INTRODUCTION

Peliosis hepatis (PH) was first reported in the German literature in 1861 by Wagner, and named by Schoenlank in 1916[1]. It is a rare condition characterized by multiple small cystic blood-filled spaces from 1 mm to several centimeters in diameter in the hepatic parenchyma, resulting from the focal rupture of sinusoidal walls[2]. The etiology of PH is still unknown. Sinusoidal obstruction, hepatocellular necrosis, and direct injury to the sinusoidal barrier seem to be the most likely mechanism in adults[3]. PH is usually associated with chronic pathologic conditions, including cystic fibrosis, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection[4,5]. PH has also been reported after prolonged use of anabolic steroids (e.g. azathioprine[6], 6-thioguanine, and 6-mercaptopurine[7]) and oral contraceptives[8]. PH varies from minimal asymptomatic lesions to larger massive lesions that may present with cholestasis, liver failure, portal hypertension, avascular mass lesion, or even spontaneous rupture[9]. Here, we report a case of a 20-year-old male patient with aplastic anemia who presented with hemoperitoneum. This patient had received long-term treatment with oxymetholone, and his imaging findings and extraphysiological changes were consistent with spontaneous hepatic rupture with PH. The patient was salvaged from a life-threatening hemorrhage by performing a right hemihepatectomy.

CASE REPORT

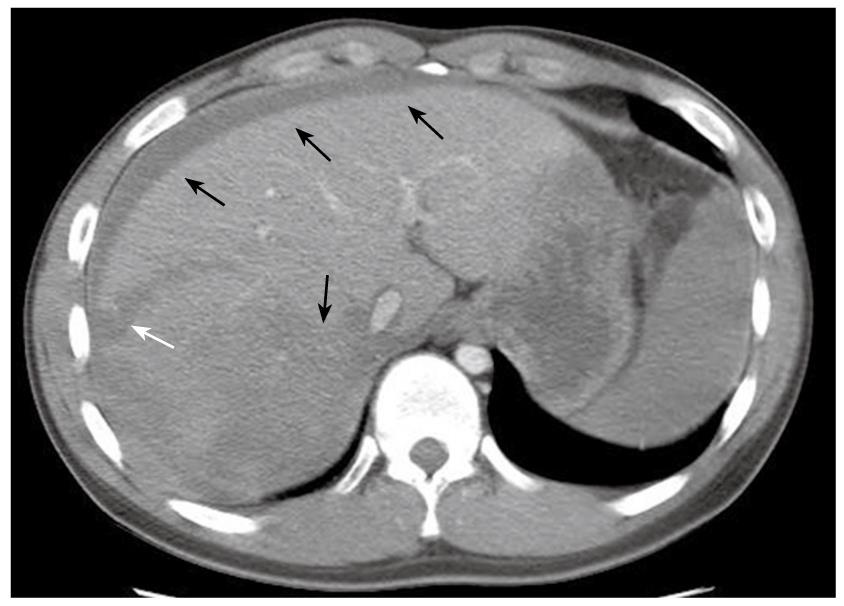

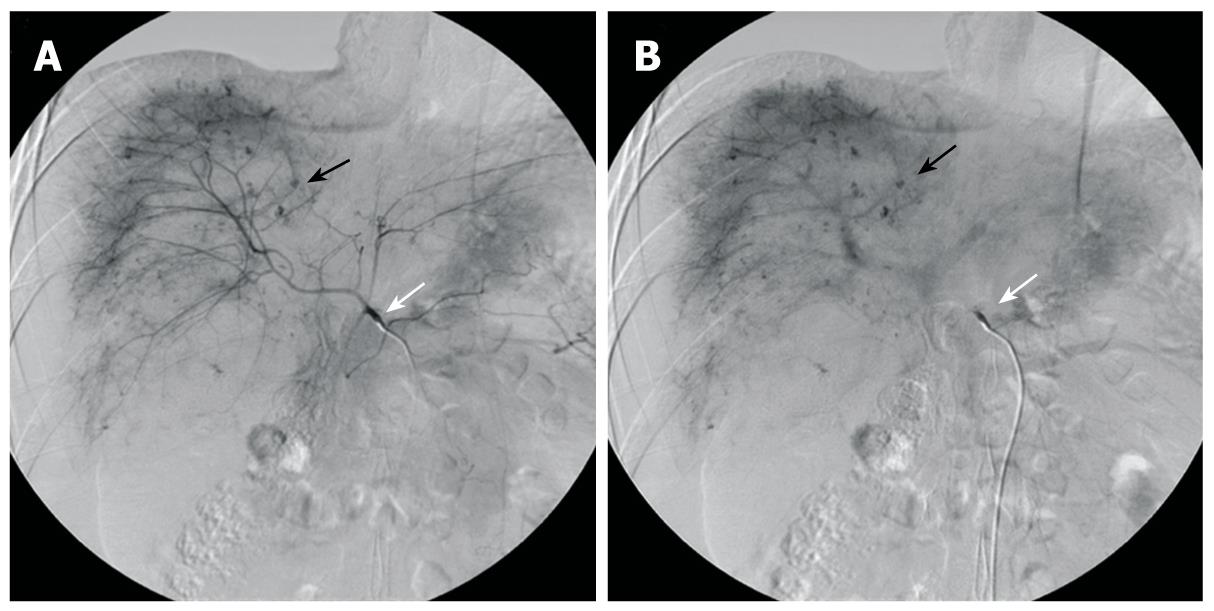

The patient was a 20-year-old male who had been diagnosed with aplastic anemia 8 years previously and had received long-term anabolic steroid therapy. He presented with complaints of pain in the abdomen for one day and a seizure attack without any previous episode. The vital signs at presentation were blood pressure 84/44 mmHg, heart rate 140 beats/min, respiratory rate 24 breaths/min, and body temperature 36°C. The laboratory findings were white blood cell count 5.1 × 109/L (normal 4 × 109 - 10 × 109/L), hemoglobin 3.01 mg/dL (normal 13.1-17.5 g/L), hematocrit 24.2% (normal 39%-52%), platelet count 38 × 109/L (normal 140 × 109 - 400 × 109/L), total bilirubin 1.287 mg/dL (normal < 1.3 mg/dL), alkaline phosphatase 145 IU/L (normal < 220 IU/L), alanine aminotransferase 495 IU/L (normal < 43IU/L), aspartate aminotransferase 332 IU/L (normal < 38 IU/L), and prothrombin time 17.1 s (normal 11-15 s). Computed tomography (CT) of the brain was taken in the emergency department and revealed no specific abnormality, but the patient suffered from 3 more seizure attacks and became rapidly hypotensive and tachycardic, with abdomen distended and tense. The patient received a red blood cell (RBC) transfusion and fluid resuscitation. Abdominal and pelvic CT showed a laceration of the liver in the right lobe inferior portion and a moderate amount of hemorrhage (Figure 1). Suspecting spontaneous liver rupture with hemoperitoneum, the patient was transferred to the angiography unit for an emergency angioembolization of the right hepatic artery. The angiography showed multiple contrast filling small round lesions predominantly in the right hemiliver (Figure 2A). The right hepatic artery was selected, and gelform embolization was attempted. On the venous phase angiogram, the peripheral portion of the right lobe of the liver was successfully embolized (Figure 2B). However, the patient continued to deteriorate, and hepatic and/or portal venous bleeding was suspected. An emergency exploratory laparotomy was performed.

Figure 1 CT of the abdomen showing laceration of the liver right lobe inferior portion (white arrow), with hyperdense fluid in the peritoneal cavity and liver parenchyma, suggesting acute blood collection in these areas (black arrows).

Figure 2 Preoperative selective hepatic angiography.

A: Selective angiography of the celiac trunk (white arrow) shows hemorrhagic spots (black arrow) in hepatic parenchyma at the arterial phase Note: Lesions are mainly distributed in the right hemiliver; B: Angiogram at the portal venous phase shows the lesions with delayed wash-out (black arrow).

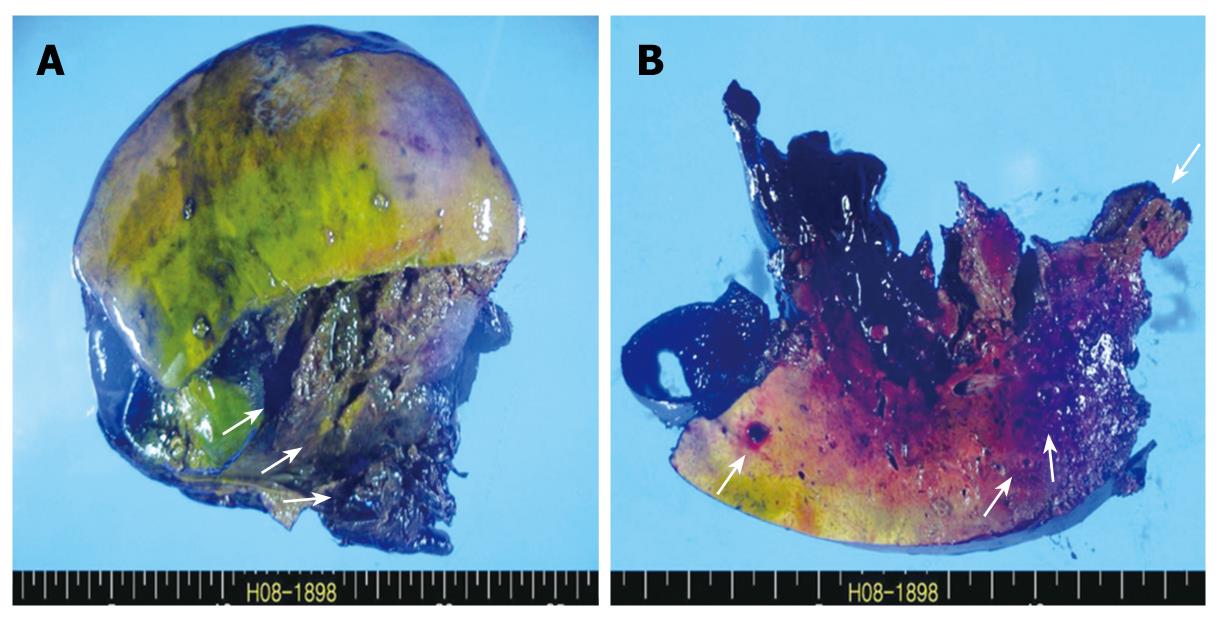

Under general anesthesia, the patient was placed in the supine position. A bilateral subcostal incision was made and deepened to the peritoneum. On entering the peritoneal cavity, profuse hemoperitoneum was noted, and the liver was found to be lacerated on the right posterior sector. The Pringle maneuver was performed, but failed to lessen the bleeding. An urgent right hemihepatectomy was performed by the Kelly-clamp crushing method and the finger-fracture technique. After hepatectomy was done, the right upper quadrant was packed with a laparotomy gauze pad, and the peritoneal cavity was thoroughly examined. The remaining left hemiliver did not show gross abnormality nor did the other intraperitoneal organs. After the peritoneal cavity was irrigated with a warm saline solution, the packed gauze pad was removed and the cut surface was examined for further bleeding. Only minimal oozing was noted. Two closed suction drains were inserted at the hepatic cut surface, and the abdominal wall was closed layer by layer. A resected specimen showed extensive necrosis and hemorrhage and the cut surface of the liver parenchyma revealed small blood-filled cystic lesions (Figure 3A and B). The operation required 7 h, and 28 pints of leukoreduced RBC were transfused. The systolic blood pressure ranged from 90 mmHg to 130 mmHg throughout the operation.

Figure 3 Gross findings.

A: Resected specimen shows extensive necrosis and hemorrhage (arrows); B: Cut surface of the liver parenchyma reveals small blood-filled cystic lesions (arrows).

Postoperatively, the patient was transferred to the intensive care unit and observed closely. When stable, the patient was admitted to the general ward on the 10th postoperative day, and oral intake was resumed. The drains were removed on the 20th postoperative day. The patient’s vital signs were stable until the 17th postoperative day when body temperature began to rise abruptly up to 38.5°C. Follow-up CT revealed an intraperitoneal abscess at the hepatectomy site. CT-guided percutaneous drainage was performed, and the patient’s fever subsided with antibiotic therapy. The patient was discharged from hospital on the 46th postoperative day. The most recent follow-up was on the 13th postoperative month, and the patient was in good condition without significant complication from the surgery or PH.

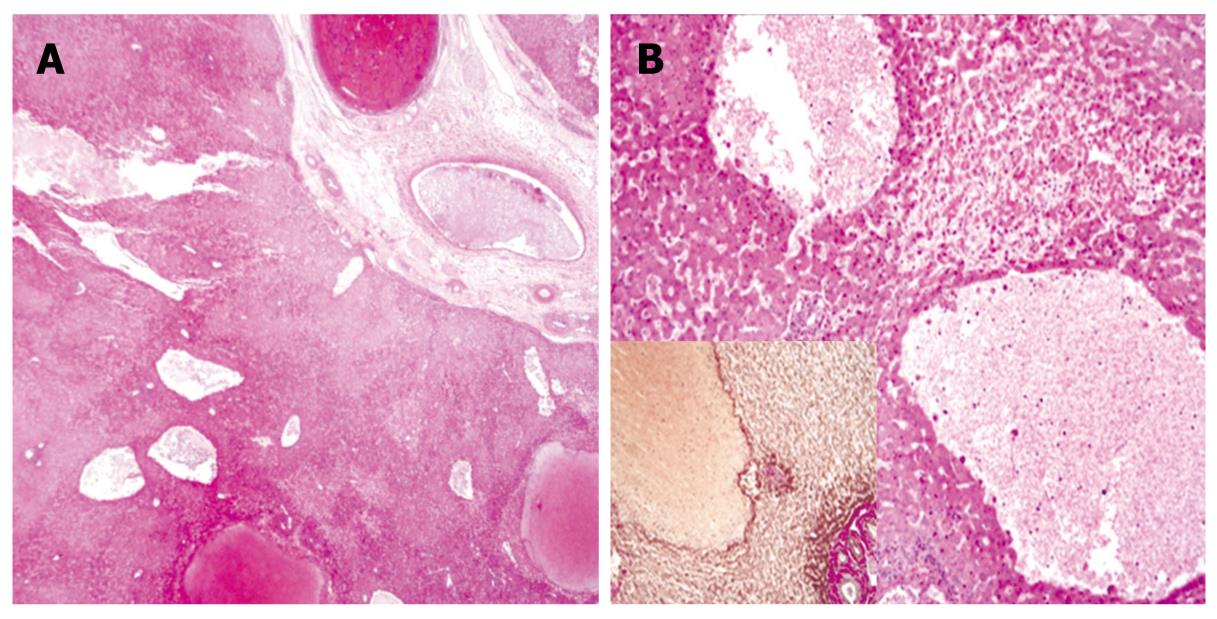

The diagnosis of PH was determined from preoperative angiographic findings and histological features. Selective angiography of the celiac trunk showed hemorrhagic spots in the right hepatic parenchyma at the arterial phase with delayed washout at the portal venous phase. Microscopically, there were variable sized blood-filled cystic spaces, and hemorrhagic necroses were present adjacent to the peliotic spaces without lining endothelium (Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 4 Microscopic findings.

A: Low magnification view shows variable-size, blood-filled cystic spaces (HE, × 10); B: High magnification view shows hemorrhagic necrosis in areas adjacent to peliotic spaces without lining endothelium (HE, × 100); Inset: immunohistochemical staining for reticulin (× 100).

DISCUSSION

Peliosis is an abnormality of the reticuloendothelial system and most commonly involves the liver. Occasionally, this condition may occur in the spleen and the bone marrow. Peliosis has mostly been reported in adult patients associated with chronic infections such as HIV[10] or the use of specific drugs[6,7,11]. In many cases, removal of the causative agent had caused regression of the disease[12].

The exact pathogenesis of peliosis is unknown. PH is characterized by blood-filled cystic spaces from a few millimeters to 1 cm in diameter, but can reach up to 4 to 5 cm. Two morphological patterns of PH were described by Yanoff et al[13]. The parenchymal pattern is characterized by irregular blood-filled spaces, lined by fibrous tissue rather than the endothelium, which neither communicate with the central veins nor compress adjacent parenchymal cells. Instead, they associate with many areas of focal necrosis in the surrounding hepatic tissue. The phlebectatic pattern, the second morphological type, shows minimal hepatocyte necrosis. The regularly spherical, centrilobular blood-filled spaces are lined by endothelial cells and/or fibrotic tissue and freely communicate with hepatic sinusoids. They are an integral part of the central vein, causing compression of the adjacent parenchymal cells, and they contain mural fibrin clots. However, Zak[1] considered these 2 morphological patterns to be one process, initiated by focal necrosis of the liver parenchyma, which transforms into an area of hemorrhage (parenchymal pattern). This pattern may progress to fibrous wall formation and endothelial lining around the hemorrhage (phlebectatic pattern), or it may heal by the resorption of blood. The phlebectatic pattern may heal by fibrin deposition, thrombosis, and sclerosis of vascular spaces. It has also been noted that a hyperplastic hepatocyte may be prolapsed into a terminal hepatic venule in anabolic steroid-induced peliosis. The theory that toxic substances may induce peliosis is supported by the finding of increased endothelial cell permeability with numerous RBCs in the space of Disse[14]. In the current case, the toxic substance that affected the sinusoidal wall was suspected to be the anabolic steroid oxymetholone, and the morphological characteristics were consistent with the parenchymal pattern. Degott et al[15] also reported that peliosis could be secondary to fibrous thickening of the hepatic venule, possibly due to azathioprine in patients who had taken the drug long-term.

Eising et al[16] reported an increased tendency toward liver rupture following blunt trauma in patients with PH. In the present case, the patient had no trauma history, and the cause of the seizure attack was believed to be hemorrhagic shock induced by spontaneous liver rupture. In addition, the patient’s usual platelet count was within the range of 40 × 109/L to 70 × 109/L, and the platelet count just prior to hepatic rupture was 43 × 109/L. To our knowledge, there has been no reported case of spontaneous liver rupture with this platelet level in the English literature. On the basis of these findings, we believe that the cause of spontaneous hepatic rupture in this patient was PH, and it was not the result of liver trauma or thrombocytopenia.

Interestingly, although systemic conditions were thought to be the cause of PH, the distribution of lesions within the liver was usually unilobar, favoring the right hemiliver. As far as we know, there has been no published report in the English literature on PH that mentions a preference in location. However, reported cases of liver rupture in PH patients are more common in the right lobe. Adam et al[17] and Toth et al[18] reported cases of PH rupture located in the left lobe of liver. But in other cases, the right lobe of the liver was the location of rupture[9,19-22], including the current case. Although Saatci et al[23] reported a case of PH with multiple foci involving both right and left lobes by magnetic resonance imaging, the location of PH in most cases was unilobar, which may be explained by the distribution of hepatic blood flow. However further research is needed to verify the cause of differential distribution of PH rupture, as more case studies are reported. At the very least, it can be postulated that PH of the liver is a progressive disease that occurs in one lobe first, then extends to the whole liver, and hepatic rupture is distributed along with lesions.

PH is difficult to recognize, and the diagnosis often is missed or delayed because its appearance on radiological imaging is suggestive of a neoplasm or multiple abscesses. An ultrasound scan may show hypoechoic areas involving the liver with intraperitoneal fluid collection and a normal Doppler signal[24]. Occasionally, only subtle inhomogeneity is seen in the liver, which can also be seen in other diffuse liver parenchymal diseases. A contrast enhancement CT scan of the liver may show small lesions of a few millimeters to 1 to 4 cm in diameter. The lesions typically are hypodense in early arterial phase scans and enhanced in late venous phase. The CT appearance of PH can be difficult to differentiate from multiple abscesses, hemangiomatosis, and metastases. The diagnosis of PH on an angiography is made by visualizing multiple small accumulations of contrast material in the late arterial phase, which persists into the venous phase. This can be confused with irregular tumor vessels in focal nodular hyperplasia and adenomas. However, it is unclear if the angiography offers better diagnostic information than ultrasonography. In the current case, an emergency CT failed to show specific changes of PH other than that of hemoperitoneum caused by hepatorrhexis, and an angiogram was necessary to arrive at the diagnosis. A definitive diagnosis of PH was made from histological findings. A percutaneous needle biopsy can also be used to confirm the diagnosis. However, even when ultrasound-guided, the procedure has a high risk of a life-threatening hemorrhage[25]. Consequently, a laparotomy appears to be the more appropriate procedure when tissue confirmation is needed because it permits assessment of the macroscopic appearance of peliosis, and a liver biopsy can be performed with adequate hemostasis.

There is no specific treatment for PH. Hepatic artery embolization or partial hepatectomy has been reported[8,26]. Emergency liver transplantation is the ultimate treatment in cases of imminent liver failure. The natural course of PH is not well known. Reports have described outcomes ranging from spontaneous resolution to hepatic failure or fatal intraperitoneal hemorrhage. Some reports have described the resolution of PH after withdrawal of causative drugs or after treatment of the associated conditions[12,26,27]. In other reports, patients presenting in fulminant hepatic failure eventually died. Fatal intraperitoneal hemorrhage has also been reported as another complication[9,28,29]. In summary, PH is an important disorder for consideration in the differential diagnosis of liver masses presenting acutely. PH is most often asymptomatic; in symptomatic patients, surgery should be reserved for cases when hemorrhage becomes life-threatening. Familiarity with imaging characteristics and awareness of this condition as a cause of hepatomegaly, hepatic failure, hepatic rupture, and hepatic hemorrhage can help in the early diagnosis of PH. Early removal of the known inciting agent may cause regression of this disease and prevent catastrophic complications. PH should be considered in all patients with known risk factors and presenting with typical morphological changes or hepatic mass, especially when the cause of the sudden onset of intraperitoneal hemorrhage is obscure. Although spontaneous regression of PH can occur in some patients, timely recognition and early treatment are essential to prevent life-threatening complications from the disease.