Published online Dec 14, 2009. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.5859

Revised: November 12, 2009

Accepted: November 19, 2009

Published online: December 14, 2009

Somatostatinomas are extremely rare neuroendocrine tumors of the gastrointestinal tract, first described in the pancreas in 1977 and in the duodenum in 1979. They may be functional and cause somatostatinoma or inhibitory syndrome, but more frequently are non-functioning pancreatic endocrine tumors that produce somatostatin alone. They are usually single, malignant, large lesions, frequently associated with metastases, and generally with poor prognosis. We present the unique case of a 57-year-old woman with two synchronous non-functioning somatostatinomas, one solid duodenal lesion and one cystic lesion within the head of the pancreas, that were successfully resected with a pylorus-preserving Whipple’s procedure. No secondaries were found in the liver, or in any of the removed regional lymph nodes. The patient had an uneventful recovery, and remains well and symptom-free at 18 mo postoperatively. This is an extremely rare case of a patient with two synchronous somatostatinomas of the duodenum and the pancreas. The condition is discussed with reference to the literature.

- Citation: Čolović RB, Matić SV, Micev MT, Grubor NM, Atkinson HD, Latinčić SM. Two synchronous somatostatinomas of the duodenum and pancreatic head in one patient. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15(46): 5859-5863

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v15/i46/5859.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.15.5859

Somatostatinomas are extremely rare and account for < 1% of functional APUD (amine precursor uptake and decarboxylation) cell neuroendocrine tumors of the gastrointestinal tract[1,2], with an annual incidence of 1 case per 40 million people[3]. Somatostatinomas usually occur within the pancreas but can also manifest in the duodenum, and less frequently in the jejunum and cystic duct[4-6]. Since the first description of somatostatinoma of the pancreas in 1977[7], and duodenum in 1979[8], 100-200 cases[1,2,9] have been described in the world literature, each occurring as a single lesion. A PubMed search resulted in a single case report of two somatostatinomas in the same patient, associated with type I neurofibromatosis[10].

We present an extremely rare case with two synchronous non-functioning somatostatinomas, one solid duodenal lesion and one cystic lesion within the head of the pancreas, without other disorders such as von Recklinghousen’s disease.

A 57-year-old woman presented with moderate epigastric pain in January 2007. Clinically, she was found to have only mild tenderness in the epigastrium, and all laboratory data were within normal limits. Ultrasound (US) and computed tomography (CT) revealed a 3 cm × 3 cm tumor in the duodenum, which was causing narrowing of its lumen to 1 cm, as well as a mass with a gas-filled cyst within the head of the pancreas (Figure 1). A cyst was also found within the head of the pancreas. A barium meal confirmed the duodenal luminal narrowing, and the tumor position above the ampulla of Vater, and upper gastrointestinal endoscopy provided a histological specimen that indicated a neuroendocrine tumor.

At laparotomy, two separate masses were found, one within the medial wall of the descending duodenum, and the second within the head of the pancreas. There were no visible or palpable secondaries within the liver or the peritoneal cavity. As both tumors appeared resectable, we proceeded with a pylorus-preserving Whipple’s procedure, as well as regional lymph node dissection. The postoperative recovery was uneventful and the patient remains well at 18 mo.

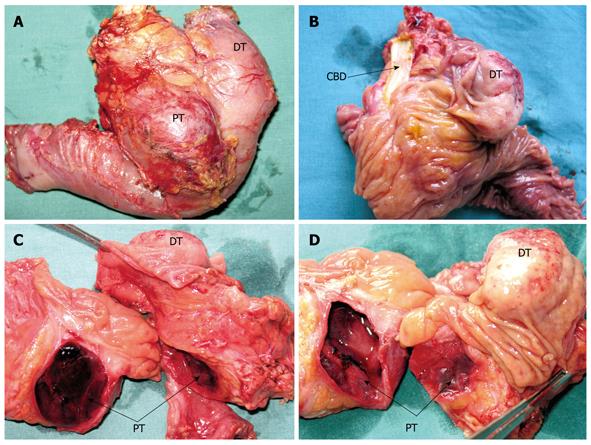

Macroscopically, the first lesion was a well-demarcated solid nodular suprapapillary tumor of the duodenum, 42 mm in its greatest diameter, 25 mm from the pylorus, and penetrating 15 mm through the duodenal wall to reach the superior margin of the head of the pancreas. There was no obvious intrapancreatic or choledochal infiltration of the tumor. A transverse section showed the tumor to be composed of soft grey/yellow granular and light brown nodular tissues (Figure 2A-D).

The second was a distinctive cystic and hemorrhagic lesion, with a tiny fistula with the duodenum, within the enlarged head of the pancreas. The lesion measured 36 mm in its greatest diameter, contained necrotic and hemorrhagic coagula, and was surrounded by a thin fibrotic pseudocapsule zone. The inner surface of the cyst contained a layer of spongy tan/light brown tissue. There were no other notable micromorphological findings in the remainder of the resected pancreatic specimen.

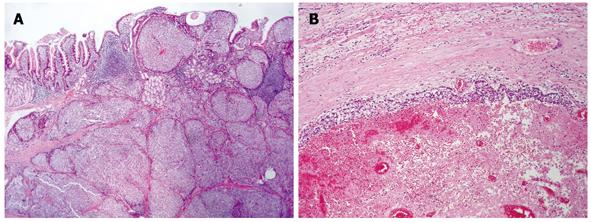

Histopathology of the duodenal tumor revealed a dominant micronodular and insular growth of epithelioid cells, with rare trabecular or solid microorganization, and without necrotic areas (Figure 3A). The tumor cells were packed tightly with a high degree of uniformity and ill-defined ovoid/polygonal shapes. Their round nuclei were situated centrally, with low nuclear anaplasia and two mitotic figures per 10 high-power fields. However, despite expansive growth and a clearly demarcated border, peritumoral venous infiltration and microinfiltration of the periduodenal fatty tissue was found frequently.

The pseudocystic lesion of the pancreas showed an obvious neoplastic proliferation with similar histology seen within the thin neoplastic peripheral rim. This narrow peripheral zone was surrounded by a pseudocapsule, and the vast majority of cells contained within the cyst showed hemorrhagic and necrotic changes (Figure 3B). No extrapancreatic spread or involvement of the regional lymph nodes was found, although focal venous infiltration was observed.

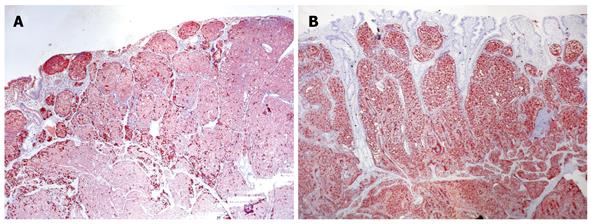

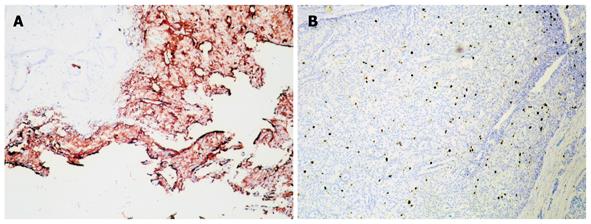

Immunohistochemistry confirmed that both tumors were derived from a similar cell origin. There was a significant cytoplasmic immunoexpression of pan-neuroendocrine markers: chromogranin A occurred more intensely and frequently than synaptophysin (Figure 4A). There was strong somatostatin immunoreactivity in over half of the duodenal tumor cells (Figure 4B) and 70% of the pancreatic tumor cells (Figure 5A), where a small percentage of cells that coexpressed glucagon and pancreatic polypeptide immunoreactivity were also found. Proliferative activity measured using Ki-67 protein labeling indices was approximately 3.5% in both tumors (Figure 5B). The final histopathological diagnosis of somatostatinoma of the duodenum and the pancreas was made in tumor stages pTNP: 2T (T3+T2) N0 Mx LOVI. It was concluded that despite the absence of regional and distant metastases, neither tumor could be categorized as benign, given their histopathological features, size, mitotic counts and proliferative activities.

One and a half years after surgery, the patient is symptom-free, with normal US and scintigraphy of the liver.

Somatostatinomas are extremely rare gastrointestinal tumors with an annual incidence of 1 case per 40 million adults[3]. Two-thirds of somatostatinomas occur within the pancreas, with the duodenum being the next most common site[9]; although some authors have found equal frequencies[11]. They can occur at any age (range: 21-91 years)[1,9], and pancreatic somatostatinomas show a slight female predominance (67%), with extrapancreatic sites being more often present in men[1]. Forty-five percent of cases exist as part of multiple endocrine neoplasia type I syndrome or von Hippel-Lindau disease[1] and it is vital to confirm or refute these associated conditions. Duodenal somatostatinomas may be associated with von Recklinghausen’s neurofibromatosis[1,12,13].

Differences exist between the pancreatic and extrapancreatic types. Duodenal somatostatinomas usually are located in the second part of the duodenum, and most frequently in the ampullary or periampullary regions. Approximately 30% have lymph node оr liver secondaries at the time of diagnosis, although these are less frequent when tumors are < 2 cm[9]. About two-thirds of these tumors contain psammoma bodies within the lumina of their glandular structures, and their biological behavior is similar to that of carcinoid tumors. As a result of their location, patients often present earlier with bile duct obstruction and jaundice, hence the reason for their earlier discovery, earlier surgery, smaller sizes and lower rates of metastasis[1,2,9].

Almost 60% of pancreatic somatostatinomas are located in the head of the pancreas, and about 30% in the tail[1]. They usually are larger (mean size: 5-6 cm), and are considered more malignant with a 70% incidence of metastases[9]. Often the mass effect of the tumor itself leads to its diagnosis[11].

Although somatostatin is the main secretory product, at least 10% of somatostatinomas produce other hormones, including glucagon, gastrin, vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP), insulin, calcitonin, and adrenocorticotrophic hormones[14-16], and the clinical picture may be dominated by the effects of these secreted hormones[4]. Duodenal somatostatinomas more frequently secrete gastrin, VIP and calcitonin[9], while pancreatic somatostatinomas are also more likely to be multihormonal[11].

Regardless of their plasma somatostatin levels, most patients present with indolent, nonspecific symptoms including vague abdominal pain, weight loss and a change in bowel habits[1,2]. The classical somatostatinoma or inhibitory syndrome, which includes cholelithiasis, mild diabetes mellitus and steatorrhea with diarrhea, is present in only a small number of patients[1,4]. The syndrome is the result of the inhibitory effects of somatostatin on endocrine and exocrine secretion, as well as its suppression of stomach and gallbladder motility[9]. It occurs far less with duodenal than other extrapancreatic somatostatinomas[1], and this may be due to their earlier diagnosis, release of inactive peptides, or lower secretory activity of the smaller duodenal tumors[2].

The preoperative diagnosis of somatostatinoma is extremely difficult to establish unless there is a high clinical suspicion based on the patient’s symptomatology[1], although elevated fasting serum levels of somatostatin that cause the somatostatinoma syndrome can be diagnostic, particularly if associated with tumors larger than 4 cm[1]. CT and magnetic resonance imaging often fail to identify small tumors of the duodenum[13], and these are often discovered during upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. The diagnosis is then made based upon histological assessment of biopsy specimens during upper gastrointestinal endoscopy[1,13] or endoscopic US[17]; with the exact histopathological diagnosis ultimately based on the resected specimen[1,2]. Once the preoperative diagnosis is established, somatostatin receptor scintigraphy and positron emission tomography can localize accurately the disease[18], and are particularly useful in identifying occult metastatic spread and recurrent disease[19]. Scintigraphy positive for metastatic spread can obviate unnecessary surgery[2]; similarly a negative scan can indicate that curative resection is a possibility[19].

Surgical resection is the only form of curative treatment[1] smaller lesions (< 2 cm) by enucleation larger lesions with extensive Whipple’s type resections[20] (due to their common localization in the head of the pancreas and duodenum), or other similar anastomoses. Unfortunately, in only 60%-70% of surgical cases is the tumor completely resected[1,3]. Debulking surgery should also be considered in the presence of metastatic secondaries because this may lead to improved survival and quality of life, especially in those with somatostatinoma syndrome[1,21]. Indeed, palliation for bile duct obstruction, pain or hormonal excess is beneficial in most unresectable cases[1].

For patients with liver secondaries that are not amenable to resection or ablation, hepatic artery embolization or chemoembolization may be an effective therapy for symptomatic palliation[22]. Adjuvant chemotherapy is not advocated after complete resection[1], however, in locally unresectable cases or in metastatic somatostatinoma, chemotherapeutic agents have been used with moderate clinical responses[1,23].

Somatostatinomas are slow-growing lesions and long-term survival is possible[11], even with no intervention. Unfavorable prognostic predictors include tumor size > 3 cm, poor cytological differentiation, regional and/or portal vein metastases, a non-functioning tumor, and incomplete surgical resection[1].

Ultimately, patients with localized disease and a successful resection are the most likely to achieve a cure[2], however, even in the presence of metastases, the 5-year survival for patients undergoing surgical resection with adjuvant chemotherapy approaches 40%[1].

Peer reviewer: Wei Tang, MD, EngD, Assistant Professor, H-B-P Surgery Division, Artificial Organ and Transplantation Division, Department of surgery, Graduate School of Medicine, The University of Tokyo, Tokyo 113-8655, Japan

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Kerr C E- Editor Ma WH

| 1. | House MG, Yeo CJ, Schulick RD. Periampullary pancreatic somatostatinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2002;9:869-874. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Marakis G, Ballas K, Rafailidis S, Alatsakis M, Patsiaoura K, Sakadamis A. Somatostatin-producing pancreatic endocrine carcinoma presented as relapsing cholangitis -- a case report. Pancreatology. 2005;5:295-299. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Choi YS, Park JK, Lee SH, Yoon WJ, Lee JK, Ryu JK, Kim YT, Yoon YB. [A case of pancreatic somatostatinoma]. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2006;48:351-354. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Ozbakir O, Kelestimur F, Ozturk F, Sozuer E, Unal A, Patiroglu TE, Guven K. Carcinoid syndrome due to a malignant somatostatinoma. Postgrad Med J. 1995;71:695-698. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Semelka RC, Custodio CM, Cem Balci N, Woosley JT. Neuroendocrine tumors of the pancreas: spectrum of appearances on MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2000;11:141-148. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Roberts L Jr, Dunnick NR, Foster WL Jr, Halvorsen RA, Gibbons RG, Meyers WC, Feldman JM, Thompson WM. Somatostatinoma of the endocrine pancreas: CT findings. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1984;8:1015-1018. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Larsson LI, Hirsch MA, Holst JJ, Ingemansson S, Kuhl C, Jensen SL, Lundqvist G, Rehfeld JF, Schwartz TW. Pancreatic somatostatinoma. Clinical features and physiological implications. Lancet. 1977;1:666-668. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | Kaneko H, Yanaihara N, Ito S, Kusumoto Y, Fujita T, Ishikawa S, Sumida T, Sekiya M. Somatostatinoma of the duodenum. Cancer. 1979;44:2273-2279. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | Tanaka S, Yamasaki S, Matsushita H, Ozawa Y, Kurosaki A, Takeuchi K, Hoshihara Y, Doi T, Watanabe G, Kawaminami K. Duodenal somatostatinoma: a case report and review of 31 cases with special reference to the relationship between tumor size and metastasis. Pathol Int. 2000;50:146-152. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Blaser A, Vajda P, Rosset P. [Duodenal somatostatinomas associated with von Recklinghausen disease]. Schweiz Med Wochenschr. 1998;128:1984-1987. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Moayedoddin B, Booya F, Wermers RA, Lloyd RV, Rubin J, Thompson GB, Fatourechi V. Spectrum of malignant somatostatin-producing neuroendocrine tumors. Endocr Pract. 2006;12:394-400. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 12. | Colovic R, Micev M, Grubor N, Radak V. [Somatostatinoma of the Vater's papilla in a patient with von Recklinghausen's disease]. Vojnosanit Pregl. 2007;64:219-222. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 13. | Tjon A, Tham RT, Jansen JB, Falke TH, Lamers CB. Imaging features of somatostatinoma: MR, CT, US, and angiography. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1994;18:427-431. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 14. | Konomi K, Chijiiwa K, Katsuta T, Yamaguchi K. Pancreatic somatostatinoma: a case report and review of the literature. J Surg Oncol. 1990;43:259-265. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 15. | Wynick D, Williams SJ, Bloom SR. Symptomatic secondary hormone syndromes in patients with established malignant pancreatic endocrine tumors. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:605-607. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 16. | Anene C, Thompson JS, Saigh J, Badakhsh S, Ecklund RE. Somatostatinoma: atypical presentation of a rare pancreatic tumor. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:819-821. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 17. | Guo M, Lemos LB, Bigler S, Baliga M. Duodenal somatostatinoma of the ampulla of vater diagnosed by endoscopic fine needle aspiration biopsy: a case report. Acta Cytol. 2001;45:622-626. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 18. | Oberg K, Eriksson B. Endocrine tumours of the pancreas. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;19:753-781. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 19. | Krausz Y, Bar-Ziv J, de Jong RB, Ish-Shalom S, Chisin R, Shibley N, Glaser B. Somatostatin-receptor scintigraphy in the management of gastroenteropancreatic tumors. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:66-70. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 20. | O’Brien TD, Chejfec G, Prinz RA. Clinical features of duodenal somatostatinomas. Surgery. 1993;114:1144-1147. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 21. | Green BT, Rockey DC. Duodenal somatostatinoma presenting with complete somatostatinoma syndrome. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;33:415-417. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 22. | Chamberlain RS, Canes D, Brown KT, Saltz L, Jarnagin W, Fong Y, Blumgart LH. Hepatic neuroendocrine metastases: does intervention alter outcomes? J Am Coll Surg. 2000;190:432-445. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 23. | Harris GJ, Tio F, Cruz AB Jr. Somatostatinoma: a case report and review of the literature. J Surg Oncol. 1987;36:8-16. [Cited in This Article: ] |