Published online May 28, 2010. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i20.2571

Revised: March 30, 2010

Accepted: April 6, 2010

Published online: May 28, 2010

Intrahepatic clear cell cholangiocarcinoma is very rare - only 8 cases have been reported. A 56-year-old Japanese man with chronic hepatitis B infection was diagnosed with a 2.2 cm hepatocellular carcinoma on imaging, and hepatic segmentectomy was performed. Histopathologically, the tumor cells had copious clear cytoplasm and formed glandular structures or solid nests. These pathological findings suggested the tumor was a clear cell variant of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Particular stains and radiological images suggested that the cause of the clear cell change had been glycogen, not mucin nor lipid. On immunohistochemical staining, cytokeratin (CK) 7 and CK19 were positive, whereas CK20 was negative. Vimentin was detected on the cell membranes, and CD56 was focally positive. The patient was given adjuvant chemotherapy and is currently free from the tumor 7 mo postoperatively. Careful follow-up with adequate postoperative supplementary chemotherapy is necessary because the characteristics of this type of tumor are unknown.

- Citation: Toriyama E, Nanashima A, Hayashi H, Abe K, Kinoshita N, Yuge S, Nagayasu T, Uetani M, Hayashi T. A case of intrahepatic clear cell cholangiocarcinoma. World J Gastroenterol 2010; 16(20): 2571-2576

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v16/i20/2571.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v16.i20.2571

Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC) represents about 15% of primary liver cancers[1]. Several studies in recent years have suggested that chronic hepatitis increases the carcinogenesis of ICC, with particular relevance of hepatitis B virus infection[2,3]. Therefore, it is often difficult to preoperatively distinguish ICC from hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), despite the high resolution of the latest imaging techniques[3].

In ICC, there is a quite rare variant, clear cell carcinoma[1,4-11]; until now, only 8 cases have been reported[4,7-11] (Table 1). The tumor is characterized by proliferation of the tumor cells with clear cytoplasm similar to renal clear cell carcinoma. The patients are in their 50 s or 60 s and no gender specificity has been found. The patients often have no underlying diseases. The background and risk factors of the ICC clear cell variant are unknown. Unlike typical ICC, there is no report on the relevance of hepatitis. The prognosis is relatively good. The mechanism for the clear cell change has been speculated to involve glycogen[4,7], mucin[7-9], or lipid[4,7], but it remains unclear.

| Yr | Age (yr)/sex | Location | Size (cm) | Hepatitis | Liver cirrhosis | Mechanism | Prognosis |

| 1998[10] | 64/F | Unknown | 12 | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown |

| 1998[11] | 62/M | Right lobe | 5 | - | - | Unknown | Dead, 14 mo; no treatment |

| 1998[7] | 72/M | Left lobe | 15 | Unknown | Unknown | Lipid >> glycogen | Alive, 30 mo |

| 1999[8] | 50/M | S6 | 1.5 | - | Unknown | Mucin | Alive, 12 mo |

| 2001[9] | 64/M | Right lobe | 6 | - | - | Unknown | Alive, 3 yr |

| 2007[4] | 51/M | S4a | 9 | Unknown | - | Lipid >> glycogen | Meta, 1 yr; dead, 3 yr |

| 2007[4] | 60/F | S5 | 4.5 | Unknown | - | Lipid >> glycogen | Alive, 1 yr |

| 2007[4] | 58/F | S5 | 2.3 | Unknown | - | Lipid >> glycogen | Alive |

| Present case | 56/M | S7 | 2.2 | HBV | - | Glycogen | Alive, 7 mo |

In this report, a case of intrahepatic clear cell cholangiocarcinoma with background chronic hepatitis B infection is presented. We discuss histopathological and radiological findings on the mechanism of clear cell change, and present a review of the literature.

A 56-year-old Japanese man who was found to have hepatic dysfunction on annual examination 3 years previously. He was diagnosed as having chronic hepatitis B (HBe-antigen (Ag)-positive and HBe-antibody (Ab)-negative). He was started on antiviral treatment with lamivudine {(-)-1-[(2R,5S)-2-hydroxymethyl-1,3-oxathiolan-5-yl]}. As the antiviral effect was not adequate, he was changed to a new drug, entecavir hydrate {9-[(1S,3R,4S)-4-hydroxy-3-(hydroxymethyl)-2-metylenecyclopentyl] guanine monohydrate cytosine}, to prevent tolerance emerging. As a result, HBV-DNA became negative, but the amplification signal of the virus remained detectable.

Follow-up abdominal ultrasonography 1 mo prior to surgery revealed a well-circumscribed, 2 cm mass with a halo at segment 7 (S7) of the liver. The tumor was diagnosed as HCC based on the findings of computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the abdomen. He was admitted to our hospital for surgery. At the time of admission, laboratory examination (Table 2) showed that α-fetoprotein (AFP) and protein induced by vitamin K antagonist or agonist (PIVKA)-II were in the normal range, and liver function tests were mildly abnormal (Child-Pugh Class A). Both HBs-Ag and HBs-Ab were high.

| Item | Data | Normal values |

| HBs-Ag (C.O.I) | 277.5 | < 1.0 |

| HBs-Ab (mIU/mL) | 165.1 | < 5.0 |

| Anti-HCV-Ab (C.O.I) | 0.1 | < 1.0 |

| α-fetoprotein (ng/mL) | 3.6 | ≤ 7.0 |

| PIVKA-II (mAU/mL) | 17.0 | < 40.0 |

| Carcinoembryonic antigen (ng/mL) | 2.4 | ≤ 5.0 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 181.0 | 128-25 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase ( IU/L) | 28.0 | 13-33 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (IU/L) | 21.0 | 8-42 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (IU/L) | 198.0 | 115-359 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (IU/L) | 207.0 | 119-229 |

| γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (IU/L) | 30.0 | 10-47 |

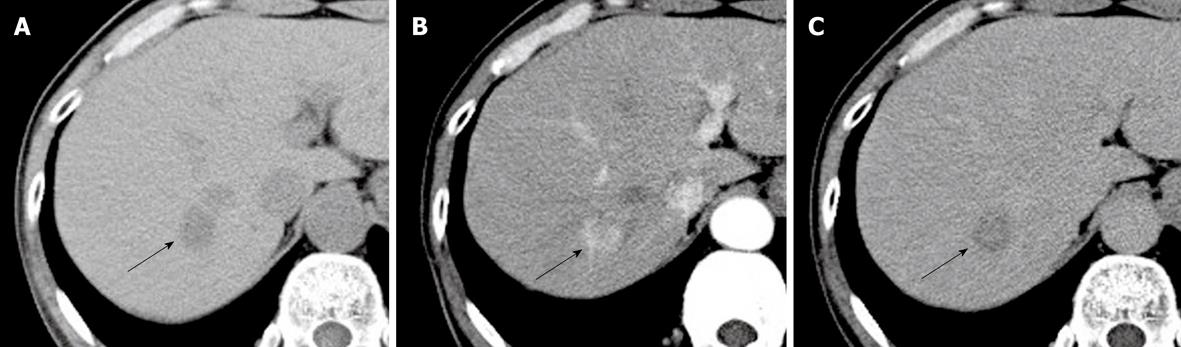

CT showed a well circumscribed mass in the posterosuperior S7 of the right lobe, measuring approximately 2 cm in diameter, with no calcification or fatty component (Figure 1A). After intravenous injection of iopamidol {N,N’-Bis [2-hydroxy-1-(hydroxymethyl)ethyl]-5-[(2S)-2-hydroxypropanoylamino]-2,4,6-triiodoisophthalamide} (total amount, 100 mL; injection rate, 3 mL/s), the lesion was well enhanced in the arterial phase (Figure 1B) and showed washout in the equilibrium phase (Figure 1C). Although the tumor margin was irregular without capsule-like enhancement, the internal enhancement pattern was consistent with classical HCC.

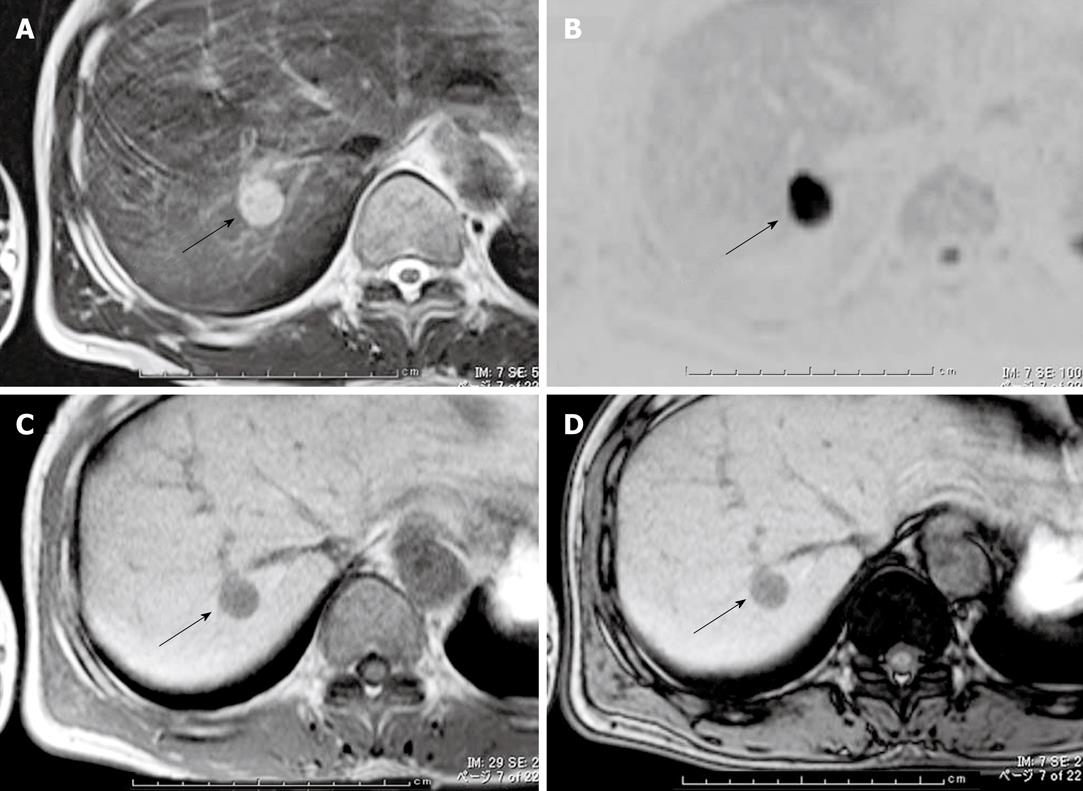

On MRI, the tumor was hypointense on T1-weighted imaging and hyperintense on T2-weighted imaging relative to the liver parenchyma (Figure 2A). Diffusion-weighted images showed that the lesions had very high intensity (Figure 2B). Opposed-phase images showed no signal intensity reduction compared with in-phase images (Figure 2C and D), indicating no fatty component in the tumor. The MRI were also consistent with HCC.

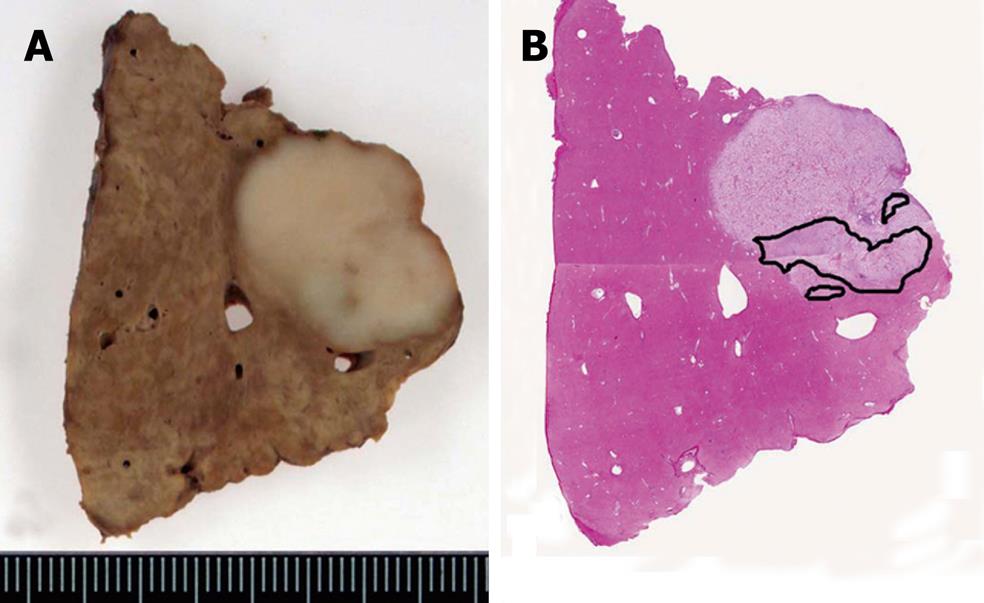

This tumor was diagnosed as an HCC from the imaging studies, and hepatectomy was performed. Based on the findings of intraoperative ultrasonography, the tumor was located close to the right hepatic vein, and subsegmental resection combined with the hepatic vein was performed. Macroscopically, the cut surface of the surgical specimen showed a yellowish-white, solid tumor, measuring 1.5 cm × 2.2 cm. Although the tumor margin was clear, there was no fibrous capsule. Neither hemorrhage nor large blood vessels were observed in the tumor. The outline margin with the surrounding liver was irregular, indicating cholangiocarcinoma (Figure 3).

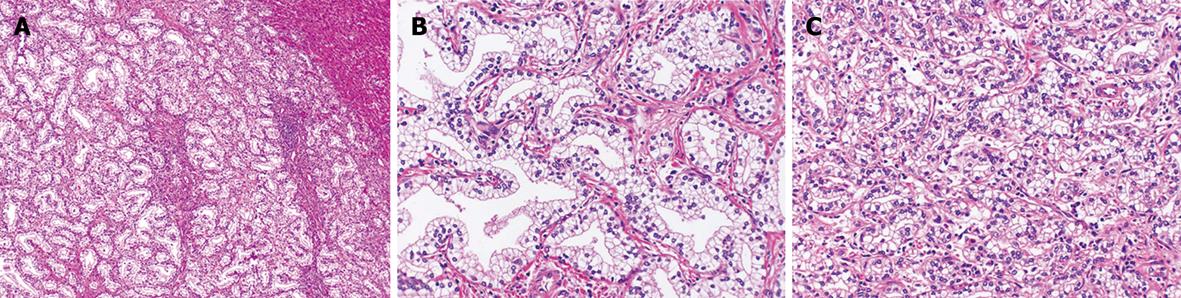

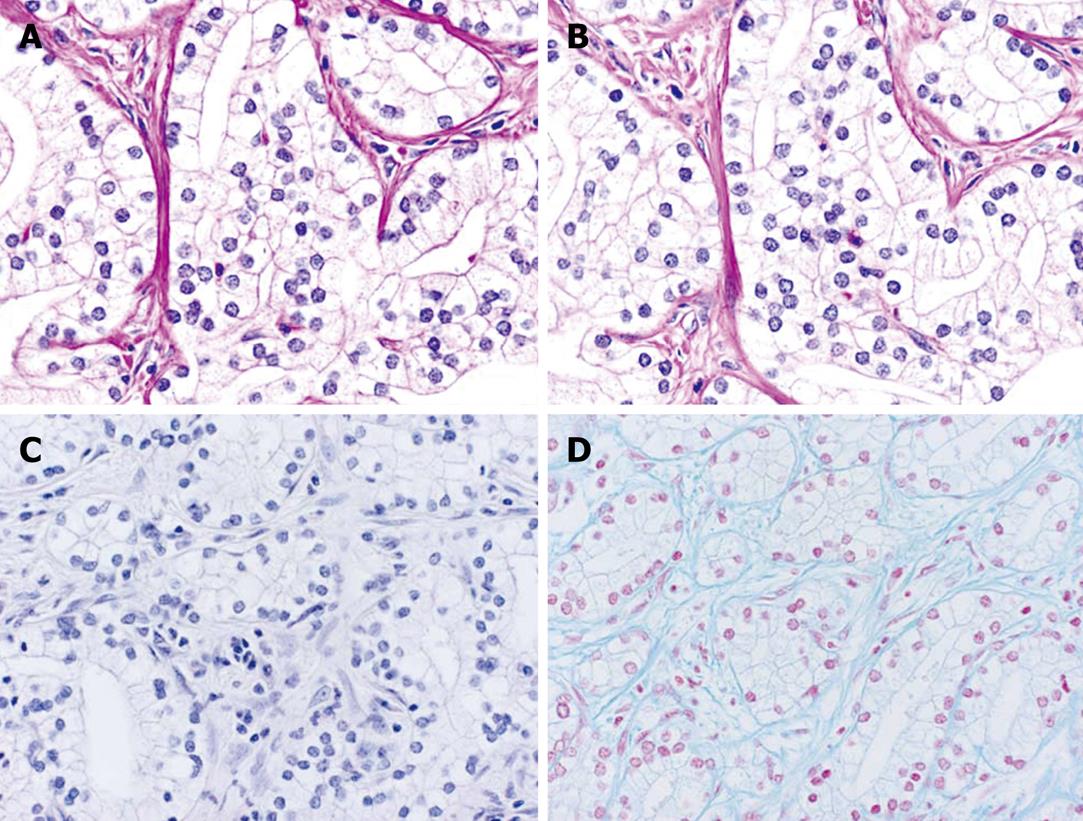

Pathologically, cuboidal to columnar cells with copious clear cytoplasm proliferated in the ductal structures (Figure 4A). Most of the tumor showed a well-differentiated glandular pattern (Figure 4B), and there was an area showing a poorly differentiated component without conspicuous lumens and forming solid nests (Figure 4C).

The tumor cells showed a weak reaction to periodic acid Schiff (PAS) and were digested by diastase treatment (Figure 5A and B). Neither mucicarmine nor Alcian blue stained the tumor cells (Figure 5C and D).

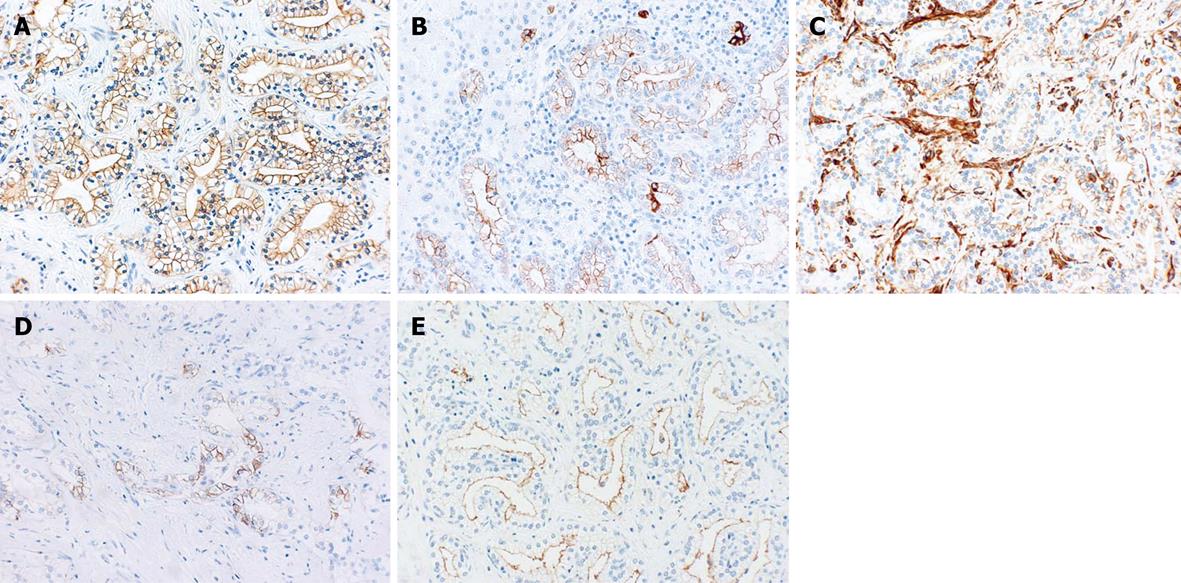

Immunohistochemical staining showed positive reactions for cytokeratin (CK) 7, CK19, vimentin (cell membranes), CD56 (focally), and epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) (membranes of the luminal side) (Figure 6), and negative reactions for CK20, AFP, hepatocyte, and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) (Table 3).

| Antibody | Company | Result |

| CK7 | DAKO | + |

| CK19 | DAKO | + |

| CK20 | DAKO | - |

| CAM5.2 | Becton, Dickinson, and Co. | + |

| EMA | DAKO | + |

| CA19-9 | DAKO | + focal |

| CEA | DAKO | - |

| CD56 | DAKO | + focal |

| AE1/3 | DAKO | + |

| Ki-67 (MIB-1) | Novocastra | 7.5%1 |

| p53 | Novocastra | + focal |

| Bcl-2 | DAKO | - |

| TTF-1 | DAKO | - |

| Hepatocyte | DAKO | - |

| a-Fetoprotein | DAKO | - |

| Vimentin | DAKO | - |

| CD10 | DAKO | - |

| S-100 protein | DAKO | - |

| Chromogranin | DAKO | - |

| Synaptophysin | DAKO | - |

Based on the histopathologic and immunohistochemical findings, the tumor was diagnosed as intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, clear cell variant. In the liver parenchyma, mild fatty change of hepatocytes, mild fibrosis and bridging of portal areas, and inflammatory infiltrates were observed.

Postoperatively, the patient was given adjuvant chemotherapy with tegafur-gimeracil-oteracil potassium {5-fluoro-1-[(2RS)-tetrahydrofuran-2-yl] uracil-5-chloro-2,4-dihydroxypyridine-monopotassium1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-2,4-dioxo-1,3,5-triazine-6-carboxylate} and is presently, 7 mo after surgery, free from tumor recurrence.

ICC is an epithelial malignancy that originates in the intrahepatic bile duct epithelium. Most ICCs are adenocarcinomas showing a tubular pattern, while some show cords or papillary structures[1]. Variants include adenosquamous carcinoma, sarcomatoid carcinoma, mucinous carcinoma, mucoepidermoid carcinoma, signet-ring cell carcinoma, and squamous carcinoma[1,4-6]. There is also a very rare variant, the clear cell variant[1,4-11].

Only 8 cases of the clear cell variant of ICC have been reported until now[4,7-11]. As the number of cases is very low, there is not a clear definition of histology and background disease. The reported background diseases were one case with diabetes mellitus and hypertension[8] and 2 cases with cholecystectomy[4] in the previous 8 reported cases. The present case had chronic hepatitis B as the background disease, that had not been reported.

The clear cell variant of ICC is characterized by tubular structures that consist of clear cells with copious clear cytoplasm, as well as a solid nest pattern[10] and papillary pattern[9]. The neoplastic cells are medium sized with a vacuolated or clear cytoplasm and have distinct cell borders[4,7]. The nuclei of the clear cells are round to ovoid and hyperchromatic[9]. In the present case, most of the tumor showed a well-differentiated glandular pattern, though there were some areas showing a poorly differentiated component without conspicuous lumens and forming solid nests. The cells were of medium size in the glandular areas and were smaller in the solid areas.

The cause of the clear cell change is said to be glycogen, based on electron microscopy and diastase digestion[4,7], mucin, based on positive staining with either mucicarmine or Alcian blue[4,7,9], and lipid, based on electron microscopy[4,7]. These cases may represent the same disease entity only because they show similar clear changes, despite having different causes. In the present case, mucin did not stain, the radiological findings did not support a fatty component[12], and only PAS with diastase suggested glycogen.

Immunohistochemically, tumor cells were CK7-positive[4,7-9,11] and CK20-negative[4,7-9], and both HepPar1[4,9] and AFP-negative[4,7,8,11]. CD56-positivity was reported recently by Haas et al[4], who argued that the reactivity was related to the clear cell change. However, ICCs with hepatitis B or C were also reported to be CD56-positive[13,14]. Therefore, it is uncertain whether the background is responsible for CD56 reactivity. As CD56 had not been determined in the reports before Haas et al[4], the reactivity for CD56 may be a new feature of clear cell ICC. The expression of vimentin usually relates to mesenchymal cells, though some epithelial tumors such as renal cell carcinoma (RCC), some ICCs[14], and some clear cell ICCs were seen in previous[4] cases and in the present case.

The clear cell variant of ICC should be distinguished from clear cell HCC and metastatic clear cell carcinomas arising from extrahepatic organs, especially RCC. Positivity for CK7 and negativity for CK20 correspond to cholangiocarcinoma[15]. Hepatocyte negativity, AFP-negativity, and formation of tubular structures can rule out HCC[4,7-9,11]. Lack of detection of mucin and small gland formation may be similar to cholangiolocellular carcinoma. Cholangiolocellular carcinomas can be differentiated in that they usually show numerous nodules composed of cells smaller than normal hepatocytes[16,17] and are negative for vimentin and CD56[14]. The differential diagnosis from RCC is achieved by detailed examination of the kidneys and negative staining for vimentin, CD10, and S-100 protein[4,7,9,10]. The present case was CD10- and S-100 protein-negative and vimentin-positive, but reactivity for vimentin in ICC has also been reported[4,14]. In addition, there were no abnormalities in the kidneys in careful radiological examination. Clear cell carcinoma of the gastrointestinal tract can be differentiated by detailed examination and histopathological findings.

Benign clear cell tumors of the bile ducts have seldom been reported except for 3 cases of atypical bile duct adenoma, clear cell type[9]. Immunohistochemically, they showed similar reactivity to their malignant counterpart, i.e. positivity for CK7, CEA, EMA and p53 and negativity for CK20. The only reported differential point was positivity rate of Ki-67 (MIB-1) of under 10% for bile duct adenomas and of over 50% for ICCs[9]. However, the ICC clear cell variant has also been reported to show positivity of less than 5%[4]. Thus, the conclusion has not been ascertained. Bile duct adenoma is said to be under 1 cm in diameter, located under the capsules and have less irregularity of the nuclei[1]. The present case showed Ki-67 positivity of under 10%. However, the size was 2.2 cm and it was located deep in the parenchyma apart from the capsule, with the nuclei showing irregularity, indicating a diagnosis of carcinoma.

ICC is said to have a poor prognosis[2,14] because of its tendency to be diagnosed at a late stage and the absence of effective treatment[3]. While the ICC clear cell variant has been reported to have a good prognosis[4,7-9], except for one death with metastasis after hepatic resection[4], and one case that had not been operated on because of underlying diseases and died 14 mo later[11]. In this case, the patient is currently free from disease, and the medication for chronic hepatitis B and the postoperative chemotherapy has been continued. Because the number of cases is very low, there is no evidence for the use of chemotherapy. Therefore, careful follow-up with sufficient postoperative supplementary chemotherapy is necessary to achieve longer survival.

Peer reviewer: Ki-Baik Hahm, MD, PhD, Professor, Gachon Graduate School of Medicine, Department of Gastroenterology, Lee Gil Ya Cancer and Diabetes Institute, Lab of Translational Medicine, 7-45 Songdo-dong, Yeonsu-gu, Incheon 406-840, South Korea

S- Editor Wang YR L- Editor Cant MR E- Editor Ma WH

| 1. | Nakanuma Y, Sripa B, Vatanasapt V, Leong AS-Y, Ponchon T, Ishak KG. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours, Pathology&Genetics: Tumours of the Digestive System. Lyon: IARC Press 2000; 173-180. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Zhou YM, Yin ZF, Yang JM, Li B, Shao WY, Xu F, Wang YL, Li DQ. Risk factors for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: a case-control study in China. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:632-635. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Kitajima K, Shiba H, Nojiri T, Uwagawa T, Ishida Y, Ichiba N, Yanaga K. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma mimicking hepatic inflammatory pseudotumor. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:398-402. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Haas S, Gütgemann I, Wolff M, Fischer HP. Intrahepatic clear cell cholangiocarcinoma: immunohistochemical aspects in a very rare type of cholangiocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:902-906. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Ishak KG, Goodman ZD, Stocker JT. Atlas of tumor pathology third series fascicle 31: tumors of the liver and intrahepatic bile ducts. Washington, DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology 1999; 245-263. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Nakajima T, Kondo Y, Miyazaki M, Okui K. A histopathologic study of 102 cases of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: histologic classification and modes of spreading. Hum Pathol. 1988;19:1228-1234. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Tihan T, Blumgart L, Klimstra DS. Clear cell papillary carcinoma of the liver: an unusual variant of peripheral cholangiocarcinoma. Hum Pathol. 1998;29:196-200. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | Falta EM, Rubin AD, Harris JA. Peripheral clear cell cholangiocarcinoma: a rare histologic variant. Am Surg. 1999;65:592-595. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | Albores-Saavedra J, Hoang MP, Murakata LA, Sinkre P, Yaziji H. Atypical bile duct adenoma, clear cell type: a previously undescribed tumor of the liver. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:956-960. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Logani S, Adsay V. Clear cell cholangiocarcinoma of the liver is a morphologically distinctive entity. Hum Pathol. 1998;29:1548-1549. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Adamek HE, Spiethoff A, Kaufmann V, Jakobs R, Riemann JF. Primary clear cell carcinoma of noncirrhotic liver: immunohistochemical discrimination of hepatocellular and cholangiocellular origin. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43:33-38. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 12. | Outwater EK, Blasbalg R, Siegelman ES, Vala M. Detection of lipid in abdominal tissues with opposed-phase gradient-echo images at 1.5 T: techniques and diagnostic importance. Radiographics. 1998;18:1465-1480. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 13. | Asayama Y, Aishima S, Taguchi K, Sugimachi K, Matsuura S, Masuda K, Tsuneyoshi M. Coexpression of neural cell adhesion molecules and bcl-2 in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma originated from viral hepatitis: relationship to atypical reactive bile ductule. Pathol Int. 2002;52:300-306. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 14. | Nakanuma Y, Sasaki M, Ikeda H, Sato Y, Zen Y, Kosaka K, Harada K. Pathology of peripheral intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma with reference to tumorigenesis. Hepatol Res. 2008;38:325-334. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 15. | Shimonishi T, Miyazaki K, Nakanuma Y. Cytokeratin profile relates to histological subtypes and intrahepatic location of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma and primary sites of metastatic adenocarcinoma of liver. Histopathology. 2000;37:55-63. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 16. | Steiner PE, Higginson J. Cholangiolocellular carcinoma of the liver. Cancer. 1959;12:753-759. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 17. | Komuta M, Spee B, Vander Borght S, De Vos R, Verslype C, Aerts R, Yano H, Suzuki T, Matsuda M, Fujii H. Clinicopathological study on cholangiolocellular carcinoma suggesting hepatic progenitor cell origin. Hepatology. 2008;47:1544-1556. [Cited in This Article: ] |