillary projections, and internal septations. Nevertheless, surgery is still the only means of accurate diagnosis. Definitive diagnosis requires histological examination following formal resection. We describe a 57-year-old woman initially diagnosed with polycystic liver who was subsequently diagnosed with giant intrahepatic BCA in the left hepatic lobe. This indicates that both US physicians and hepatobiliary specialists should attach importance to hepatic cysts, and CT or MRI should be performed for further examination when a diagnosis of BCA is suspected.

Core tip: We present a case of a 57-year-old woman who was diagnosed with polycystic liver ten years ago. She had intermittent abdominal discomfort and pain in the past 2 years. Last month, she was admitted to our hospital, and underwent exploratory laparotomy with left hepatic lobectomy, right liver cyst fenestration, and cholecystectomy. She was then diagnosed with giant biliary cystadenoma complicated with polycystic liver.

- Citation: Yang ZZ, Li Y, Liu J, Li KF, Yan YH, Xiao WD. Giant biliary cystadenoma complicated with polycystic liver: A case report. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(37): 6310-6314

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i37/6310.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i37.6310

Biliary cystadenoma (BCA) is a rare hepatic neoplasm. Although considered a benign cystic tumor of the liver, BCA has a high risk of recurrence with incomplete excision and a potential risk for malignant degeneration. Correct diagnosis and complete tumor excision with negative margins are the mainstay of treatment. Unfortunately, due to the lack of presenting symptoms, and normal laboratory results in most patients, it is hard to distinguish BCA from other cystic lesions of the liver. Definitive diagnosis requires histological examination following formal resection. We describe a 57-year-old woman initially diagnosed with polycystic liver who was subsequently diagnosed with a giant intrahepatic BCA in the left hepatic lobe. This indicates that importance should be attached to hepatic cysts in the ultrasound (US) examination, and computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) should be performed for further examination when a diagnosis of BCA is suspected.

A 57-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital with intermittent abdominal discomfort and pain for almost 2 years. Discomfort and pain were not related to meals, defecation or change in position, and could be tolerated. Initially, she underwent an US examination of the abdomen at a local hospital. This revealed multiple small cysts in the liver, which caused no particular concern. She had not experienced diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, fever or chills since the onset of symptoms. However, she noticed that her abdominal girth appeared to be slowly increasing in size 1 mo ago, and repeat US examination at an outside institution showed a left hepatic multiloculated cystic mass measuring 21.0 cm × 9.1 cm × 13.6 cm with internal septations and multiple small cysts in the left liver lobe.

She visited our hospital for further treatment. On physical examination, it was significant for abdominal tenderness and the abdomen was distended, with a large, soft, non-mobile mass in the left half of the abdomen. The patient had no history of intravenous drug use or tattoos or body piercing, no history of excessive alcohol use or obesity, and no history of working with toxic chemicals. She had no prior history of surgery, medical illness, and no known allergies. She was not using any medication. There was no significant family history of biliary or liver diseases.

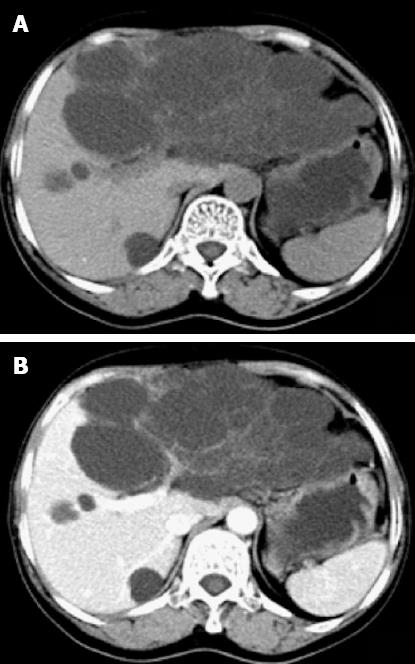

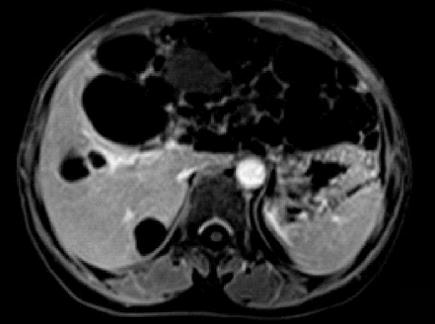

CT imaging performed at our institution demonstrated a left hepatic multiloculated cystic mass measuring 15.0 cm × 9.1 cm, occupying the majority of the upper abdomen, and normal liver structure had disappeared. The internal septations were visible and enhanced after intravenous administration of contrast medium. The mass cranially displaced the liver. The gallbladder and pancreas were compressed. Simultaneously, multiple sizes of hypoattenuating shadows without enhancement were seen in the right liver lobe (Figure 1). Abdominal MRI was ordered and revealed a large cystic tumor measuring approximately 18.0 cm × 9.0 cm originating from the left liver lobe (Figure 2). On T1-weighted imaging (T1WI), low signal intensity was apparent within the cystic spaces. On corresponding T2-weighted imaging (T2WI), the tumor was characterized by a medium-high intensity signal clearly delineated from the surrounding liver tissue with internal septal structures separating the fluid-filled spaces.

Laboratory tests were within normal limits, and serology for hepatitis B virus infection was negative, and serum carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), carbohydrate antigen (CA) 19-9, CA-125 and α-fetoprotein (AFP) levels were normal. On the basis of these findings, the patient was diagnosed with a hepatobiliary cystadenoma and polycystic liver.

The patient underwent an exploratory laparotomy with left hepatic lobectomy, right liver cyst fenestration, and cholecystectomy through a right subcostal incision. A large cystic mass presenting with grape-like blisters was located on the surface of the left lobe of the liver. It was well encapsulated and essentially without invasion into any other structures, and it was completely excised.

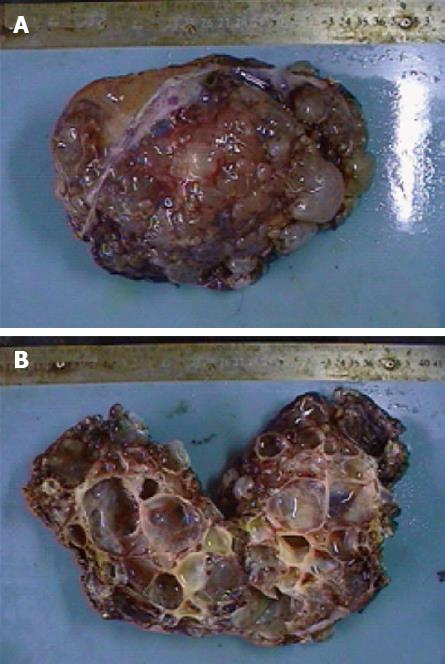

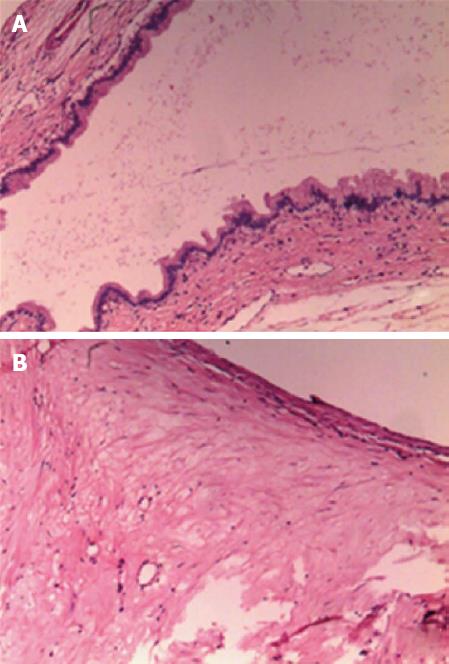

On gross examination, the resected left liver specimen showed a multilocular cystic lesion measuring 15 cm × 9 cm × 8 cm, covered with bullate nodules on the cut surface (Figure 3A). The cyst contained grayish yellow but clear fluid with no connection to the bile duct, and the wall was smooth. No masses or excrescences were noted on the inner surface (Figure 3B). Microscopically, the cystic lesion was lined by a single layer of cuboidal to columnar epithelial cells (Figure 4A). The cell morphology was normal and not pleomorphic. A stroma with proliferating fibrous tissue and a small number of inflammatory cells was underlying the epithelium (Figure 4B). Typical ovarian-like stroma was absent. The histopathology was homogeneous and uniform throughout the lesion. The surgical margins were negative and a final diagnosis of hepatobiliary cystadenoma was established. It also showed chronic inflammation of the gallbladder of the excised specimen.

The patient was seen 1 mo after surgery in the clinic. She was able to eat normally and had no abdominal discomfort. She was monitored with abdominal US for recurrence after operation. The abdominal US revealed some small cysts in the right liver lobe, whereas serological tests for CEA, CA19-9, CA-125 and AFP were within normal ranges. She was scheduled for a repeat US in 3 mo.

BCA is a cystic benign tumor which that originates from intrahepatic or extrahepatic biliary ducts, and it is also called hepatobiliary cystadenoma. BCA represents < 5% of cystic liver disease cases[1]. The cystadenoma is predominantly intrahepatic in origin and rarely seen in extrahepatic bile ducts or the gallbladder[2]. About 90% of BCAs are located intrahepatically, with a slight predilection for the right hepatic lobe. Its size varies from 3-4 cm to a giant cyst of 20-30 cm[3]. Here, we reported a giant intrahepatic BCA located in the left hepatic lobe in a 57-year-old woman.

The etiology of BCA is still unclear, although abnormal embryonic development resulting in ectopic foregut or gonadal epithelium sequestered in the liver has been proposed recently[4]. It seems that BCA has specific epidemiological characteristics. Wang et al[5] reported that the majority of intrahepatic BCA cases occurred in women aged ≤ 60 years, which was consistent with our patient’s presentation. However, 11 cases of BCA have been reported in the pediatric population[2,6,7].

Histologically, there are three described subtypes of BCA, based on the underlying type of stroma seen beneath the cuboidal or columnar epithelium. In the first subtype, BCA, microscopically, has a dense, ovarian-like mesenchymal stroma. This group is the most common and also occurs exclusively in women at a mean age of 40 years. The second subtype has non-ovarian-like stroma and is characterized by the absence of a mesenchymal layer. This group may instead have fibrous, hyaline, or myxoid stroma and is more frequently seen in men with a mean age of 50 years. The third subtype is a cystadenoma that also lacks mesenchymal stroma, but is lined by eosinophilic epithelial cells, which resemble hepatocytes. This group is rare, occurs only in men, and may be a semimalignant histological variant[6]. Our patient lacked a mesenchymal stroma but instead had fibrous stroma, and was classified into the second group.

It is difficult to make an accurate diagnosis of BCA before surgery, and to date no publication has established presenting symptoms that differentiate BCA from other benign or malignant hepatic cystic diseases such as biliary cystadenocarcinoma, hepatic cyst, hydatid cyst, Caroli disease, undifferentiated sarcoma, intraductal papillary mucinous tumor, and hepatocellular carcinoma. Patients may present with abdominal pain, abdominal distention, indigestion, nausea, vomiting, and jaundice, yet patients may be asymptomatic at presentation[8]. On physical examination, an abdominal mass can be identified occasionally. Laboratory results are normal in most patients with BCA, although serum liver enzyme and bilirubinemia levels may be mildly elevated occasionally. Serum AFP, CA19-9, CA-125 and CEA levels are usually within the normal range. It was recently reported that CA19-9 may be elevated in the cystic fluid and contributes to the diagnosis of BCA before surgery[9]. US, CT and MRI play an important role in the diagnosis and antidiastole of the disease. Medical imaging demonstrates intrahepatic cystic lesions with features such as mural nodules, varying wall thickness, papillary projections, and internal septations, which could help to distinguish BCA from other cystic lesions of the liver. On color Doppler US, BCA may appear as a multiloculated anechoic cystic structure with irregular shape and intact membranes. Dense and scattered echogenic dots can be seen in the echo-free area with partitions in between, and solid and papillary echo which is connected to the cystic wall can be seen on the partition wall. Abdominal CT scan may further characterize the multilocular cystic lesion with enhanced, thin internal septations and surrounding normal liver parenchyma, whereas the intraluminal content is usually hypoattenuating. Its fibrous capsule and internal septations are often visible and help distinguish the lesion from a simple cyst. Convex papillae can be seen on the septation, although they are more common in cystadenocarcinoma. MRI may improve tissue characterization because of its high contrast resolution. On MRI, BCA appears as a hypoattenuating lesion on T1WI and hyperintensity cystic fluid on T2WI, but the signal intensity may vary depending on the properties of the cyst fluid[10,11]. On T1WI, the signal intensity may increase with protein concentration. The signal intensity of serous fluid and bile is low. In rare cases, the intensity of serous cystic content can be raised by intracystic hemorrhage and fluid-fluid level can be present. On T2WI, septations with low signal intensity are better visualized in contrast to the high signal intensity of the cystic fluid. If jaundice is present, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatog-raphy or endoscopic retrogradecholangiopancreatography may be considered to evaluate biliary obstruction. Most commonly, displacement and extrinsic compression of the bile ducts by the tumor is seen, and rarely, communication between the cyst and biliary tree may be observed[12]. With the development of US contrast agent in recent years, contrast-enhanced ultrasonography has become increasingly useful in the diagnosis of liver lesions. BCA manifests as a non-homogeneous rich blood supply cystic masses, the solid part and the wall nodules show strong enhancement in the arterial phase, decreased enhancement in the delayed phase, and equivalent enhancement in the portal phase. Nevertheless, the wall nodules are a little more sharply enhanced in the three phases, making it difficult to differentiate from cystadenocarcinoma. It is well known that US-guided biopsy is the most commonly used method for preoperative pathological diagnosis, and cyst fluid cytology and enzymes can be detected, but carcinomatosis may occur following cyst biopsy[9].

Although imaging is the major diagnostic method for BCA at present, surgery is still the only means of accurate diagnosis. Definitive diagnosis requires histological examination following formal resection, liver transplant, or enucleation[13]. Resection or enucleation with clear margins is the treatment of choice for suspected BCA. Malignant degeneration and recurrence are 30% and 90%, respectively, for incompletely excised lesions[14]. Therefore, patients who only undergo treatment such as aspiration or laparoscopic fenestration would have a poor prognosis. Surgical resection is still necessary when there is diagnostic uncertainty, especially when the patient was complicated with simple or multiple liver cysts. Sometimes, intraoperative frozen sectioning should be performed, in order not to miss a neoplastic condition, such as cystadenocarcinoma. It is important for surgeons to determine the scope of the operation and for patients to receive timely surgery.

Our patient was complicated with polycystic liver disease, which was initially only diagnosed as polycystic liver. This indicates that such cases should be brought to the attention of US physicians and hepatobiliary specialists. In outpatients with diagnosis of hepatic cysts, especially multiple cysts, CT or MRI should be performed when a diagnosis of BCA is suspected.

P- Reviewer Giordano CR S- Editor Zhai HH L- Editor A E- Editor Zhang DN

| 1. | Harper RN, Moore MA, Marr MC, Watts LE, Hutchins PM. Arteriolar rarefaction in the conjunctiva of human essential hypertensives. Microvasc Res. 1978;16:369-372. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Devaney K, Goodman ZD, Ishak KG. Hepatobiliary cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma. A light microscopic and immunohistochemical study of 70 patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 1994;18:1078-1091. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Martínez-González J, Aicart-Ramos M, Moreira Vicente V. [Hepatic cystadenoma]. Med Clin (Barc). 2013;140:520-522. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Erdogan D, Busch OR, Rauws EA, van Delden OM, Gouma DJ, van-Gulik TM. Obstructive jaundice due to hepatobiliary cystadenoma or cystadenocarcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:5735-5738. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Wang C, Miao R, Liu H, Du X, Liu L, Lu X, Zhao H. Intrahepatic biliary cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma: an experience of 30 cases. Dig Liver Dis. 2012;44:426-431. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 39] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Senyüz OF, Numan F, Eroğlu E, Sarimurat N, Bozkurt P, Cantaşdemir M, Dervişoğlu S. Hepatobiliary mucinous cystadenoma in a child. J Pediatr Surg. 2004;39:E6-E8. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Tran S, Berman L, Wadhwani NR, Browne M. Hepatobiliary cystadenoma: a rare pediatric tumor. Pediatr Surg Int. 2013;29:841-845. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ratti F, Ferla F, Paganelli M, Cipriani F, Aldrighetti L, Ferla G. Biliary cystadenoma: short- and long-term outcome after radical hepatic resection. Updates Surg. 2012;64:13-18. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 18] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Koffron A, Rao S, Ferrario M, Abecassis M. Intrahepatic biliary cystadenoma: role of cyst fluid analysis and surgical management in the laparoscopic era. Surgery. 2004;136:926-936. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Buetow PC, Buck JL, Pantongrag-Brown L, Ros PR, Devaney K, Goodman ZD, Cruess DF. Biliary cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma: clinical-imaging-pathologic correlations with emphasis on the importance of ovarian stroma. Radiology. 1995;196:805-810. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Gabata T, Kadoya M, Matsui O, Yamashiro M, Takashima T, Mitchell DG, Nakamura Y, Takeuchi K, Nakanuma Y. Biliary cystadenoma with mesenchymal stroma of the liver: correlation between unusual MR appearance and pathologic findings. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1998;8:503-504. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 12. | Marrone G, Maggiore G, Carollo V, Sonzogni A, Luca A. Biliary cystadenoma with bile duct communication depicted on liver-specific contrast agent-enhanced MRI in a child. Pediatr Radiol. 2011;41:121-124. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 18] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Romagnoli R, Patrono D, Paraluppi G, David E, Tandoi F, Strignano P, Lupo F, Salizzoni M. Liver transplantation for symptomatic centrohepatic biliary cystadenoma. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2011;35:408-413. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Teoh AY, Ng SS, Lee KF, Lai PB. Biliary cystadenoma and other complicated cystic lesions of the liver: diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. World J Surg. 2006;30:1560-1566. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |