Published online Nov 14, 2011. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i42.4682

Revised: December 1, 2010

Accepted: December 8, 2010

Published online: November 14, 2011

AIM: To evaluate the accuracy of two non-invasive tests in a population of Alaska Native persons. High rates of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection, H. pylori treatment failure, and gastric cancer in this population necessitate documentation of infection status at multiple time points over a patient’s life.

METHODS: In 280 patients undergoing endoscopy, H. pylori was diagnosed by culture, histology, rapid urease test, 13C urea breath test (UBT), and immunoglobulin G antibodies to H. pylori in serum. The performances of 13C-UBT and antibody test were compared to a gold standard defined by a positive H. pylori test by culture or, in case of a negative culture result, by positive histology and a positive rapid urease test.

RESULTS: The sensitivity and specificity of the 13C-UBT were 93% and 88%, respectively, relative to the gold standard. The antibody test had an equivalent sensitivity of 93% with a reduced specificity of 68%. The false positive results for the antibody test were associated with previous treatment for an H. pylori infection [relative risk (RR) = 2.8]. High levels of antibodies to H. pylori were associated with chronic gastritis and male gender, while high scores in the 13C-UBT test were associated with older age and with the H. pylori bacteria load on histological examination (RR = 4.4).

CONCLUSION: The 13C-UBT outperformed the antibody test for H. pylori and could be used when a non-invasive test is clinically necessary to document treatment outcome or when monitoring for reinfection.

-

Citation: Bruden DL, Bruce MG, Miernyk KM, Morris J, Hurlburt D, Hennessy TW, Peters H, Sacco F, Parkinson AJ, McMahon BJ. Diagnostic accuracy of tests for

Helicobacter pylori in an Alaska Native population. World J Gastroenterol 2011; 17(42): 4682-4688 - URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v17/i42/4682.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v17.i42.4682

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection has been associ-ated with peptic ulcer disease, gastric cancer, and acute gastritis[1]. Alaska Native persons have a high sero-prevalence of H. pylori (75% all ages)[2], along with high rates of gastric cancer[3]. In rural Alaska, H. pylori seroprevalence is as high as 69% by the ages of 5-9 years and 87% among 7-11 year olds, as measured by the urea breath test (UBT)[4]. These findings have led to research investigations on H. pylori treatment outcome, reinfection rates after treatment, and the association of H. pylori infection with anemia in this population[4-8]. In Alaska, antimicrobial resistance rates in H. pylori are as high as 63% for metronidazole, 31% for clarithromycin, and 9% for levofloxacin[5,9,10]. Along with high levels of antimicrobial resistance, treatment failure rates approaching 30% in urban Alaska and 45% in rural Alaska have been demonstrated. The rate of H. pylori reinfection in Alaskan adults after two years was 14.5%[6]. In rural Alaskan children, aged 7 to 11 years, the reinfection rate exceeded 50% 32 mo after documented successful treatment[11].Tests are needed after esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) to document cure and continued infection-free status because of high rates of treatment failure and reinfection for H. pylori. Tests dependent on an EGD are not feasible for sequential follow-up or for longitudinal research studies. In rural and remote study populations, EGD testing is not available. Additionally, the cost and invasiveness of an EGD make H. pylori tests that are dependent upon them impractical in some settings.

This investigation was conducted as part of an Alaskan H. pylori reinfection study in which we enrolled persons scheduled for EGD over a three year period, treated them for H. pylori, and then followed them for two years with the 13C-UBT test. As part of a secondary objective, we enrolled persons both positive and negative for H. pylori infection who were undergoing EGD for clinical indications. We aimed to determine the accuracy of non-invasive H. pylori tests compared to the invasive gold standard tests, based on samples obtained during EGD. The non-invasive tests that were considered in this evaluation were the 13C-UBT and the detection of immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies to H. pylori (anti-HP) in serum. The invasive tests evaluated in this study were culture, histology and rapid urease test [campylobacter-like organism (CLO) test®]. We also sought to determine if the performance of the 13C-UBT and the antibody assay could be improved through use of different cut-off points. Additionally, we examined whether the quantitative level of anti-HP or the 13C-UBT were associated with clinical characteristics of the H. pylori infection, such as the presence of a peptic ulcer and the severity of gastritis, in this Alaskan population.

Persons ≥ 18 years of age undergoing EGD for clinical indications at the Alaska Native Medical Center (ANMC) in Anchorage, Alaska gave their consent to participate in an H. pylori reinfection study between September 1998 and December 2000. A description of this study cohort has been previously published[6]. From this cohort, we conducted a cross-sectional analysis to determine the sensitivity and specificity of five tests for H. pylori: serology, culture, CLO test® (Ballard Medical Products, Draper, UT, United States), histology and 13C urea breath test (BreathTekTM UBT; Meretek Diagnostics Inc., Lafayette, CO, United States). The result of the breath test is measured as the delta over baseline (DOB), which is the difference between the ratio 13CO2/12CO2 after and before consumption of a Pranactin-Citric solution containing 13C-urea. The participants were recruited prior to EGD; therefore, the cohort consisted of persons both positive and negative for H. pylori. Upon enrollment, a medical chart review was performed at ANMC to determine the participants’ history of: peptic ulcer disease, previous EGD procedures, and previous treatment for an H. pylori infection. Endoscopic findings documented during EGD included location and type of ulcer and presence of antral and fundal gastritis.

This study was approved by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Institution Review Board (IRB), the Alaska Area IRB of the Indian Health Service, the Southcentral Foundation Board, as well as the Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium Board of Directors. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

At the time of EGD (initial enrollment), blood was drawn and a 13C-UBT test was administered. Sera were tested for H. pylori-specific IgG by an in-house enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), as described previously[7]. Sera were negative if the optical density (OD) was ≤ 0.3, positive if ≥ 0.5, and indeterminate if in between. In-house ELISA cut-offs were determined using 254 sera collected from a previous study[7].

All participants had up to three gastric biopsy specimens taken for testing for H. pylori from the antrum and the fundus of the stomach. One biopsy was taken, as per the manufacturer’s instructions for the CLO test®, for the detection of urease. Biopsies were stained with Diff-Quik® (Mercedes Medical, Sarasota, FL, United States) stain, for identification of H. pylori, and with hematoxylin and eosin stain for histological evaluation. A research pathologist examined both histological slides for the presence of intestinal metaplasia, acute and chronic gastritis, and the amount of H. pylori present, according to the Updated Sydney System[12]. The final one or two biopsies were used to culture H. pylori. Cultures were incubated at 37 °C, 12% CO2, and 98% humidity for up to 10 d. Isolates were identified as H. pylori on the basis of positive catalase, oxidase, and urease reactions, typical colony morphology, and curved gram-negative bacilli on gram-stained smears.

The gold standard used to compare test accuracies was a positive result by culture or in the case of a negative culture, a positive result by both histology and CLO test®. Test accuracy was the number of true positives plus true negatives divided by the total sample size. The manufacturer’s recommended cut-off (DOB ≥ 2.4) for the 13C-UBT test was used for definition of a positive H. pylori result for analysis.

The characteristics of the 280 patients who underwent EGD are shown in Table 1. The mean age of participants was 48 years and 66% were female. Of the 280 participants, 155 (55%) were positive by the 13C-UBT test (Table 2). Ninety-two persons tested positive for anti-HP IgG (OD value ≥ 0.5), 168 persons tested negative (OD value ≤ 0.3), and 20 were indeterminate. If persons with indeterminate results by the antibody test are considered negative for H. pylori infection, then 60% of the entire 280 persons were positive by serology (Table 2). However, if those with indeterminate results were removed, then 65% were positive for H. pylori antibodies (Table 2). Of the 280 participants, 50%, 51% and 49% of persons were positive for H. pylori by histology, culture and CLO test®, respectively. Using the gold standard of either a positive culture, or a positive result of both histology and CLO test®, 53% (149/280) of persons were positive for H. pylori.

| Characteristic | % (n) |

| Mean age (min, max) | 48 yr (19, 88) |

| Sex (female) | 66% (184) |

| Medical chart review | |

| History of peptic ulcer disease | 19% (53) |

| Previous EGD | 32% (90) |

| Previously treated for H. pylori | 23% (63) |

| Endoscopist evaluation during EGD | |

| Moderate-severe gastritis | 41% (115) |

| Mild-no gastritis | 59% (165) |

| Ulcer | 9% (25) |

| Test type | % H. pyloripositive (n/N) | |

| Histology | Antrum | 49% (135/278) |

| Fundus | 46% (124/271) | |

| Combined | 50% (140/280) | |

| Culture | Antrum | 48% (133/275) |

| Fundus | 50% (136/273) | |

| Combined | 51% (144/280) | |

| CLO test®1 | 49% (138/280) | |

| Gold standard2 | 53% (149/280) | |

| 13C-UBT3 | 55% (155/280) | |

| Anti-HP IgG | Indeterminates considered negative | 60% (168/280) |

| Indeterminates considered positive | 67% (188/280) | |

| Indeterminates removed | 65% (168/260) |

The performance of the non-invasive tests in comparison to the invasive tests and the gold standard are shown in Table 3. The sensitivity of the 13C-UBT test in relationship to invasive tests and the gold standard ranged from 93% to 97%. The specificity was somewhat lower, and ranged from 78% to 88% when compared against invasive tests and the gold standard. The accuracy of the 13C-UBT test ranged from 86% to 90%. The sensitivity of the serological assay (detection of anti-HP) in relation to the invasive tests and the gold standard was between 92% and 93%, and the specificity ranged from 58% to 68%. The concordance of anti-HP and 13C-UBT was 81%. For the two invasive tests of histology and culture, there was concordance on 89% of persons. Finally, the CLO test® had a concordance of 90% and 92% with respect to histology and culture, respectively.

| Test type 1 | Test type 2 | Sensitivity | Specificity | NPV2 | PPV2 | Accuracy |

| 13C-UBT3vs | Histology | 93.6% (131/140) | 82.9% (116/140) | 92.8% (116/125) | 84.5% (131/155) | 88.2% (247/280) |

| Histology and CLO test®4 | 96.8% (121/125) | 78.1% (121/155) | 96.8% (121/125) | 78.1% (121/155) | 86.4% (242/280) | |

| Culture | 93.1% (134/144) | 84.6% (115/136) | 92.0% (115/125) | 86.5% (134/155) | 89.0% (249/280) | |

| Culture and CLO test® | 94.6% (123/130) | 78.7% (118/150) | 94.4% (118/125) | 79.4% (123/155) | 86.1% (241/280) | |

| Gold standard | 93.3% (139/149) | 87.8% (115/131) | 92.0% (115/125) | 89.7% (139/155) | 90.7% (254/280) | |

| Anti-HP IgG vs | Histology | 91.5% (118/129) | 61.8% (81/131) | 88.0% (81/92) | 70.2% (118/168) | 76.5% (199/260) |

| Histology and CLO test® | 93.1% (108/116) | 58.3% (84/144) | 91.3% (84/92) | 64.3% (108/168) | 73.8% (192/260) | |

| Culture | 93.3% (126/135) | 66.4% (83/125) | 90.2% (83/92) | 75.0% (126/168) | 80.3% (209/260) | |

| Culture and CLO test® | 93.4% (113/121) | 60.4% (84/139) | 91.3% (84/92) | 67.3% (113/168) | 75.8% (197/260) | |

| Gold standard | 92.9% (130/140) | 68.3% (82/120) | 89.1% (82/92) | 77.4% (130/168) | 81.5% (212/260) | |

| Anti-HP IgG vs | 13C-UBT | 91.0% (131/144) | 68.1% (79/116) | 85.9% (79//92) | 78.0% (131/168) | 80.8% (210/260) |

| Histology vs | Culture | 87.5% (126/144) | 89.7% (122/136) | 87.1% (122/140) | 90.0% (126/140) | 88.6% (248/280) |

| CLO test®vs | Histology | 89.3% (125/140) | 90.7% (127/140) | 89.4% (127/142) | 90.6% (125/138) | 90.1% (252/280) |

| CLO test®vs | Culture | 90.3% (130/144) | 94.1% (128/136) | 90.1% (128/142) | 94.2% (130/138) | 92.1% (258/280) |

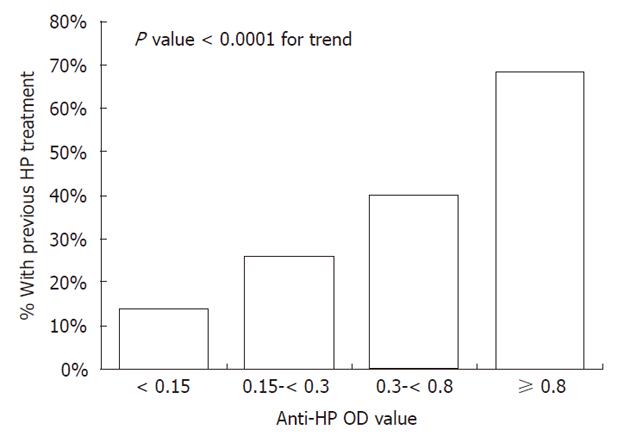

The sensitivity and specificity of the anti-HP assay presented in Table 3 were calculated with the indeterminate (0.3 ≤ anti-HP OD < 0.5) results removed. The overall accuracy of the anti-HP assay against the gold standard was 81.5%. Of 118 persons negative for H. pylori by the gold standard, 32% (n = 38) were positive by anti-HP (representing the false positives) and 68% (n = 80) were negative by anti-HP. In these 118 persons, 55% (21/38) of persons positive by anti-HP had a previous treatment for H. pylori documented in their medical record compared to 20% (16/80) of persons negative for anti-HP [relative risk (RR) = 2.8, 95% CI: 1.6-4.7]. In these 118 persons, the magnitude of the anti-HP OD was positively associated with previous treatment for H. pylori (P < 0.0001, Figure 1). Persons with an anti-HP OD ≥ 0.8 were 4.9 times (95% CI: 2.1-11.7) more likely to have had a previous treatment for H. pylori than persons with an anti-HP OD < 0.15.

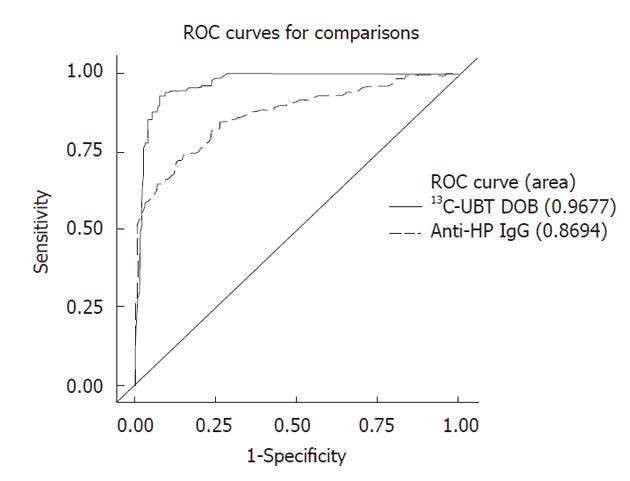

The receiver operating curves for the quantitative anti-HP OD measurements against the gold standard are shown in Figure 2, with indeterminate results included (n = 280). The accuracy of the serological assay was between 78%-80% for cut-off points between anti-HP OD values of 0.3 and 0.7. The accuracy of the serological test diminishes using cut-off points above an anti-HP OD value of 0.7. The sensitivity and specificity of the anti-HP assay at a cut-off point of 0.3 are 94% and 61%, respectively. At a higher cut-off point of 0.7, the specificity of the test improves to 82%, but the sensitivity decreases from 94% to 76%. At no cut-off point does the accuracy of the anti-HP assay exceed 80% when the indeterminate results are included. The optimal cut-off point when including the indeterminate results was an anti-HP OD value of 0.5, which resulted in a test accuracy of 79.6%. A high anti-HP OD among persons positive for H. pylori by the gold standard was associated with male gender and chronic gastritis on histological examination (Table 4). The association with chronic gastritis was stronger in the antral specimen (P = 0.02) than the fundal specimen (P = 0.25).

| Factors | Anti-HP IgG OD1 | 13C-UBT DOB2 | ||||

| High, OD≥1.1, (n = 76) | Low, OD < 1.1, (n = 73) | P value | High,≥10%, (n = 71) | Low, < 10%, (n = 78) | P value | |

| Demographics | ||||||

| % Male | 54% (41) | 19% (14) | < 0.0001 | 31% (22) | 42% (33) | 0.15 |

| % ≥ 50 years of age | 33% (25) | 40% (29) | 0.39 | 53% (27) | 29% (27) | 0.002 |

| Factors from histological examination | ||||||

| % Intestinal metaplasia | 11% (8) | 12% (9) | 0.73 | 8% (6) | 14% (11) | 0.27 |

| % Acute gastritis | 55% (42) | 49% (36) | 0.47 | 49% (35) | 55% (43) | 0.48 |

| % Chronic gastritis | 93% (71) | 77% (56) | 0.003 | 86% (61) | 85% (66) | 0.82 |

| % Numerous H. pylori | 42% (32) | 36% (26) | 0.42 | 54% (38) | 26% (20) | 0.0005 |

| Endoscopic factors | ||||||

| % Ulcer | 10% (7) | 11% (8) | 0.76 | 9% (6) | 12% (9) | 0.57 |

| % Gastritis | 58% (42) | 40% (29) | 0.03 | 49% (34) | 48% (37) | 0.88 |

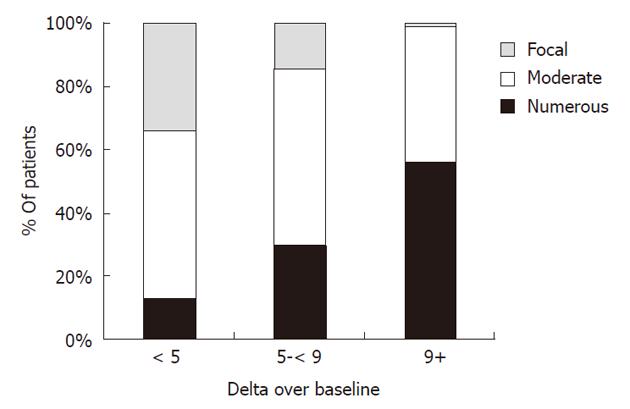

The overall accuracy of the 13C-UBT test against the gold standard was 91%, with an area under the curve value of 0.97 (Figure 2). The accuracy of the 13C-UBT test was above 90% for all values in between a DOB of 2.0 and 4.0 and was highest, at 93%, between 2.8 and 3.0. Using a lower value of 2.0 as the cut-off point (91% accuracy) resulted in false negative and positive rates of 5% and 12%, whereas use of a higher value of 4.0 (90% accuracy) resulted in false negative and positive rates of 15% and 5%, respectively. The 13C-UBT had a specificity and positive predictive value of 100% for cut-offs ≥ 7.0 DOB. Additionally, among persons positive for H. pylori by the gold standard, a high 13C-UBT DOB was associated with the number of H. pylori organisms seen on histological slides and age ≥ 50 years (Table 4). Persons with a 13C-UBT ≥ 9 DOB were 4.4 (95% CI: 1.7-11.3) times more likely to have a large number of H. pylori bacteria on histological examination than persons with a 13C-UBT < 9 DOB (Figure 3).

Our study provides important information about the accuracy of five tests commonly used in clinical practice for the diagnosis of H. pylori infection. Clinicians have a variety of tests to choose from to diagnose H. pylori infection in patients with abdominal symptoms. The data comparing the sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of each test are incomplete and can be confusing to clinicians. We evaluated the performance of H. pylori tests in a population of Alaskan native adults with a high prevalence of H. pylori infection (53% using the gold standard). The 13C-UBT test accurately diagnosed 91% of persons relative to our gold standard, whereas the serological assay had a reduced accuracy of 81%. Our study suggests that in populations with high rates of sequelae from H. pylori (gastric cancer, duodenal ulcer disease), as well as high H. pylori treatment failure rates, and high reinfection rates after treatment, the 13C-UBT test may be the best non-invasive test option available for longitudinal evaluation of H. pylori infection.

The antibody assay had low specificity and positive predictive value because this test can be positive in persons with a previous successfully treated H. pylori infection and in those with a current active infection. In this study population of urban Alaska Native adults evaluated by EGD, over 1 in 5 persons were found to have had a treatment for H. pylori documented in their medical records prior to entering the study. We found some persons who were negative by the gold standard tests for active infection, among whom we were able to document that the presence of anti-HP IgG was associated with previous treatment for H. pylori. Indeed in this group, persons with a high level anti-HP IgG were close to five times more likely to have been previously treated for H. pylori compared to those with low levels of anti-HP. Previously published data from this study found that the mean anti-HP IgG level was 0.64 OD units (above the assay’s positive breakpoint) two years after documented successful treatment for H. pylori[7] , demonstrating that anti-HP antibodies persist long after eradication. The antibody assay may still be suitable in treatment naïve populations in epidemiological investigations aimed at establishing baseline estimates of H. pylori prevalence. However, for the clinical purpose of identifying persons with active H. pylori infection, the antibody test has limited utility, because persons recovered from H. pylori infection might be mistakenly identified as harboring an active infection. In populations with a high prevalence of, and treatment for H. pylori infection, this assay is not optimal for use in a “test and treat” strategy in patients with dyspeptic symptoms. Patients identified by elevated antibody levels who are not actively infected may unnecessarily receive additional treatment for H. pylori.

We found that the anti-HP OD ≥ 1.1 was associated with male gender and chronic gastritis as determined by histological evaluation. The finding of an association with gastritis has been documented in other studies[13-16]. Sheu et al[13] found the titer level of H. pylori to be associated with antral gastritis but not presence of ulcer, similar to our study. In contrast, Chen et al[17] did not find an association with antral gastritis when restricting the analysis to H. pylori positive persons, an analysis similar to ours. Although the serological assay is less accurate in predicting active H. pylori infection in this Alaska Native population, high levels of anti-HP IgG increased the odds by 4-fold that chronic gastritis will be diagnosed by histology. The lower anti-HP level found in women could be attributable to inadvertent treatment of the H. pylori infection in the use of metronidazole for treating vaginal infections in women. Indeed, in this study group, women had higher levels of metronidazole use[8], and higher levels of metronidazole use were associated with lower anti-HP levels (CDC unpublished data).

With a sensitivity and specificity of 93% and 97%, respectively, using the manufacturer’s recommended cut-off point, the 13C-UBT provided the best non-invasive test for documentation of infection-free status. The accuracy of the test in our population compares well with performance of the UBT (both 13C-UBT and 14C-UBT) in other studies[18-20], and is in contrast to a recent study that found much lower specificity in Spain[21]. In our study, we found that the accuracy of the 13C-UBT was > 90% with cut-off points between 2.0 and 4.0 DOB, similar to findings in other reports[22]. Additionally, we found that the DOB value was positively associated with the amount of H. pylori present on histological examination. Persons with very high DOB values were over four times more likely to have a high concentration of H. pylori bacteria than persons with low DOB values, an association documented elsewhere[23-25]. The association between the concentration of H. pylori organisms on histology and other pathological outcomes (gastritis, intestinal metaplasia), as well as treatment outcome, is being investigated further.

In summary, in a population in the United States with a high background prevalence of H. pylori, we found that the 13C-UBT test outperforms the serological assay in the detection of active H. pylori infection. The 13C-UBT avoids the problem associated with the serological test of incorrectly identifying persons who have recovered from H. pylori as having active infection. For clinical purposes, in persons with gastrointestinal symptoms in whom an EGD procedure is not planned, the 13C-UBT appears to be useful to rule out or confirm H. pylori infection, and to test for a cure in persons who have been treated for H. pylori infection.

The authors would like to thank Catherine Dentinger, Marilyn Getty, Jim Gove, Cindy Hamlin and Susan Seidel for patient recruitment.

High rates of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection and antimicrobial resistance have been documented in Alaska Native persons. High infection pressure and antimicrobial resistance have led to elevated rates of treatment failure of and reinfection with H. pylori. Non-invasive tests, not dependent on an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD), are necessary to document cure and continued infection-free status.

The performances of five tests [13C urea breath test (UBT), detection of immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies to H. pylori in serum, culture, histology and rapid urease test] that are commonly used in clinical practice for H. pylori were evaluated in 280 patients undergoing EGD at the Alaska Native Medical Center in Anchorage, Alaska.

The overall accuracy for diagnosing H. pylori infection was 91% for the 13C-UBT test and 81% for the antibody assay. False positive results for the antibody assay were associated with previous successful treatment of H. pylori infection. A high antibody level was associated with histological gastritis. An elevated level for the 13C-UBT test was associated with a high bacterial load of H. pylori on histological examination.

In a population with a high background rate of H. pylori infection, the authors found the 13C-UBT to be the most clinically useful noninvasive test for the diagnosis and follow-up of patients with gastrointestinal symptoms.

The result of the 13C-UBT test is measured as the delta over baseline, which is the difference between the ratio 13CO2/12CO2 after and before the consumption of a Pranactin-Citric solution containing 13C-urea. Test accuracy was the number of true positives plus true negatives divided by the total sample size.

This study is a well-done population study for the evaluation of the accuracy of two non-invasive tests (13C-UBT) and the detection of IgG antibodies to H. pylori in serum) in a population of Alaska Native persons with high prevalence of H. pylori infection.

Peer reviewer: Dr. Tamara Vorobjova, Senior Researcher in Immunology, Department of Immunology, Institute of General and Molecular Pathology, University of Tartu, Ravila, 19, Tartu 51014, Estonia

S- Editor Yang XC L- Editor Stewart GJ E- Editor Li JY

| 1. | Kusters JG, van Vliet AH, Kuipers EJ. Pathogenesis of Helicobacter pylori infection. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19:449-490. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1446] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1411] [Article Influence: 78.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Parkinson AJ, Gold BD, Bulkow L, Wainwright RB, Swaminathan B, Khanna B, Petersen KM, Fitzgerald MA. High prevalence of Helicobacter pylori in the Alaska native population and association with low serum ferritin levels in young adults. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2000;7:885-888. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Lanier AP, Kelly JJ, Maxwell J, McEvoy T, Homan C. Cancer in Alaska Native people, 1969-2003. Alaska Med. 2006;48:30-59. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Gessner BD, Baggett HC, Muth PT, Dunaway E, Gold BD, Feng Z, Parkinson AJ. A controlled, household-randomized, open-label trial of the effect that treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection has on iron deficiency in children in rural Alaska. J Infect Dis. 2006;193:537-546. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 52] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Bruce M, McMahon BJ, Hennessy TW. The relationship between antimicrobial resistance and treatment outcome for H. pylori infections in Alaska Native and non-Native Persons residing in Alaska. Gastroenterol. 2005;128:T944. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | McMahon BJ, Bruce MG, Hennessy TW, Bruden DL, Sacco F, Peters H, Hurlburt DA, Morris JM, Reasonover AL, Dailide G. Reinfection after successful eradication of Helicobacter pylori: a 2-year prospective study in Alaska Natives. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:1215-1223. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 32] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Miernyk KM, Bruden DL, Bruce MG, McMahon BJ, Hennessy TW, Peters HV, Hurlburt DA, Sacco F, Parkinson AJ. Dynamics of Helicobacter pylori-specific immunoglobulin G for 2 years after successful eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection in an American Indian and Alaska Native population. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2007;14:85-86. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 13] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | McMahon BJ, Hennessy TW, Bensler JM, Bruden DL, Parkinson AJ, Morris JM, Reasonover AL, Hurlburt DA, Bruce MG, Sacco F. The Relationship among Previous Antimicrobial Use, Antimicrobial Resistance, and Treatment Outcomes for Helicobacter pylori Infections. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2003;139:463-469. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | Bruce MG, Bruden DL, McMahon BJ, Hennessy TW, Reasonover A, Morris J, Hurlburt DA, Peters H, Sacco F, Martinez P. Alaska sentinel surveillance for antimicrobial resistance in Helicobacter pylori isolates from Alaska native persons, 1999-2003. Helicobacter. 2006;11:581-588. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 27] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Carothers JJ, Bruce MG, Hennessy TW, Bensler M, Morris JM, Reasonover AL, Hurlburt DA, Parkinson AJ, Coleman JM, McMahon BJ. The relationship between previous fluoroquinolone use and levofloxacin resistance in Helicobacter pylori infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:e5-e8. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 68] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Fagan RP, Dunaway CE, Bruden DL, Parkinson AJ, Gessner BD. Controlled, household-randomized, open-label trial of the effect of treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection on iron deficiency among children in rural Alaska: results at 40 months. J Infect Dis. 2009;199:652-660. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 33] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Dixon MF, Genta RM, Yardley JH, Correa P. Classification and grading of gastritis. The updated Sydney System. International Workshop on the Histopathology of Gastritis, Houston 1994. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20:1161-1181. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 3221] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 3366] [Article Influence: 120.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 13. | Sheu BS, Shiesh SC, Yang HB, Su IJ, Chen CY, Lin XZ. Implications of Helicobacter pylori serological titer for the histological severity of antral gastritis. Endoscopy. 1997;29:27-30. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 24] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Yamamoto I, Fukuda Y, Mizuta T, Fukada M, Nishigami T, Shimoyama T. Serum anti-Helicobacter pylori antibodies and gastritis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1995;21 Suppl 1:S164-S168. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 15. | Nakata H, Itoh H, Yokoya Y, Kawai J, Nishioka S, Miyamoto K, Kitamoto N, Miyamoto H, Tanaka T. Serum antibody against Helicobacter pylori assayed by a new capture ELISA. J Gastroenterol. 1995;30:295-300. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kreuning J, Lindeman J, Biemond I, Lamers CB. Relation between IgG and IgA antibody titres against Helicobacter pylori in serum and severity of gastritis in asymptomatic subjects. J Clin Pathol. 1994;47:227-231. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 51] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Chen TS, Li FY, Chang FY, Lee SD. Immunoglobulin G antibody against Helicobacter pylori: clinical implications of levels found in serum. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2002;9:1044-1048. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 18. | Mauro M, Radovic V, Wolfe M, Kamath M, Bercik P, Armstrong D. 13C urea breath test for (Helicobacter pylori): evaluation of 10-minute breath collection. Can J Gastroenterol. 2006;20:775-778. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 19. | Gatta L, Ricci C, Tampieri A, Osborn J, Perna F, Bernabucci V, Vaira D. Accuracy of breath tests using low doses of 13C-urea to diagnose Helicobacter pylori infection: a randomised controlled trial. Gut. 2006;55:457-462. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 40] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 20. | Rasool S, Abid S, Jafri W. Validity and cost comparison of 14carbon urea breath test for diagnosis of H Pylori in dyspeptic patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:925-929. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 21. | Calvet X, Sánchez-Delgado J, Montserrat A, Lario S, Ramírez-Lázaro MJ, Quesada M, Casalots A, Suárez D, Campo R, Brullet E. Accuracy of diagnostic tests for Helicobacter pylori: a reappraisal. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:1385-1391. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 75] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Gisbert JP, Pajares JM. Review article: 13C-urea breath test in the diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection -- a critical review. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:1001-1017. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 237] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 242] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Zagari RM, Pozzato P, Martuzzi C, Fuccio L, Martinelli G, Roda E, Bazzoli F. 13C-urea breath test to assess Helicobacter pylori bacterial load. Helicobacter. 2005;10:615-619. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 26] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Perri F, Clemente R, Pastore M, Quitadamo M, Festa V, Bisceglia M, Li Bergoli M, Lauriola G, Leandro G, Ghoos Y. The 13C-urea breath test as a predictor of intragastric bacterial load and severity of Helicobacter pylori gastritis. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 1998;58:19-27. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 68] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Sheu BS, Lee SC, Yang HB, Lin XZ. Quantitative result of 13C urea breath test at 15 minutes may correlate with the bacterial density of H. pylori in the stomach. Hepatogastroenterology. 1999;46:2057-2062. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |