Published online May 1, 2004. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i9.1341

Revised: December 20, 2003

Accepted: January 9, 2004

Published online: May 1, 2004

AIM: To know the epidemiology and outcome of Crohn’s disease at King Khalid University Hospital, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia and to compare the results from other world institutions.

METHODS: A retrospective analysis of patients seen for 20 years (between 1983 and 2002). Individual case records were reviewed with regard to history, clinical, findings from colonoscopy, biopsies, small bowel enema, computerized tomography scan, treatment and outcome.

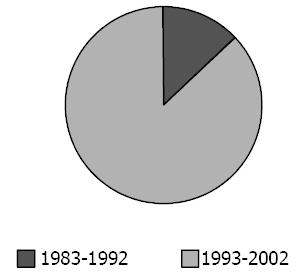

RESULTS: Seventy-seven patients with Crohn’s disease were revisited, 13% presented the disease in the first 10 years and 87% over the last 10 years. Thirty-three patients (42.9%) were males and 44 (57.1%) were females. Age ranged from 11-70 years (mean of 25.3 ± 11.3 years). Ninety-two (92%) were Saudi. The mean duration of symptoms was 26 ± 34.7 mo. The mean annual incidence of the disease over the first 10 years was 0.32:100000 and 1.66:100 000 over the last 10 years with a total mean annual incidence of 0.94:100000 over the last 20 years. The chief clinical features included abdominal pain, diarrhea, weight loss, anorexia, rectal bleeding and palpable mass. Colonoscopic findings were abnormal in 58 patients (76%) showing mostly ulcerations and inflammation of the colon. Eighty nine percent of patients showed nonspecific inflammation with chronic inflammatory cells and half of these patients revealed the presence of granulomas and granulations on bowel biopsies. Similarly, 69 (89%) of small bowel enema results revealed ulcerations (49%), narrowing of the bowel lumen (42%), mucosal thickening (35%) and cobblestone appearance (35%). CT scan showed abnormality in 68 (88%) of patients with features of thickened loops (66%) and lymphadenopathy (37%). Seventy-eight percent of patients had small and large bowel disease, 16% had small bowel involvement and only 6% had colitis alone. Of the total 55 (71%) patients treated with steroids at some point in their disease history, a satisfactory response to therapy was seen in 28 patients (51%) while 27 (49%) showed recurrences of the condition with mild to moderate symptoms of abdominal pain and diarrhea most of which were due to poor compliance to medication. Seven patients (33%) remained with active Crohn’s disease. Nine (12%) patients underwent surgery with resections of some parts of bowel, 2 (2.5%) had steroid side effects, 6 (8%) with perianal Crohn’s disease and five (6.5%) with fistulae.

CONCLUSION: The epidemiological characteristics of Crohn’s disease among Saudi patients are comparable to those reported from other parts of the world. However the incidence of Crohn’s disease in our hospital increased over the last 10 years. The anatomic distribution of the disease is different from other world institutions with less isolated colonic affection.

- Citation: Al-Ghamdi AS, Al-Mofleh IA, Al-Rashed RS, Al-Amri SM, Aljebreen AM, Isnani AC, El-Badawi R. Epidemiology and outcome of Crohn’s disease in a teaching hospital in Riyadh. World J Gastroenterol 2004; 10(9): 1341-1344

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v10/i9/1341.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v10.i9.1341

Crohn’s disease is a chronic recurrent inflammatory disorder of the bowel of unknown cause that can affect any gastrointestinal site from mouth to the anal canal. It results in long-term morbidity and the need for medical treatment and surgical interventions with resection of bowels. Slight increase in mortality plays significant demands upon healthcare resources[1,2]. Epidemiological studies have shown that Crohn’s disease tends to increase[3-5]. These may be due to improvement of diagnostic procedures and practices and increasing awareness of the disease. Crohn’s disease varies with geographical location[6-15]. Diet and genetic predisposition triggered by environmental factors may play a significant role[16].

The aim of this study was to know the epidemiology and outcome of Crohn’s disease at our institution and to compare the results with reports from other world institutions.

All patients attending the Gastroenterology Unit of King Khalid University Hospital, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia with a diagnosis of Crohn’s disease between 1983 and 2002 were enrolled into the study. Seventy-seven patients with Crohn’s disease were qualified (based on completeness of the data). The files of these patients were thoroughly reviewed from the time when the diagnosis of Crohn’s disease was made based on history, colonoscopic findings, colonic biopsies, small bowel enema and CT scan of abdomen up to the date of each patient’s last follow-up. Significant data collected included epidemiological points of Crohn’s disease patients, age and gender at presentation, smoking history, the common clinical features of the disease, diagnostic modalities used for confirmation of the disease and their corresponding results, laboratory tests at initial and last visits, current status of the patient, treatment protocols used, their responses to treatment and outcome of management.

Data were entered systematically into computer with Microsoft Excel. Statistical analyses and correlations were done using Stat Pac Gold analysis software. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

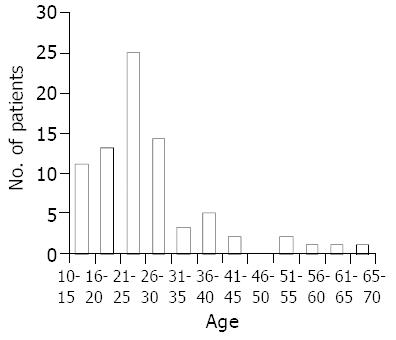

A total of 77 patients with Crohn’s disease over the last 20 years were reviewed. Ten (13%) patients presented the disease in the first 10 years and 67 (87%) patients over the last 10 years (Figure 1). Thirty-three (42.9%) patients were males and 44 (57.1%) were females. Age ranged from 11 to 70 years with a mean age of 25.3 ± 11.3 years. Seventy-one (92%) were Saudi nationals (Figure 2). The mean duration of symptoms was 26 ± 34.7 mo (range 1-180 mo). Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of all patients with Crohn’s disease.

| All patients | Active | On remission | |

| Number | 77 | 34 (44%) | 43 (56%) |

| Total males | 33 (42.9%) | 15 (44%) | 18 (42%) |

| Total females | 44 (57.1%) | 19 (56%) | 25 (58%) |

| Age (range), yr | 11-70 | 11-55 | 11-70 |

| Mean age, yr | 25.3 ± 11.3 | 22.9 ± 8.3 | 27.3 ± 13.2 |

| Nationality (Saudi/non-Saudi) | 71/6 | 32/2 | 39/4 |

The mean annual incidence of the disease in the first 10 years was 0.32:100000 and 1.66:100000 in the last 10 years with total a mean annual incidence of 0.94:100000 in the last 20 years.

Table 2 illustrates the chief clinical features of patients with Crohn’s disease, showing abdominal pain in 67 patients (87%), diarrhea in 60 (78%), weight loss in 41 (53%), anorexia in 22 (29%) and rectal bleeding in 19 patients (25%). Fifty eight percent of patients had abdominal tenderness and 10% had palpable mass while 42% had negative physical examination findings.

| All patients, n = 77 | Active Crohn's, n = 34 | Remission, n = 43 | |

| Abdominal pain | 67 (87) | 29 (85) | 38 (88) |

| Diarrhea | 60 (78) | 27 (79) | 33 (77) |

| Weight loss | 41 (53) | 23 (68) | 18 (42) |

| Anorexia | 22 (29) | 10 (29) | 12 (28) |

| Fever | 20 (26) | 8 (24) | 12 (28) |

| Rectal bleeding | 19 (25) | 5 (15) | 14 (32) |

| Normal physical examination | 32 (42) | 10 (29) | 22 (51) |

| Abdominal tenderness | 45 (58) | 24 (71) | 21 (49) |

| Palpable mass | 8 (10) | 3 (9) | 5 (12) |

Table 3 shows the colonoscopic, biopsy results, enteroclysis findings and CT scan results. Colonoscopy was abnormal in 58 patients (76%) showing features of ulcerations in 40 patients (52%), inflammation in 25 (33%), thickened mucosa in 18 (24%), pseudopolyps in 13 (17%) and nodularity in 8 (11%). Biopsy showed abnormal results in all patients with chronic inflammatory cell infiltration in 69 patients (90%), ulceration and granuloma in 31 patients (40%), crypt abscess in 19 (25%), edema in 15 (19.5%), granulations in 11 (14%) and goblet cell depletion in 10 (13%). Small bowel enema showed abnormal findings in 69 patients (89%) with ulceration in 34 (49%), narrowed lumen in 29 (42%), mucosal thickening in 24 (35%), nodularity in 18 (23%), loop separation in 15 (19%) and filling defect in 6 (8%). CT scan results showed abnormal findings in 68 patients (88%) with thickened loops in 45 patients (66%), small mesenteric nonspecific lymphadenopathy in 25 (37%), hypervascularity in 18 (23%) and presence of mass in 15 (19%).

| All patients | Active Crohn's | Remission | |

| Colonoscopy | n = 76 | n = 33 | n = 43 |

| Normal | 18 (24) | 8 (24) | 10 (23) |

| Abnormal | 58 (76) | 25 (76) | 33 (77) |

| Biopsy | n = 77 | n = 34 | n = 43 |

| Normal | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Abnormal | 77 (100) | 34 (100) | 43 (100) |

| Enteroclysis | n = 77 | n = 34 | n = 43 |

| Normal | 8 (11) | 5 (15) | 3 (7) |

| Abnormal | 69 (89) | 29 (85) | 40 (93) |

| CT scan | n = 77 | n = 34 | n = 43 |

| Normal | 9 (12) | 9 (26) | 0 |

| Abnormal | 68 (88) | 25 (74) | 43 (100) |

The anatomic distribution of Crohn’s disease in our patients was as follows, namely 16% had small bowel disease without colonic involvement, 78% had both small and large bowel disease and 6% had colitis alone.

Of the 77 patients, 55 were treated with steroids. A satisfactory response was seen in 28 patients (51%) while 27 (49%) showed recurrences of the condition, most of which were due to poor compliance to medication. Twenty-one (27%) patients however, did not receive steroids, of them seven (33%) remained with active Crohn’s disease.

Nine (12%) patients underwent surgery with resections of parts of their bowel, two (2.5%) with steroid side effects, 6 (8%) with perianal disease (e.g. fissure, sinuses or fistulae), and 3 (4%) with fistulae between the bowel and 2 (2.5%) with perianal fistulae.

Table 4 illustrates the comparison of the initial laboratory results in all patients with active Crohn’s disease and those with remission. Of these initial laboratory results, the hemoglobin level in patients with remission was statistically significantly higher than those patients with active Crohn’s disease (P value = 0.0118). Table 5 shows the comparison of initial and last follow-up laboratory results of 43 patients with remission. In patients with remission, the hemoglobin level was significantly increased from an initial level of 10.72 ± 2.12 g/L to 12.4 ± 1.78 g/L at the last follow-up (P value = 0.0001). Furthermore, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 49.5 ± 26.6 on the initial visit was significantly dropped to 29.9 ± 26.01 at the last follow-up (P value 0.0009). Whereas, in patients with active Crohn’s, there was no significant change in their laboratory results from initial to last follow-up (Table 6).

| All patients | Active Crohn’s | Remission | |

| WBC count | 9.06 ± 3.95 | 8.57 ± 4.43 | 9.42 ± 3.58 |

| Hemoglobin | 10.8 ± 1.89 | 10.97 ± 1.61 | 10.72 ± 2.12 |

| Platelets | 429.9 ± 161 | 422.5 ± 145.2 | 435.4 ± 176.1 |

| ESR | 42.8 ± 27.8 | 34.4 ± 22.9 | 49.5 ± 26.6 |

| Albumin | 30.7 ± 8.9 | 30.4 ± 9.9 | 30.97 ± 8.21 |

| Initial visit | Last follow-up | P value | |

| WBC count | 9.42 ± 3.58 | 8.36 ± 3.4 | 0.1629 |

| Hemoglobin | 10.72 ± 2.12 | 12.4 ± 1.78 | 0.0001 |

| Platelets | 435.4 ± 176.1 | 396.4 ± 132.02 | 0.2485 |

| ESR | 49.5 ± 26.6 | 29.9 ± 26.01 | 0.0009 |

| Albumin | 30.97 ± 8.21 | 33.5 ± 7.97 | 0.1508 |

| Initial visit | Last follow-up | P value | |

| WBC count | 8.57 ± 4.43 | 8.35 ± 3.04 | 0.812 |

| Hemoglobin | 10.97 ± 1.61 | 11.2 ± 2.3 | 0.6344 |

| Platelets | 422.5 ± 145.2 | 388.5 ± 122.5 | 0.3005 |

| ESR | 34.4 ± 22.9 | 33.05 ± 24.4 | 0.8148 |

| Albumin | 30.4 ± 9.9 | 30.55 ± 7.67 | 0.9445 |

Before 1982, Kirsner and shorter observed that inflammatory bowel disease was rare or non existent in Saudi Arabia and Morocco[16]. In 1982 Mokhtar and his group from King Abdul-Aziz University in Jeddah reported the first two cases of Crohn’s disease in Saudi’s[6]. In 1984 Al-Nakib et al in Kuwait reported 14 patients with Crohn’s disease and suggested that inflammatory bowel disease was uncommon in our population was wrong[17]. El Sheik et al from Riyadh Armed Force Hospital reported three cases of Crohn’s disease between 1979 and 1985[18]. In 1990 Hossain and his group from King Khalid University Hospital in Riyadh reported seven cases of Crohn’s disease, three patients were Saudis and the remaining were of different Arab nationalities and concluded that Crohn’s disease did exist among Arabs[7]. Hubler and Isbister from King Faisal Specialist and Research Hospital in Riyadh reported 28 patients with Crohn’s disease between 1976 and 1994[19]. From the previous reports we noticed that Crohn’s disease was present among Saudi nationals in the 1980s but in a few numbers.

The present study was a retrospective study done in a referral, teaching hospital where we noticed an increase in the number of patients with Crohn’s disease over the last a few years (Figure 1).

The total number of patients with Crohn’s disease in KKUH from1983 till 2002 was seventy-seven. Some of them were diagnosed after admission to the hospital for investigation and management of acute problems and the remaining as outpatients for investigations of chronic problems, e.g. diarrhea, abdominal pain and loss of weight.

There was an increase in the number and incidence of patients with Crohn’s disease over the last 10 years in comparison to the first 10 years of the study. This is not definitely related to the accuracy of diagnostic tools because the same investigations were applied to all patients, e.g. colonoscopy and radiological investigations from the start of the study. These may reflect an actual increase in the number of patients since 1993.

The mean annual incidence of the disease over the last 20 years was 0.94:100000 and this is more than that in Japan and some other Far East countries, less than that of Western countries and similar to that in the Province of Granada in Spain[8-13,20].

It appeared that there was a slight female preponderance to the disease and the female to male ratio was 1.33. This is similar to that of North American population and some European countries, while in some studies from various areas of Asia and Europe suggested that there was a marked male preponderance, e.g. 1.6:1-2.2:1 in Japan and Korea respectively and 1.3:1 in Italy[1,8-14].

In many European studies, the age distribution showed a bimodal pattern, with peaks at the ages of 20-29 and 60-69 years[12]. Many other studies, however, have demonstrated a unimodal distribution and some a trimodal distribution[15]. The peak age at diagnosis in our study was between 20 and 30 years and this is similar to the results of other institutions.

The clinical manifestations of Crohn’s disease are variable depending on the involved part of the bowel and the extent of disease. In our center more than two thirds of our patients presented had abdominal pain and diarrhea, half of all our patients had weight loss and tenderness, less than one third had fever and rectal bleeding and a few percent had a palpable mass. These presentations were investigated and the diagnosis of Crohn’s disease was confirmed by endoscopies, biopsies and radiological investigations. The above presentations are the usual manifestations of Crohn’s disease in most of the communities.

The worldwide anatomic distribution of Crohn’s disease ranged from 30%-40% in those with small bowel disease, 40%-55% in those with both small and large intestine involvement and 15%-25% in those with colitis alone[20,21]. In our study the distribution of the disease was different, most of the patients had small and large intestinal involvement and less than a quarter of patients had small bowel disease, while colonic disease alone represented only 6%.

It is difficult to predict which patients with Crohn’s disease will go into remission. Localization of the disease, age, sex or even clinical symptoms did not significantly correlated with outcome of the treatment. Prolonged steroid response could occur in nearly half of patients receiving steroid[22]. In this review, 55 patients (71%) received steroids and 28 of them (51%) went into remission with good response to therapy while the remaining did not, mainly due to poor compliance to treatment. During the long-term follow-up of this study, 42 patients (54.5%) were in remission at any time.

It was estimated that 75% of patients with Crohn’s disease require surgery within the first 20 years after onset or appearance of symptoms. The most common operation performed is a resection of a diseased segment of small intestine and colon[23,24]. Only 12% of our patients had surgeries with resections of parts of their colon and small bowel.

In general, perianal Crohn’s disease is present in as many as 25% of patients and develops in 31% to 94% of patients over the course of their illness. Manifestations of perianal disease include skin involvement (maceration, erosions, skin tags, ulceration, and abscesses), lesions of the anal canal (fissures, ulcers, and stenosis), and fistulae. Approximately two thirds of patients with Crohn’s colitis have perianal fissures.

Unlike ordinary anal fissure, typical fissures associated with Crohn’s disease are multiple, painless, and non-midline in location. Fistulae have been found to develop in 20% to 40% of patients with Crohn’s disease and were difficult to be managed medically[25-27]. More than half of patients with colonic involvement will have anal complications, whereas in less than 20% of patients with small-bowel disease, anal symptoms were likely to develop[28,29]. Only 6% of our patients had perianal disease with fissures, sinuses and fistulae, all of them had involvement solely of the colon.

Patients with Crohn’s disease who went into remission showed significant improvement in their hemoglobin and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) while other laboratory results remained statistically insignificant as that before remission.

Those who remained active showed no changes in all laboratory results.

The epidemiological characteristics of Crohn’s disease among Saudi patients are comparable to those reported from other parts of the world. There is an increase in the incidence of Crohn’s disease in our hospital over the last 10 years. However, the anatomic distribution of the disease is entirely different from other world institutions, with less isolated colonic disease and, all patients with perianal disease have colonic inflammation.

Edited by Wang XL Proofread by Xu FM

| 1. | Loftus EV, Schoenfeld P, Sandborn WJ. The epidemiology and natural history of Crohn's disease in population-based patient cohorts from North America: a systematic review. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:51-60. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Rubin GP, Hungin AP, Kelly PJ, Ling J. Inflammatory bowel disease: epidemiology and management in an English general practice population. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:1553-1559. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Loftus EV, Sandborn WJ. Epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2002;31:1-20. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Loftus EV. A matter of life or death: mortality in Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2002;8:428-429. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Card T, Hubbard R, Logan RF. Mortality in inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based cohort study. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1583-1590. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Mokhtar A, Khan MA. Crohn's disease in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 1982;3:207-208. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Hossain J, Al-Mofleh IA, Laajam MA, Al-Rashed RS, Al-Faleh FZ. Crohn's disease in Arabs. Ann Saudi Med. 1991;11:40-46. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | Yang SK, Loftus EV, Sandborn WJ. Epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease in Asia. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2001;7:260-270. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | Probert CS, Jayanthi V, Mayberry JF. Inflammatory bowel disease in Indian migrants in Fiji. Digestion. 1991;50:82-84. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Munkholm P, Langholz E, Nielsen OH, Kreiner S, Binder V. Incidence and prevalence of Crohn's disease in the county of Copenhagen, 1962-87: a sixfold increase in incidence. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1992;27:609-614. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Löffler A, Glados M. [Data on the epidemiology of Crohn disease in the city of Cologne]. Med Klin (Munich). 1993;88:516-519. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 12. | Martínez-Salmeron JF, Rodrigo M, de Teresa J, Nogueras F, García-Montero M, de Sola C, Salmeron J, Caballero M. Epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease in the Province of Granada, Spain: a retrospective study from 1979 to 1988. Gut. 1993;34:1207-1209. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 13. | Cottone M, Cipolla C, Orlando A, Oliva L, Salerno G, Pagliaro L. Hospital incidence of Crohn's disease in the province of Palermo. A preliminary report. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1989;170:27-28; discussion 50-55. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 14. | Cottone M, Cipolla C, Orlando A, Oliva L, Aiala R, Puleo A. Epidemiology of Crohn's disease in Sicily: a hospital incidence study from 1987 to 1989. "The Sicilian Study Group of Inflammatory Bowel Disease". Eur J Epidemiol. 1991;7:636-640. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 15. | Kaerlev L, Teglbjaerg PS, Sabroe S, Kolstad HA, Ahrens W, Eriksson M, Guénel P, Hardell L, Launoy G, Merler E. Medical risk factors for small-bowel adenocarcinoma with focus on Crohn disease: a European population-based case-control study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2001;36:641-646. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 16. | Kirsner JB, Shorter RG. Recent developments in nonspecific inflammatory bowel disease (second of two parts). N Engl J Med. 1982;306:837-848. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 17. | Al-Nakib B, Radhakrishnan S, Jacob GS, Al-Liddawi H, Al-Ruwaih A. Inflammatory bowel disease in Kuwait. Am J Gastroenterol. 1984;79:191-194. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 18. | El Sheikh MAR, Dip Ven Al Karawi MA, Hamid MA, Yasawy I. Lower gastrointestinal endoscopy. Ann Saudi Med. 1987;7:306-311. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 19. | Isbister WH, Hubler M. Inflammatory bowel disease in Saudi Arabia: presentation and initial management. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;13:1119-1124. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 20. | Moum B, Ekbom A. Epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease--methodological considerations. Dig Liver Dis. 2002;34:364-369. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 21. | Nakahara T, Yao T, Sakurai T, Okada M, Iida M, Fuchigami T, Tanaka K, Okada Y, Sakamoto K, Sata M. [Long-term prognosis of Crohn's disease]. Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 1991;88:1305-1312. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 22. | Munkholm P, Langholz E, Davidsen M, Binder V. Frequency of glucocorticoid resistance and dependency in Crohn's disease. Gut. 1994;35:360-362. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 23. | Becker JM. Surgical therapy for ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1999;28:371-90, viii-ix. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 24. | Iida M, Yao T, Okada M. Long-term follow-up study of Crohn's disease in Japan. The Research Committee of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Japan. J Gastroenterol. 1995;30 Suppl 8:17-19. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 26. | Rubesin SE, Scotiniotis I, Birnbaum BA, Ginsberg GG. Radiologic and endoscopic diagnosis of Crohn's disease. Surg Clin North Am. 2001;81:39-70, viii. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 27. | Thuraisingam A, Leiper K. Medical management of Crohn's disease. Hosp Med. 2003;64:713-718. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 28. | McClane SJ, Rombeau JL. Anorectal Crohn's disease. Surg Clin North Am. 2001;81:169-83, ix. [Cited in This Article: ] |