Published online Dec 28, 2009. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.6129

Revised: November 8, 2009

Accepted: November 15, 2009

Published online: December 28, 2009

We report a rare case of hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES) presenting with intractable gastric ulcers. A 71-year-old man was admitted with epigastric pain. Initial endoscopic findings revealed multiple, active gastric ulcers in the gastric antrum. He underwent Helicobacter pylori (H pylori) eradication therapy followed by proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy. However, follow-up endoscopy at 4, 6, 10 and 14 mo revealed persistent multiple gastric ulcers without significant improvement. The proportion of his eosinophil count increased to 43% (total count: 7903/mm3). Abdominal-pelvic and chest computed tomography scans showed multiple small nodules in the liver and both lungs. The endoscopic biopsy specimen taken from the gastric antrum revealed prominent eosinophilic infiltration, and the liver biopsy specimen also showed eosinophilic infiltration in the portal tract and sinusoid. A bone marrow biopsy disclosed eosinophilic hyperplasia as well as increased cellularity of 70%. The patient was finally diagnosed with HES involving the stomach, liver, lung, and bone marrow. When gastric ulcers do not improve despite H pylori eradication and prolonged PPI therapy, infiltrative gastric disorders such as HES should be considered.

- Citation: Park TY, Choi CH, Yang SY, Oh IS, Song ID, Lee HW, Kim HJ, Do JH, Chang SK, Cho AR, Cha YJ. A case of hypereosinophilic syndrome presenting with intractable gastric ulcers. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15(48): 6129-6133

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v15/i48/6129.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.15.6129

Hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES) is a rare disorder characterized by the overproduction of eosinophils in the bone marrow with persistent peripheral eosinophilia, tissue infiltration, and end-organ damage by eosinophil infiltration and the secretion of mediators[1]. The diagnosis of HES is based on marked eosinophilia exceeding 1500/mm3, a chronic course longer than 6 consecutive months, exclusion of parasitic infestations, allergic diseases and other etiologies for eosinophilia, and signs and symptoms of eosinophil-mediated tissue injury[1,2]. While HES can involve multiple organ systems, including bone marrow, heart, lung, liver, lymph node, muscle, and nerve tissue[1], gastrointestinal tract involvement is rare[1-3]. To date, only a handful of cases of HES presenting with gastritis or enteritis have been reported worldwide[4-9], and HES presenting with intractable gastric ulcers has not been reported. We report our case of a 71-year-old male patient with HES presenting with multiple intractable gastric ulcers with a review of the literature.

A 71-year-old man presented with epigastric pain. He underwent cholecystectomy 20 years previously due to acute cholecystitis with gallstones, and has intermittently taken nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) and corticosteroids on account of degenerative arthritis for 15 years. Other symptoms, as well as his past medical and family history, were otherwise unremarkable. The initial physical examination showed a flat, soft abdomen with normoactive bowel sounds with no sign of direct or rebound tenderness and no hepatosplenomegaly. Thoracic auscultation revealed no remarkable results. Routine complete blood count reported a leukocyte count of 7790/mm3 with 5.3% eosinophils, hemoglobin level of 12.1 g/dL, and a platelet count of 19 8000/μL. There were no noteworthy findings on simple chest and abdominal radiography. No specific cardiac abnormalities on standard 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) or Doppler echocardiogram were detected. ECG revealed normal sinus rhythm and the echocardiogram showed normal global left ventricular systolic function (estimated ejection fraction 70%).

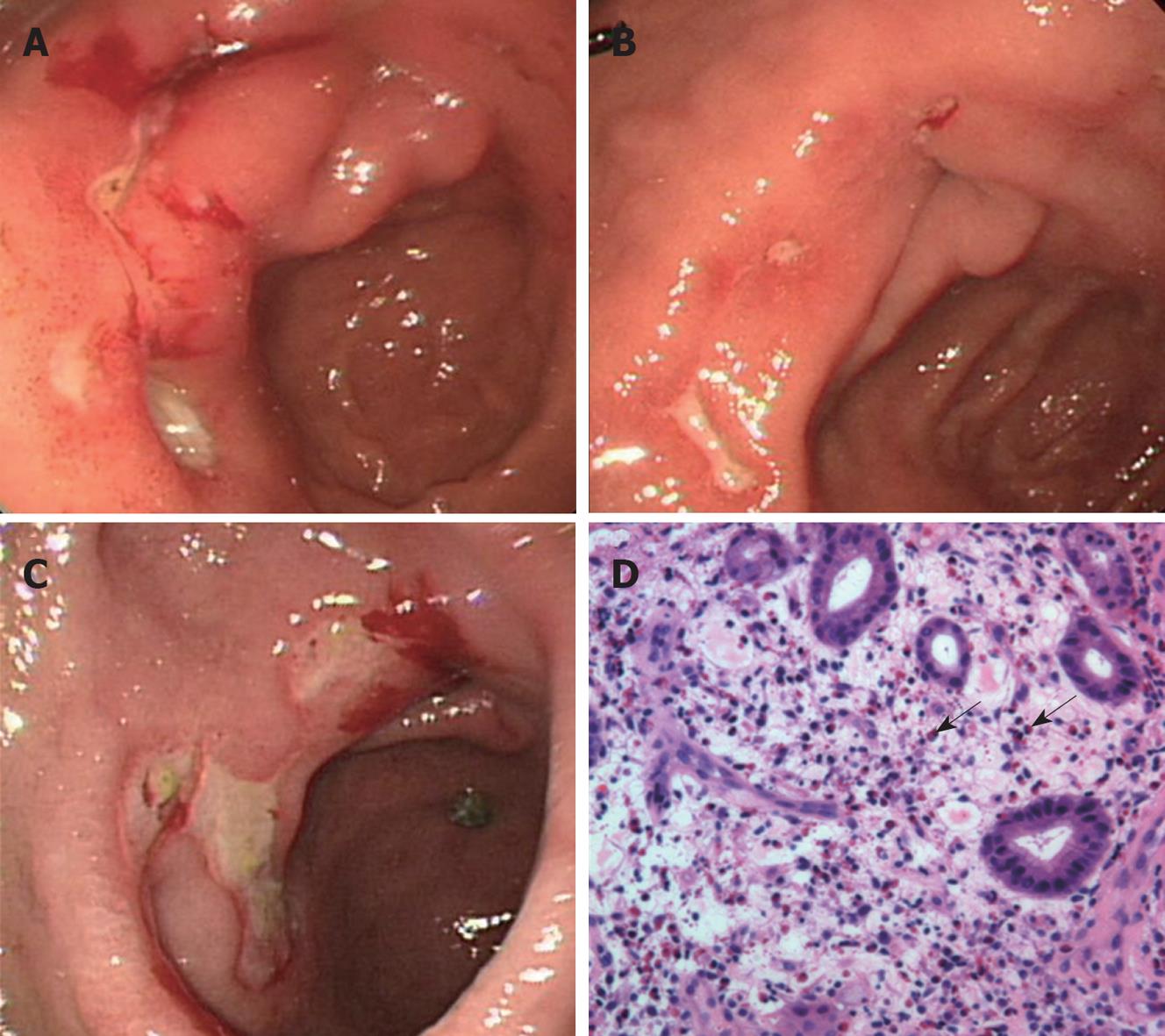

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) findings revealed several active gastric ulcers in the antrum of the stomach (Figure 1A). Biopsy findings showed an ulcer with Helicobacter pylori (H pylori). He underwent H pylori eradication therapy (lansoprazole 30 mg twice a day, clarithromycin 500 mg twice a day and amoxicillin 1000 mg twice a day for 7 d) followed by a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) and gastroprotective agent therapy for 2 mo. Follow-up EGD and biopsy performed after 2 mo showed that H pylori was eradicated, whereas multiple gastric ulcers were still noticeable with only slight improvement (Figure 1B). Follow-up endoscopy at 4, 6, and 10 mo showed persistent multiple gastric ulcers in the antrum despite continuous PPI treatment. Therefore, he was readmitted after 14 mo for etiological evaluation of the intractable gastric ulcers.

In the follow-up laboratory data, routine complete blood count showed a leukocyte count of 18 380/mm3 with 43% eosinophils, and an absolute eosinophil count of 7903/mm3. Serum chemistry showed: Aspartate aminotransferase/alanine aminotransferase (AST/ALT), 39/97 IU/L; total bilirubin/direct bilirubin, 0.3/0.1 mg/dL; alkaline phosphatase, 235 IU/L; total protein/albumin, 7.3/3.2 g/dL; and BUN/Cr, 14/1.1 mg/dL. Serum immunoglobulin E level was elevated to 2147 kU/L. In pulmonary function tests, pre-bronchodilator FEV1 was 2090 mL (95% of predicted value) and the bronchodilator response was negative. The allergen skin test was negative. There were no parasites or ova in stool specimens. ELISA of paragonimiasis westermani, Clonorchis sinensis, cysticercus, and sparganum were negative. Anti-HIV antibody and anti-nuclear antibody were negative.

In the EGD findings, multiple gastric ulcers were still found in the antrum of stomach (Figure 1C). The endoscopic biopsy specimen revealed prominent eosinophilic infiltrations of > 20 cells/HPF (Figure 1D). A retrospective review of the previous endoscopic biopsy specimens disclosed eosinophilic infiltration at the antrum which was overlooked at the initial evaluation.

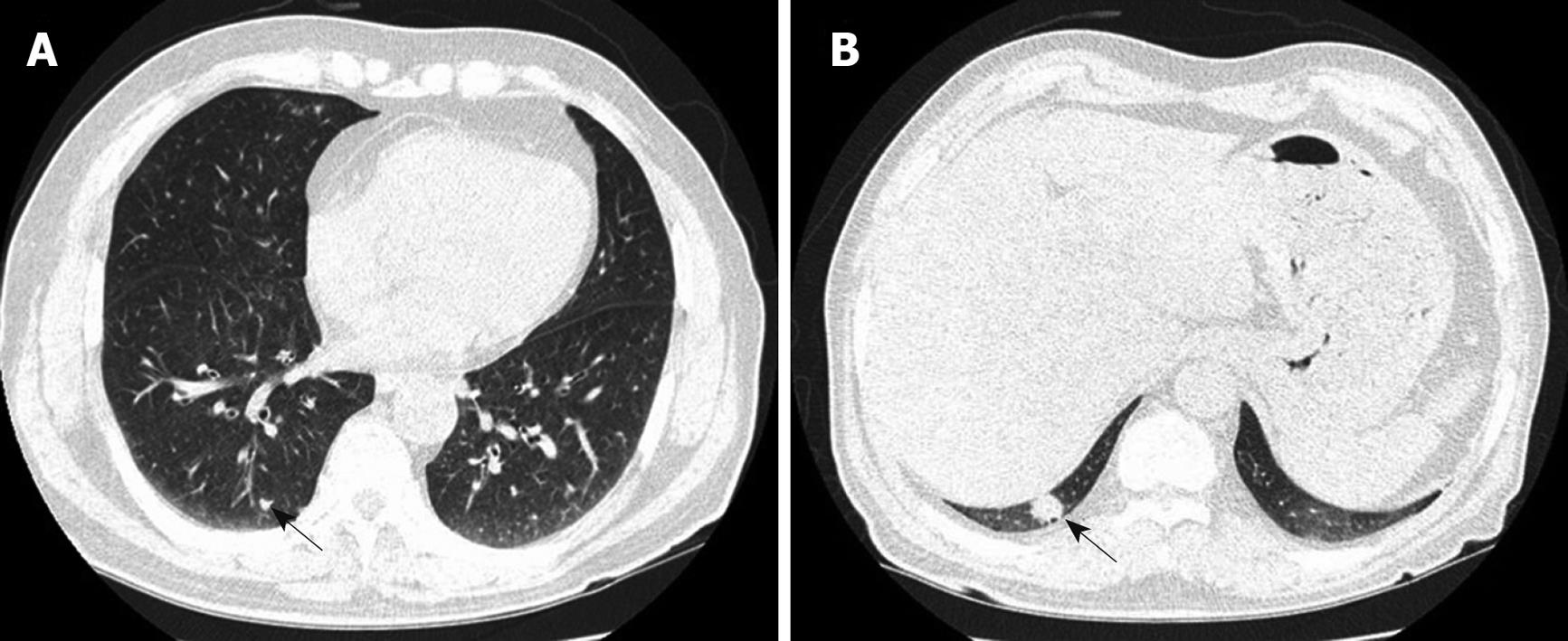

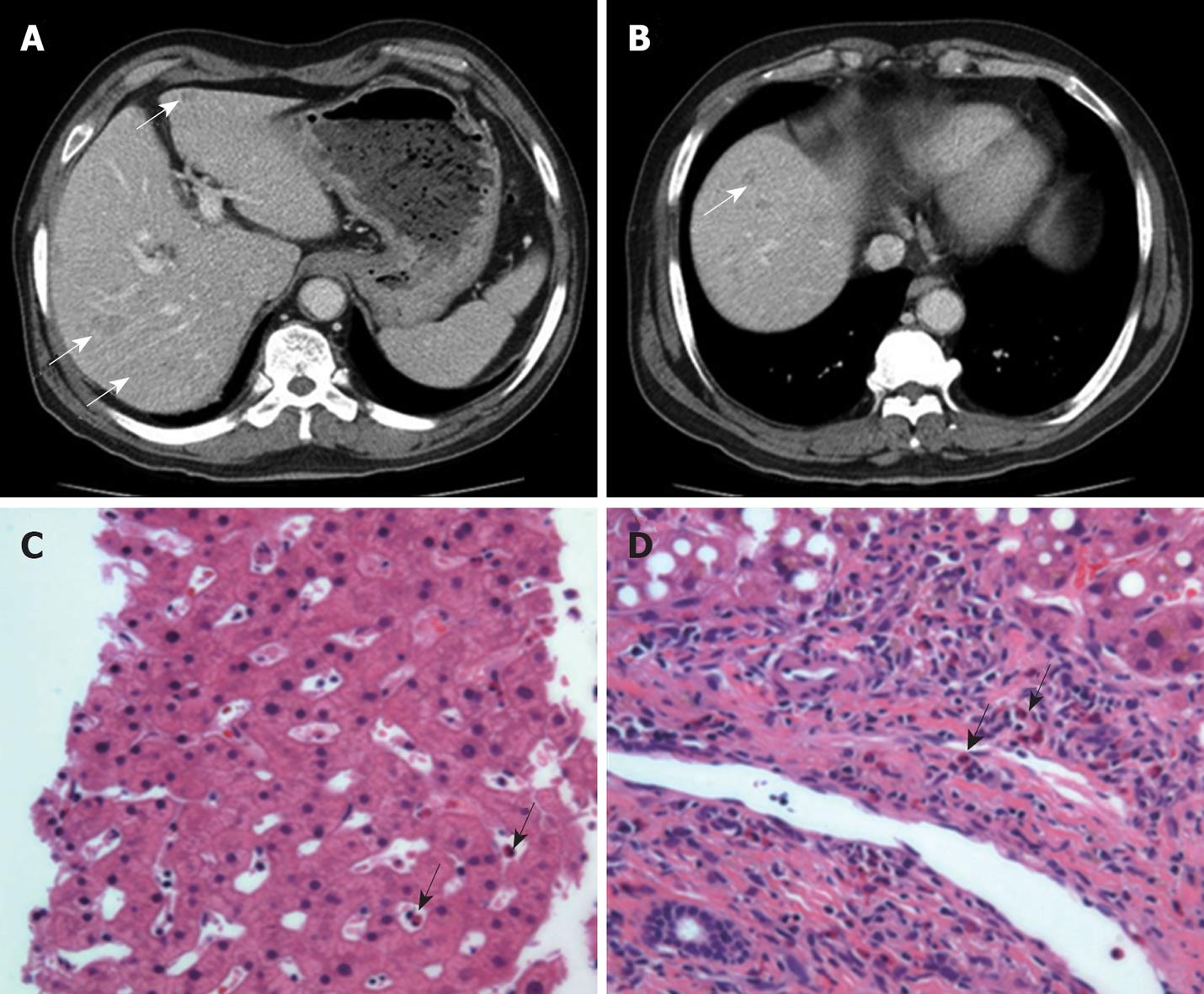

The chest computed tomography (CT) scan showed very tiny nodules in both lungs and approximately 15-mm-sized nodular lesions in the posterior basal segment of the right lower lobe (Figure 2A and B). In the abdominal-pelvic CT scan, multiple, small, and ill-defined low density lesions were found in both lobes of the liver (Figure 3A and B). The liver biopsy showed eosinophilic infiltration in the portal tract and sinusoid (Figure 3C and D).

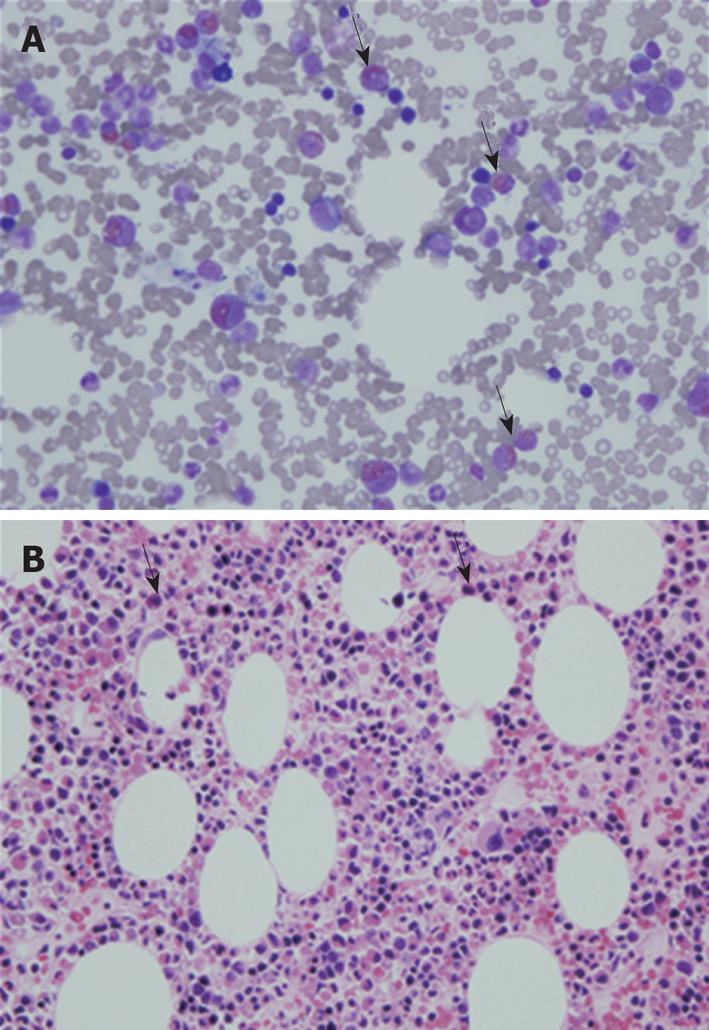

The peripheral blood smear report showed that there were no immature or dysplastic cells or morphologically abnormal eosinophils. The bone marrow aspiration smear showed an M:E ratio of 3.8:1 and an elevated eosinophil count of 22.2% (Figure 4A). Bone marrow biopsy findings also indicated eosinophilic hyperplasia, with increased cellularity of 70% and normal distribution of erythroid, myeloid, and megakaryocytic cell lineages (Figure 4B). The Fip1-like 1-platelet-derived growth factor receptor A fusion gene (FIP1L1-PDGFRA) rearrangement was not detected and there were no cytogenetic abnormalities.

This patient was finally diagnosed with HES involving the stomach, liver, lung, and bone marrow. He was treated with oral prednisolone 60 mg/d and PPI. After two weeks of therapy, clinical manifestations rapidly improved and peripheral blood eosinophilia had subsided.

HES is a rare disease characterized by unexplained persistent eosinophilia associated with multiple organ dysfunction[1,2]. In 1968, Hardy and Anderson[10] reported three patients with hypereosinophilia, hepatosplenomegaly, and cardiopulmonary symptoms, and first suggested that they had a nonmalignant disorder that belonged within the spectrum of disease termed hypereosinophilic syndrome. In HES, the degree of end-organ damage is heterogeneous, and there is often no correlation between the level or duration of eosinophilia and the severity of organ damage[1,3]. Also, the clinical manifestations are variable from one patient to another, depending on target-organ infiltration by eosinophils[11]. Virtually any tissue or organ can be affected, but cardiac involvement is the major cause of the morbidity and mortality associated with HES[1,9,12]. We did not find cardiac involvement in our patient.

Since Chusid et al[13] reported the analysis of fourteen cases of HES in 1975, some cases of HES involving the gastrointestinal (GI) tract have been reported. Ichikawa et al[4]reported a case of probable HES with a gastric lesion, López Navidad et al[5] reported a case of HES presenting as a form of epithelioid leiomyosarcoma of gastric origin, and Levesque et al[6] reported two cases of HES with predominant digestive manifestations. In Korea, Jung et al[8] reported a case of HES presenting as colitis and You et al[9] reported a case of HES presenting with various GI symptoms. However, HES presenting with intractable gastric ulcers has not been reported. Our patient suffered from HES presenting with multiple intractable gastric ulcers as well as liver, lung, and bone marrow involvement. The exact mechanism of eosinophil-related tissue damage, including gastric ulcer, is not known[3], but the accumulation of eosinophils can have direct cytotoxicity through the local release of toxic substances, including cationic proteins, enzymes, reactive oxygen species, pro-inflammatory cytokines, and arachidonic acid-derived factors[14].

The differential diagnosis of HES includes the disparate diseases associated with eosinophilia. Peripheral blood eosinophilia can be associated with allergic disorders, parasite infections, malignancies, and organ diseases, including eosinophilic gastroenteritis (EG) or eosinophilic pneumonitis due to eosinophilic infiltration[15]. In our patients, the bronchodilator response was negative and there was no symptom or sign of allergic disease. Even if allergic disease is present, the severe peripheral eosinophilia noted in our patient is unusual[15]. In addition, FIP1L1-PDGFRA gene rearrangement was not detected in bone marrow and there were no cytogenetic abnormalities. Therefore, we could rule out primary clonal eosinophilia such as eosinophilic leukemia.

HES may be confused with EG. The diagnosis of EG is based on the following three criteria: (1) the presence of gastrointestinal symptoms, (2) biopsies showing eosinophilic infiltration of one or more areas of the GI tract, or characteristic radiologic findings with peripheral eosinophilia, and (3) no evidence of parasitic or extraintestinal disease[16]. Because EG is also of unknown etiology, the distinction from HES must be made on clinical and pathologic bases[17,18]. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis characteristically does not extend beyond the target organ[1,18]. Hence, EG lacks the multiplicity of organ involvement often found in HES and does not have the predilection to develop secondary eosinophil-mediated cardiac damage[1,18]. Thus, EG can usually be distinguished from HES, although individual patients may on occasion present with overlapping features that confound classification[1,18]. In our patient, multiple organ involvement was demonstrated, and there was no other possible cause of severe eosinophilia.

In patients with eosinophilia who lack evidence of organ involvement, specific therapy is not needed[1]. Such patients can have prolonged courses without the need for therapeutic intervention[1]. However, patients with vital organ involvement require treatment[1]. The goals in the management of HES are as follows: (1) reduction of peripheral blood and tissue levels of eosinophils; (2) prevention of end-organ damage; and (3) prevention of thromboembolic events[1-3]. Corticosteroids have been used for decades in the treatment of HES and, with the exception of PDGFRA-associated HES, remain the first-line treatment for most patients[17]. Typically high-dose prednisone (1 mg/kg per day or 60 mg/d in adults) can be initiated[1,3]. A good response to corticosteroid therapy is associated with a better prognosis[1]. If patients are refractory or intolerant to corticosteroids, alternative therapies must be considered. Cytotoxic agents, including hydroxyurea, can be considered as second-line therapy[1,3]. Immunomodulatory agents including IFN-α, cyclosporine, and alemtuzumab can also be used[17]. In patients with FIP1L1-PDGFRA-positive HES, imatinib mesylate (Gleevec®), which selectively inhibits a series of protein tyrosine kinases, is considered first-line therapy[17].

In conclusion, we report a case of HES presenting with intractable gastric ulcers. The final diagnosis in this patient was HES involving the stomach, liver, lung, and bone marrow. Clinicians should bear in mind that gastric ulcers can develop in association with infiltrative disorders including HES. When gastric ulcers do not improve despite H pylori eradication and prolonged PPI therapy, an infiltrative gastric disorder, such as HES, should be considered.

Peer reviewer: Emad M El-Omar, Professor, MD (Hons), MB, ChB, FRCP (Edin), FRSE, BSc (Hons), Department of Medicine & Therapeutics, Institute of Medical Sciences, Aberdeen University, Foresterhill, Aberdeen, AB25 2ZD, United Kingdom

S- Editor Wang YR L- Editor Webster JR E- Editor Tian L

| 1. | Weller PF, Bubley GJ. The idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome. Blood. 1994;83:2759-2779. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Fauci AS, Harley JB, Roberts WC, Ferrans VJ, Gralnick HR, Bjornson BH. NIH conference. The idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome. Clinical, pathophysiologic, and therapeutic considerations. Ann Intern Med. 1982;97:78-92. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Wilkins HJ, Crane MM, Copeland K, Williams WV. Hypereosinophilic syndrome: an update. Am J Hematol. 2005;80:148-157. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Ichikawa K, Kasanuki JJ, Sueishi M, Imaizumi T, Koseki H, Kaneko R, Tomioka H, Tokumasa Y, Yoshida S. [A case of probable hypereosinophilic syndrome with a gastric lesion]. Nippon Naika Gakkai Zasshi. 1984;73:1697-1702. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | López Navidad A, Roca-Cusachs Coll A, Olazábal Zudaire A, Andreu Soriano J. Hypereosinophilic syndrome. [Hypereosinophilic syndrome. Presenting form of an epithelioid leiomyosarcoma of gastric origin]. Med Clin (Barc). 1986;86:565-566. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Levesque H, Elie-Legrand MC, Thorel JM, Touchais O, Gancel A, Hecketsweiller P, Courtois H. [Idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome with predominant digestive manifestations or eosinophilic gastroenteritis? Apropos of 2 cases]. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1990;14:586-588. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Hwang KE, Sung KC, Lee HM, Cho YK, Keum JS, Kim BI, Kim H, Chung ES, Lee SJ. A case with idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome involving the liver and GI tract. Korean J Gastroenterol. 1997;30:397-403. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | Jung HK, Jung SA, Lee HC, Yi SY. A case of eosinophilic colitis as a complication of the hypereosinophilic syndrome. Korean J Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;18:417-425. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | You IY, Kim MO, Chai JY, Hong ES, Chae HB, Park SM, Kim MK, Youn SJ, Jang LC, Sung RH. Two cases of eosinophilic gastroenteritis and one case of hypereosinophilic syndrome presenting with various gastrointestinal symptoms. Korean J Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;27:31-37. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Hardy WR, Anderson RE. The hypereosinophilic syndromes. Ann Intern Med. 1968;68:1220-1229. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Roufosse F, Cogan E, Goldman M. The hypereosinophilic syndrome revisited. Annu Rev Med. 2003;54:169-184. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 12. | Harley JB, Fauci AS, Gralnick HR. Noncardiovascular findings associated with heart disease in the idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome. Am J Cardiol. 1983;52:321-324. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 13. | Chusid MJ, Dale DC, West BC, Wolff SM. The hypereosinophilic syndrome: analysis of fourteen cases with review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1975;54:1-27. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 14. | Gleich GJ. Mechanisms of eosinophil-associated inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;105:651-663. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 15. | Kobayashi S, Inokuma S, Setoguchi K, Kono H, Abe K. Incidence of peripheral blood eosinophilia and the threshold eosinophile count for indicating hypereosinophilia-associated diseases. Allergy. 2002;57:950-956. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 16. | Talley NJ, Shorter RG, Phillips SF, Zinsmeister AR. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis: a clinicopathological study of patients with disease of the mucosa, muscle layer, and subserosal tissues. Gut. 1990;31:54-58. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 17. | Klion AD, Bochner BS, Gleich GJ, Nutman TB, Rothenberg ME, Simon HU, Wechsler ME, Weller PF, The Hypereosinophilic Syndromes Working Group. Approaches to the treatment of hypereosinophilic syndromes: a workshop summary report. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117:1292-1302. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 18. | Freeman HJ. Adult eosinophilic gastroenteritis and hypereosinophilic syndromes. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:6771-6773. [Cited in This Article: ] |