Published online Feb 7, 2010. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i5.596

Revised: November 4, 2009

Accepted: November 11, 2009

Published online: February 7, 2010

AIM: To investigate the usefulness of mild iron depletion and the factors predictive for histological improvement following phlebotomy in Caucasians with chronic hepatitis C (CHC).

METHODS: We investigated 28 CHC Caucasians with persistently elevated serum aminotransferase levels and non responders to, or unsuitable for, antiviral therapy who underwent mild iron depletion (ferritin ≤ 70 ng/mL) by long-term phlebotomy. Histological improvement, as defined by at least one point reduction in the staging score or, in case of unchanged stage, as at least two points reduction in the grading score (Knodell), was evaluated in two subsequent liver biopsies (before and at the end of phlebotomy, 48 ± 16 mo apart).

RESULTS: Phlebotomy showed an excellent safety profile. Histological improvement occurred in 12/28 phlebotomized patients. Only males responded to phlebotomy. At univariate logistic analysis alcohol intake (P = 0.034), high histological grading (P = 0.01) and high hepatic iron concentration (HIC) (P = 0.04) before treatment were associated with histological improvement. Multivariate logistic analysis showed that in males high HIC was the only predictor of histological improvement following phlebotomy (OR = 1.41, 95% CI: 1.03-1.94, P = 0.031). Accordingly, 12 out of 17 (70%) patients with HIC ≥ 20 μmol/g showed histological improvements at the second biopsy.

CONCLUSION: Male CHC Caucasian non-responders to antiviral therapy with low-grade iron overload can benefit from mild iron depletion by long-term phlebotomy.

- Citation: Sartori M, Andorno S, Rossini A, Boldorini R, Bozzola C, Carmagnola S, Piano MD, Albano E. Phlebotomy improves histology in chronic hepatitis C males with mild iron overload. World J Gastroenterol 2010; 16(5): 596-602

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v16/i5/596.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v16.i5.596

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection affects 130 million people worldwide causing chronic hepatic inflammation that in about 20% of the patients evolves to liver cirrhosis and/or hepatocellular carcinoma[1]. The progression of chronic hepatitis C (CHC) is not linear and is greatly influenced by a variety of factors including male gender, age at the infection, obesity, co-infection with hepatitis B or HIV viruses, alcohol consumption and iron overload[2,3]. The diffusion of anti-HCV therapies based on the association of pegylated interferon and ribavirin will probably modify the natural history of the disease, as more than half of the treated patients achieve a sustained eradication of the virus[4,5]. Nonetheless, for those patients who do not respond to anti-viral therapy, have contraindications to the use of interferon or cannot afford the therapy costs there is an urgent need of other therapeutic options capable of preventing the progression of the disease.

Mild hepatic iron accumulation is frequent in CHC patients and is associated with higher aminotransferase levels and more severe fibrosis[6]. Moreover, experimental studies have shown that dietary supplementation with iron worsens hepatic damage in HCV-infected chimpanzees and promotes the onset of hepatocarcinomas in transgenic mice expressing the HCV core protein[7,8].

Growing evidence indicates that HCV proteins stimulate the formation of reactive oxygen species within hepatocytes and oxidative stress associated with HCV infection is recognized as an important factor in the pathogenesis of hepatic damage in CHC[9]. In this context the capacity of iron to exacerbate oxidative damage suggests that iron accumulation might amplify oxidative stress-mediated events leading to both hepatocellular damage as well as to the pro-fibrogenic activation of hepatic stellate cells[10].

In recent years several groups have reported on the efficacy of iron reduction therapies based on phlebotomy in combination or not with an iron-restricted diet in reducing aminotransferase levels in CHC patients non-responders to the interferon treatment[11-16]. However, in many of these studies the iron depletion (serum ferritin below 20 ng/mL) was rather severe[13-16]. We have previously reported that menstruating women experienced a milder CHC than men of the same age in relation to the lower hepatic iron concentration (HIC) due to blood loss[17]. As patient compliance to long-term iron depletion is an important factor in the success of this therapy we have investigated whether, and in which conditions, mild iron depletion (serum ferritin ≤ 70 ng/mL) might be effective in inducing histological improvement in a group of Caucasian patients with CHC not responding to anti-viral therapy or having contraindications to the use of interferon, who were histologically re-evaluated within 2-5 years from the first liver biopsy and the start of iron depletion therapy.

In this study we investigated retrospectively 28 patients (21 men, 7 women; mean age 58 ± 7.6 years) with CHC, who were either non responders (n = 13) or had contraindications to antiviral therapy (n = 15) who gave informed consent to be treated between January 2001 and December 2006 exclusively with iron reduction by phlebotomy in two Italian centres (Ospedale Maggiore della Carità in Novara and Spedali Civili in Brescia) and underwent liver biopsies before phlebotomy and 2 to 5 years after the achievement of iron depletion. Criteria of exclusion were alcohol intake > 80 g/d, active drug addiction, HBs-Ag and/or HIV-Ab positivity, personal or familial history of haemochromatosis, haemoglobin < 13 g/dL for men and < 11 g/dL for women, interferon based therapy or immunosuppressive therapy during the last 6 mo, and refusal to undergo liver biopsies before and at the end of phlebotomy. The mean daily alcohol intake was evaluated by trained medical staff according to a standardized questionnaire, presented as part of a survey on life habits. Genetic tests for haemochromatosis mutations were not performed. However, HIC, iron index and the amount of iron removed during phlebotomy excluded phenotypic haemochromatosis.

All the patients underwent an initial period of bimonthly or monthly phlebotomy of 250 mL of blood, until serum ferritin levels of 35 ng/mL or less were reached. Thereafter, maintenance phlebotomies were performed every 1 to 3 mo during a minimum 2 years period to maintain a serum ferritin level at 70 ng/mL or less. In the case of haemoglobin values < 11 g/dL phlebotomy was postponed until haemoglobin levels exceeded the cut-off. For all patients histology was re-evaluated by a second liver biopsy after a period of 48 ± 16 mo, as part of a study approved by a local ethical committee to evaluate on an individual basis whether iron depletion by phlebotomy was effective and worth being continued.

None of the patients were treated with antiviral drugs during the study. Eight patients were on oral treatment for chronic unrelated diseases (hypertension, diabetes, vascular diseases) and another diabetic patient was treated with insulin. All were allowed to continue with these treatments throughout the study period.

The demographic, clinical and laboratory characteristics of the patients included in the present study are summarized in Table 1. The study was planned according to the guide-lines of the local ethical committee in conformity the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki.

| Variable1 | Range | SD | |

| Age (yr) | 58 | 43-73 | 7.6 |

| Gender (males/females) | 21/7 | ||

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 24.5 | 19-38.4 | 3.9 |

| HCV genotype (1/non-1) | 17/11 | ||

| Drug addiction (yes/no) | 2/26 | ||

| Previous transfusion (yes/no) | 11/17 | ||

| Alcohol abuse (yes/no)2 | 3/25 | ||

| Alcohol intake (g/d) | 15 | 0-60 | 18.35 |

| Treatment before recruitment (interferon based therapy/no treatment) | 13/15 | ||

| Aspartate aminotransferase (U/L, 0-40) | 108 | 46-275 | 58 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (U/L, 0-40) | 130 | 52-318 | 57 |

| γ glutamyl transpeptidase (U/L, 0-50) | 86 | 14-242 | 59 |

| Hemoglobin (g/100 mL, 13.7-17) | 14.7 | 11-18 | 1.6 |

| Serum iron (μmol/L, 11-32) | 24.3 | 73-240 | 6.9 |

| Transferrin saturation (%, 20-50) | 43 | 23-69 | 11 |

| Serum ferritin (ng/mL, 5-365) | 387 | 64-1051 | 238 |

| Hepatic iron grade (Searle’s score 0/1/2/3) | 6/17/15/0 | 0-2 | |

| Hepatic iron concentration (μmol/g dry tissue, < 25) | 23.3 | 7.5-40.5 | 7 |

| Histological grade (Knodell’s score, median) | 5 | 2-9 | |

| Histological stage (Knodell’s score 0/1/3/4) | 0/14/9/5 | 1-4 | |

| Advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis (Knodell’s stage score 3-4) (yes/no) | 14/14 | ||

| Steatosis grade (0/1/2/3)3 | 9/12/5/0 | 0-2 |

Liver biopsies were performed using a modified Menghini procedure. Five micron-thick sections were stained with haematoxylin/eosin, Masson’s trichrome and periodic acid-Schiff after diastase digestion as well as with the Gomori’s method for reticulin and the Perls’s method for iron staining. Only specimens with a minimum length of 15 mm and at least 6 portal tracts were considered adequate for histological assessment. Liver biopsy specimens were scored in a blind fashion (including the date - pre or post phlebotomy) by two expert pathologists (RB, CB) unaware of the clinical data. In the case of discordant opinions, the two examiners analyzed the discrepancies to reach a consensus.

The original histology activity index proposed by Knodell[18] was used for grading inflammation/necrosis and for staging fibrosis. By this scoring system inflammation/necrosis score ranges from 0 to 18 (0-10 periportal ± bridging necrosis, 0-4 intralobular degeneration and focal necrosis, 0-4 portal inflammation), while fibrosis stage includes only four stages: 0 (no fibrosis), 1 (fibrous portal expansion), 3 (bridging fibrosis), 4 (cirrhosis). Steatosis was scored semi-quantitatively as: 0, no steatosis, 1, steatosis ≤ 33% of hepatocytes, 2, steatosis in 34%-66% of hepatocytes, 3, > 66% of hepatocytes. Intrahepatic iron deposition was evaluated in specimens stained by the Perls’ method and evaluated using the Searle’s semi quantitative score[19]. As in previous studies, patients were defined to have a histological improvement when they showed at least one point reduction in the staging score or, in the case of an unchanged staging score, at least a two point reduction in the grading score[20,21].

HIC was measured by atomic absorption spectroscopy on a portion of each liver biopsy, as previously reported[22], and the values were expressed as μmol/g dry weight. Hepatic iron index was calculated to rule out phenotypic hemochromatosis.

Stata Statistical Software (release 9.0 College Station, Stata Corporation, TX, USA) was used in all the statistical analyses. Each variable predictive or associated with presence of histological response was analysed with univariate logistic regression. The variables selected by the univariate analysis were entered into logistic regression models with the use of a forward stepwise elimination algorithm (terms with P > 0.05 were eligible for removal). The paired Student’s t-test was used to compare the continuous variables among groups and the Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test was used to compare discrete variables among groups.

The long-term effects of mild iron depletion by phlebotomy were investigated in 28 CHC patients who were either non responders or had contraindications to antiviral therapy and received intensive phlebotomy followed by maintenance phlebotomy to maintain serum ferritin levels below 70 ng/mL. All the patients underwent a histological re-evaluation by a second biopsy within 2-5 years from the achievement of iron depletion. Two patients (a man aged 65 years and a woman aged 68 years who were treated with phlebotomy, respectively for 31 and 29 mo) were excluded from the study, because the second liver biopsy specimens did not meet the established criteria - minimum length and number of portal tracts - and, therefore, were not consider adequate. Both showed a decrease of HIC and aminotransferase levels > 50%.

The patients showed excellent compliance to phlebotomy. In particular, none of the patients reported increased fatigue, reduced exercise capacity, cheilosis, koilonychias or other side effects related to mild iron depletion.

The changes in clinical and laboratory values before and at the end of therapy are shown in Table 2. As expected hemoglobin, transferrin saturation, serum iron, serum ferritin, hepatic iron grade and the HIC were significantly decreased in phlebotomized patients (Table 2). At the time of the second biopsy aspartate aminotransferase (AST) (P < 0.0001), alanine aminotransferase (ALT) (P = 0.001) and γ glutamyltranspeptidase (GGT) (P = 0.004) levels were significantly lowered after phlebotomy (Table 2). Overall, ALT levels decreased in all 28 phlebotomized patients, while AST and GGT levels were lowered, in respectively, 27/28 (96%) and 22/28 (78%) of the patients (Table 3). Moreover, 7 out of the 28 phlebotomized patients (25%) achieved persistently normal aminotransferase levels during the iron-depleting treatment. No statistical correlation was found between the decreases of HIC and those of ALT levels (r = 0.22, P = 0.26). Mean alcohol intake slightly decreased during phlebotomy (15 ± 18 g/d vs 7.5 ± 9.7 g/d, P = 0.034) as a possible consequence of counseling. Serum HCV RNA levels were determined before and at the end of phlebotomy in 20/28 patients and no significant difference was observed (4.5 ± 3.6 × 106 copies/mL vs 4 ± 3.5 × 106 copies/mL, P = 0.11).

| Variable | First biopsy1 | Second biopsy1 | P2 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 24.5 ± 3.9 | 24.5 ± 3.8 | 0.93 |

| Alcohol intake (g/d) | 15 ± 18 | 7.5 ± 9.7 | 0.034 |

| HCV-RNA (× 106 copies/mL)3 | 4.54 ± 3.6 | 3.96 ± 3.5 | 0.11 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (U/L, 0-40) | 108 ± 58 | 64 ± 49 | 0.0001 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (U/L, 0-40) | 130 ± 57 | 70 ± 43 | < 0.0001 |

| γ glutamyl transpeptidase (U/L, 0-50) | 86 ± 59 | 56 ± 56 | 0.004 |

| Hemoglobin (g/100 mL, 13.7-17) | 14.7 ± 1.6 | 14 ± 1.4 | 0.0001 |

| Serum iron (μmol/L, 11-32) | 24.3 ± 6.9 | 16.4 ± 6 | < 0.0001 |

| Transferrin saturation (%, 20-50) | 43 ± 11 | 24.5 ± 10 | < 0.0001 |

| Serum ferritin (ng/mL, 5-365) | 387 ± 238 | 46 ± 51 | < 0.0001 |

| Hepatic iron grade (Searle’s score 0/1/2/3) | 6/17/5/0 | 27/1/0/0 | < 0.0001 |

| Hepatic iron concentration (μmol/g dry tissue, < 25) | 23.3 ± 7 | 8 ± 5.6 | < 0.0001 |

| Histological grade (Knodell’s score, median) | 5 | 4.5 | 0.43 |

| Histological stage (Knodell’s score 0/1/3/4) | 0/14/9/5 | 0/13/9/6 | 0.61 |

| Steatosis grade (0/1/2/3)4 | 9/12/5/0 | 11/11/3/1 | 0.41 |

| No. | Age (yr) | Gender | Alcohol | BMI | AST | ALT | HIC | Staging | Grading | HI | |||||||

| a | b | a | b | a | b | a | b | a | b | a | b | a | b | ||||

| 1 | 53 | M | 30 | 20 | 21.9 | 21.6 | 81 | 57 | 138 | 76 | 7.9 | 5.1 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 3 | Yes |

| 2 | 56 | M | 0 | 0 | 20.8 | 20.4 | 74 | 57 | 114 | 54 | 22.4 | 2.8 | 3 | 1 | 7 | 2 | Yes |

| 3 | 50 | M | 40 | 20 | 25.5 | 25.9 | 183 | 50 | 158 | 36 | 19.8 | 4.9 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 3 | Yes |

| 4 | 59 | M | 0 | 0 | 22.9 | 23.2 | 275 | 194 | 121 | 76 | 24.9 | 12.1 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 7 | No |

| 5 | 68 | M | 0 | 0 | 24.0 | 24.3 | 104 | 50 | 116 | 78 | 21.7 | 5.2 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 4 | No |

| 6 | 58 | F | 0 | 0 | 21.9 | 21.6 | 72 | 67 | 117 | 77 | 29.3 | 8.6 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 5 | No |

| 7 | 67 | F | 0 | 0 | 22.7 | 22.7 | 109 | 88 | 148 | 93 | 17.3 | 8.8 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 4 | No |

| 8 | 65 | F | 0 | 0 | 19.6 | 20.2 | 155 | 215 | 220 | 195 | 23.3 | 7.3 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 7 | No |

| 9 | 53 | M | 0 | 0 | 22.8 | 22.4 | 139 | 113 | 159 | 100 | 7.5 | 3.7 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 6 | No |

| 10 | 51 | M | 30 | 30 | 23.9 | 23.9 | 50 | 32 | 92 | 53 | 40.5 | 24.8 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 2 | Yes |

| 11 | 64 | F | 10 | 10 | 38.4 | 37.7 | 129 | 144 | 147 | 138 | 32.5 | 12.7 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 7 | No |

| 12 | 52 | M | 30 | 10 | 25.3 | 24.9 | 64 | 54 | 138 | 74 | 30.4 | 22.8 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 2 | Yes |

| 13 | 54 | M | 20 | 20 | 24.2 | 24.2 | 52 | 42 | 94 | 62 | 15.8 | 9.2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | No |

| 14 | 65 | M | 0 | 0 | 30.5 | 30.8 | 47 | 34 | 73 | 53 | 22.8 | 11.8 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 4 | No |

| 15 | 73 | M | 10 | 10 | 20.9 | 20.9 | 140 | 94 | 221 | 120 | 30.1 | 3.1 | 3 | 1 | 6 | 4 | Yes |

| 16 | 42 | M | 50 | 30 | 24.2 | 23.5 | 96 | 22 | 64 | 19 | 28.5 | 13.1 | 3 | 3 | 9 | 2 | Yes |

| 17 | 56 | M | 0 | 0 | 23.3 | 23.6 | 95 | 42 | 103 | 57 | 23.3 | 3.6 | 3 | 1 | 9 | 9 | Yes |

| 18 | 55 | M | 0 | 0 | 24.5 | 23.5 | 103 | 36 | 113 | 40 | 28.7 | 3.6 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 3 | Yes |

| 19 | 43 | M | 30 | 10 | 29.4 | 28.1 | 256 | 61 | 318 | 110 | 21.5 | 5.4 | 1 | 1 | 9 | 3 | Yes |

| 20 | 57 | M | 20 | 0 | 27.7 | 27.7 | 124 | 50 | 135 | 90 | 14.3 | 3.6 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 7 | No |

| 21 | 50 | F | 0 | 0 | 20.7 | 21.1 | 46 | 37 | 52 | 49 | 25.1 | 5.4 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 5 | No |

| 22 | 59 | M | 60 | 20 | 26.9 | 28.1 | 96 | 20 | 114 | 22 | 32.2 | 1.8 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 5 | Yes |

| 23 | 62 | M | 20 | 0 | 24.6 | 24.6 | 90 | 30 | 142 | 32 | 19.7 | 5.4 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 7 | No |

| 24 | 67 | M | 50 | 10 | 24.8 | 24.8 | 52 | 48 | 59 | 54 | 16.1 | 5.4 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 9 | No |

| 25 | 66 | M | 10 | 10 | 23.7 | 23.3 | 94 | 51 | 128 | 70 | 23.3 | 12.5 | 3 | 3 | 9 | 7 | Yes |

| 26 | 54 | F | 0 | 0 | 19.3 | 21.2 | 64 | 21 | 83 | 23 | 16.1 | 3.6 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 7 | No |

| 27 | 64 | F | 0 | 0 | 29.7 | 29.7 | 68 | 25 | 85 | 29 | 28.7 | 7.2 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 7 | No |

| 28 | 51 | M | 10 | 10 | 22.7 | 22.7 | 160 | 50 | 201 | 76 | 17.9 | 10.7 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 3 | No |

Overall, the scores for the necroinflammatory grading and the fibrosis staging were not modified by iron depletion (Table 2). However, by evaluating the histological improvement, as defined by at least one point reduction in the individual staging score or, in the case of unchanged staging, as at least two points reduction in the grading score, we observed that after phlebotomy 5 patients showed a reduction in both the grading and the staging scores and 7 had a two or more points reduction in the grading score with unchanged staging score (Table 3). Therefore, the frequency of histological improvements in the subjects undergoing mild iron depletion was 43% (12 out of 28).

Histological improvement was not significantly associated with the reduction of alcohol intake (reduction > 50%, P = 0.11), or body mass index (P = 0.12), nor was predicted by the magnitude of the reduction of the aminotransferase levels that occurred during iron depletion (reduction > 50%, P = 0.4) (Table 3). However, the patients with histological improvement had HIC significantly higher than in those without (26.55 ± 6.37 vs 20.81 ± 6.47, P = 0.028) (Table 3).

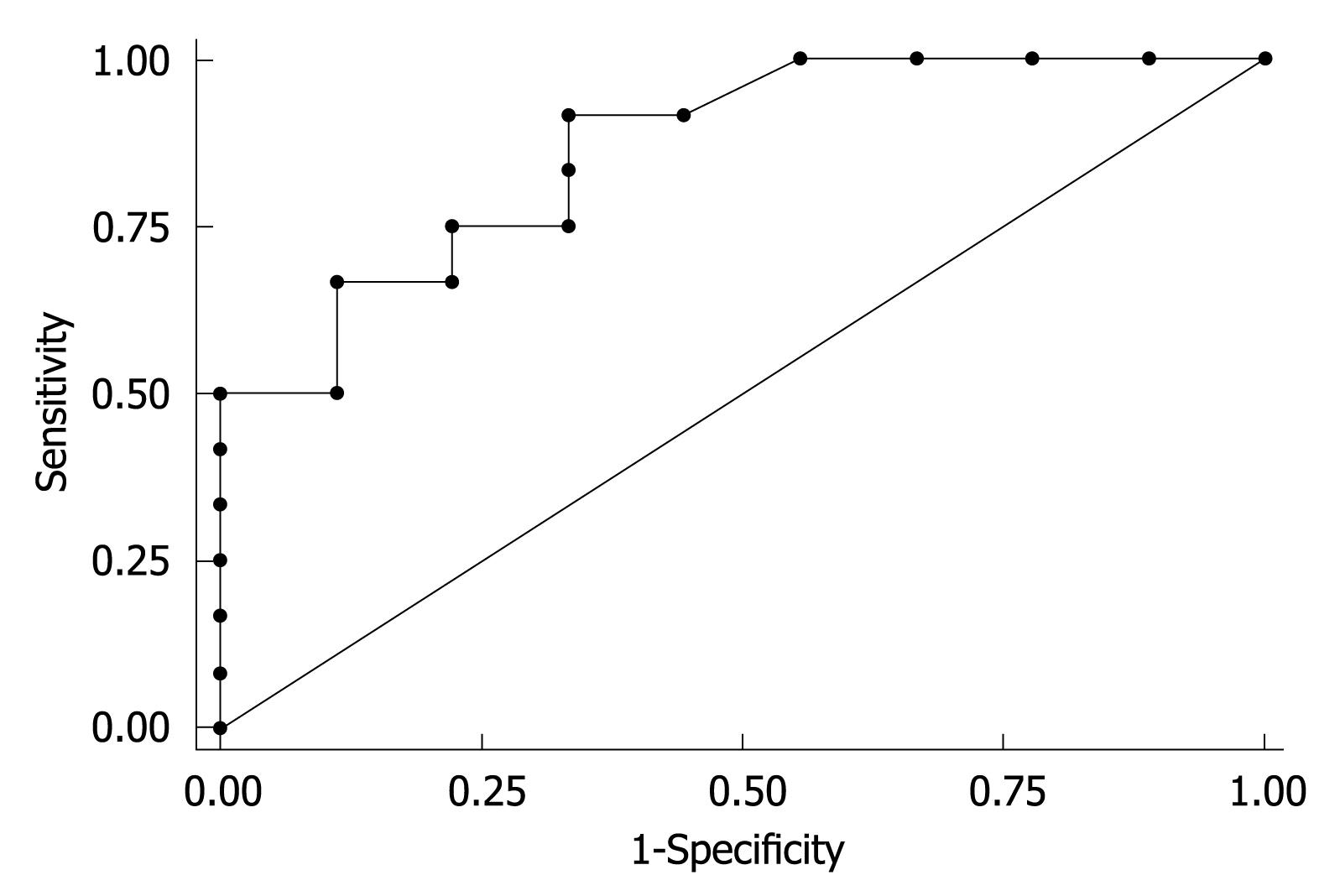

To determine the factors responsible for the histological improvement induced by long-term mild iron depletion, univariate logistic analysis of the putative predictors was performed (Table 4). We observed that only the males responded to treatment. Moreover, alcohol intake (P = 0.034), high histological grading (P = 0.013) and high HIC before phlebotomy (P = 0.043) were significantly associated with the histological improvement (Table 4). At multivariate logistic analysis, high HIC was the only independent predictor (OR = 1.41, 95% CI: 1.03-1.94, P = 0.031) of the histological improvement (Table 4). Furthermore, receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve showed that HIC ≥ 20 μmol/g was a suitable cut-off value (sensitivity 91.7%; specificity 66.7%) to discriminate CHC patients with histological improvement (Figure 1). Indeed, 12 out of 17 men (70%) with HIC ≥ 20 μmol/g dry tissue at the time of the first biopsy achieved histological improvement following the mild iron depletion.

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | P | |

| Univariate analysis | ||

| Age (yr) | 0.90 (0.80-1.01) | 0.085 |

| Male gender | Females are all non responders | |

| Drug addict (yes/non)1 | ||

| Previous transfusion (yes/non) | 1.19 (0.26-5.5) | 0.82 |

| Alcohol abuse (yes/non)2 | 3 (0.24 38) | 0.39 |

| Alcohol intake (g/d)3 | 1.06 (1.004-1.11) | 0.034 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 0.96 (0.78-1.17) | 0.69 |

| HCV Genotype (1 vs non-1) | 0.84 (0.18-3.95) | 0.82 |

| Previous antiviral treatment (yes/non) | 0.71 (0.16-2.23) | 0.66 |

| Days between the two liver biopsies | 1 (0.99-1.001) | 0.91 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (U/L) | 1.001 (0.99-1.01) | 0.79 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (U/L) | 1.006 (0.99-1.02) | 0.37 |

| γ glutamyl transpeptidase (U/L) | 1.002 (0.99-1.01) | 0.71 |

| Hemoglobin (g/100 mL) | 1.32 (0.79-2.21) | 0.28 |

| Serum iron (μmol/L) | 0.99 (0.98-1.02) | 0.9 |

| Transferrin saturation (%) | 0.97 (0.90-1.04) | 0.42 |

| Serum ferritin (ng/mL) | 1.004 (0.99-1.008) | 0.06 |

| Histological grade (Knodell’s score)3 | 2.4 (1.2-4.95) | 0.013 |

| Histological stage (Knodell’s score) | 1.32 (0.71-2.45) | 0.12 |

| Steatosis grade (0/1/2/3)4 | 0.7 (0.23-2.1) | 0.53 |

| Hepatic iron concentration (μmol/g dry tissue)3 | 1.16 (1-1.34) | 0.043 |

| Hepatic iron grading (Searle’s score) | 2.64 (0.69-10.1) | 0.15 |

| Multivariate analysis on male patients | ||

| Hepatic iron concentration (μmol/g dry tissue) | 1.41 (1.03-1.94) | 0.031 |

Iron accumulation is a common feature of liver biopsies from CHC patients and HCV infected patients with increased hepatic iron content show increased serum aminotransferase and liver fibrosis as compared to patients without iron accumulation[6]. Moreover, elevated iron indices have been associated with a poor response to interferon therapy[6].

At present, the mechanisms responsible for hepatic iron accumulation during HCV infection are not fully understood. It has been proposed that necroinflammation sustained by the virus together with genetic factors that modify iron trafficking might contribute to the alterations in iron homeostasis[6,23,24]. Recent studies in transgenic mice expressing the HCV polyprotein have shown that iron accumulation is associated with a low mRNA expression of hepcidin[25], a 25 amino acid peptide synthesized in the liver that regulates iron efflux from the enterocytes as well as the recycling of the metal by the macrophages[26]. Low liver hepcidin mRNA levels have also been detected in patients with CHC[27], suggesting the possibility that iron accumulation in CHC might be due to an inappropriate hepcidin response. According to the importance of iron as a worsening factor in the progression of CHC several studies have demonstrated that lowering of hepatic iron by phlebotomy alone or in combination with an iron-restricted diet reduces serum aminotransferase levels in CHC patients who failed a sustained virological response by interferon-based treatment[11-14]. Although phlebotomy does not interfere with HCV RNA levels[12], the efficacy of long term iron reduction in preventing the evolution of CHC has been substantiated by a recent histological follow-up study[16]. In their report Yano et al[16] showed that a 5 years iron-reducing treatment significantly lowered necroinflammatory grading and prevented the increase in fibrosis staging when they compared two sequential liver biopsies from non-responder CHC patients to interferon receiving or not phlebotomy. In addition, Kato et al[28] have reported that phlebotomy in combination with an iron-restricted diet significantly reduces the development of hepatocarcinomas associated with CHC. Although none of these studies reported side effects of iron lowering (serum ferritin below 20 ng/mL), the long term compliance to such a condition might be problematic in many patients. Therefore, in the present study, we investigated whether, and in which condition, mild iron depletion (serum ferritin below 70 ng/mL) might be effective in inducing histological improvement. Considering that iron depletion might be a simple and inexpensive treatment for those patients not responding to antiviral therapy or having contraindications to the use of interferon it would be important to verify whether similar results might be obtained by a milder iron depletion.

The present study shows that attaining serum ferritin levels ≤ 70 ng/mL is effective in decreasing aminotransferase release in Caucasian CHC patients and that 25% of the phlebotomized subjects achieve persistently normal aminotransferase levels during the iron-depleting treatment. Unlike Yano’s report[16] we did not observe significant changes in the median values of the necroinflammatory score among patients receiving phlebotomy. This likely reflects the lower degree of iron reduction achieved in our patients. However, the different scoring system used for evaluating necroinflammation, as well as the bias caused by the worsening of the grading in our phlebotomized patients who do not respond to iron depletion, might also account for the discrepancy. Nonetheless by taking into account the individual responses to treatment we have observed that mild iron depletion causes histological improvement in male subjects. In these patients multivariate logistic analysis reveals that increased HIC is the only independent predictor of the histological response to mild iron depletion. By using ROC curve we also found that a HIC ≥ 20 μmol/g can be used as cut-off to discriminate the CHC patients with high probability of histological improvement while undergoing mild long-term iron depletion.

So far the mechanisms responsible for the beneficial effects of phlebotomy in preventing the evolution of CHC have not been characterized in detail. Recent observations suggest that HCV proteins stimulate the formation of reactive oxygen species within the hepatocytes[9]. Thus, iron accumulation probably amplifies oxidative stress-mediated events, worsening both hepatocellular damage and fibrogenic processes. Indeed, mild iron accumulation in the liver of transgenic mice over-expressing HCV polyprotein enhances lipid peroxidation[8]. Supporting this view, a recent paper by Fujita et al[29] shows that the immunohistochemical detection of 8-hydroxy-2’deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG), a well recognized marker of oxidative stress, is strongly increased in liver biopsies from CHC patients. In these patients hepatic 8-OHdG levels are significantly associated with the hepatic iron content as well as with the necroinflammation indices. Interestingly, iron depletion by phlebotomy greatly reduces the liver content of 8-OHdG in patients with CHC[30], suggesting that the efficacy of phlebotomy in preventing the progression of CHC might rely on the reduction of oxidative damage promoted by the combination of HCV infection and iron accumulation. In this context, our observation that a high HIC is an independent predictor of the histological response to mild iron depletion further points to the possible importance of iron-mediated oxidative damage in the progression of CHC.

In conclusion, the study shows that mild iron depletion might be effective in improving liver histology in Caucasian CHC males with low-grade iron overload non-responders or with contraindications to established antiviral treatments. Prospective randomized studies should further address the long term efficacy of mild iron depletion in CHC patients with signs of iron accumulation.

Iron reduction therapies based on phlebotomy reduce aminotransferase levels and can improve liver histology in patients with chronic hepatitis C (CHC).

Although the management of patients with CHC has been improved by antiviral therapies, there is still an urgent need for alternative therapeutic options capable of preventing the progression of the disease in those patients who do not respond to antiviral drugs, have contraindications to the use of interferon and/or ribavirin or cannot afford the cost of therapy. Therefore, it is important to know which patients can benefit from iron reduction therapies.

The present study shows that male CHC Caucasian patients, with low-grade iron overload (hepatic iron concentration ≥ 20 μmol/g), non-responders or with contraindications to antiviral therapy can particularly benefit from mild iron depletion by long-term phlebotomy.

This retrospective study demonstrates that mild iron depletion is a safe and effective strategy for preventing the histological progression of the disease in males with CHC and low-grade iron overload. Further randomized prospective studies are warranted.

In this study mild iron depletion means the achievement of a ferritin level below 35 ng/mL after intensive phlebotomy and a ferritin level below 70 ng/mL during long-term maintenance phlebotomy.

This work is very interesting in demonstrating that serial phlebotomy still remains a current method of treatment despite its medieval origins. The results of this study are interesting to clinicians.

Peer reviewers: Chifumi Sato, Professor, Department of Analytical Health Science, Tokyo Medical and Dental University, Graduate School of Health Sciences, 1-5-45 Yushima, Bunkyoku, Tokyo 113-8519, Japan; Heitor Rosa, MD, PhD, Professor, Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Federal University School of Medicine, Rua 126 n.21, Goiania - GO 74093-080, Brazil

S- Editor Wang YR L- Editor O’Neill M E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | Lauer GM, Walker BD. Hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:41-52. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Feld JJ, Liang TJ. Hepatitis C -- identifying patients with progressive liver injury. Hepatology. 2006;43:S194-S206. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Massard J, Ratziu V, Thabut D, Moussalli J, Lebray P, Benhamou Y, Poynard T. Natural history and predictors of disease severity in chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 2006;44:S19-S24. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Di Bisceglie AM, Hoofnagle JH. Optimal therapy of hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2002;36:S121-S127. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Simin M, Brok J, Stimac D, Gluud C, Gluud LL. Cochrane systematic review: pegylated interferon plus ribavirin vs. interferon plus ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:1153-1162. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Alla V, Bonkovsky HL. Iron in nonhemochromatotic liver disorders. Semin Liver Dis. 2005;25:461-472. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Bassett SE, Di Bisceglie AM, Bacon BR, Sharp RM, Govindarajan S, Hubbard GB, Brasky KM, Lanford RE. Effects of iron loading on pathogenicity in hepatitis C virus-infected chimpanzees. Hepatology. 1999;29:1884-1892. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | Furutani T, Hino K, Okuda M, Gondo T, Nishina S, Kitase A, Korenaga M, Xiao SY, Weinman SA, Lemon SM. Hepatic iron overload induces hepatocellular carcinoma in transgenic mice expressing the hepatitis C virus polyprotein. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:2087-2098. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | Choi J, Ou JH. Mechanisms of liver injury. III. Oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of hepatitis C virus. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006;290:G847-G851. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Philippe MA, Ruddell RG, Ramm GA. Role of iron in hepatic fibrosis: one piece in the puzzle. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:4746-4754. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Hayashi H, Takikawa T, Nishimura N, Yano M, Isomura T, Sakamoto N. Improvement of serum aminotransferase levels after phlebotomy in patients with chronic active hepatitis C and excess hepatic iron. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89:986-988. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 12. | Di Bisceglie AM, Bonkovsky HL, Chopra S, Flamm S, Reddy RK, Grace N, Killenberg P, Hunt C, Tamburro C, Tavill AS. Iron reduction as an adjuvant to interferon therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis C who have previously not responded to interferon: a multicenter, prospective, randomized, controlled trial. Hepatology. 2000;32:135-138. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 13. | Yano M, Hayashi H, Yoshioka K, Kohgo Y, Saito H, Niitsu Y, Kato J, Iino S, Yotsuyanagi H, Kobayashi Y. A significant reduction in serum alanine aminotransferase levels after 3-month iron reduction therapy for chronic hepatitis C: a multicenter, prospective, randomized, controlled trial in Japan. J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:570-574. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 14. | Kawamura Y, Akuta N, Sezaki H, Hosaka T, Someya T, Kobayashi M, Suzuki F, Suzuki Y, Saitoh S, Arase Y. Determinants of serum ALT normalization after phlebotomy in patients with chronic hepatitis C infection. J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:901-906. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 15. | Sumida Y, Kanemasa K, Fukumoto K, Yoshida N, Sakai K. Effects of dietary iron reduction versus phlebotomy in patients with chronic hepatitis C: results from a randomized, controlled trial on 40 Japanese patients. Intern Med. 2007;46:637-642. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 16. | Yano M, Hayashi H, Wakusawa S, Sanae F, Takikawa T, Shiono Y, Arao M, Ukai K, Ito H, Watanabe K. Long term effects of phlebotomy on biochemical and histological parameters of chronic hepatitis C. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:133-137. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 17. | Sartori M, Andorno S, Rigamonti C, Grossini E, Nicosia G, Boldorini R. Chronic hepatitis C is mild in menstruating women. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;15:1411-1417. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 18. | Knodell RG, Ishak KG, Black WC, Chen TS, Craig R, Kaplowitz N, Kiernan TW, Wollman J. Formulation and application of a numerical scoring system for assessing histological activity in asymptomatic chronic active hepatitis. Hepatology. 1981;1:431-435. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 19. | Searle J, Kerr JFR, Halliday JW, Powell LW. Iron storage diseases. Pathology of the liver. 3rd ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingston 1994; 219-242. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 20. | Vilar Gomez E, Gra Oramas B, Soler E, Llanio Navarro R, Ruenes Domech C. Viusid, a nutritional supplement, in combination with interferon alpha-2b and ribavirin in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Liver Int. 2007;27:247-259. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 21. | Lissen E, Clumeck N, Sola R, Mendes-Correa M, Montaner J, Nelson M, DePamphilis J, Pessôa M, Buggisch P, Main J. Histological response to pegIFNalpha-2a (40KD) plus ribavirin in HIV-hepatitis C virus co-infection. AIDS. 2006;20:2175-2181. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 22. | Sartori M, Andorno S, La Terra G, Boldorini R, Leone F, Pittau S, Zecchina G, Aglietta M, Saglio G. Evaluation of iron status in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Ital J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;30:396-401. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 23. | Pietrangelo A. Hemochromatosis gene modifies course of hepatitis C viral infection. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:1509-1523. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 24. | Sartori M, Andorno S, Pagliarulo M, Rigamonti C, Bozzola C, Pergolini P, Rolla R, Suno A, Boldorini R, Bellomo G. Heterozygous beta-globin gene mutations as a risk factor for iron accumulation and liver fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C. Gut. 2007;56:693-698. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 25. | Nishina S, Hino K, Korenaga M, Vecchi C, Pietrangelo A, Mizukami Y, Furutani T, Sakai A, Okuda M, Hidaka I. Hepatitis C virus-induced reactive oxygen species raise hepatic iron level in mice by reducing hepcidin transcription. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:226-238. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 26. | Dunn LL, Rahmanto YS, Richardson DR. Iron uptake and metabolism in the new millennium. Trends Cell Biol. 2007;17:93-100. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 27. | Fujita N, Sugimoto R, Takeo M, Urawa N, Mifuji R, Tanaka H, Kobayashi Y, Iwasa M, Watanabe S, Adachi Y. Hepcidin expression in the liver: relatively low level in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Mol Med. 2007;13:97-104. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 28. | Kato J, Miyanishi K, Kobune M, Nakamura T, Takada K, Takimoto R, Kawano Y, Takahashi S, Takahashi M, Sato Y. Long-term phlebotomy with low-iron diet therapy lowers risk of development of hepatocellular carcinoma from chronic hepatitis C. J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:830-836. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 29. | Fujita N, Horiike S, Sugimoto R, Tanaka H, Iwasa M, Kobayashi Y, Hasegawa K, Ma N, Kawanishi S, Adachi Y. Hepatic oxidative DNA damage correlates with iron overload in chronic hepatitis C patients. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;42:353-362. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 30. | Kato J, Kobune M, Nakamura T, Kuroiwa G, Takada K, Takimoto R, Sato Y, Fujikawa K, Takahashi M, Takayama T. Normalization of elevated hepatic 8-hydroxy-2'-deoxyguanosine levels in chronic hepatitis C patients by phlebotomy and low iron diet. Cancer Res. 2001;61:8697-8702. [Cited in This Article: ] |