INTRODUCTION

Mesenteric lipodystrophy is an uncommon diagnosis with few, if any, symptoms at presentation. Only 200 cases have been reported in the world literature[1]. These cases mirror the presentation and symptoms of this case. Therefore, the diagnosis requires the astute clinical suspicion of the surgeon, radiologist, and pathologist, as it may resemble other diseases which require different therapeutic approaches. Diagnosis is usually achieved through laparotomy performed for a mesenteric mass with lipomatous characteristics. The first report is attributed to Jura[2], an Italian surgeon, who described a condition of "retractile sclerosing mesenteritis" in 1924. The term was reprised by Durst[3], who reviews 68 cases previously described in the literature and defines it as a benign disease. Today most articles describe the pathologic condition as "sclerosing mesenteritis", and divide it into three major phases, each regarding a progressively worsening state. The pathologic findings begin with fat necrosis and end with regenerative fibrosis. Within this progress of disease state, fat necrosis predominates in the first step, therefore called mesenteric lipodystrophy. This is then followed by mesenteric panniculitis, characterized by intense inflammatory reaction, and lastly by retractile mesenteritis, when fibrosis becomes the main feature.

CASE REPORT

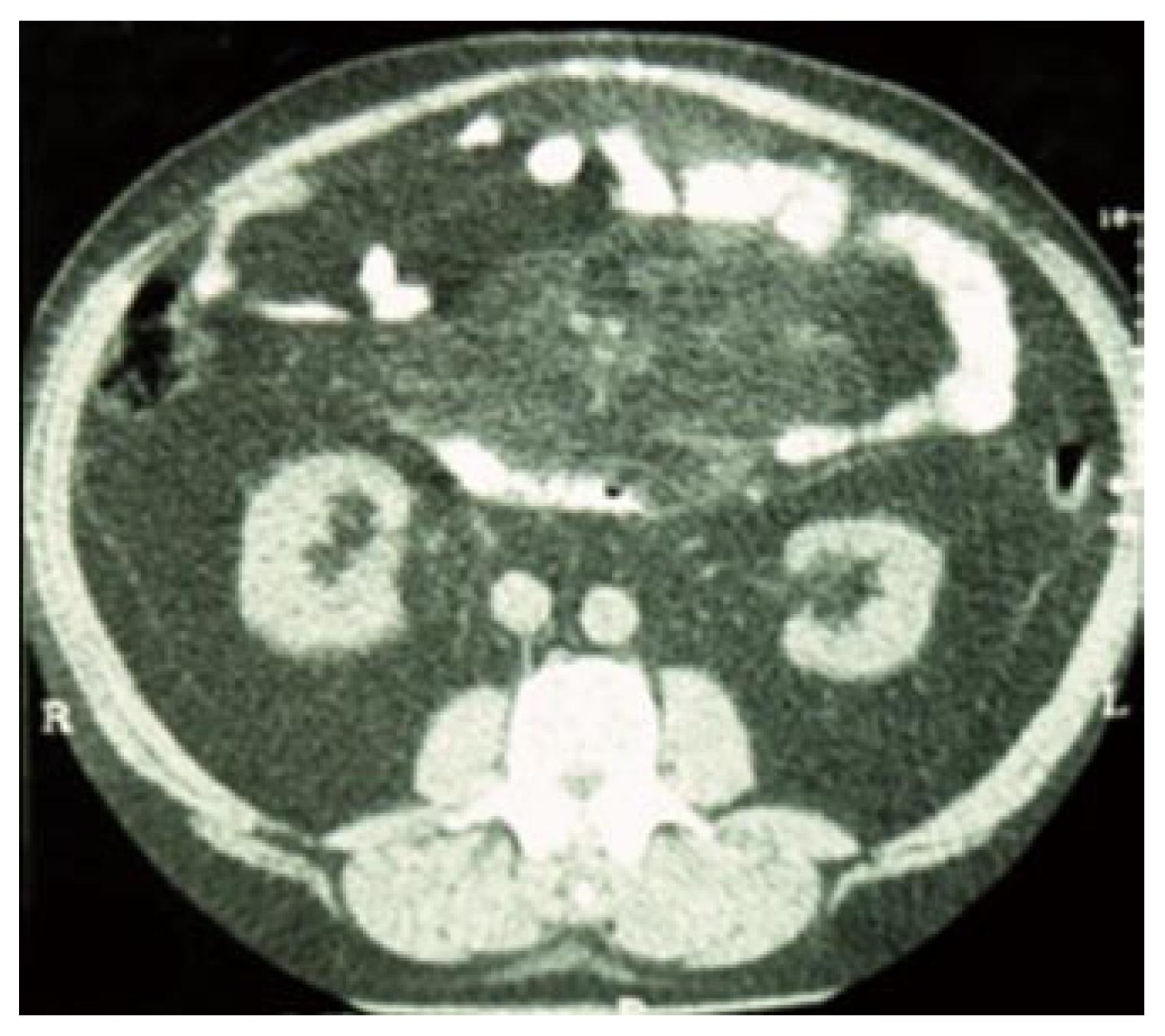

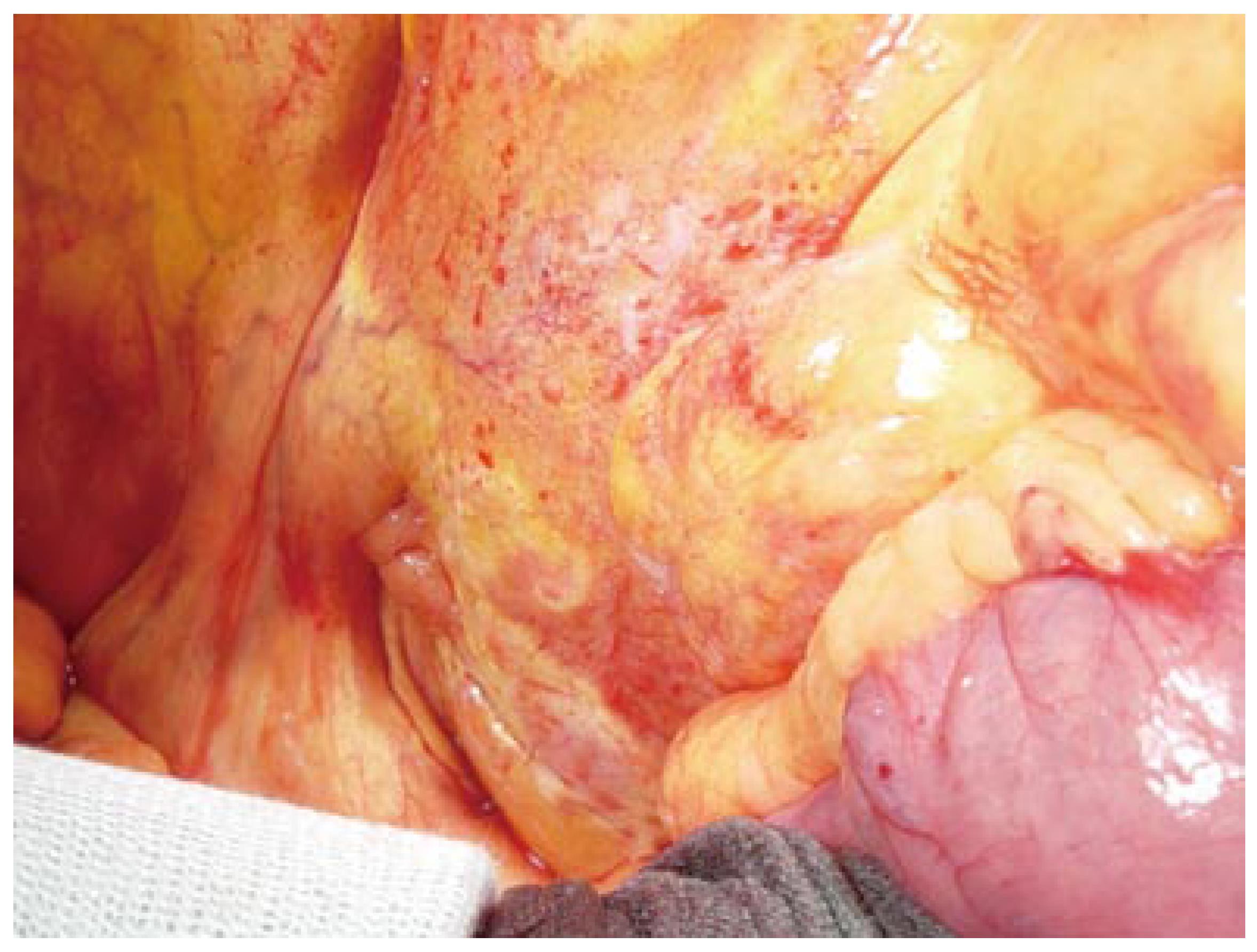

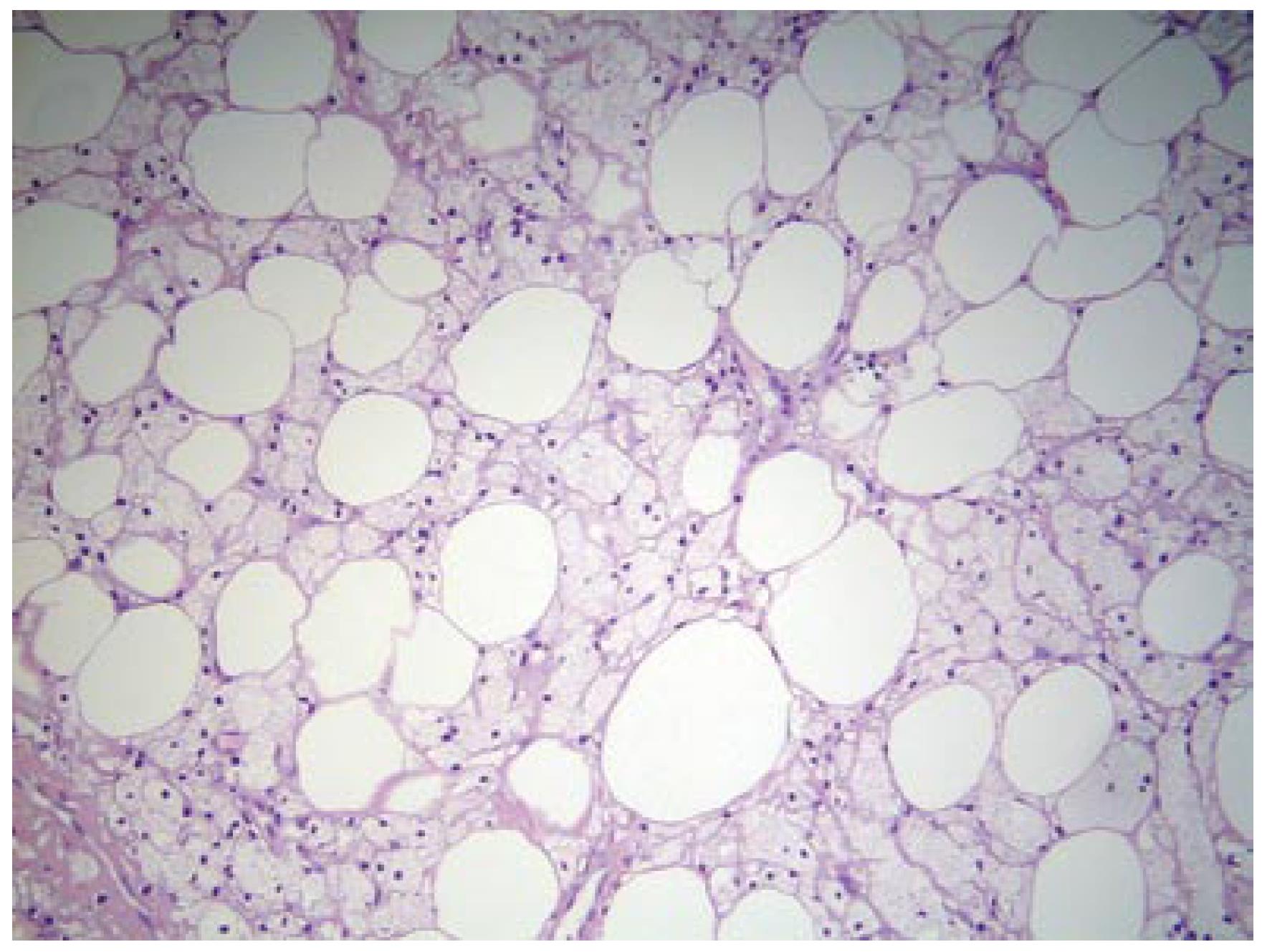

An obese (body mass index = 41), 56-year old Caucasian man underwent laparoscopy for the repair of an umbilical hernia (> 3 cm). On exploration chylous ascites was noted in the pouch of Douglas and taken for examination. Because of the patient's obesity no mass or other abnormalities were noted, with the exception of ceruleus stains on the surface of the mesentery, at first attributed to an unknown previous pancreatitis. A laparoscopic repair was performed, using a polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) mesh. The recovery was uneventful with dismissal on post operative day five. The patient did have chylous drainage in the first two days which then ceased by dismissal. Cytological and chemical examination of the fluid was negative for malignant cells, even though mononuclear inflammatory cells with enlarged cytoplasm were noted. Abdominal ultrasound and blood chemistry were normal, comprising amylase, lypase, lipidic asset, carcino-embryonal antigen (CEA) and Ca 19-9. After a month, a follow-up computed tomography (CT) scan (Figure 1) revealed hyperdensity of mesenteric fat, with regular margins, and radiological characteristics of a mesenteric lipoma (8 cm wide). Exploratory laparotomy was then performed to exclude definitely any malignancy. The mass was biopsied, however a complete removal was impossible due to its encasement of the superior mesenteric vessels (Figure 2). The ileum showed chronic ischemic condition with scars on the serosal surface. Macro-biopsies were performed which excluded neoplastic origin and diagnosed fatty necrosis, with scarce fibrotic component, adipose cells with foamy cytoplasm, infiltration of lipid-laden macrophages and foreign body giant cells (Figure 3). The patient was asymptomatic in the next six months, without any medical therapy, and did not complain of any digestive discomfort. The follow-up CT after three months was unchanged, except for a minimal reduction in the diameter of the mesenteric enlargement.

Figure 1 CT scan visualizing a mesenteric lipoma-like mass.

Figure 2 Intraoperative view of pseudonodular thickening of the mesentery.

Figure 3 Mesenteric adipose tissue showing lipid necrosis and foamy macrophages (HE, x 10).

DISCUSSION

A nosological classification has been recently proposed[4] for this rare pathology with unknown origin, defining under the word of "sclerosing mesenteritis", a disease previously described as mesenteric panniculitis, retractile mesenteritis, isolated lipodystrophy, mesenteric lipogranuloma, mesenteric manifestation of Weber-Christian disease, etc. Only three large series have been collected in Literature, one by Durst[3], one by Kipfer[5] and one more recently by Emory[4] of 68, 53 and 42 cases, respectively. Still this disease is largely unknown to many surgeons and pathologists. It usually affects males (2-3:1), in the fifth or sixth decade of life (age range 20-80 years), and might take on different clinical aspects. In almost half of the cases (as in our patient) the mass is incidentally discovered during abdominal surgery (i.e., during cholecystectomy). The remaining patients might complain of various degrees of intestinal obstruction, from post-prandial discomfort to acute occlusion. Other uncommon clinical findings may be fever, protein, losing enteropathy or abdominal mass. The biochemistry is mostly unhelpful in diagnosis. CT scan appearance varies from increased attenuation ("misty mesentery") to solid soft-tissue mass, which might envelope the mesenteric vessels preserving a fatty area around ("fat ring sign")[6,7]. Other tumors of the mesentery may show a similar radiologic appearance, like lipoma, lymphoma, carcinoid tumor, carcinomatosis or tubercolosis, mesothelioma, edema or hematoma (from cirrhosis, trauma, hypoalbuminemia, heart failure or vasculitis)[8]. Percutaneous needle aspiration or biopsy can give a hint to diagnosis, but generally laparotomy and surgical biopsy is required. More recently laparoscopic biopsy has been described[9,10], but a pre-operation suspicion is mandatory, given, for example, by a CT scan. In our case, obesity (hiding the diffuse thickness of the mesentery) and the peritoneal aspect (mimicking that of a pancreatitis) misled laparoscopic diagnosis. A CT scan, performed after dismissal, led to laparotomy, in order to obtain a radical excision of the described mass. Intraoperative findings might be a diffuse thickening of the mesentery, a single tumor, multiple tumors or also a various mix of the nodular and hypertrophic components. Also the mesocolon may be involved, as well as, rarely, mesoappendix, peripancreatic area, omentum and pelvis. Its gross appearance explains how easy it is to mimick many other intra-abdominal neoplastic diseases. Histology displays different grades of involvement. Lipodystrophy is characterized by mesenteric infiltration by lipid-filled macrophages in the narrow septa inside the adipose tissue, as inflammation increases (panniculitis) lymphocytic infiltrate and lipid cystic necrosis can be noted. The last stage is distinguished by a diffuse presence of necrosis and fibrosis that contribute to tissue retraction as seen in retractile mesenteritis. Also calcifications and giant multinucleated cells have been seen in some cases. In the case presented, macrophage infiltration was the main feature, even if a component of fatty necrosis and fibrosis was evidenced. Haematoxylin and eosin stain is generally enough to provide a correct diagnosis, but also immunochemistry might prove useful in some cases (between antibodies' panel nuclear beta-catenin has proved interesting)[11]. The differential diagnosis comprises foreign body reaction (more fibrosis and fewer lipid laden macrophages) and Weber-Christian disease (predominantly localized in the subcutaneous tissue and with enhanced lymphocytic infiltrate)[12]. Lipomatosis, lymphoma and retroperitoneal fibrosis have quite different microscopic features, and no fatty necrosis[13]. Although the aetiology remains obscure, association with other diseases has been described. AIDS[14], non-Hodgkin lymphoma[15], tuberculitis[1], cholesterol ester storage disease[16] have been found together with sclerosing mesenteritis. Drug therapy is not standardized, and should be based on the stage of the disease. In the first stage, when fat necrosis is predominant, authors agree not to treat the disease as it can regress spontaneously. Chronic inflammation requires therapy based on corticosteroids and various types of immunosuppressants. Good results are reported with cyclophosphamide, colchicine, azathioprine and also with oral progesteron[17]. As intense fibrosis appears, bowel obstruction may occur. Intestinal resections, bypasses or neostomy might be required[18,19].

In summary, diagnosis of this unspecific, benign inflammatory disease is a challenge, both for the radiologist, surgeon and pathologist. Some authors[20] suggest that this condition might be more common than reported. In fact, as Poniachik et al[21] has supposed, the suspect of sclerosing mesenteritis has to be arisen in order to prevent such conditions to be catalogued as "unspecific inflammatory process". Since we also met the difficulty in diagnosis by laparoscopic means, especially for large masses in obese patients, we acknowledge that laparotomy is required to achieve complete removal or at least a macro-biopsy of the mass, as pathologic examination on frozen section might be incomplete, and radiology is unhelpful.