Published online Oct 7, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i37.6292

Revised: August 1, 2013

Accepted: August 4, 2013

Published online: October 7, 2013

Primary adult hypertrophic pyloric stenosis is a rare but important cause of gastric outlet obstruction that may be misdiagnosed as idiopathic gastroparesis. Clinically, patients present with early satiety, abdominal fullness, nausea, epigastric discomfort and eructation. Permanent gastric retention of a video capsule endoscope is diagnostic in differentiating between the two diseases, in the absence of an organic gastric outlet obstruction. This case presents the longest video capsule retention in the medical literature to date. It is also the first case report of adult hypertrophic pyloric stenosis diagnosed with video capsule endoscopy or a computed tomography scan. Finally, an unusual “plugging” of the gastric outlet with free floating capsule has an augmented effect on disease physiology and on patient’s symptoms.

Core tip: Classic descriptors and latest developments and potential role for capsule endoscopy in differential diagnosis of adult hypertrophic pyloric stenosis (HSP). First ever case of 3 years of video capsule retention in a patient. First ever report of diagnosing adult HPS with video capsule and/or with computed tomography-enterography. Physiologic effects of video capsule on symptoms in adult HPS. Differentiating between adult HPS and gastroparesis. Advances in treatment of adult HPS.

- Citation: Gurvits GE, Tan A, Volkov D. Video capsule endoscopy and CT enterography in diagnosing adult hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(37): 6292-6295

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i37/6292.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i37.6292

Video capsule endoscopy in an important tool in our ever growing arsenal in detecting bowel related abnormalities. Its wide use has lead to the significant improvement of our ability to understand and diagnose a variety of gastrointestinal (GI) diseases. Retention of the capsule is one of the feared complications of the procedure, however, its location can often point to the identifiable pathology in a patient with on obscure GI condition. In this case report, we present a truly unique situation in which a discovery of a retained capsule lead to the correct diagnosis of adult hypertrophic pyloric stenosis in a patient previously diagnosed with idiopathic gastroparesis. Interestingly, freely floating video capsule intermittently “plugged” already compromised gastric outlet, resulting in worsening of the patient’s symptoms.

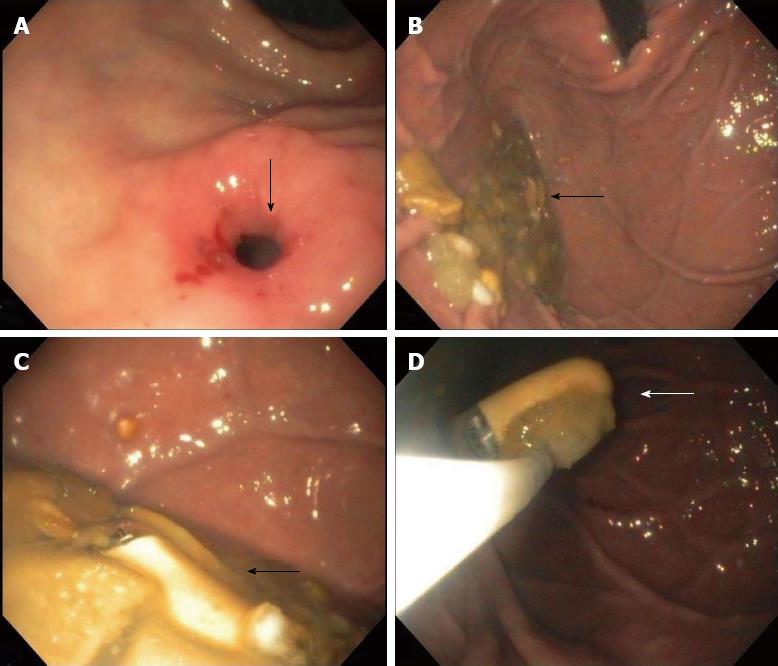

A 53-year-old female presented to our office for a second opinion evaluation of a progressive history of early satiety, weight loss, and postprandial abdominal fullness of over 10-year duration, with notable exacerbation of her symptoms over last 3 years. Her symptoms would typically worsen toward the evening. Her past medical history included depression, surgically excised breast cancer, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and eradication of Helicobacter pylori in the absence of peptic ulcer disease. Several prior esophagogastroduodenoscopies performed at different clinics were notable for persistent retention of solid food in the stomach despite overnight fasts and nuclear studies showed prolonged gastric emptying. The patient was diagnosed with gastroparesis, however, she failed to respond to trials of metoclopramide, domperidone, or erythromycin. Part of her previous work up also included a video capsule endoscopy in 2008 that commented on delayed gastric transit and an erroneous conclusion of a capsule entering small bowel after 7 h. On our initial physical exam, the patient appeared in no distress. Abdominal evaluation was unremarkable, including absence of a succession splash. Laboratory values were all within normal limits. A scout abdominal roentogram revealed a retained capsule in the gastric antrum, and a barium upper GI series demonstrated pronounced delay in gastric emptying with a narrowed slightly elongated pylorus and a distended gastric antrum (Figure 1A, B). Computed tomography (CT) enterography of the abdomen verified retained video capsule in the distended antrum of the stomach and visualized abnormally dense, eccentric, and significantly narrowed pylorus measuring 15 mm in thickness and 24 mm in length (Figure 1C). Endoscopic findings were remarkable for retained semi-digested food particles despite a two day liquid diet, and confirmed the presence of a 3-year-old video capsule freely floating in the gastric fundus. A notably fixed and narrow (7 mm pre-instrumentation) thickened pyloric channel was successfully traversed with a standard 10 mm endoscope applying moderate pressure (Figure 2). The pyloric mucosa appeared unremarkable with no mass lesion or ulceration. Evaluation of the proximal duodenum was unremarkable. Four quadrant biopsies of the pyloric channel did not reveal malignancy. The video capsule was endoscopically retrieved with a Roth Net®. The patient was diagnosed with adult hypertrophic pyloric stenosis that accounted for her symptoms. She refused possible endoscopic interventions with balloon dilation or Botox injection, and declined a surgical pyloroplasty. During follow-up at three and 6 mo, the patient appeared well and reported mild improvement in her symptoms.

Video capsule endoscopy (VCE) has revolutionized noninvasive evaluation of small intestinal mucosa since its approval for clinical use in the United States in 2001. Initially utilized for the assessment of patients with GI bleeding of obscure origin, its indications have expanded to include evaluation for small bowel tumors, polyposis syndromes, inflammatory bowel disease, and enteropathies, including celiac disease[1]. Contraindications for the study include motility disorders, obstruction, known stenotic area in the GI tract, pregnancy[2]. Today, capsule endoscopy is used in evaluation of some esophageal and colonic disorders as well.

The PillCam® capsule (Given Imaging, Yoqneam, Israel) is 11 mm in diameter and 26 mm in length. Although VCE is generally regarded as safe[3,4], capsule retention is recognized as a major complication of the procedure, potentially leading to bowel obstruction requiring its surgical removal. The 4th International Conference on Capsule Endoscopy (ICCE) in 2005 defined capsule retention as “having a capsule endoscope remain in the digestive tract for a minimum of 2 wk”. It was further defined as a “capsule remaining in the bowel lumen unless directed medical, endoscopic, or surgical intervention was instituted”[5]. The ICCE consensus did not set a time limit for removing retained capsules. In fact, asymptomatic retention and a possibility of reversing the cause of obstruction by directed medical management of the underlying condition may permit cautious non-surgical observation in select cases. Alternatively, double balloon enteroscopy may be helpful in removing retained capsule. The exact incidence of retained capsules varies widely from 0%[6] to 13%[7], depending on the indication for the study. Patients with obscure GI bleeding are considered low risk, in contrast to patients with active Crohn’s disease or suspected small bowel obstruction where higher incidence of capsule retention was noted[7,8]. Careful history taking and small bowel radiologic evaluation will lead to anticipation of a potential obstruction, and use of biodegradable patency capsule may effectively assist in its precise localization. In general, a capsule retention requiring surgical intervention occurs at a rate of 0.75%[9], ultimately leading to correct diagnosis of the underlying pathology.

Review of the medical literature to date shows that the duration of asymptomatic capsule retention varies greatly from few weeks to several years. Anatomically, the video capsule is most often retained in the ileum[5,10]. Until now, the longest reported case was 38 mo in a patient with small bowel Crohn’s disease[8]. To the best of our knowledge, our report describes the first case of a retained capsule in the stomach for over three years. It is also the first case report of adult hypertrophic pyloric stenosis diagnosed with video capsule endoscopy or a CT scan. In addition, we postulate that the physiologic worsening of our patient’s symptoms over last three years was due to the added degree of gastric flow obstruction secondary to intermittent proximal “plugging” of the pyloric channel with a retained video capsule.

Hypertrophic pyloric stenosis (HPS) is a rare cause of gastric outlet obstruction. Infantile HPS is suspected in a neonate with projectile non-bilious vomiting and weight loss, and occurs in 0.2%-0.5% of births. Classically, “olive sign” of a prominent pyloric muscle is palpated on physical examination and transabdominal ultrasound is diagnostic. Surgical intervention provides excellent prognosis. In contrast, adult HPS is a rare disorder that is further characterized as primary (idiopathic) or secondary (in association with peptic ulcer disease, malignancy, or hypertrophic gastropathy). To date, only over 200 cases of primary adult HPS have been described in the medical literature[11], although its prevalence is likely under-reported. Males are more likely to be affected, and although affected patients range from 14 to 85 years of age, it is mostly diagnosed in fourth and fifth decades of life[12]. It has been traditionally accepted that primary idiopathic adult HPS is likely a delayed presentation of a pediatric subclinical HPS. Histologically, there is marked hypertrophy and hyperplasia of the circular pyloric muscle. Grossly, pyloric channel greater than 1 cm in length and over 8 mm of muscular wall thickness is considered hypertrophic[13]. Expected diameter of normal pyloric orifice ranges from 1.2 to 1.5 cm[12]. Endoscopic findings may include “cervix sign” - a fixed narrowed pylorus with smooth borders that may preclude normal duodenal intubation with a standard gastroscope. Pyloric channel may also be eccentric in relation to the antrum with slight tenting towards lesser curvature. Upper GI series may demonstrate “Kirklin’s sign” - a mushroom-like deformity at the base of the duodenal bulb[11]. Clinically, patient may present with early satiety, abdominal fullness, nausea, epigastric discomfort and eructation. Vomiting of undigested foods may provide symptomatic improvement. Due to outlet obstruction, a gastric scintography may show delayed emptying, leading to a common misdiagnosis of gastroparesis and a delay in effective treatment. Management of symptomatic adult idiopathic HPS includes endoscopic balloon dilatation[14], surgical pyloroplasty or Billroth I or II resection[11]. Potential benefit of Botulinum toxin injection in the pyloric sphincter may be of clinical interest, although its use in HPS has never been reported.

In conclusion, we report a first case in the medical literature of idiopathic adult HPS diagnosed by unusual finding of a retained video capsule endoscope in the stomach of the patient for over 3 years. This case raises a reasonable speculation that the use of a standard patency video capsule may, in certain cases, be applied to establish a diagnosis of occult HPS, differentiating it from an idiopathic gastroparesis, in which normal pyloric opening will eventually permit passage of the capsule into the small bowel. Permanent gastric retention of an 11 mm capsule may be detected by an abdominal roentogram and the device may be easily retrieved with an endoscope. It should be also noted that, specific to primary adult HPS, as large free floating capsule follows normal food bolus propagation it may effectively block an already compromised pyloric channel proximally, thus causing transient gastric outlet obstruction and appreciable worsening of patient’s chronic symptoms. GI community should be aware of unique findings of capsule endoscopy in patients with HPS and use them to our advantage in arriving to correct diagnosis. In addition, advances in radiologic imaging have brought an important tool in CT enterography that, with better spatial resolution, may replace upper GI series as a test of choice in diagnosing primary HPS. Finally, this case raises clinical awareness of adult HPS, an uncommon medical condition that may mimic idiopathic gastroparesis, and importantly points out the need to vigilantly review antecedent workup in a complex patient with chronic GI symptoms to arrive to correct diagnosis.

P- Reviewers Dotson JL, Giles E, Refaat R S- Editor Wen LL L- Editor A E- Editor Ma S

| 1. | Karagiannis S, Faiss S, Mavrogiannis C. Capsule retention: a feared complication of wireless capsule endoscopy. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:1158-1165. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 36] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kelley SR, Lohr JM. Retained wireless video enteroscopy capsule: a case report and review of the literature. J Surg Educ. 2009;66:296-300. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Scapa E, Jacob H, Lewkowicz S, Migdal M, Gat D, Gluckhovski A, Gutmann N, Fireman Z. Initial experience of wireless-capsule endoscopy for evaluating occult gastrointestinal bleeding and suspected small bowel pathology. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2776-2779. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 193] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 208] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lewis BS, Swain P. Capsule endoscopy in the evaluation of patients with suspected small intestinal bleeding: Results of a pilot study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:349-353. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 350] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 373] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Cave D, Legnani P, de Franchis R, Lewis BS. ICCE consensus for capsule retention. Endoscopy. 2005;37:1065-1067. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 261] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 247] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Goldstein JL, Eisen GM, Lewis B, Gralnek IM, Zlotnick S, Fort JG. Video capsule endoscopy to prospectively assess small bowel injury with celecoxib, naproxen plus omeprazole, and placebo. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:133-141. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 499] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 437] [Article Influence: 23.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Cheifetz AS, Lewis BS. Capsule endoscopy retention: is it a complication? J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40:688-691. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 77] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Cheifetz AS, Kornbluth AA, Legnani P, Schmelkin I, Brown A, Lichtiger S, Lewis BS. The risk of retention of the capsule endoscope in patients with known or suspected Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2218-2222. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 258] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 251] [Article Influence: 13.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Barkin JS, Friedman S. Wireless Capsule Endoscopy requiring surgical intervention: the world’s experience. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:S298. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 107] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Cheon JH, Kim YS, Lee IS, Chang DK, Ryu JK, Lee KJ, Moon JS, Park CH, Kim JO, Shim KN. Can we predict spontaneous capsule passage after retention? A nationwide study to evaluate the incidence and clinical outcomes of capsule retention. Endoscopy. 2007;39:1046-1052. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 96] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hellan M, Lee T, Lerner T. Diagnosis and therapy of primary hypertrophic pyloric stenosis in adults: case report and review of literature. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10:265-269. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 16] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Knight CD. Hypertrophic pyloric stenosis in the adult. Ann Surg. 1961;153:899-910. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 23] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Quigley RL, Pruitt SK, Pappas TN, Akwari O. Primary hypertrophic pyloric stenosis in the adult. Arch Surg. 1990;125:1219-1221. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 15] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Yusuf TE, Brugge WR. Endoscopic therapy of benign pyloric stenosis and gastric outlet obstruction. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2006;22:570-573. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 32] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |