Published online Jul 28, 2006. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i28.4549

Revised: September 22, 2005

Accepted: July 10, 2005

Published online: July 28, 2006

AIM: To investigate whether the degree of rectal distension could define the rectum functions as a conduit or reservoir.

METHODS: Response of the rectal and anal pressure to 2 types of rectal balloon distension, rapid voluminous and slow gradual distention, was recorded in 21 healthy volunteers (12 men, 9 women, age 41.7 ± 10.6 years). The test was repeated with sphincteric squeeze on urgent sensation.

RESULTS: Rapid voluminous rectal distension resulted in a significant rectal pressure increase (P < 0.001), an anal pressure decline (P < 0.05) and balloon expulsion. The subjects felt urgent sensation but did not feel the 1st rectal sensation. On urgent sensation, anal squeeze caused a significant rectal pressure decrease (P < 0.001) and urgency disappearance. Slow incremental rectal filling drew a rectometrogram with a “tone” limb representing a gradual rectal pressure increase during rectal filling, and an “evacuation limb” representing a sharp pressure increase during balloon expulsion. The curve recorded both the 1st rectal sensation and the urgent sensation.

CONCLUSION: The rectum has apparently two functions: transportation (conduit) and storage, both depending on the degree of rectal filling. If the fecal material received by the rectum is small, it is stored in the rectum until a big volume is reached that can affect a degree of rectal distension sufficient to initiate the defecation reflex. Large volume rectal distension evokes directly the rectoanal inhibitory reflex with a resulting defecation.

- Citation: Shafik A, Mostafa RM, Shafik I, EI-Sibai O, Shafik AA. Functional activity of the rectum: A conduit organ or a storage organ or both? World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12(28): 4549-4552

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v12/i28/4549.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v12.i28.4549

The rectum, a continuation of the colon, acts to propel the stools to the exterior and is thus considered as a conduit[1-3]. However, its function as a conduit for stools is controversial[4-6]. Stools are palpable on digital rectal examination (DRE) in many healthy volunteers who do not feel the desire to defecate[4-6]. Neil and Rampton[5] reported that stools are present in the rectum in 31% of normal subjects. Stools are also palpated by DRE in the lower rectum of healthy subjects and appear in the radiograms. Our studies have shown that the rectum stores the stools if the quantity is small, while functions as a conduit if the stools received from the sigmoid colon are voluminous. A small stool volume reaching the rectum from the sigmoid colon probably does not affect rectal distension or evoke the rectoanal inhibitory reflex (RAIR). In such case the stools accumulate in the rectum until they reach a big distending volume that initiates the RAIR. On the other hand, big distending volumes of the stools propelled from the sigmoid colon appear to be able to initiate the RAIR and expel the stools without storage in the rectum. Accordingly, the rectal function as a storage organ or a conduit appears to depend on the volume of fecal matter passing from the sigmoid colon to the rectum and consequently on the degree of rectal distension the volume creates.

We thus hypothesized that rectal function as a conduit or reservoir would depend on the degree of rectal distension. This hypothesis was investigated in the current study.

Twenty-one healthy volunteers (12 men, 9 women, mean age 41.7 ± 10.6 years, range 29-56 years) participated in the study. They were fully informed about the nature of the study, the tests to be done, and their role in the study. They had no anorectal complaint either in the past or at the time of enrolment. The mean stool frequency was 8.6 ± 1.2 times per week (range 8-11), being in accord with that of normal volunteers in our laboratory. Physical examination, including neurological assessment, was normal. Laboratory work was unremarkable. Sigmoidoscopy assured that the rectum was normal in all the subjects. The subjects gave an informed consent, and the study was approved by the Review Board and Ethics Committee of the Cairo University Faculty of Medicine.

The subject was instructed to fast for 12 h before the test, and the bowel was evacuated by saline enema. The rectum was distended by a thin polyethylene infinitely compliant balloon, 3 cm in diameter, which was attached to the end of a 10 F tube (London Rubber Industries Ltd, London, UK). The pressure measured within the balloon was considered to be representative of the rectal pressure. With the subject lying in the left lateral position and under no medication, the collapsed balloon was introduced into the rectum through the anus. The tube was connected to a strain gauge pressure transducer (Statham 23 bb, Oxnard, CA).

The anal and rectal pressures were separately measured with a saline-perfused tube. The 10 F tube with multiple side ports at its distal closed end was introduced through the anus for 2-3 cm to lie in the rectal neck (anal canal). Another tube was introduced for 8-10 cm to lie in the rectum. The tube was connected to a pneumohydraulic capillary infusion system (Arndorfer Medical Specialities, Greendale, WI), supplied with a pump that delivers saline solution continually via the capillary tube at a rate of 0.6 mL/min. The transducer outputs were registered on a rectilinear recorder (RS-3400, Gould Inc, Cleveland, OH). Occlusion of the recording orifice produced a pressure elevation of greater that 250 cm H2O/s.

Prior to anal and rectal pressure recording, the gut was allowed a 20-min period to adapt to the rectal balloon and the manometric tubes in the anal canal and rectum. We recorded the response of the rectal and anal pressures to 2 types of rectal balloon distension: rapid voluminous distension and slow gradual distension. The rectal balloon was filled with 200 mL of normal saline in 10 s for rapid filling, and with increments of 20 mL in 10 s for slow filling. The test was performed at rest and while the anal sphincters were squeezed. The subjects were asked to report the onset of awareness of "something" in the rectum (the first rectal sensation) and the urgent sensation to defecate.

To ensure reproducibility of the results, the tests were repeated at least twice in the individual subjects and the mean value was calculated. The results were analyzed statistically by the Student's t test and the values were given as mean ± SD.

The study was completed in all the subjects with no adverse side effects. The mean resting rectal pressure was 8.7 ± 0.9 cm H2O (range 8-10) and the mean anal pressure was 73.6 ± 4.6 cm H2O (range 65-79).

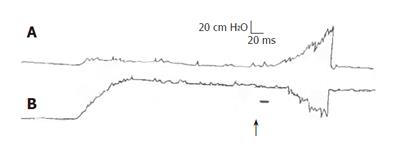

Rectal balloon distension with 200 mL of normal saline in 10 s resulted in a significant increase of the rectal pressure and a decrease of the anal pressure (Figure 1).The balloon was expelled to the exterior. The mean rectal pressure was 63.4 ± 8.2 cm H2O (range 56-82 cm H2O, P < 0.001) and the mean anal pressure was 22.4 ± 2.6 cm H2O (range 18-26 cm H2O, P < 0.01). The subjects felt the urgent sensation followed by balloon expulsion, but did not feel the first rectal sensation. When the subject upon feeling the urgent sensation, was asked to squeeze the anal sphincters for seconds, the mean anal pressure rose to 146.8 ± 16.2 cm H2O (range 128-166 cm H2O), resulting in disappearance of the urgent sensation and a significant decrease in the rectal pressure to 10.8 ± 1.1 cm H2O (range 8-12 cm H2O, P < 0.001). The balloon was not expelled but stored in the rectum. After a few seconds however, if the patient was asked not to squeeze the sphincters, the urgent sensation recurred and the balloon was expelled.

The test was reproducible with no significant difference (P < 0.05) in the recorded pressure values. There was also no significant difference between men and women.

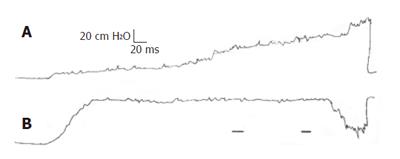

During rectal filling with a small volume (20 mL in 10 s), rectometrogram was produced (Figure 2). The curve showed a "tone limb" representing the rectal pressure as it increased during rectal filling, and an "evacuation limb" representing the rectal pressure during the process of balloon expulsion. The tone limb carried the points of incidence of the first rectal and urgent sensations while displaying a gradual incline until expulsion started.

The evacuation limb described a "curve" which was continuous with the tone limb. It was manifested at a variable distance after the urgent sensation and depended on the subject's desire to evacuate. The evacuation curve had an ascending limb rising slowly as a continuation of the tone limb, and a vertical descending limb (Figure 2).

The mean rectal balloon distending volume was 78.3 ± 16.6 mL (range 53-108 mL) at the first sensation and 152.6± 18.9 mL (range 106-182 mL) at the urgent sensation. The mean rectal pressure was 51.7 ± 9.8 cm H2O at the 1st rectal sensation and 62.9 ± 14.2 cm H2O at the urgent sensation, while the mean anal pressure was 70.6 ± 5.2 cm H2O and 18.7 ± 2.3 cm H2O, respectively (Table 1).

The aforementioned results were reproducible with no significant difference when the test was repeated in the individual subjects.

The rectum presumably receives stools from the sigmoid colon, either in a big volume affecting rapid voluminous distension of the rectum, or in small masses affecting gradual rectal distension. The current study could shed some light on the rectal function during the rapid voluminous distension and the slow gradual rectal distension.

Rapid voluminous rectal distension seems to evoke the recto-anal inhibitory reflex as is evident from the increased rectal and decreased anal pressures as well as from balloon expulsion. The subjects feel the urgent sensation but not the first rectal sensation which is normally felt in the gradual rectal distension. In such conditions, the rectum is considered as a conduit, conducting the stools directly from the colon to the exterior. It is likely that the big voluminous rectal distension induces stimulation of the rectal mechanoreceptors with a resulting initiation of the defecation reflex. In this case the rectum evacuates the received stools and remains empty, provided the circumstances are opportune for defecation.

Squeeze of the anal sphincters could abort the urgent sensation and affect waning of the desire to defecate. The mechanism needs to be further discussed. If circumstances are inopportune for defecation, sphincteric squeeze causes rectal relaxation mediated by the voluntary anorectal inhibition reflex[7]. However, after some time, the loaded rectum re-contracts probably due to re-stimulation of the rectal mechanoreceptors. If the desire to defecate is still opposed, the external sphincter contracts again. This process is repeated till either defecation is acceded to, or a prolonged contraction of the un-striped rectal detrusor tires out the striped short-contracting external anal sphincter which involuntarily relaxes leading to internal anal sphincter relaxation and opening of the rectal neck.

Slow incremental rectal filling does not affect rectal contraction until rectal filling reaches a large enough volume to stimulate the rectal mechanoreceptors and evoke the defecation reflex. During the period of slow gradual filling, the rectum presumably contains stools which are commonly palpated in some subjects during DRE. We postulate that in such cases the amount of stools received from the sigmoid colon is too small to stimulate the rectal mechanoreceptors or evoke the defecation reflex. The stools most probably continue to pile up in the rectum until an adequate volume is reached that stimulates the rectal mechanoreceptors and evokes the recto-anal inhibitory reflex. In such conditions, the stools may remain accumulated in the rectum for an extended period during which the rectum acts as a “storage” organ. We speculate that stool storage in the rectum may affect its consistency and act as a contributing factor in the genesis of constipation. The storage function of the rectum is apparently due to the adaptability of its smooth muscle to small volume rectal distension. This mechanism of “receptive relaxation” is similar to that occurring in the stomach.

In conclusion, the rectum has apparently 2 functions: transportation (conduit) and storage, both depending on the degree of rectal distension. If the fecal material received by the rectum is small, it is stored in the rectum until a big volume accumulated affects rectal distension sufficient to initiate the defecation reflex. However, stool storage in the rectum may be a contributing factor in the genesis of constipation. Large volume rectal distension evokes directly the recto-anal inhibitory reflex with a resulting defecation.

Margot Yehia assisted in preparing the manuscript.

S- Editor Guo SY L- Editor Wang XL E- Editor Liu WF

| 1. | Daniels EJ. Physiology of the colon. Colon and Rectal Surgery, 4th ed, Lippincott-Raven: Philadelphia 1998; 27-36. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Keighley MB, Williams NS. Constipation. Surgery of the Anus, Rectum and Colon. WB Saunders Co: London 1993; 609-638. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Guyton AC, Hall JE. The gastrointestinal tract. Human Physiology and Mechanisms of Disease. 6th, WB Saunders CO: London 1997; 511-536. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Goligher JC. Surgical anatomy and physiology of the anus, rectum, and colon. Surgery of the Anus, Rectum and Colon. 5th. Ballière Tindall: London 1984; 1-47. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Neil MC, Rampton DS. Is the rectum usually empty A quantitative study in subjects with and without diarrhea. Dis Colon Rectum. 1981;24:596-599. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 26] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Shafik A, Ali YA, Afifi R. Is the rectum a conduit or storage organ. Int Surg. 1997;82:194-197. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Shafik A, el-Sibai O. Rectal inhibition by inferior rectal nerve stimulation in dogs: recognition of a new reflex--the 'voluntary anorectal inhibition reflex'. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;13:413-418. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 16] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |