Published online Dec 21, 2012. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i47.6967

Revised: August 14, 2012

Accepted: August 16, 2012

Published online: December 21, 2012

AIM: To analyze sex differences in adverse drug reactions (ADR) to the immune suppressive medication in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients.

METHODS: All IBD patients attending the IBD outpatient clinic of a referral hospital were identified through the electronic diagnosis registration system. The electronic medical records of IBD patients were reviewed and the files of those patients who have used immune suppressive therapy for IBD, i.e., thiopurines, methotrexate, cyclosporine, tacrolimus and anti-tumor necrosis factor agents (anti-TNF); infliximab (IFX), adalimumab (ADA) and/or certolizumab, were further analyzed. The reported ADR to immune suppressive drugs were noted. The general definition of ADR used in clinical practice comprised the occurrence of the ADR in the temporal relationship with its disappearance upon discontinuation of the medication. Patients for whom the required information on drug use and ADR was not available in the electronic medical record and patients with only one registered contact and no further follow-up at the outpatient clinic were excluded. The difference in the incidence and type of ADR between male and female IBD patients were analyzed statistically by χ2 test.

RESULTS: In total, 1009 IBD patients were identified in the electronic diagnosis registration system. Out of these 1009 patients, 843 patients were eligible for further analysis. There were 386 males (46%), mean age 42 years (range: 16-87 years) with a mean duration of the disease of 14 years (range: 0-54 years); 578 patients with Crohn’s disease, 244 with ulcerative colitis and 21 with unclassified colitis. Seventy percent (586 pts) of patients used any kind of immune suppressive agents at a certain point of the disease course, the majority of the patients (546 pts, 65%) used thiopurines, 176 pts (21%) methotrexate, 46 pts (5%) cyclosporine and one patient tacrolimus. One third (240 pts, 28%) of patients were treated with anti-TNF, the majority of patients (227 pts, 27%) used IFX, 99 (12%) used ADA and five patients certolizumab. There were no differences between male and female patients in the use of immune suppressive agents. With regards to ADR, no differences between males and females were observed in the incidence of ADR to thiopurines, methotrexate and cyclosporine. Among 77 pts who developed ADR to one or more anti-TNF agents, significantly more females (54 pts, 39% of all anti-TNF treated women) than males (23 pts, 23% of all anti-TNF treated men) experienced ADR to an anti-TNF agent [P = 0.011; odds ratio (OR) 2.2, 95%CI 1.2-3.8]. The most frequent ADR to both anti-TNF agents, IFX and ADA, were allergic reactions (15% of all IFX users and 7% of all patients treated with ADA) and for both agents a significantly higher rate of allergic reactions in females compared with males was observed. As a result of ADR, 36 patients (15% of all patients using anti-TNF) stopped the treatment, with significantly higher stopping rate among females (27 females, 19% vs 9 males, 9%, P = 0.024).

CONCLUSION: Treatment with anti-TNF antibodies is accompanied by sexual dimorphic profile of ADR with female patients being more at risk for allergic reactions and subsequent discontinuation of the treatment.

- Citation: Zelinkova Z, Bultman E, Vogelaar L, Bouziane C, Kuipers EJ, van der Woude CJ. Sex-dimorphic adverse drug reactions to immune suppressive agents in inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18(47): 6967-6973

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v18/i47/6967.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v18.i47.6967

The existence of a sex dimorphic profile of adverse drug reactions (ADR) has been increasingly recognized in recent years. Several studies on various therapeutics pointed to differences between sexes in the incidence as well as character of ADR. In general, females seem to be more at risk for ADR to various medication, 70% of drug users with ADR in a large cohort of 2367 patients being women[1]. In addition to this generally increased risk of ADR, female patients also differ from males in terms of types of ADR to a range of medication such as antiarrhythmics, antipsychotics, anti-retroviral drugs, and analgesics[2,3].

A limited number of small size studies performed in the field of auto-immune diseases and transplant medicine suggested existence of a sexual dimorphic profile of ADR to immunosuppressive medication, but this has not been studied in depth. Male sex has been reported as a risk factor for nodular regenerative hyperplasia in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients treated with azathioprine[4]. In rheumatoid arthritis patients’ population, males have been shown to be more at risk than females for methotrexate-associated interstitial pneumonia[5] and to bacterial pneumonia complicating treatment with infliximab (IFX)[6]. For females, a higher incidence of azathioprine-related alopecia has been reported in transplant recipients[7]. In a pediatric population of Crohn’s disease (CD) patients, female sex was one of the risk factors for infusion reactions to anti-tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) treatment[8] and in an adult population of ankylosing spondylitis patients, females were more at risk of discontinuation of anti-TNF agents[9].

The sexual dimorphism of the immune responses is a generally accepted concept that has been studied predominantly in the context of the female predominance in autoimmune disorders[10] with the most important factor determining this dimorphism being the immunomodulatory properties of sex hormones. Considering these differences between the two sexes in basic immune reactions, further modulation of immune response by the immunosuppressive medication might have sex-specific consequences, including the quantitative and qualitative differences in ADR to these agents.

The limitations resulting from ADR for further therapeutic strategy in patients with chronic inflammatory conditions such as IBD are important. The ADR occurring in up to 20% of IBD patients using immune suppressive and anti-TNF agents[11,12] represent an important factor leading to the modulation or discontinuation of effective treatment. The thorough understanding of the underlying mechanism of ADR to these drugs, including the sex-related differences would help optimizing the therapy in these patients.

Therefore, in the present study we aimed to specifically determine the difference between male and female IBD patients in the occurrence and type of ADR to commonly used immunosuppressive agents, including ‘classical’ immune suppressive medication, i.e., thiopurines and methotrexate, as well as anti-TNF agents.

All IBD patients attending the outpatient clinic of the Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology of the Erasmus MC as of January 2009 were identified through the electronic diagnosis registration system. The medical records were reviewed with emphasis on details of drug treatment. Reported ADR to immune suppressive medication used for IBD were noted. Patients for whom the required information on drug use and ADR was not available in the electronic medical record and patients with only one registered contact and no further follow-up at the outpatient clinic were excluded.

All ADRs designated as such by the treating physician in the medical record were registered. The general definition of ADR used in clinical practice comprised the occurrence of the ADR in the temporal relationship with its disappearance upon discontinuation of the medication. In case of doubt about other concomitant factors contributing to the ADR a positive re-challenge was considered to be necessary for the event to be definitely categorized as ADR.

The ADR to immunosuppressive agents were divided into the following categories according to the type of symptom/event: gastro-intestinal, arthralgia and/or myalgia, cutaneous, infectious, malignancy, myelosuppresion, hepatotoxicity, or pancreatitis. In case of anti-TNF agents, additional categories of allergic reactions, lupus-like syndrome, and injection-site reactions were used.

Gastro-intestinal ADR comprised abdominal pain recognized by the patient as different from the IBD-related pain, diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting. Cutaneous ADR were defined as any kind of reported skin abnormality that occurred in temporal relationship with the treatment and resolved after cessation of the medication. Remittent or opportunistic infections occurring during the immunosuppressive treatment were noted as infectious ADR. For malignancies, any malignancy that was revealed during the use of the treatment was categorized as ADR.

Myelosuppression was defined as leucopenia (leucocytes count < 4.0 × 109/L), and/or anemia (hemoglobin level < 8.5 mmol/L for males and < 7.5 mmol/L for females) and/or thrombocytopenia (thrombocytes count < 1.5 × 1011/L). To categorize abnormal liver tests as hepatotoxic ADR, the increase of liver tests above 2 times upper normal value and absence of other causes, i.e., viral or autoimmune were required. Drug-induced pancreatitis was defined as a new abdominal pain and hyperamylasemia occurring during the treatment.

Any of the following symptoms occurring during or within one day after infusion alone or in combination were considered as allergic reactions: skin reactions, dyspnoea, chest pain, low blood pressure, angioedema, fever and/or chills. Dyspnoea, skin abnormalities and arthralgia/myalgia occurring later than two days after infusion were categorized separately as potential delayed allergic reactions. Any motoric or sensoric loss, paresthesia and/or seizures were categorized as neurological ADR. Lupus-like syndrome diagnosis was characterized as the combination of arthritis and/or flu-like symptoms or fever and presence of anti-nuclear and or anti-double strand DNA antibodies. Injection site reactions (applicable for adalimumab-ADA) were defined as pain or local skin reaction after injection.

Non-specific ADR which could not be categorized according to these criteria were analyzed together and are further referred as others.

In total, 1009 IBD patients were identified in the electronic diagnosis registration system. Out of these 1009 patients, 843 patients were eligible for analysis according to the exclusion criteria stated in the methods part. There were 386 males (46%), mean age 42 years (range: 16-87 years) with a mean duration of the disease of 14 years (range: 0-54 years); 578 patients with CD, 244 with ulcerative colitis and 21 with unclassified colitis. There were no differences between male and female patients with regard to age and disease duration; significantly more males suffered from ulcerative colitis (141 pts, 58% of all ulcerative colitis patients).

Seventy percent (586 pts) of patients used any kind of immunosuppressive agents during the disease course, the majority of the patients (546 pts, 65%) used thiopurines, 176 pts (21%) methotrexate, 46 pts (5%) cyclosporine and one patient tacrolimus. No differences between male and female patients were observed with regard to the frequency of use of immunosuppressive agents in general or of particular agent.

One third (240 pts, 28%) of patients were treated with anti-TNF, the majority of patients (227 pts, 27%) used IFX, 99 (12%) ADA and five patients certolizumab. There were no sex-related differences in the use of anti-TNF agents (Table 1).

| Males1n (%) | Females1 | P value2 | |

| Males/females (%males) | 386 (46) | 457 | |

| Age (mean, range), yr | 43 (16-87) | 42 (18-87) | 0.138 |

| Duration of the disease (mean, range) | 14 (0-48) | 14 (0-54) | 0.168 |

| CD/UC/unclassified | 233 (40)/141 (58)/12 (57) | 345/103/9 | < 0.0001 |

| Immunosuppressive agents | 265 (45) | 321 | 0.652 |

| Thiopurines | 247 (45) | 299 | 0.665 |

| Methotrexate | 73 (42) | 103 | 0.203 |

| Cyclosporine | 26 (57) | 20 | 0.170 |

| Tacrolimus | 0 | 1 | |

| Anti-TNF | 101 (42) | 139 | 0.193 |

| Infliximab | 93 (41) | 134 | 0.102 |

| Adalimumab | 39 (41) | 60 | 0.328 |

| Certolizumab | 1 (20) | 4 | 0.401 |

The sex-related differences in categorical variable were analyzed statistically using two-sided χ2 testing, for continuous variables a two-sided independent t-test was used. P-values < 0.05 were considered significant. The analysis was performed using SPSS PASW 17 software.

In total 278 patients experienced ADR to immunosuppressive agents; of which 155 patients to thiopurines (28% of all thiopurine-treated patients), 44 to methotrexate (25%), 2 (4%) to cyclosporine, and 77 pts (32%) developed ADR to one or more anti-TNF agents. As the age may represent an important factor influencing the development of ADR, a subanalysis was performed to compare the mean age between the groups of patients with and without ADR to immune suppressive agents and to anti-TNF agents. The mean age between the patients with and without ADR did not differ neither in the groups with ADR to immune suppressive agents (mean ± SEM, 41 ± 1 years in the group with ADR vs 40 ± 0.7 years in the group without ADR; P = 0.76) nor in the group with ADR to anti-TNF (mean ± SEM, 37 ± 1.5 years in the group with ADR vs 40 ± 1 year in the group without ADR to anti-TNF; P = 0.79).

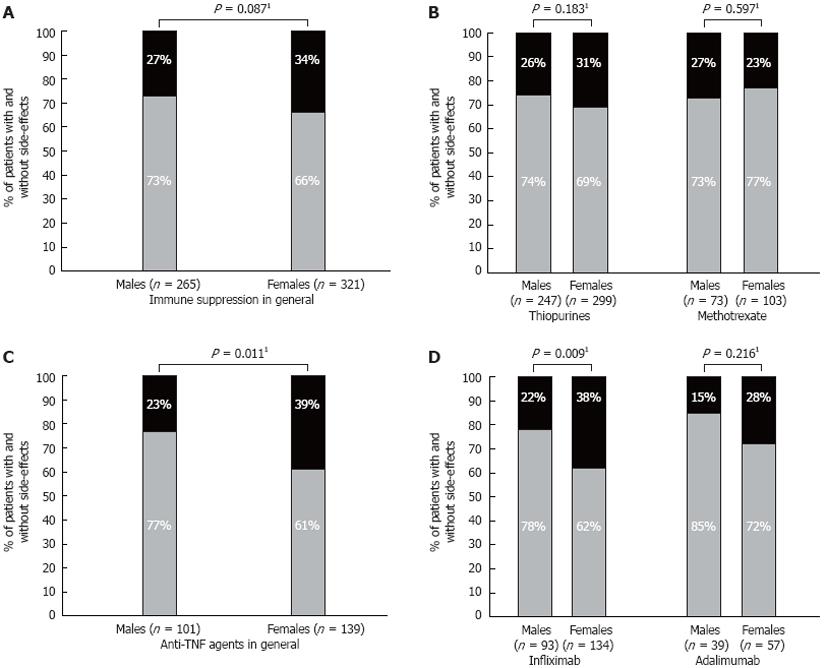

Overall, there were no significant differences in the frequencies of the ADR to immune suppressive agents between males and females. In total, 27% of males (71 pts) experienced ADR to any kind of immune suppressive agent compared to 34% of females (108 pts; P = 0.087), (Figure 1A).

Among thiopurines users, 26% of males (63 pts) and 31% of females (92 pts) suffered from ADR to thiopurines (P = 0.183; Figure 1B). The most frequent ADR to thiopurines were myelosuppression, hepatotoxicity (both in 33 pts, 6%) and gastro-intestinal ADR (23 pts, 4%), (Table 2). No differences between male and female patients were observed with regard to specific type of ADR to thiopurines.

| Thiopurines | Thiopurines1,2 | Methotrexate | Methotrexate1,2 | |

| Myelosuppression | 33 (6) | 12 (36) | NA | NA |

| Hepatotoxicity | 33 (6) | 19 (58) | 10 (6) | 6 (60) |

| Pancreatitis | 10 (2) | 2 (20) | NA | NA |

| Gastro-intestinal side-effects | 23 (4) | 8 (35) | 10 (6) | 6 (60) |

| Arthralgia and/or myalgia | 11 (2) | 5 (45) | 2 (1) | 1 (50) |

| Cutaneous side-effects | 10 (2) | 4 (40) | 3 (2) | 3 (100) |

| Infectious | 6 (1) | 3 (50) | 2 (1) | 1 (50) |

| Others3 | 23 (4) | 7 (30) | 13 (7) | 2 (15) |

| Not specified4 | 6 (1) | 3 (50) | 4 (2) | 1 (25) |

In the group of patients treated with methotrexate, 27% (20 pts) of males and 23% (24 pts) of females experienced ADR (P = 0.597; Figure 1B). The most frequent ADR to methotrexate were hepatotoxicity and gastro-intestinal ADR (both in 10 pts, 6%) (Table 2).

Out of 46 pts treated with cyclosporine, two female patients experienced an ADR, one developed pseudo-membraneus colitis following treatment but she was also treated with systemic steroids. The second patient had a cutaneous reaction to cyclosporine.

Among 77 pts who developed ADR to one or more anti-TNF agents, significantly more females (54 pts, 39% of all anti-TNF treated women) than males (23 pts, 23% of all anti-TNF treated men) experienced ADR to an anti-TNF agent [P = 0.011; odds ratio (OR) 2.2, 95%CI 1.2-3.8] (Figure 1C). In the subanalysis of respective anti-TNF agents, significantly more females (51 pts, 38% of all IFX-treated women) than males (20 pts, 22% of all IFX-treated men) suffered from ADR to IFX (P = 0.009; OR 2.2, 95%CI 1.2-4.1) (Figure 1D). Relatively more females than males experienced ADR to ADA (16 females; 28% vs 6 males; 15%), this difference was not significant though (P = 0.216) Figure 1D.

The most frequent ADR to both IFX and ADA were allergic reactions (15% of all IFX users and 7% of all patients treated with ADA) and for both agents a significantly higher rate of allergic reactions in females compared with males was observed (Table 3). There were no other sex-specific ADR observed to anti-TNF agents.

| Infliximab1 | Infliximab23 | P value2 | Adalimumab | Adalimumab23 | P value2 | |

| Allergic reaction | 33 (15) | 7 (21) | 0.045 | 7 (7) | 0 | 0.039 |

| Cutaneous SE | 9 (4) | 5 (56) | 0.492 | 3 (3) | 3 (100) | 0.064 |

| Neurological SE | 4 (1.8) | 0 | 0.146 | 2 (2) | 0 | 0.512 |

| Dyspnoea | 4 (1.8) | 0 | 0.146 | 1 (1) | 0 | 1.00 |

| Arthralgia and/or myalgia | 11 (5) | 4 (45) | 1.00 | 3 (3) | 1 (33) | 1.00 |

| Injection site reactions4 | NA | NA | 3 (3) | 1 (33) | 1.00 | |

| Infectious SE | 0 | 0 | 3 (3) | 1 (33) | 1.00 | |

| Malignancy | 16 (0.4) | 16 (100) | 0.41 | 0 | 0 | |

| Lupus-like | 1 (0.4) | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Others5 | 8 (3.5) | 2 (25) | 0.476 | 0 | 0 |

Of 77 patients experiencing ADR to an anti-TNF agent, 36 pts stopped the treatment (47%; overall discontinuation rate 15%), 27 pts (35%) switched to another anti-TNF agent, and 14 pts (18%) continued the treatment. As a result of ADR, 27 females (19% of all anti-TNF-treated women) stopped the treatment compared with 9 males (9% of all anti-TNF-treated men; P = 0.024). Furthermore, significantly higher proportion of females (21 pts, 15% of all anti-TNF-treated women) switched to another anti-TNF agents compared with males (6 pts, 6% of all anti-TNF-treated men; P = 0.026) significantly more frequently than males.

In the subanalysis of the influence of disease type and the use of immune suppression as a co-medication with anti-TNF treatment, no differences were found between the group of patients with ADR to anti-TNF compared with patients without ADR. Overall, 138 patients (58%) were on the combo therapy. Out of these 138 patients, 43 patients (31%) developed ADR to anti-TNF vs 34 patients (33%) with ADR from the group not using combo therapy (P = 0.78).

In this large retrospective study, we studied sex differences in the frequency and types of ADR to immune suppressive medication in IBD patients. In contrast to thiopurines and methotrexate with similar rates of ADR in both sexes, we observed a sex dimorphic profile of ADR to anti-TNF agents with higher frequency of ADR among female IBD patients compared with male patients. With regard to particular types of ADRs, females experienced more often allergic reactions to the most frequently used anti-TNF agents, IFX and ADA. In addition, these ADR have led to discontinuation of treatment more frequently in females than males, thus substantially limiting the long term use of anti-TNF agents by female patients.

The landmark randomized controlled trials on IFX and ADA efficacy and safety did not reveal sex dimorphic profile of ADR to anti-TNF agents[13-17]. However, the design of these studies with rather short follow-up might underestimate the overall incidence of ADR and immune-mediated ADR occurring at long term in particular. This would subsequently limit the sample size to study specific risk factors for the development of ADR. Another source of information on ADR, the safety registry with inclusion of patients being at the physicians’ discretion are difficult to interpret with regard to sex differences in ADR incidence due to the possible selection bias and also a rather short follow-up[18]. Interestingly, in a large retrospective, real-life study on long-term safety of IFX for the treatment of IBD, female sex was shown to be an independent risk factor for the development of hypersensitivity reactions and dermatological ADR to IFX[12]. In addition, one small size study with pediatric CD patients determined female sex as one of the risk factors for infusion reactions[8]. Thus, our results, in line with previous reports, suggest that female IBD patients are at specific risk for hypersensitivity reactions to monoclonal anti-TNF antibodies.

For each drug group with sex dimorphic ADR profile specific considerations for underlying mechanisms are applicable. The basic pharmacokinetic differences between the genders were at first considered to cause the predominance of ADR to some drugs in females, but over the past years, it became evident that sex hormones interacted with the particular drugs’ metabolism and mechanisms of action[3]. The sex hormones greatly influence the immune responses which might also account for the sex differences in ADR to immune system modulating therapy. However, in the present study, only biological anti-TNF agents and no other immunosuppressive treatment showed a specific ADR sex dimorphic profile. In addition, the particular ADR presenting more frequently in females were hypersensitivity reactions, suggesting a female-specific immunogenic potential related to biological therapy.

ADR to monoclonal anti-TNF antibodies have been shown to be related to the development of antibodies against these agents. Anti-infliximab as well anti-adalimumab antibodies are found in the sera of patients with loss of response and/or ADR to IFX or ADA[19-23], suggesting thus the humoral immune response as underlying mechanism of IFX- and ADA- related immunogenicity. Interestingly, some studies analyzing the sex differences in the humoral response to vaccinations showed higher antibody titers in females[24,25] and more local and systemic adverse reactions to influenza and rubella vaccines have been observed in women compared with men[26,27]. The underlying mechanism of these sex differences in humoral immune response in general is not elucidated thus far, but taken all these observational data together, it is tempting to speculate that the use of monoclonal antibodies against TNF-α might result in higher anti-anti-TNF antibodies formation rate in female patients which in turn would lead to the female-specific higher incidence of immune-mediated ADR.

This immunogenic potential of anti-TNF agents resulting in ADR has important consequences for the management of IBD patients using these drugs. In this study, up to 50% of patients experiencing ADR discontinued the treatment, with the overall discontinuation rate of all patients using anti-TNF agents being 15%. There are thus considerable potential limitations of long term use of these otherwise effective drugs. Understanding the underlying mechanisms, one of which might be female-specific immunogenicity would subsequently help to identify patients at risk and modify the therapeutic strategy accordingly.

To our knowledge, this is the first report studying the sex differences in ADR profile to immunosuppressive medication in a large cohort of patients with immune-mediated disease. The main limitation of our study is its retrospective design in which reporting bias of ADR is inevitable due to the lack of a standardized protocol that would ensure a meticulous screening of every treated patient in a prospective study design. This might particularly affect a study dealing with sex-related differences due to the psychosocial specificities of the two sexes in reporting ADRs. On the other hand, we analyzed sex-related ADRs profile to several immunosuppressive drugs in this large cohort. We found the sex dimorphism specifically applying only for anti-TNF agents and no other medication which would be the case if this reporting bias ensuing from retrospective design was substantially to modify the findings.

In conclusion, female IBD patients are at increased risk of hypersensitivity reactions to anti-TNF agents compared with males. These ADR have important clinical consequences as they lead to the discontinuation of the treatment in half of the patients experiencing these reactions. Further research, with a specific consideration of sex dimorphism of the immunogenic potential of anti-TNF agents is warranted in order to improve the clinical management of patients at risk for ADR.

Adverse drug reactions (ADR) to immune suppressive agents used for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) limit the treatment in up to 20% of patients. For various drugs, sex dimorphic profile of ADR has been documented but this has not been studied in depth in case of immune suppressive medication.

Sex has great impact on the various physiological and pathophysiological processes including pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. The immune responses differ between men and women and therefore, it is presumable that the response to immune suppressive treatment may have specific profile in male and female patients. This could specifically apply for the ADR that are immune-mediated, such as the reactions to biological therapy. With the current situation of immunogenicity of biologicals being the main limitation of this otherwise effective therapy, identifying patients with high immunogenic potential is one of the possible strategies to enhance the overall success of anti-tumor necrosis factor agents (anti-TNF) therapy.

In the present study, authors show that female IBD patients are more at risk for allergic reactions to infliximab and adalimumab compared with male patients. This sex-dimorphic profile of ADR seems to be specific to biological therapy and not a general feature of immune suppressive medication since no sex-specific ADR to thiopurines and methotrexate were observed. This increased risk for ADR to biological has been reported previously in small sample size studies of patients with various immune-mediated conditions but has not been studied as a particular phenomenon in IBD patients.

The described phenomenon of increased immunogenic potential of anti-TNF agents in females compared to males has important consequences for the management of IBD patients using these drugs. In this study, up to 50% of patients experiencing ADR to anti-TNF discontinued the treatment, with the overall discontinuation rate of all patients using anti-TNF agents being 15%. There are thus considerable potential limitations of long term use of these otherwise effective drugs. Understanding the underlying mechanisms, one of which might be female-specific immunogenicity would subsequently help to identify patients at risk and modify the therapeutic strategy accordingly.

This retrospective study in a cohort of 843 patients is aimed to specifically determine the difference between male and female IBD patients in the occurrence and type of ADR related to immunosuppressive agents (thiopurines, methotrexate, cyclosporine, tacrolimus), and anti-TNF agents (infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab). The results indicate that IBD women are at increased risk for allergic reactions in the course of anti-TNF treatment.

Peer reviewers: Pär Erik Myrelid, MD, Unit of Colorectal Surgery, Department of Surgery, Linköping University Hospital, 58185 Linköping, Sweden; Ole Haagen Nielsen, MD, DMSc, Professor, Department of Gastroenterology, D112M, Herlev Hospital, University of Copenhagen, Herlev Ringvej 75, DK-2730 Herlev, Denmark; Dr. Francesco Manguso, MD, PhD, Department of Gastroenterology, AORN A. Cardarelli, Via A. Cardarelli 9, 80122 Napoli, Italy

S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor A E- Editor Zhang DN

| 1. | Tran C, Knowles SR, Liu BA, Shear NH. Gender differences in adverse drug reactions. J Clin Pharmacol. 1998;38:1003-1009. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 138] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Franconi F, Brunelleschi S, Steardo L, Cuomo V. Gender differences in drug responses. Pharmacol Res. 2007;55:81-95. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 267] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 261] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Nicolson TJ, Mellor HR, Roberts RR. Gender differences in drug toxicity. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2010;31:108-114. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 108] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Vernier-Massouille G, Cosnes J, Lemann M, Marteau P, Reinisch W, Laharie D, Cadiot G, Bouhnik Y, De Vos M, Boureille A. Nodular regenerative hyperplasia in patients with inflammatory bowel disease treated with azathioprine. Gut. 2007;56:1404-1409. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 119] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Shidara K, Hoshi D, Inoue E, Yamada T, Nakajima A, Taniguchi A, Hara M, Momohara S, Kamatani N, Yamanaka H. Incidence of and risk factors for interstitial pneumonia in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in a large Japanese observational cohort, IORRA. Mod Rheumatol. 2010;20:280-286. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 26] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Takeuchi T, Tatsuki Y, Nogami Y, Ishiguro N, Tanaka Y, Yamanaka H, Kamatani N, Harigai M, Ryu J, Inoue K. Postmarketing surveillance of the safety profile of infliximab in 5000 Japanese patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:189-194. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 306] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 317] [Article Influence: 18.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Tricot L, Lebbé C, Pillebout E, Martinez F, Legendre C, Thervet E. Tacrolimus-induced alopecia in female kidney-pancreas transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2005;80:1546-1549. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 34] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Crandall WV, Mackner LM. Infusion reactions to infliximab in children and adolescents: frequency, outcome and a predictive model. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:75-84. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 95] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Pavelka K, Forejtová S, Stolfa J, Chroust K, Buresová L, Mann H, Vencovský J. Anti-TNF therapy of ankylosing spondylitis in clinical practice. Results from the Czech national registry ATTRA. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2009;27:958-963. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Whitacre CC. Sex differences in autoimmune disease. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:777-780. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 848] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 854] [Article Influence: 37.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Derijks LJ, Gilissen LP, Hooymans PM, Hommes DW. Review article: thiopurines in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:715-729. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 115] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Fidder H, Schnitzler F, Ferrante M, Noman M, Katsanos K, Segaert S, Henckaerts L, Van Assche G, Vermeire S, Rutgeerts P. Long-term safety of infliximab for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease: a single-centre cohort study. Gut. 2009;58:501-508. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 320] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 322] [Article Influence: 21.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Hanauer SB, Feagan BG, Lichtenstein GR, Mayer LF, Schreiber S, Colombel JF, Rachmilewitz D, Wolf DC, Olson A, Bao W. Maintenance infliximab for Crohn's disease: the ACCENT I randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;359:1541-1549. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2987] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2935] [Article Influence: 133.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hanauer SB, Sandborn WJ, Rutgeerts P, Fedorak RN, Lukas M, MacIntosh D, Panaccione R, Wolf D, Pollack P. Human anti-tumor necrosis factor monoclonal antibody (adalimumab) in Crohn's disease: the CLASSIC-I trial. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:323-333; quiz 591. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1153] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1126] [Article Influence: 62.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Rutgeerts P, Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Reinisch W, Olson A, Johanns J, Travers S, Rachmilewitz D, Hanauer SB, Lichtenstein GR. Infliximab for induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2462-2476. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2744] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2694] [Article Influence: 141.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 16. | Sandborn WJ, Hanauer SB, Rutgeerts P, Fedorak RN, Lukas M, MacIntosh DG, Panaccione R, Wolf D, Kent JD, Bittle B. Adalimumab for maintenance treatment of Crohn's disease: results of the CLASSIC II trial. Gut. 2007;56:1232-1239. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 708] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 726] [Article Influence: 42.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Sands BE, Anderson FH, Bernstein CN, Chey WY, Feagan BG, Fedorak RN, Kamm MA, Korzenik JR, Lashner BA, Onken JE. Infliximab maintenance therapy for fistulizing Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:876-885. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1581] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1473] [Article Influence: 73.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Lichtenstein GR, Feagan BG, Cohen RD, Salzberg BA, Diamond RH, Chen DM, Pritchard ML, Sandborn WJ. Serious infections and mortality in association with therapies for Crohn's disease: TREAT registry. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:621-630. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 654] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 611] [Article Influence: 33.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Bartelds GM, Wijbrandts CA, Nurmohamed MT, Stapel S, Lems WF, Aarden L, Dijkmans BA, Tak PP, Wolbink GJ. Clinical response to adalimumab: relationship to anti-adalimumab antibodies and serum adalimumab concentrations in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66:921-926. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 399] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 401] [Article Influence: 23.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Pascual-Salcedo D, Plasencia C, Ramiro S, Nuño L, Bonilla G, Nagore D, Ruiz Del Agua A, Martínez A, Aarden L, Martín-Mola E. Influence of immunogenicity on the efficacy of long-term treatment with infliximab in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2011;50:1445-1452. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 197] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 202] [Article Influence: 15.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Radstake TR, Svenson M, Eijsbouts AM, van den Hoogen FH, Enevold C, van Riel PL, Bendtzen K. Formation of antibodies against infliximab and adalimumab strongly correlates with functional drug levels and clinical responses in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:1739-1745. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 272] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 290] [Article Influence: 18.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Vultaggio A, Matucci A, Nencini F, Pratesi S, Parronchi P, Rossi O, Romagnani S, Maggi E. Anti-infliximab IgE and non-IgE antibodies and induction of infusion-related severe anaphylactic reactions. Allergy. 2010;65:657-661. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 167] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 170] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | West RL, Zelinkova Z, Wolbink GJ, Kuipers EJ, Stokkers PC, van der Woude CJ. Immunogenicity negatively influences the outcome of adalimumab treatment in Crohn's disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28:1122-1126. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 134] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Chen XQ, Bülbül M, de Gast GC, van Loon AM, Nalin DR, van Hattum J. Immunogenicity of two versus three injections of inactivated hepatitis A vaccine in adults. J Hepatol. 1997;26:260-264. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 32] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Chiaramonte M, Majori S, Ngatchu T, Moschen ME, Baldo V, Renzulli G, Simoncello I, Rocco S, Bertin T, Naccarato R. Two different dosages of yeast derived recombinant hepatitis B vaccines: a comparison of immunogenicity. Vaccine. 1996;14:135-137. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 23] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Benjamin CM, Chew GC, Silman AJ. Joint and limb symptoms in children after immunisation with measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine. BMJ. 1992;304:1075-1078. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 50] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Govaert TM, Dinant GJ, Aretz K, Masurel N, Sprenger MJ, Knottnerus JA. Adverse reactions to influenza vaccine in elderly people: randomised double blind placebo controlled trial. BMJ. 1993;307:988-990. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 141] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |